The Heroes of Colachel

The forgotten battle of Travancore against colonialism

/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/HeroesofColachel1.jpg)

Eustachius de Lannoys surrender to Marthanda Varma at the Battle of Colachel

CERTAIN HISTORICAL INCIDENTS are destined to become footnotes while others remain centrestage and dominate public discourse. Plassey, now called Palashi, in West Bengal, continues to symbolise the start of English military and political power in India thanks to the defeat by the British East India Company on June 23, 1757, of the Nawab of Bengal, Siraj ud-Daulah, and his French allies. But it was at Arcot in southern India in 1751 that the British first successfully tasted victory for their divide-and-rule policy. Plassey came later, although the man behind both victories was Robert Clive, a soldier of fortune who went on to become the first British Governor of the Bengal Presidency.

Similarly, on a global scale, Japan walks away with the credit as the ‘first’ Asian power to defeat a European force in late medieval and modern history thanks to its triumph over the Russian Empire, then ruled by Czar Nicholas II, in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05.

But long before the Japanese accomplished such a feat, as early as 1741, the kingdom of Travancore, spread over tiny areas of present-day south Kerala and southern Tamil Nadu, had won a battle against the Dutch East India Company in a place called Colachel (of erstwhile Travancore), which now falls in the Kanyakumari district of Tamil Nadu. While history textbooks taught in universities in Kerala and chronicles of the time in Malayalam have dwelt at length on this piece of history, the incident has not grabbed much space nationally. Some books by modern Kerala historians have attempted a blow-by-blow account of this war, and they hasten to term it a David vs Goliath one. Yet, in the larger scheme of things, unfortunately, Colachel rarely finds mention outside of Kerala or southern India. Notably, this is nothing new or rare. Modern reformers of the stature of Sree Narayana Guru, arguably the most successful reformer in the country, are rarely discussed outside of Kerala although their personalities and advocacies perhaps far excel those reformers who have become household names and found a place in the pantheon of Indian legends.

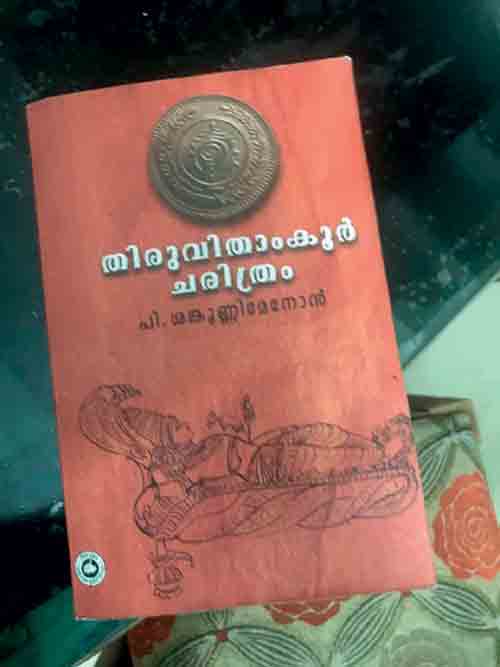

The widely read book titled Thiruvithamkoor Charithram (History of Travancore), authored by P Shankunni Menon, offers exhaustive accounts of the war between Maharaja Marthanda Varma of Travancore and the Dutch (who are referred to as lanthakkaar, a word that can be loosely translated from Malayalam as men of Lantha). Similarly, in Malayalam, the Portuguese who had come earlier and were trounced in several trade ports along the Malabar coast by the Dutch were called parankikal (paranki men).

Travancore back then was a geographically minuscule area comprising Venad, Jayasimhanad, and Odanad principalities in southern India, and yet it was a stumbling block for the Dutch East India Company’s trade interests in the region. Tensions between King Varma (1706-58) and the Dutch resulted in the Travancore-Dutch War that started with clashes in 1739 and culminated in the Battle of Colachel. It was then that the state of Travancore began to expand and became a larger kingdom encompassing what is today the entire southern Kerala and parts of southern Tamil Nadu, including Kanniyakumari and parts of Tenkasi. The likes of historian MO Koshy provide (Dutch Power in Kerala; 1989) several insights into the Dutch designs in southern India and the huge setback these Europeans suffered following the Colachel war, notwithstanding the support certain neighbouring principalities had offered the Dutch for fear of Marthanda Varma’s expansionist policies.

Noted Kerala-based historian and author Rajan Gurukkal disapproves of the narrative gaining momentum lately that the Battle of Colachel isn’t highlighted enough in history textbooks, and he is right about it if you consider pages devoted to the event in Malayalam history books. He reels out names of books such as the one by Koshy and others in English, too, including Rise of Travancore: A Study of the Life and Times of Martanda Varma by AP Ibrahim Kunju. Incidentally, the Maharaja’s name and Colachel secure innumerable references in essays and even literature, local historians point out, backing Gurukkal’s view. “At least, I can safely say there has been no purposeful suppression of the historical importance of Colachel and the victory against the Dutch,” points out Gurukkal. He also places stress on Marthanda Varma’s abilities to organise his people and to ensure that there were no local allies from within his principality who dared turn against him and join hands with the Dutch. “No alien contingent fully devoid of any local support can exact victories,” he states.

The book, Thiruvithamkoor Charithram (History of Travancore), by P Shankunni Menon, offers exhaustive accounts of the war between Marthanda Varma of Travancore and the Dutch (who are referred to as lanthakkaar, a word that can be loosely translated from Malayalam as men of Lantha)

For his part, P Shankunni Menon, that great chronicler of the region’s history, provides readers with a comprehensive analysis of how the war was fought and won, starting from random clashes between Travancore and the Dutch forces years preceding the final victory that forced the Dutch into abandoning troubling Travancore again. He then goes on to explain how the Dutch Navy from Ceylon (Sri Lanka) began assaulting villages, going on a rampage of destruction in 1741 before occupying areas from Colachel to Kottar, a locality now in the Nagercoil district of Tamil Nadu. The Dutch were then expected to attack Padmanabhapuram, the capital of Travancore. The king, on receiving the news of the Dutch aggression, ordered his forces, then comprising mostly Nair soldiers, to be prepared for war and asked his top official and lieutenant Ramayyan, who at the time was busy with battles in the northern parts of the kingdom, to immediately return along with his forces. Ramayyan (1713-56), popularly known as Ramayyan Dalawa, was instrumental in the consolidation and expansion of Travancore at the behest of Marthanda Varma, the king who is feted as the creator of modern Travancore. The victory over the Dutch forces was pivotal to that consolidation and expansion, although it is historically significant for other reasons, too, including the fact that it is a burnished chapter of military history, of an Asian military success over the technologically superior Europeans of the time. Again, the Colachel loss came in as a nightmare of the Dutch dream of conquest in the Indian subcontinent.

When the Dutch forces occupied areas under Travancore in 1741, Marthanda Varma dispatched strongly worded mails to the Dutch governor of the time stationed in Kochi and sought help from the French forces in Pondicherry—he also offered rewards to the French in return for their potential assistance in neutralising the Dutch. He sent a delegation to impress upon the French. The French agreed to the terms, although the war was finally won by Travancore largely on its own, according to most historical accounts. On August 10, Travancore forces led by Ramayyan surrounded the Dutch forces and launched a fierce attack, prompting the European rival to agree to surrender on the condition that they would be allowed to flee with their weapons, as Koshy explains. Marthanda Varma, however, wanted the Dutch to surrender and face imprisonment. Travancore’s soldiers confiscated a huge cache of arms, including 389 guns. One of the prisoners, Eustachius Benedictus de Lannoy, a French-born Dutch military strategist of Belgian descent who had worked for the Dutch East India Company in Ceylon, later became admiral under Varma and continued to serve Travancore until he died in 1777.

Shankunni Menon, as well as many other historians, says that it was Lannoy who brought European standards of military discipline to the Travancore army in a phase that saw the kingdom expand at a fast clip, which at its peak had a large part of today’s Kerala in its fold. Professor PK Michael Tharakan, a senior academic whose areas of specialisation include economic history, tells Open that the idea of a centralised army was, until then, new to Travancore. “It was following the Colachel victory that Travancore had a centralised army and a centralised state,” he avers. Tharakan, a highly respected historian who is the current chairman of the Kerala Council for Historical Research, says that coastal areas of India were vulnerable to attacks because, in sharp contrast to Europeans, India didn’t have comparable technology to launch attacks on the sea against warring navies and engage in a war with them at sea, until very late. He notes that unlike Prince Henry the Navigator of Portugal, who had set up schools to aid maritime expansion and colonisation, and other European figures, India of the time—in the 14th and 15th centuries—didn’t have naval forces until Shivaji and others on the west coast came up with the idea of building a naval force in the late-17th century. Technological innovations in Europe also meant that they could carry cannons on the deck of their ships besides other weapons, revolutionising maritime travel. According to Tharakan, it was only later that the kings of Bijapur and Ahmednagar built their navies. While Kanhoji Angre was the chief of the Maratha navy, Kunjali Marakkar was the title of the head of the naval forces of the king of Calicut (today’s Kozhikode), Zamorin. He recalls that the Europeans had developed their naval technologies centuries before them.

The Battle of Colachel was also significant in ushering in centralisation in agriculture and trade in Travancore, Tharakan points out. It was following this war that Travancore had a marching army along the lines of the Europeans, he says, adding that the Dutch commanders found it easier to teach the people of the then Kerala to march by tying cloth on one leg and a coconut palm leaf on the other and instead of left, right, they used to say a more intelligible chant—“ola [palm leaf] kaal, sheela [cloth] kaal”—so that the troops marched ahead in rhythmic cadence.

The noted academic says that Marthanda Varma, who soon entered into treaties with foreign powers, also centralised trade by bringing in 160 items under the monopoly of the state, although local traders continued to have their sway. In a centralised Travancore, he observes, many communities that didn’t have much significance in the scheme of power earlier, found opportunities to trade and make cash, notably Syrian Christians, Muslims, and the Ezhava community. As a result of their growing wealth, they started demanding more say in power, triggering social change. These neo-feudal forces, he says, no longer wanted to play second fiddle to the dominant communities of the time, who were mostly from the upper sections of the Hindu hierarchy. Soon, such aspirations led to what he calls socio-ritualistic reform movements, which some others describe as the Kerala Renaissance. Tharakan uses the expression, socio-ritualistic reforms because they entailed getting rid of rituals seen as lowly and embracing those that were seen as superior. For instance, he explains, worship among Ezhavas involved gods and goddesses who were into black magic and so on, and Sree Narayana Guru, who was the foremost reformer of the late-19th and early 20th centuries, inspired people to switch to worshipping gods and goddesses acceptable to the upper classes. The rich in each community that had won economic freedom through trade among these formerly less powerful classes backed the reformers, resulting in overall horizontal reforms. Except in the case of the most backward classes, this trend proved to be true.

Professor Tharakan states that monopoly in trade continued in erstwhile Travancore until the early 1920s, although the calls for getting rid of it had started off much earlier in Europe with economists such as Adam Smith leading from the front in the 18th century, calling for an end to monopolistic practices in trade.

Interestingly, several new snippets of history related to the Colachel war keep surfacing, some of which are based on anecdotes and oral histories. It is said that the role of the fishermen, who were low in the caste hierarchy of the time and had no role to play in the army and had an inconsequential presence in society but chose not to join the Dutch, notwithstanding repeated entreaties by the Europeans, was crucial in Varma’s victory. It is also said that Lannoy hired them in the new army he helped build. Meanwhile, there are also claims that Travancore had received support from European foes of the Dutch in its triumphant war.

Whatever that is, the royal family of Travancore wasn’t among the most iconoclastic of our royals when it came to getting rid of untouchability. It required movements and social upheavals for them to change policies and ensure jobs for those previously classified as untouchables. But it looks like, as Professor Tharakan suggests, Colachel was a force multiplier of sorts, perhaps in an unintentional sense.

About The Author

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Crashcause.jpg)

More Columns

Bihar: On the Road to Progress Open Avenues

The Bihar Model: Balancing Governance, Growth and Inclusion Open Avenues

Caution: Contents May Be Delicious V Shoba