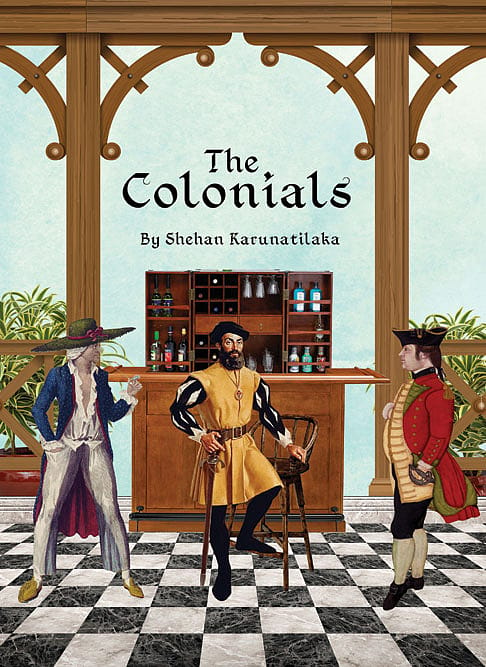

The Colonials

An Englishman, a Dutchman and a Portuguese man walked into a bar. They ordered two arracks and a beer, and sat at the end of a terrace, far from everyone who was yet to arrive.

The bar was at The Galle Face Hotel, constructed in 1861, not that long before this meeting took place. The terrace overlooked the Indian Ocean as it does today, and was uncrowded, save for these three, dressed in the garb of merchants and smiling as widely as those who do not trust the other are wont to.

"Tavern looks agreeable," remarked the Dutchman, surveying the bottles of rum hanging from the counter. "In the hill country we have pleasant taverns, but none as decorated."

It was two in the afternoon, a good three hours before the hotel guests, the colonials and the native elites, came down to watch the sun set on empires.

"We could've met at the club," said the Englishman. "I even suggested it to Fonseka."

"Not a good idea," said the man from Portugal. "Your face is known at Club. And mine too, I fear."

"Edgar Walker," said the Englishman, extending his hand. "Bank of England. Pleased to make your acquaintance."

"Pieter van Cuylenburg," replied the Dutchman. "VC Plantations. A pleasure."

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

"Patience please gentlemen. I will introduce you appropriately when drinks arrive," said the Portuguese. "They say this place has the best waiters in Ceylon."

"So we'll get our drinks in 45 minutes then?" said Walker and they all laughed.

The floor was chequered like a chessboard and descended in ledges onto a lawn with palm trees. The sun sat behind a cloud and the sea sang to the crows on the parapet. Behind the bar, Queen Victoria looked out from a painting, above an insignia with a lion and a unicorn fighting over her. The Englishman sat with his back to the painting.

"I will judge you not, Van Cuylenburg. Though you swill the local beer. Forgive me, but the stuff is beastly."

The Dutchman grinned, "I have a taste for native delights." His eyes twinkle. "As have you, I believe."

The Englishman sparked a beedi the size of a cigar.

"I have grown accustomed to the arrack" said Edgar Walker. "It is whisky mixed with rum and is unpalatable straight. Though it has a subtlety when combined with citrus."

"A fine description sir," said Lorenzo Fonseka from Portugal.

"As long as it doesn't taste like the so-called sweets they served me at the estate… " said Pieter making the face of a revolted child.

"My servant gave me local plum wine," said Lorenzo. "It was like Pinot from Naples… "

"Surely you jest?" said Walker.

"… had been served to a cow… whose piss I was consuming."

They all laughed and the drinks arrived and the waiter poured and grinned, despite not hearing the joke.

"Pray tell. Señor Lozenzo, are you still seafaring these days?"

"Indeed. But the oceans have grown savage. Pirates hit my fleet near Java. Though nothing was stolen."

"Remarkable! How so?"

"It is wise to have a bigger cutlass than the pirate."

There was less laughter this time and the Englishman puffed on his beedi and Lorenzo Fonseka gulped his arrack sour like a sea monster swallowing a ship.

"Now let us do this properly gentlemen. Sir Edgar Wallace, I introduce you to Pieter van Cuylenburg, the finest planter of the Dutch East India Company."

"Hang on old chap. Ole Queenie hasn't knighted me yet."

The Dutchman signalled for another beer. He had been preparing his speech all week and had forgotten the first line. He fidgeted with his coat and wondered whether taking it off would be disrespectful. The capital was hot and muggy, unlike the cool hills to which he was accustomed.

"Surely Sir, it is but a matter of time before Her Majesty… "

He glanced at the portrait of Victoria and the barman below it. The Englishman made a gesture with his hand that said thank you, enough and let us move on.

"I am honoured that you granted me this audience sir," says Van Cuylenberg.

"Edgar Walker has served as governor of the Bank of England in Siam, Kowloon and now Ceylon."

"I am aware of Sir Edgar's reputation."

"And yet I am unaware of yours," said the yet-to-be-knighted banker.

Lorenzo sprayed lemonade into another glass of arrack. He had learnt to drink it while running spices from Kerala to Kampuchea, long before he owned a fleet and dared to invest in cutlasses.

"Pieter van Cuylenburg owns the finest estate south of Hatton."

"Tea?"

"Not quite Sir."

"Coconut?"

"Perhaps Pieter will explain."

The Dutchman shuffled on the mahogany seat, took off his gloves and then began.

They say that wind brought the Portuguese, and greed brought the Dutch. Fear is what brought me to Ceylon twenty years ago. My father was a man of power in Rotterdam, he ran the breweries for Adriaan Heineken. But the cult of that heathen Marx reached our factories and my father became a union man, and a friend of the Sicilians. By the time I was 15, he was smothered in lawsuits and stifled by debt. I tell you this, so you know that I am not a silver-spooned nobleman, merely an honest toiler of some diligence.

On my 18th birthday, I was visited upon by seven Sicilians who told me that as his only heir, I would inherit my father's dues and should he not survive the debtor's prison, the burden would be mine to settle.

Before that month had expired, my mother's uncle had procured me a job with the Dutch East India Company and I was aboard the Batavia, bound for Port Louis, Goa, Ceylon and Singapore, stealing away like that proverbial night thief.

Unlike Señor Lorenzo, I am no sailor, and the journey made me bring up bile, and from my sickbed I cursed the ocean, my father and my creator. I arrived at these coconut shores one sunrise after a terrifying storm and knew on first sight that Ceylon would be my home. Years later, when I set eyes on those hills behind Mawanella, I knew that departing these shores was no longer a possibility.

I joined the Plantations Division of the East India Company and served my apprenticeship in Badulla and Ella amidst teascapes that mirrored my visions of heaven. Where not long before, Dutchmen like myself had planted coffee and parted with fortunes. For by 1870, a dastardly leaf disease had wiped out every coffee plantation in these fair hills, and turned princes to paupers.

I rose up the ranks at a steady pace and was managing four estates by the time I was 30. I paid all debts to my father's swarthy creditors and won him his freedom though he expressed paltry gratitude. Thus, with some indignance and much relief, I settled into my planting life.

I savoured the sunsets in the hills, the meals at the club and the evenings with dusky maidens. I gambled seldom and fell to the amber nectar hardly, and so saved most of my generous stipend. And then I made the folly that has ruined many free men and will continue to ruin more for as long as skies are blue. I took myself a wife.

No, not among the dusky maidens of the tea fields. Perish the notion. Having endured my father's disgrace, scandal is a plague I can no longer tolerate. I procured myself a respectable bride from my mother's village of Giethoorn. Up till then, I had considered myself a moderate success in life and had been pleased with my humble accomplishments.

Up till the moment I brought Geertje from Gierthoorn to the Maskeliya hills.

Geertje did not approve of my manners or my quarters or the planter's club or how familiar I was with the servants or that I was beholden to the Company.

"A true gentleman manages his own lands," she said, while dragging rakes over my lawns and brooms across my floors and planting her complaints between my ears.

Over the next forty-eight months, she had extracted three children from my loins and persuaded me to pour every shilling I had into the magic soil behind the hills of Mawanella, where, on the advice of my darling wife, I grew not tea nor cinnamon nor coconut nor rubber. No gentlemen, I grew the crop that had suffered that ignoble death on these very hills a few decades previous. I grew coffee.

Geertje bore me two daughters and a son, but mostly proved a matriarch to the coolies who worked on our plantation. While forbidding me familiarity with the help, she would sit on the floor with the kitchen staff and gobble rice and curry and gossip, listening to the ailments of the womenfolk, while ordering the men to do repairs around the house. While I spent the monsoon season galloping across 50 acres on my Kashmiri steed, trying to convince the traders in Kandy that Ceylon coffee was making a comeback.

One man in particular, my head gardener Thiranjeevan, had wormed his way into my wife's trust. A rodent of a fellow, he dabbled in crude sorcery and made luck charms for the natives. Every cursed day, he would read my wife's horoscope and instruct her on auspicious times and how to avoid the evil eye. Without my knowledge, he planted charms along my perimeter allegedly to bless my crop and ward off evil. Furious, I demanded he remove each one and he complied like a petulant child, though I suspected that he replaced them with curses.

Gentlemen, I did not like the influence this coolie brought to my good Christian household, and while I laid in the arms of my plantation concubine, I plotted on ways to be rid of this pestilence. And then against all logic and science, his charms began to work. Ceylon Coffee outsold Lipton Tea for two years in a row, our returns tripled, and my wife's melancholia evaporated.

I had spies watching Thiranjeevan, lest he attempt to inveigle his way into my wife's bedroom. But when talk emerged of him building a shrine next to our bungalow, matters had to be escalated. I instructed three of my concubines to accuse him of lewd behaviour and unwanted affections, though these ripples and rumours failed to elicit the scandal I required. When the estates' earnings went missing from the main office and were found under Thiranjeevan's bed, I had all I needed to be rid of the menace.

My wife was inconsolable and barked at me for weeks. Gentlemen, I should've foreseen what followed but so relieved was I to be rid of this vermin that my good judgement was suspended.

A week after I dismissed him, the heavens imploded. Two of my children got the pox, spots appeared on my coffee leaves, my workers began complaining of strange noises at night, and the Disawa of Kandy, who had loaned me half the acreage of the estate, informed me that he was calling in his debt before next month's Vesak festival.

My wife is taking the children to Gierthoorn and I am left with a cursed estate, angry workers and a debt I cannot pay. I was engaged in a cost-benefit analysis on the pros and cons of throwing myself off those cursed hills before Señor Lorenzo agreed to hear my woes. He consoled me and presented me with a solution that could save my estate and make one fortuitous investor very wealthy.

I present this plan to you Sir Edgar, despite my initial misgivings. I am but a humble planter, unversed in the letters of the law. But I do know that if done with legitimacy, even a criminal act can cease to be viewed that way, especially when done out of view.

A FEW MORE patrons had arrived at the Galle Face Terrace. A rotund man in a plain suit was sitting with a fetching lass in a palm tree's shadow. He glanced around several times before taking a seat with his back to the room.

"That's Tommy Maitland. What in Hades is he wearing?" Edgar Walker was on his second arrack and third beedi. He nodded at Van Cuylenburg who looked relieved to have finished his plea.

"That is Sir Thomas?" asked Lorenzo Fonseka, glancing at the girl arching her back and stroking her long black hair.

"That must be the dancer. Her name is Lovina. My wife is an incorrigible gossip. Apparently, old Tommy is quite smitten."

"That will end badly," said Van Cuylenburg, folding his arms.

To their right was a view of Galle Face Green, where horses used to race twice a year. A few local children were flying kites and chasing each other across its patchy grass.

"I have seen Pieter's land. He should thank his fine wife for making him buy it. It is of soil that I have never seen on any of my voyages," said Fonseka. "The dirt is cool and moist and the colour of cocoa and oak. It will nurture any seed that falls upon it."

"And yet my coffee leaves look like a leper's face."

"Patience Pieter. I will find men. We will dig up these curses. We will deal with your witch doctor man. I too have encountered the native magic, it is not something to be sneered at. He is still in the village?"

Van Cuylenburg nodded.

"Then that is the easiest part of your issue. Once we have unearthed every piece of sorcery, we will plant again. But not coffee. That was your wife's one foolishness. We will quadruple your investment by planting something else."

It was all part of an act and Lorenzo was a natural actor. A group of locals arrived at the bar, wearing finer clothing than anyone present. Their faces betrayed a diffidence and uncertainty that they carried with them into the room. They examined the menu, took glances at the wealthy foreigners and slunk off towards the lobby.

"If the locals unite, they will be unstoppable," said Edgar Walker. "But that will not happen in our lifetimes."

"Their army is weaker than their beer," said the Dutchman taking a sip, but this time none of them laughed.

"I am perplexed Señor Lorenzo," said Walker. "Are you suggesting I invest with the Bank of England or privately?"

"The investment I am about to suggest cannot go through your country's bank."

"Splendid," said Walker. "As long as we're clear."

SIR EDGAR, you know me as a pirate. Let us not mince words. The oceans are vast and filled with monsters and that is where I have plied my trade these many years. Thankfully I have made more friends than enemies, and if I have a talent, it is knowing which cargo to carry and which to conceal.

The sea has taught me everything. You do not need to believe in ghosts to fear them. I started taking spices up and down the silk route, before the waves got crowded with scoundrels and racketeers. I could not run my fleet at the mercies of Lisbon or London or Amsterdam and the prices they set.

For there was only one industry that I could see growing from Kampuchea to Indochina to Manila to Ceylon. The industry of war. Cutlasses, armaments, bullets. The demand was constant, the price was agreeable. It is a treacherous business, but if not me, some Dutchman or Englishman or, worse, some Indian or Chinaman will take my place with glee.

Because of my many friends and my few enemies, I now have transport across the country and in useful places across the orient. Among my clients I have kings and kingpins, so my shipments receive safe passage from anywhere to anywhere. I have spoken already to the disawa of the Kandyan kingdom and I believe he will accept the terms we present.

But once we have dug up the land and expunged all curses, we remain with the conundrum of what to grow. Forget coffee, Pieter. This is not 1848. Forget tea, that ship has long sailed. Instead, I present you with a crop that is easier than tobacco to grow and harvest and is twice as lucrative. A crop that is in demand across the indies and the orient and even closer to all our homes.

It is consumed by gurus and rishis across India, by the Gurkha and Malay soldiers and their fiery wives, it is prescribed by doctors in the far east and even enjoyed in this very city. I have inquired at this establishment and they have granted me permission to do what I wish to. Sir Edgar, may I trouble you for a light?

"PUT THAT away man!" snapped Edgar Walker in a hiss that made Van Cuylenburg jump. "Tommy Maitland is there with his whore. And you mean to make a spectacle of us?"

Lorenzo shrugged and passed the pipe to Pieter who furrowed his brow in confusion. Did he puff on it and complete the pitch, and offend the investor?

"The smoking of hashish is not against the law sir. Neither is the cultivating of hemp. It is as natural as the tobacco leaf, though not as bewitching or destructive."

"I… I take issue with the word bewitch. This juniper smoke enchants and calms like no other. But it does not enslave the senses."

Pieter delivers his line and Lorenzo nods with approval.

The children on the green abandoned their kites for cricket bats as more members of the local elite occupied the bar to light their cigars. No one paid heed to the table at the corner of the terrace or the smoke from an ornately curved pipe as it curled upwards to be sucked up by a fan.

"Many believe ganja to be a civilising agent. This very hotel has a private menu for guests. I am told that Anton Chekov stayed here with two mistresses and ordered pipes of Afghan cream and king coconut on the hour. Andrew Carnegie stopped here to meet investors from Shanghai. And he left Lanka with a disdain for its entrepreneurs but an appreciation of its sweet green leaf. And it is not to tea that I refer," Lorenzo Fonseka smiled and passed the pipe to the Dutchman.

Edgar Walker lit two beedis, puffed on one and let the other smoulder in the ashtray, a foul-smelling incense to mask the musky scent of the devil's weed.

"I am pleased to see that you have thought this through," he says shaking his head. "But I am neither coolie nor reprobate. I am a businessman."

"This was growing wild on my estate sir… " Van Cuylenburg places the pipe by the ashtray. "If I fill my acreage with it, it will deliver a margin of profit four or five times that of tea."

Edgar Walker put on a pair of black leather gloves and handled the pipe as if it were the tail of a scorpion. He took one puff on it and raised an eyebrow. Then he returned it to Lorenzo and went back to his beedi.

"It is the finest I have tasted. But they say a rat dressed in Saville Row tweed is still a rat."

"Sir, I do not follow."

Walker took a look at the natives at the bar and shook his head.

"Those two at the bar are local surgeons. I considered taking my wife's sister to one of them for her goitre.

Don't look now man. But the stocky one was educated in Cambridge and his father owns rubber factories along the coast. In the end, I waited until they sent me a house surgeon from Sheffield."

Lorenzo took another puff. The discussion was not proceeding as he anticipated, but the Mawanella smoke was too exquisite to waste, and the afternoon sky too pretty to ignore. If this British toff wished to climb on his horse, Lorenzo would walk and it would be Britannia's loss.

"The locals may one day run this country for sport. And they will run it into the ground. I will not let one of them take a knife to a relative of mine, even one whom I despise as much as my sister-in-law, no matter which school their daddy sent them to. Van Cuylenburg, your misfortune is not your wife's fault. It is yours. Never let the locals beyond your veranda."

Lorenzo shook his head.

"Forgive me, sir. But these thoughts belong to another century," he says. "We have all had our way with this island. Maybe it is the turn of the locals now."

This got the biggest laugh of them all.

Edgar ordered a last round of drinks and the bill. "I had hoped the Chinese or the Indians would step up and take this burden off our hands. But the Chinese are gamblers and the Indians are drunks. We remain Ceylon's only hope."

Van Cuylernburg had abandoned his beer. He poured the arrack from the bottle and topped it with ice. His hand shook.

"I too was sceptical, Sir Edgar. A Dutchman growing hemp is as hackneyed as a Dutchman who flies. But the figures cannot be ignored."

"You probably think me to be a man of prejudice. But it is not me that is a racist, it is mother nature. She is the bigot. It is she who endowed the European races with intellect and spirit, while leaving the lush lands to the simpler browner tribes."

"I take it you are not interested in our proposition."

"On the contrary, I am interested in visiting this Eden in the hills. But I will not invest in marijuana. It is beneath me and more importantly, it is beneath my profit measure."

The Portuguese and the Dutchman exchanged a glance.

"But what I do have, gentlemen, is a counter proposal."

I DO NOT wish to bore you gentlemen with my biography. Suffice to say I benefitted from that lottery of birth that made me an Englishman born to a family of means. You both may believe in God and destiny but I know both to be imposters. I occupy the space I am in through astute decisions and benevolent fortune.

But firstly, may I ascertain this much. Lorenzo Fonseka, you have a secure route from here to Shanghai, Beijing and Taiwan? I do not mean channels like those malaria-infested canals that the Dutch run spices through, no offence Pieter.

Good. I will rely upon the great Portuguese mariner's repute. I can make sure you remain untroubled by authorities as far as Singapore, but after that your risk is your own.

I fear I am not long for this part of the world. One day, the East India Company will be bigger than any sovereign nation on the earth. Some would argue that the day is already upon us. The locals are getting restless, the Buddhists are emerging from their slumber, thanks to the Bohemian ideas of that looney Henry Olcott. They are growing weary of the white man's rule and the Chinese have the cunning and the Indians have the gab to be their masters.

We can no longer run this world from Amsterdam, Lisbon or London and we should stop pretending we can. Our time is passing serenely but with haste and if you mean for me to throw more dice before I depart, then I need some guarantee that I will roll a six.

You are misinformed as to the legality of Cannabis sativa. The law is clear on the subject and the penalties for smuggling a narcotic do not distinguish between stimulant and poison. If we are to risk the gallows, why do it for a paltry three-score rise?

My proposal is you grow a crop that will deliver returns of exponential proportions. That can be harvested for a few hundred rupees and sold for a few thousand pounds. If the land you possess is as fruitful and as discreet as you say, then buying you out from a local disawa would be child's play.

Do not shake your head Lorenzo Fonseka. You may think you know what I am to suggest, but you may not. It is a crop both the East India Company and the British government would fund by proxy, we have already fought two wars with the China over it. The market for opium grows in the west among gentlemen like yourselves. But it is in the orient where the demand outstrips the supply.

I am weary of this continent and these paradises filled with thieves. A whore ceases to have allure once she has submitted to you a thousand times. None of us are Andrew Carnegie, and I doubt any of us dream of concert halls. It is no longer 1869 gentlemen. Let us plant our poppies while we can.

THERE WAS SHOCKED silence, followed by the settlement of bills. The bar was now crowded with tourists and locals. Thomas Maitland and his companion had long departed. Pipes had been put away though no hands had been shaken.

"I trust neither of you will see the need to discuss my proposal with your masters," stated Edgar Walker as a matter of fact. The other men shook their heads.

"There are no masters, Sir Edgar. Only us."

"We all have our masters, Fonseka. But very well."

"I would like to discuss the implications with Senor Lorenzo, if I am to be permitted," said Pieter van Cuylenburg. "May I give you my answer by tomorrow?"

"That would be agreeable," said Walker and hands were finally shaken.

They walk to the entrance of the Galle Face Hotel and watch the kids with kites, the teenagers with bats and the couples under umbrellas. Pieter hails a Bajaj three-wheeler, Lorenzo walks to his Toyota and Walker departs in a chauffeur-driven Benz paid for by the Company. The planter waves from his tuk-tuk to the shipping magnate who bids farewell to the gentleman from the bank.

"Is it true you are to be knighted Eddie?" asked the Portuguese before they departed.

"I bloody well should be," replied the Englishman.

Moments later in the back seat of his Benz, Edgar Walker texts his PA and sets up meetings for the next day. On the radio, two DJs are attempting comedy by mimicking British accents. One speaks like Noel Coward, the other like a character from a novel by Dickens. They banter for minutes and are neither funny nor accurate.

We don't speak like that anymore, thinks the Englishman. If you cannot learn to mimic us properly, how will you rule yourselves?

His chauffer pulls out of Galle Face Hotel into Colombo traffic. Edgar Walker looks at the colonial buildings sharing space with skyscrapers and dials a number. Somewhere in Beijing, a telephone rings.