The Arc of War

As the Middle East conflict spreads from Gaza to the Red Sea, there is hope yet for an optimistic outcome that can stabilise the region by bringing states closer together and countering the polarisation of recent years

Jason Burke

Jason Burke

Jason Burke

Jason Burke

|

19 Jan, 2024

|

19 Jan, 2024

/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/MiddleEast1.jpg)

The destruction in the Gaza Strip as seen from Nahal Oz in Israel, December 29, 2023 (Photo: Getty Images)

EVERY MORNING AND EVERY EVENING ACROSS ISRAEL, millions of mobile phones buzz and ping signalling that rockets heading for Israeli targets have been detected or, latterly, drones entering Israeli airspace. Three months ago, these prompted some concern for personal safety. More recently, there have been far fewer and, anyway, most people are used to them. Unless Hezbollah step up the intensity of attacks in the north, or Hamas make a sudden and unexpected recovery in Gaza, then the Iron Dome air defence system will deal with them.

In Gaza, of course, there are no such early warning systems for the civilians on the receiving end of Israel’s aerial and ground offensive. Israeli military officials describe huge quantities of leaflets dropped and phone calls made in an attempt to convince people to clear out of the battle zones but none of the 2.3 million people stuck in the territory since the beginning of this war has any app that signals incoming fire. Not that it would make much difference. Unlike the Israelis, or Hamas for that matter, they have no bunkers to run to.

As a journalist in Jerusalem, my days are determined by the rhythms of such alerts. If it’s not the rockets, it will be reports on X (formerly Twitter), alarmed calls from contacts, new fears voiced on multiple WhatsApp groups. All seek to warn of what may come in the next hours or, perhaps, days. Few are thinking much longer-term.

There are obvious reasons for this. We are currently in the middle of an atrocious and bloody conflict which appears to be escalating across one of the most volatile regions in the world with every day that passes. More than 24,000 are dead in Gaza, mostly women and children. More than 1,200 were killed by the Hamas attacks into Israel in October that triggered the war. Most of these casualties were civilians, and a hundred or so of those taken hostage that day remain in the hands of the militant Islamist organisation. From Yemen, the Houthis have attacked shipping in the Red Sea, bringing a sharp if possibly ineffectual response in the form of air strikes by the US (and in a very minor role, the UK). Iran has activated militia across Syria to attack US bases there and launched missiles against a supposed “Israeli spy complex” in semi-autonomous northern Iraq earlier this week. Clashes continue across the disputed border between Israel and Lebanon as Hezbollah, the biggest and best equipped Iranian proxy anywhere, signals its support for the Palestinian cause but, hopefully, stops short of an all-out war.

From Yemen, the Houthis have attacked shipping in the Red Sea, bringing a sharp if possibly ineffectual response in the form of air strikes by the US and the UK. Iran has activated militia across Syria to attack US bases there and launched missiles against a supposed ‘Israeli spy complex’ in northern Iraq

Amid this apparent chaos, any forecast appears rash in the extreme. No one predicted the initial attack by Hamas that sent us spiralling to where we are now, and this alone should put us off any bid to think too far ahead. Israeli officials now talk about the ‘Conceptzia’. The word was used here to describe the groupthink and complacency that in 1973 led the Israeli political and military elite to discount the possibility of an Egyptian attack until Cairo’s tanks had crossed the Suez Canal. Now it refers to the failures of analysis and imagination that meant no one foresaw what Hamas might do. “We thought maybe 30 of them might attack as a worst-case scenario, 300 seemed completely insane. As for 3,000, never in our wildest dreams,” a military intelligence officer told me shortly after the October 7 attack.

RIGHT NOW, ANY optimism seems wildly misplaced. The funerals are too many, the scars too livid, the fears too real, and justified as well.

There are many good reasons to worry about the months to come. The war in Gaza could get even worse, the Houthis or Hezbollah could provoke a new major confrontation; the risks of even unwanted escalation remain terribly high. There is even the possibility that the US, and so other powers, might be drawn in, with boots on the ground. If anyone had suggested this at the beginning of the civil war in Syria, they would have been laughed at. Now, with some suggesting that the Syria-fication of half the region is entirely possible, it would be wrong to reject the idea out of hand.

But seeking to see something better that might possibly come out of the mayhem is a useful intellectual exercise. It may help us answer the very obvious and important question: How will this crisis change the Middle East?

Optimistic is of course a very relative term in the Middle East at the moment. It may be more about hoping that the worst is avoided, but there are still some positive outcomes that are possible, despite the horror and tragedy seen so far.

One way this crisis might change the Middle East is to reinforce those existing trends across the region that ran counter to the polarisation of recent years and decades, both at the level of individual countries and more broadly across the region. You could call this the “centrist scenario”, as it involves dynamics that unite rather than divide, build consensus, not its opposite, and may possibly lead to a greater degree of stability. This would not end violence, of course, but might limit its extent and possibly allow a happier trajectory to take hold.

In recent weeks, under pressure from the US, Israel has begun a transition to a less intensive strategy in the territory. But discontent is growing, Netanyahu’s approval ratings are rock-bottom and his Likud party would be trounced in an election. At some point in the next six months or so, he may have to either remake his government or call an election

There is one big caveat to get out of the way first, however. This scenario, at the moment, depends on events not going even further off the rails. But let’s come to that later.

We should start with Gaza. In recent weeks, under pressure from the US and to help its own economy, Israel has begun a transition to a less intensive strategy in the territory. There are still appalling numbers of civilian casualties but the daily death toll is far lower than the horrific levels of the early part of the conflict as the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) battered their way through northern Gaza. Most importantly, the war has now reached a semi-stalemate. Hamas has suffered very significant losses, both in men and material, but the top leadership echelon is intact and it holds at least 100 Israeli hostages—and 10 non-Israeli nationals. Israeli generals now talk of the conflict lasting a year, possibly longer. The humanitarian suffering in Gaza is acute, with nearly two million out of the 2.3 million population now displaced, famine stalking, and a health service largely destroyed. But the breaking point of Hamas—its strategic centre of gravity—has not yet been reached apparently.

This has important consequences. The war has not been the success that Benjamin Netanyahu, the Israeli prime minister, wanted. He and his ultra-rightwing coalition partners can stay in power, and avoid blame for the catastrophic failures that led to the October 7 attack, as long as the war goes on.

But discontent is growing, Netanyahu’s approval ratings are rock-bottom and his Likud party would be trounced in an election. At some point in the next six months or so, Netanyahu may have to either remake his government or call an election. Optimists—and this is the optimistic scenario, you’ll remember—say that though Israel has swung dramatically to the right in recent decades and more so since the October 7 attacks as fearful, angry and grieving citizens seek a scapegoat, there is much else happening within Israeli society. The last year saw an unprecedented protest movement against a radical plan by the right-wingers to reform the judiciary as a first step towards turning Israel into an authoritarian state enabled by the most extreme form of messianic Zionism. This could form the kernel of a new centrist party or movement to pry the country out of the hands of the populist right.

The basis of this view is that the lesson of the October 7 attacks was that change has to come. If it does at a political level within Israel, much else is possible: concessions that might finally allow a peace process that has gone backwards for 30 years to make incremental forward progress, a recognition that ‘managing’ the conflict as Netanyahu has tried to do since first coming to power in the 1990s is impossible and that some kind of more permanent solution needs to be found. Like I said, this is the optimistic scenario and given the current polling of views in Israel on even the modest suggestions made by Antony Blinken, the US secretary of state, on his most recent visit, you would be forgiven some scepticism. But let’s hope for a moment.

The lesson of the October 7 attacks was that change has to come. If it does at a political level within Israel, much else is possible. This is the optimistic scenario and given the current polling of views in Israel on even the modest suggestions made by Antony Blinken, you would be forgiven some scepticism

As for Gaza, a political change in Israel could signal a very different end to the war. Netanyahu will never allow the Palestinian Authority (PA) in its present state to govern the territory. So, if he were gone, a new vista would open up. There might be a major international effort to reform and revitalise the corrupt, inefficient and unrepresentative administration of Mahmoud Abbas in Ramallah. The PA itself might even clean its own Augean stables under the shock of the recent war, with the incentive of reuniting the two territories of what was supposed to be the state of Palestine and receiving large quantities of cash, too.

This would allow the Gulf States to get involved in what will be the epic task of trying to reconstruct Gaza. This will likely take decades and cost hundreds of billions of dollars, if not more, given the extent of the destruction. On a short trip to the edges of Gaza City in November, I saw streets that had been obliterated. Nothing remained but rubble, stripped walls, twisted metal, and in the centre of it all a thin line of straggling, disconsolate residents walking away from what had been their homes. In my repeated conversations with friends in Gaza over recent months, one theme returns again and again: What is there to go back to when the war is over? Very little, is the answer. Schools, sewers, clinics, parks, homes, in short everything necessary for a vaguely decent life, has gone. “What do I tell my children? How can I offer them this life?” asked one friend, a 37-year-old father of three whose house and half his family are no more.

But this process of reconstruction could bring benefits, even in the short term. If the PA was running Gaza and the Gulf States were pouring in money, this would boost the process of normalisation of Israel within the Middle East that had been underway before the war. It is striking how those powers which had already signed up to normalisation agreements—the UAE, Bahrain, Sudan, Morocco— have remained broadly committed to them. Many analysts believe that Hamas launched its attacks three months ago to stop Saudi Arabia continuing its own moves towards such an accord. The noises from Riyadh in recent months suggest a temporary pause in this, but not more. Mohammed bin Salman, the crown prince and de facto ruler, still apparently sees a relationship with Israel, enshrined in some kind of binding agreement, as a key goal, whatever the anger on the street. The war may have actually reinforced this conviction, rather than the opposite. The history of the region teaches us that Gulf States will open their wallets for the Palestinian cause, but not sacrifice their core interests. Yasser Arafat recognised that in the early 1960s when first campaigning to raise funds for his new Fatah organisation. Little has changed.

Netanyahu will never allow the Palestinian Authority in its present state to govern Gaza. So, if he were gone, a new vista would open up. There might be a major international effort to reform and revitalise the corrupt, inefficient and unrepresentative administration of Mahmoud Abbas in Ramallah

And elsewhere? Well, Qatar may have to pay some kind of penance for its hospitality towards Hamas, even if this was something the US smiled upon, but contacts with Israel have strengthened, not weakened, in recent months. Note where Israel targeted a top Hamas official earlier this month: in Beirut, not Qatar, where the most important leaders are based. Nor has Israel targeted the Hamas officials in Turkey. Recep Tayyip Erdogan may have ramped up the anti-Israeli rhetoric, playing to his Islamist and populist base, but there are relations here that the men of Mossad and those who control them want to preserve. As for Egypt, President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi’s regime has had little difficulty containing popular anger and solidarity for the Palestinians, and is far from dismayed to see Hamas cut down to size. An Israeli delegation flew to Cairo last week to talk about plans for a hostage-release deal, ceasefire, and what happens when the war ends. At a state level, things have not fallen apart. So far, and possibly to the detriment of many ordinary people in the Arab world, the centre has held.

THE ALERTS THAT ping and buzz throughout Israel in the mornings and evenings now usually signal activity on the northern border.

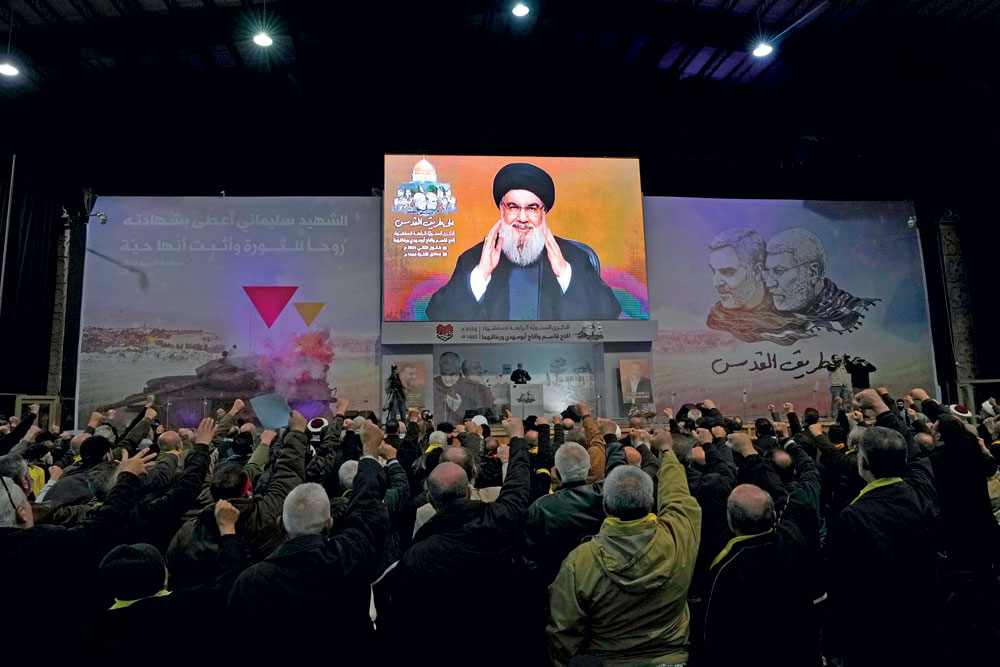

For those seeking reasons for optimism, this is a problem. There is a very real chance of war between Hezbollah and Israel, despite the clear desires of both to avoid a full-scale confrontation. The clashes along the border have been steadily escalating over recent weeks, and the chances of a miscalculation in the finely calibrated equilibrium of violence are mounting. A Hezbollah drone hit the headquarters of IDF’s northern command earlier this month. It did little damage but could have, by chance, killed a general. This would have been impossible for Israel to ignore—even if its leaders are well aware of Hezbollah’s formidable military capacities and arsenal of 150,000 rockets. At the same time, there are still 80,000 Israelis from communities close to the disputed border who cannot return home for fear that Hezbollah’s elite Radwan force would do in the north what Hamas did in the south. “The situation is intolerable,” an Israeli government spokesman told me. “The situation is intolerable,” says Hassan Nasrallah, Hezbollah’s leader.

As for Hezbollah, Tehran sees the powerful militia as a crucial deterrent to Israel and the US. Would the clerics risk such a shield, built up over four decades or more? That is unlikely. They are rational actors who have carefully avoided direct confrontation with their supposed worst enemies: the US and Israel

But this does not mean a war is inevitable. There is much clever and careful diplomacy underway, and the Israelis are signalling that, despite more expansive demands, they would be satisfied for the moment if the Radwan force were moved away from the border. There is even an outside possibility that the vexatious arguments over the exact line of the frontier might be settled once and for all.

The key here, as in the region as a whole, is the attitude of Iran. The Axis of Resistance built by Tehran over recent decades is a loose coalition of autonomous groups. Its members—Hamas, Hezbollah, the Houthis, sundry Iraqi and Syrian militia—have their own agendas and interests although they benefit greatly from Iranian funding, expertise, weapons, and much else. Hamas did not tell Tehran in advance of what was planned for October 7, greatly irritating its sponsors. This has led to a certain chill in relations—an important factor going forward.

The Houthis, in contrast, are unlikely to be firing rockets or otherwise harassing maritime traffic in the Red Sea without orders from the clerical regime that has backed them so heavily in the proxy conflict that is the civil war in Yemen. But here, too, there are limits. Iran and Saudi Arabia are enjoying a slight detente and a peace deal in Yemen was supposed to be signed this month to allow Riyadh to extricate itself from the conflict there. Neither power wants to jeopardise its better relations just for the Houthis and a few missiles aimed at ships.

Many analysts believe that Hamas launched its attacks to stop Saudi Arabia continuing its moves towards an accord. The noises from Riyadh suggest a temporary pause in this, but not more. Mohammed bin Salman still sees a relationship with Israel as a key goal, whatever the anger on the street

As for Hezbollah, Tehran sees the powerful militia as a crucial deterrent to Israel and the US, and so protecting Iran and its interests well beyond Lebanon. Would the clerics risk such a shield, built up over four decades or more? That is unlikely. They are rational actors who, since taking power in 1979, have carefully avoided direct confrontation with their supposed worst enemies: the US and Israel.

There are lots of pessimists in the Middle East and with good reason. How not to be so when surrounded by such loss and violence and suffering on a daily basis? The worst-case scenario for the current crisis is truly terrifying. The optimistic scenario neither denies that grief and pain, nor should it lull us into a new Panglossian Conceptzia. But it can throw up some useful ideas of what might come next, and how this awful war might change the Middle East, or not.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover-Shubman-Gill-1.jpg)

More Columns

‘Fuel to Air India plane was cut off before crash’ Open

Shubhanshu Shukla Return Date Set For July 14 Open

Rhythm Streets Aditya Mani Jha