Darjeeling of the Mind

ALTHOUGH I HAVE been to Darjeeling a countless number of times, when I glimpsed it this time after a gap of so many years, I felt a little breath swell up in my chest.

Our taxi had coughed and spluttered its way up, from the warmth of the valley through which the Teesta flows, winding our way this way and that, holding on to the back of the seats in front lest we tumble backwards inside the car or plunge into our fellow passengers' laps, until we ran into such a thick mist that we couldn't tell if we were inside a fog or a cloud. As our journey progressed, every few minutes a new layer of clothes would appear on our bodies. When I looked backwards, occasionally when the sun permitted, I would see an unmoving cinema-scape of emerald green tea plantations framed in the rear windscreen.

And then there in front of us, shimmering suddenly to light, was Darjeeling. My breath swelled. It was not an exact spot, really. And the town's marketplace was still some way off. There was no signpost which said you had reached or were reaching. For when you are travelling in these parts, you cannot precisely tell which part ends and which new part begins. For all you know, we were already in Darjeeling, just that it wasn't visible.

What lay ahead, a sight I had identified as being of Darjeeling, was a patch of brightness as though someone had flicked a light switch on. It was on a sharp bend in a hill we were gradually approaching. At one end of it was a congregation of tall sombre pine trees, and on the other, a steep fall and a sky of such blue depth that this could only have been the Himalayan foothills. We moved from the mist into this inviting glow, the sun suddenly so warm on our cold faces. It lasted only a minute. The vehicle moved through the bend, circled around the hill, and then we disappeared into another cloud of mist.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

Darjeeling exists as an uncertain landscape in my memory. As a child growing up in the nearby town of Kalimpong, it was a place that was a little too distant to be called home, yet also too close, too filled with relatives and familiar faces, to be described as a holiday spot. It was neither, and in a way, both—a special place that brought the warmth of home and the adventure of a holiday.

Even today, my mind jumps at the speed bump as you descend into town square, where suddenly a quiet town seen from afar sprawls out in front of you, filled with the cacophony of tourists and locals at the motor-stand, the smell of grease and engine coolant mixed with the juniper and cold pine in the air. The roads, whenever it rained, would be littered with small rainbows in little pools of spilt petrol. Darjeeling is not a mere surface that reflects light. It absorbs light, retains it, and reflects something profound. To a traveller—even someone who has visited it as frequently as I have—the whole place seems to hint at some elaborate meaning hidden behind appearances, something only you can interpret. But you can spend a lifetime here and never grasp it.

I was thinking of those memories as our cab made its way through the fog, when the vehicle's lights lit up the silhouette of the Hanuman shrine that rests on another sharp bend. A memory was tickled again. My father stooping in his seat to catch my ear, in a vehicle just like this, so no one else could hear, pointing to the shrine. Hanuman was somewhere mid-air in his massive leap from Lanka to the Himalayas to procure the Sanjeevani herb—my father went on in that grave voice of his—when he was afflicted with a severe stomach ache and made an unscheduled stop, unknown both to mythologists and the devout, except my father and now me. Here, at this unremarkable spot in a distant Indian town, he found relief. He broke wind. All of us, all these thousands of years later—he continued in that self-serious voice—were still living, or in our case travelling, within the fog of his flatulence. The silhouette of the shrine now appeared closer, and in the fog, I could make out the muscular statue of Hanuman, and just for the briefest of moments, a smile on his face.

A Saul Bellow character in Humboldt's Gift, a stand-in no doubt for Chicago's great writer himself, gazing at a sunset on an unremarkable horizon, speaks of how his childhood in the windy city had trained him to make something even of scant settings. "In Chicago you became a connoisseur of the near-nothing," he said. "With a clear eye I looked at a clear scene, I appreciated the red sumac, the white rocks, the rust of the weeds, the wig of green on the bluff over the crossroads." What do you do with the training a place like Darjeeling imparts you with? It is a front row seat to the world's most majestic mountains. The scene is never clear. Everything beautiful is crowding in, the hills, the occasional snowflakes, the people cold in their faces and warm with brandy, defying clarity and description. After this, nothing can ever be as beautiful again.

I opened the curtains of my window. I had checked myself into what could be described as a luxury hotel; everything that gives you more than a bucket of hot water in Darjeeling is luxurious. Outside, a bell pealed, and I discovered a small primary school right beside my window. Things are simple where time is still measured in bells. Dressed in shorts and caps, children lined up in messy rows and gave a rousing performance of their school anthem.

The sun had come out by now.

Until I had left these parts, I did not know many things. I did not know that clothes could dry in a single day, or that the popular coconut hair oil brand, Parachute, is meant to be poured out like any other hair oil, and not spooned out in little scoops of coconut cream. When I first moved to a big city and saw someone pour out the oil on to his palm, I asked him if Parachute had launched a new version of its classic oil.

The cold does many things. It freezes your water pipes on winter mornings. It makes you stand hunched, warming your hands by rubbing them together, just like you would spend a good ten minutes warming your car engine. Only then does your body or car obey your commands. So when the sun finally makes an appearance, however fleetingly, you have to step out and mark your obeisance.

It was the same even now. Sunshine is still a precious commodity. So I stepped out too. It was autumn, the month of October, perhaps the best time to be in Darjeeling. Everywhere, little flowers have emerged among bushes. There is a fragrance of leaf decay in the air. In a few more months, everything will return. People will go back inside their homes, the buds will return to their roots.

Underneath my foot, the land thrummed like an old familiar heartbeat. Everything that people owned seemed to be outdoor—beds, blankets, clothes, vegetables, the people themselves, everything that needed to be aired and dried. People were sitting on wicker chairs that they picked up and shifted every few minutes. They were moving themselves, and their conversations, to catch the warm amber slant of the descending sun. Elsewhere, on a terrace, I saw a washed sweater and right below it a pair of trousers laid out to dry, as though its wearer had been suddenly vaporised.

The most interesting travel stories, I've often felt, aren't the journeys you make to some exotic location faraway. It is those you undertake to a known place, where the landscape might have changed, but your feet recognise the terrain underneath. At such places, both you and the place itself begin to participate in a game of showmanship. It is like the meeting between a son and his long-unmet father. Your purpose, you find out, isn't just to meet your father. It is to show all that you have become, to show all your new possessions and your new life, seeking his acknowledgement and maybe even his envy. But then you realise the place too is showing itself to you. It is showing all you once knew, and all that has been replaced. You can't help then but find a place to sit and consider how far everything disappears in such a short while. Your memories are just that: memories. They have no echo in the real world.

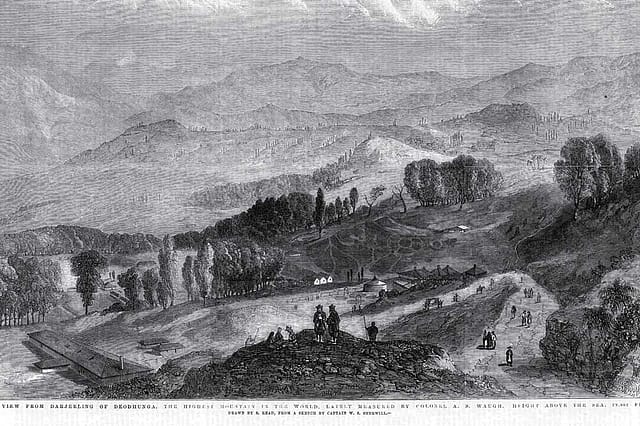

Darjeeling is both a real and imagined place. It is a palimpsest of histories and accents, of people writing their stories over others' to form something new entirely. It was built in the 1800s by British officers as an English home on Indian soil so that they could nurse their homesickness and escape the administrative rigours of the plains. But we often forget there were people already here. And in subsequent years, escaping wars and poverty, more people arrived. And once the British left came their native administrators, people from the Bengali middle-class, who projected another idea upon it, that of the nostalgia of an 'English' hill station.

For the next three days, I spent all my time in town. I did not travel to the popular hill ranges and tea plantations, preferring instead to seek out old haunts of my childhood. I avoided meeting people I had once known, but I noticed I was looking at passing faces to see if I recognised anyone. I went to Keventers and ordered two hot dogs, like I did as a child (when I would tell anyone who cared to listen how I had consumed dog meat) only to discover how salty they were, or how salty they had always been. I moved through the town towards a zone where old cyber cafes used to be located that offered terrible internet speed but hummed with the amorous activities of young couples behind curtains. They had been torn down and replaced by other shops.

Everywhere, armed men marched to and fro, lugubrious, humourless men who never once looked up to the sky and appreciated the sun. At one spot where the road to Darjeeling's most popular spot, the Chowrasta, begins, a man stood upright in an open jeep, with an imposing gun screwed into it, scanning each face, the jeep and gun ready to spring into action any time.

An old familiar play, although with a new cast of characters, had played out here. The town was recovering from a 100-day-long strike for a new state. No new state had been achieved; there was peace now, although visibly feeble. Nearby, a man had died in police custody and everything was beginning to be brought to a standstill. For now there was no sign of it in Darjeeling. People were moving about, rationing their thoughts, whispering to one another.

I visited a spot where a few weeks earlier a crude bomb had been lobbed and another where a man had been shot and dragged, his body leaving a trail of blood through the street. I looked at these spots, but apart from a crater on the road, I couldn't see any trace of these recent events. I found instead a place to sit on the green benches of Chowrasta. A Bengali couple, one of the few tourists in what should otherwise have been a crowded tourist month, approached me. Many years ago, another Bengali couple had approached me and I had behaved insouciantly. The man then, unsure of where he was, had asked me how he could reach Chowrasta. I had pointed to the Mall Road, the road that shoots off from one end of Chowrasta and, circling a picturesque mound, returns to another end of the square. "You see that road," I told him. "You take that road and you just follow it." He took my directions but didn't thank me.

Today, this couple had a less interesting question. They wanted to know where they could find a wine- shop. "Don't you want to know how to reach Chowrasta?" I asked them. They knew where they were, and mumbling something, perhaps a curse, they went to find a more resourceful local.

I moved away. The tourist season was indeed poor. The restaurants were hardly full. At the taxi stand, vehicles stood in a row of mournful silence. You could only see little children, using the vapour of their breaths, to scribble dirty jokes on the windows of these cars. Night would soon fall. Men and women were hurrying themselves home, not wanting to be caught in any violence the darkness could bring.

Through a window in a house nearby, I saw an old couple. They either did not have children, or they, like me, were elsewhere in a less beautiful but more favourable place. They were in their television room. The sound had been turned down and only the pictures flickered on their faces, faces that registered no emotion.

Each man is on a boundless journey. But here in the hills of Darjeeling, you get that feeling you do when you see the ocean spread out before you: a sense that you have reached the end.