The Yogi Law

A few years ago, on an inspection of a police station, a senior police officer asked the inspector-in-charge about his tenure at his posting. "Jabse apni sarkaar hai,'' pat came the answer. The senior officer was left dumbstruck at the lack of inhibition in expressing caste affinity with the Samajwadi Party (SP) government.

Within 15 minutes, a top leader of the then ruling party, called the IG and asked, "Is this the only police station in the entire zone for you to inspect…where the inspector is my caste fellow? Why can't you inspect some other police station?" The senior officer was left on the horns of a dilemma. If he cut short the inspection, the station-in-charge was bound to boast of his prowess and if he did not there would be more friction with political bosses.

A former DGP he consulted advised him to immediately suspend the inspector and make adverse entries in the record of the police station on parameters the station was found wanting. As it turned out, the beat register and one on 'communal' sensitivity were incomplete. Later, both inspector and the senior officer were transferred.

It had become the norm for chief ministers of the SP and Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) regimes to constantly fiddle with law and order. From 1989 to 2017, chief ministers directly decided the postings of SOs, COs and SDMs. "If the posting of inspectors in charge of police stations is to be decided by the top political boss then SSP will have no authority," says former state police chief Vikram Singh.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

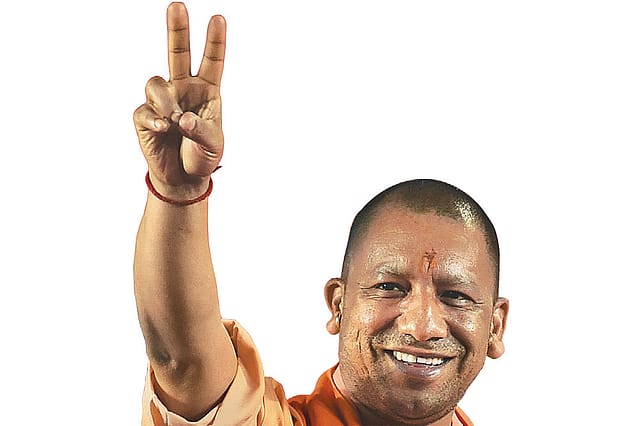

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

The police in Uttar Pradesh (UP) had got used to the norm of "jisake haath mein lagaam, usko salaam (salute those holding the reins of power)''. The sole 'power' of the district SP and SSP was to inspect the parade at police lines and little else. The emergence of Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath was nothing short of a sea change and he began with a policy of zero tolerance of crime. Now, the "thok do (hammer them)" policy has drawn flak. SP leaders object to the language. "Can this be the language of the chief minister?'' they asked. Adityanath's idiom was more than adequate for organised criminals or mafia gangs who long enjoyed political protection. Criminals got the idea that if they did not surrender, or resisted arrest, they were at risk of being shot. "There has been no adverse report on Yogi's lifestyle or about any soft corner for the mafia. The contrast with the previous government that used official machinery for organising cultural shows on their home turfs is obvious," said an officer.

Narrating the ordeal he went through after the death in custody of a terror accused in Barbanki in 2013, Vikram Singh said, "I was in Haridwar to deliver a memorial lecture on Swami Vivekananda. Local journalists mobbed me and told me that a case of murder against me and another officer, Brij Lal (then serving as DG of civil defence), and 40 commandos of STF has been registered. I wondered how I could press a button in Haridwar and kill someone in Barabanki."

There were serial blasts in Lucknow, Varanasi and Faizabad in November 2008 set off by the Pakistan-backed terrorist organisation Indian Mujahideen. The terror accused were soon nabbed by the Special Task Force (STF) of UP Police. Many people had died in the blasts. A terrorist named Khalid Muzahid died due to sun stroke while returning from Faizabad court to Lucknow jail and that led to the cases.

The Allahabad High Court quashed the application of the Akhilesh Yadav government for the withdrawal of cases against the terror accused. The high court sarcastically observed, "Why withdraw cases, honour these persons with Padam Vibhushan, whether they are terrorist or not it's the job of the court not the state government (to decide)''. The then government created such an environment that no police officer from STF or the Anti-Terrorism Squad (ATS) could dare to conduct investigations in terror cases or lodge FIRs.

"The SP government, by accusing us of murder, wanted to send a message to UP police 'How dare you policemen look at the terrorists behind the serial blasts?' The message was clear that we will harass you till your last breath, hold you accountable for your 'sins' against terrorists. After all, the government had already decided to withdraw cases and give financial compensation too," said ex-DGP and BJP Rajya Sabha MP Brij Lal.

The court later quashed the case against both officers. During the 2012 UP Assembly elections, Akhilesh Yadav had promised in his election manifesto that he would withdraw cases against "innocent Muslim youth" allegedly framed in false cases. The court restrained the UP government from taking further action with the contention that the state government alone was not competent to decide and that the accused were booked under a Central law. Therefore, the Centre's consent was necessary. In December 2019, after 12 years of investigation and trial, Additional District Judge Ashok Kumar of the Faizabad court, awarded life imprisonment to two terrorists—Tariq Azmi and Mohammad Akhtar—for the November 2007 blast on the Faizabad district court premises. Tarik Azmi of Azamgarh and Mohammad Akhtar of Ramban, Kashmir, were also handed life sentences in the Lucknow court blast case on August 27, 2018.

Over the last three decades, active political patronage had seen mafia-turned-politicians acquire huge wealth by forcibly occupying Gram Samaj land (belonging to the village council), property listed as belonging to "enemy and/or evacuees", Waqf property and the land of the poor. They indulged in illegal cattle trade, including illegal slaughter and smuggling to Bangladesh via Bihar and West Bengal with impunity. According to Brij Lal, there is a long list of criminals promoted by SP's Mulayam Singh since 1989 when the party first assumed office. They include names like Arun Shukla, DP Yadav of Ghaziabad, Kamlesh Pathak of Etawah (currently in jail), Madan Bhaiyya of Meerut, Atique Ahmed of Prayagraj, Mukhtar Ansari and his elder brother Afzal Ansari (currently BSP MP from Ghazipur), Ramakant Yadav and Umakant Yadav, Baleshwar Yadav and Om Prakash Paswan of Gorakhpur, and so on.

Yogi Adityanath has also attacked the 'Left ecosystem' that has promoted the concept of the 'Ganga–Jamuni Tehzeeb' as a political concept. The narrative was created to accommodate leaders of the Mulsim League who stayed back in India after Partition in 1947. Venkat Dhulipala's book, Creating a New Medina: State Power, Islam, and the Quest for Pakistan in Late Colonial North India, details how nawabs and zamindars like the Raja of Mahmudabad worked for the creation of Pakistan.

APPEASEMENT, CORRUPTION AND NEPOTISM were the three pillars that characterised governments led by the caste-based regional parties that ruled UP. "The communal violence Bill proposed by the Manmohan Singh government was a classic case of appeasement. Had the Bill been passed by Parliament, Hindus would have been reduced to second-class citizens. No FIR, no raid could be conducted in certain areas. All in the name of protecting minorities while actually harming everyone's interests," says Vikram Singh.

Extortion was common if you bought an expensive vehicle, property or if news spread of an impending marriage in a rich family. There would be a call from the mafia backed by the ruling party that a particular sum would need to be paid. In Lucknow, in the posh area of Hazratganj, it was not uncommon for youth to drink in cars and make lewd comments at women in marketplaces. Such scenes were common enough. Eve teasing acquired epidemic proportion in Lucknow.

Fake papers were prepared in collusion with the employees of the sub-registrar office and the mafia targeted prime properties. They contacted their victims with humility. In Allahabad, the mafia illegally occupied land worth Rs10 crore for just Rs51 lakh. The landowner was informed that the ganglord's son wanted to set up a nursing home and any monetary value of the land had meaning only if you lived to enjoy it.

The DM of Ghazipur used to play badminton with Mukhtar Ansari in Ghazipur district jail. Mukhtar had a pond in the jail for farming fish. Mukhtar Ansari, Shahbuddin and Atiq Ahmed were all suspected of anti-national activities.

How Mukhtar Ansari managed to get himself transferred to a Punjab jail is explained by a fake case being registered against Rocket and Dimpy, two members of his gang. What was the compulsion of the Congress-led Punjab government to protect Mukhtar Ansari and prevent his transfer to UP is a puzzle. Shailendra Pratap Singh, a DSP, had seized an LMG that was to be supplied to Mukhtar Ansari. He was pressured to drop the POTA charges and remove the LMG seizure and was persecuted to such an extent that he resigned. The SP government evidently had surrendered to mafia gangs.

SP leader Azam Khan boasted that the PAC (Provincial Armed Constabulary) never entered "hamara ilaka (our areas)". Not many officers were ready to refuse illegal orders. Political scientist AK Verma, director of the Centre for the Study of Society and Politics, Kanpur, contends that veteran Congress leader Kamlapati Tripathi had, in 1971, first expressed concern about the entry and assimilation of criminals in politics. Verma says the last 50-year period could be broadly divided into three phases—criminalisation of politics, politicisation of criminals and the "mafia-isation" of politics. For all those who matter in the polity there was a close nexus with criminals that stretched into the Mumbai film world too.

According to Verma, Yogi Adityanath is the first chief minister, in any state, to launch such an aggressive campaign against organised crime: "This is Yogi Adityanath's brand of disruptionist politics. He is the first chief minister to have caught the mafia bull by its horns. The anti-mafia campaign will reclaim lost territory for the state and is a huge step towards cleaning up politics." He adds, "Yogi Adityanath is doing what a welfare state is required to do. Earlier there was welfare only for criminals. It's for the first time that the government is actually working for the welfare of the common people." He posits the chief minister's deliberately showcased policy of war on the mafia and organised crime against the larger public demand for a clean politics. "We need a nationwide campaign along the same lines to uproot the influence of organised crime in society, taking off from Adityanath's own campaign. The battle should not be confined to UP alone. The campaign would bring spectacular results if it were to be launched in all big states," he says.

The UP government targeted criminals to begin with. Had politicians been made targets first, there would have been accusations of vendetta politics. As the mafia gangs were neutralised and their ill-gotten wealth seized, their commercial buildings taken over and demolished, the other two groups in the chain—the politicians and the police—would automatically fall in line. Persisting with the old ways would mean being unceremoniously ousted, with stringent penalties.

Spelling out the difference between SP and BSP candidates, in this context, one political observer maintains that BSP candidates were drawn from the local elite of all castes and they depend on the Dalit vote bank, making it easy for party supremo Mayawati to exercise control over them. But in the case of SP, the district leaders were like local warlords with deep pockets and they also controlled the local party machinery. Thus, they were less vulnerable to the party's disciplinary whip. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), though, has had a different system of operating locally. Some call it a hybrid of SP and BSP systems. Yet, the organisation of BJP, backed by the secretary (organisation) of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), held some sway over party legislators and other divisional leaders.

A senior IPS officer said that when he joined the service, a police inspector had told him "You have to choose between law and the order of the day according to political bosses. Now, I am of the firm view that you need to have law and order according to the rulebook."

The Mukhtar Ansari gang was behind the attack on Yogi Adityanath, then MP from Gorakhpur, during the communal riots at Mau in 2005. Ansari was then MLA from Mau. Adityanath has drawn a leaf from Kalyan Singh's approach to policing when the late saffron stalwart became chief minister in 1991 and for the first time mafia-politicians began to face the heat. Having got a full five-year term, he had made crime fighting a key feature of governance.