Tell Me How to Be

I’m about to lock the door behind me when my mother sighs softly into the phone.

“Akash,” she says.

Her voice is uncharacteristically small.

“There’s something else.”

“What?”

She’s silent, the static sizzling between us. “It’s the house,” she says. “What about it?” “It’s sold.”

I picture it: white brick with a slate roof, ivory pillars, trimmed hedges, and windows that reflect pinkish- gold whorls at dusk. All week long, I’ve prepared for my return, reimagining every glossed surface, every cozy nook. “The house? When did you— I didn’t even know it was on

the market.”

“Well, you don’t call home.”

I think back to the last time I called my mother. It must have been June, or was it April? A rare wet day. Strong winds rattled the floor- to-ceiling windows in Jacob’s condo.

“When do you move?”

“Next month.”

“That soon? To where?”

She’s silent, and I fear she’s going to say she’s coming to Los Angeles. Jacob has been talking about her recently, that he would like to meet her, that we could fly down for Thanksgiving, or maybe she would like to attend his cousin’s wedding in Newport Beach, wouldn’t that be nice? We don’t talk about the truth: that my mother has no idea who he is, that in her world people like Jacob don’t exist.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

When she answers, her voice is resolute.

“I’m moving back to London, Akash. I’ve made up my mind.”

“London?”

“I’ll explain everything when you come home. This will be the last time you see the house. The last time you see— everyone. All our memories are here.”

The word “memories” is like the sharp nick of a blade, breaking skin.

“But what about— ”

Suddenly, the door opens and Jacob’s bearded face appears in the light, his hair slicked over. He puts his arm around my waist. “What’s wrong, babe?” I want to shush him, press his back against the wall, but it will only make things worse, so I say nothing instead, letting his fingers glide up my shirt, pinching my nipple. I close my eyes. I know it’s too late, because my mother asks, “Is someone there?”

“No, Mom,” I say. “It’s only me.”

R E N U

My husband liked me to wear makeup around the house. “Come, Renu,” he’d say. “Taiyar thaija.” According to women today, this would make him a bad man. I never questioned his motives. I never said, “Why? Don’t I look good without it?” Instead, I powdered my face, applied lipstick the color of red wine. Sometimes I tried on an expensive gown, something I’d bought at one of the posh stores when Ashok was not around. I turned side to side, batting my eyes like Susan Lucci in All My Children. I liked Susan Lucci. I liked it when she slit her eyes and said something nasty like, “I know you’re sleeping with my husband, Cassandra— you whore!” then turned around and slept with someone herself. Everyone was sleeping with someone on these shows— slapping people, too. Sleeping and slapping, sleeping and slapping. Until it was time to throw a drink in someone’s face. Such vile disrespect— I liked it. Before I moved to this country, I had assumed all American women were whores. I was wrong. Not all American women are whores. Only the ones on TV.

I would not have chosen to live in this town with its quiet roads and its dark winters, but back then, I didn’t have much of a choice. I married Ashok. He brought me to Illinois. There was no alternative. I could not have been what the whites call a “spinster,” drinking martinis at three p.m. According to my parents, women like those were failures. They were dangerous. But what’s so wrong with a dangerous woman? Women have choices now: what to wear, whom to marry, even whether to be a woman at all. It’s all fine with me, as long as everyone shaves their legs. I didn’t choose this life for myself, but now I’m choosing to leave it. The women in my book club say this is very feminist. They’re all very young and very blond and very excited— about everything. I made the decision to move six months after Ashok died, contacting a Realtor and putting the house on the market, replacing the carpets and doors, fixing the leaks in the gutters, doing all the things Ashok had been meaning to get done before he passed, before God took him.

I don’t wear makeup around the house now. I don’t do a lot of things I used to do, like preparing a full Indian meal: vegetable, lentil, roti, rice. I don’t chop mint leaves for cucumber raita. I don’t set out jars of pickled mango, floating in red oil. I don’t stock the refrigerator with Ashok’s favorite cheeses and wine. Sometimes I don’t even buy groceries at all. Instead, I eat simple things, sandwiches and soups, cereal with milk, Chinese takeout or Thai, watching the sun set behind black, skeletal trees. It’s the first time in my life I’ve been alone.

Before marrying Ashok, I lived in a small flat in London with my brother and his wife, working in a pharmacy nearby. I can still see the red buses and perpetual silver drizzle, the small Peugeots with their mustard-colored plates. I can see the sleek shops on Oxford Street selling cashmere and silk, luxuries I couldn’t afford at the time but now, with millions in my account, can buy in bundles if I like. I lie awake at night and dream of the day I will return, landing at Heathrow Airport, walking along the Thames. Maybe I’ll buy a flat, one of those chic glass cubes that jut out like cut quartz in the sky. I have languished in this town with its Walmart and its Applebee’s, its quiet, rural roads, where I was known only as Mrs. Amin, only as Ashok’s wife, only as Bijal and Akash’s mother, and where I have thought, even after all these years, only of you.

Kareem.

A K A S H

It’s the morning after my mother called and I still can’t believe it. The house: gone. My mother: gone. I had planned only to honor my father, to preserve his memory among family and friends. But now everything’s changed. I suppose I had taken it all for granted: the house, my mother, that town— even you. You’re all I’ve thought about this morning. Your dark eyes still flicker in my mind. But then there’s Jacob, lying next to me in bed. Jacob, scrambling eggs over the stove. Jacob, sipping orange juice while reading The New Yorker on his sun-soaked deck. Jacob, following me into every room.

“Why can’t I come with you?”

“Because it’s a family thing.”

“Then what am I?”

Not family, I want to say. Instead, I tell him it isn’t the

right time.

“It’s never the right time.”

“That’s not fair.”

“To whom? You, or me?”

He follows me into the bedroom as I fold underwear and T-shirts and stack them into neat piles, then slide them into a carry-on bag. I can feel him breathing. I can see his face, the small emerald eyes, woolly beard, chestnut hair sculpted back with pomade. The tight line his lips make when he’s angry or sad. This time it’s both. He wants to know when I’ll be back. I have no answer. I don’t want to tell him about my mother; I don’t know why.

“It’s my father’s anniversary. My mom will want us to hang around.”

I had only just met Jacob when my father died. Perhaps that’s what drew me to him: the loss of one man driving me into the arms of another. We met on Tinder. Later, I’d stalked him online. Jacob played the violin. He owned a beagle. He had a sister named Emily; she was in pharmacy school. I’d memorized her name. Emily. Emily. Emily. Later, when Jacob mentioned her on our first date, I’d smiled.

“Ah, Emily,” I’d said, as if we were old friends. “The pharmacist.” Later, he would tell me it was this that made him fall for me: my eagerness. He was my first boyfriend. When he’d asked me to move out of my dark studio in North Hollywood and into his light-filled condo in Santa Monica, I didn’t have to think very hard. It was simple: I was twenty-eight, a struggling artist. Jacob was thirty-seven and owned a successful business. He cared for me like a father would, holding me accountable for my goals. He took an interest in my career as a songwriter, listening to demos and promising to connect me with people in the industry, managers and record label executives, people I never actually met. Sometimes I wondered if he dangled these opportunities just to make me stick around.

Now, I can feel Jacob watching as I zip my bag shut, slide an extra pair of socks into the front pocket, and check to make sure the whole thing isn’t too heavy.

“Don’t forget dinner tonight,” Jacob says.

“Nathan organized it. The whole gang will be there.”

“Okay.”

He’s silent. “So you’ll come?”

“Of course I’ll come. Why wouldn’t I?”

I regret my tone. I can sense Jacob’s injury when he says, “I just want you to be close to the people I’m close to, Akash. Even if it’s not the other way around.” I don’t like Jacob’s friends— especially Nathan. I can already picture it: a bunch of white queens in rompers making snide remarks. Everything will be “terrible” and “horrendous.” I don’t know what Jacob sees in them. Once, Nathan told me it was a shame my country is so homophobic given how spiritual it is. When I reminded him that my mother is from Tanzania, not India like he had assumed, he’d swatted the air. “Don’t get me started on them.” I’d fought with Jacob that night, saying the only thing worse than a straight white man was a gay one— because gay white men conceal their racism with sequins, while straight ones wear it proudly on their sleeves. My father once said the most dangerous creatures in the jungle are the ones you don’t see. Mosquitos fat with malaria. Tiny, poisonous frogs. Jacob said he was sorry— though for what, it wasn’t clear.

Still, I know he tries. When I come home from work, he rubs my shoulders. When I cry out in the middle of the night, he cradles me in his arms. Once, moments after I’d vomited in an Uber on the way home from a bar, he kissed my mouth. I had recoiled, but Jacob just shrugged. It’s only puke. That was before, when the newness of Jacob and me was like the first spritz of a perfume, fresh and sexy, before it dried down to an odor that was

ultimately too intense.

“Look,” I say, my back still facing him. “Once I get down there, I’ll talk to my mother. I’ll tell her about…us. I’ll tell her everything. Maybe you can meet her.” I swallow hard, wondering if he can hear the hollowness in my words, but when I turn from my packing, Jacob is gone.

R E N U

I’ve never liked American grocery stores. They’re too cold. Too many products line the tables and shelves. There are fifty different cereals but only two types of green chilies, and neither one of them has any actual heat. On TV, white women tell us to remove the seeds and the ribs— otherwise it’ll be too spicy.

“Oh, for god’s sake,” I want to tell them. “Just eat a bell pepper.”

Sometimes a cashier will smile at the person in front of me, but when it’s my turn, her face turns to stone. What’s your problem? I want to ask. But I’m too afraid. In London, I learned to stare back, talk back, fight back. In London, there were others like me, doing the talking and fighting. But in America, where people still ask me where I’m from, and how I got here, and to what church I belong (none— I’m a Hindu), I keep my mouth shut. Don’t make waves, Ashok liked to say. Don’t act fresh off the boat, Bijal whined. Don’t rock the boat, Mom, Akash once said. Just chill. I don’t understand this American obsession with boats.

My cart squeaks against the polished tiles as I drop items into it without a thought. I remember those early years, when Ashok was in residency and we lived off a paltry sum, price tags compared, coupons clipped. Now, I don’t hesitate to buy thick blocks of parmesan with perforated rinds, fresh mozzarella, Marcona almonds, the pressed coconut water Bijal likes to drink. I buy everything the boys will need. My heart swells with the thought of their footsteps on the stairs and their baritones in the kitchen, their laughter, their smells, the timbre of their rage. I miss them— even Akash.

“Excuse me,” someone says.

My gaze slides toward a young woman in yoga pants and a sweatshirt, her brown hair scraped back with sweat. Her cheeks redden. She walks over to me with authority, and I prepare myself for her words. You can’t be here. Don’t touch that. Are you a customer in this store? It has happened before, women like her smiling their plastic smiles, then telling me what I can or cannot do. She holds a package in her hands.

“I was wondering,” she says, nervous. “I thought I’d ask—”

“Yes?” I clutch my bag to my chest.

“This brand,” she says. “Have you tried it before? Is it good? Authentic?”

She pushes a package of frozen Indian food in front of my face. I sigh with relief. Years ago, Ashok and I would have never imagined Indian food at the grocery store, but now there’s a whole section, boxes upon boxes of chicken tikka masala, rounds of charred naan. The woman presents a package of malai kofta I’ve tried before. The kofta tasted like feet.

“Oh, it’s lovely,” I say, smiling. “Really?”

“Mm! Tastes just like home.”

“Oh, wow.” The woman grins.

“That’s a relief. Thank you. My husband and I just love Indian food.”

“How nice.” I start to walk away. She follows from behind.

“My roommate from college was Indian,” she says.

“That’s how I tried it. Her name is Devi.”

I turn, forcing a smile. “A wonderful name.” “It means goddess.”

“Yes, I know that.” “Oh, of course.” She smiles, chagrined. “I just love it. It’s so feminist.”

My smile disappears. Bijal’s wife, Jessica, is a feminist. She thinks I’ve spoiled him, cooking his dinners and folding his underwear all those years. In my opinion, the most feminist women are those who don’t need to call themselves one— not like these American women, who are just looking for reasons to complain. I could tell Jessica this, wipe the grin off her face, but I’ve only seen her three times since their wedding. Save for the girlish arcs of her cursive on holiday cards, she’s a mythical creature, spoken of in hushed tones.

“Well, I think I’ll be off,” I say, rounding the corner. “Enjoy the food.”

“Thank you!”

I can feel her eyes on me as I make my escape.

I unload the groceries in the kitchen. It’ll be a shame to leave it behind: the bone-white marble, flecked with gold, the Viking stove, the pearled cabinetry, polished to a high shine. A set of windows overlook the wooded backyard and slate-gray clouds. Evening settles in a navy cast, shading everything in relief. Twenty days. That’s all I have left.

I was surprised when the Realtor told me we had an offer. When she’d first come around, six months earlier, she’d had her doubts. “A house this size, at this price. In this town. I don’t know.” She’d run her toes over the slick tiles, staring up at the cathedral ceiling. “Not many people can afford it.” Apparently, someone could. I don’t know who the family is. As soon as the offer came in and was accepted, I knew what I had to do. I phoned my brother and his wife in London and told them I was coming home.

I pour myself a glass of wine. It’s a new habit: drinking alone. I wasn’t like Ashok, who would come home from work and pour himself a scotch, or Bijal, who would twist open a beer after mowing the lawn— or Akash, who never needed a reason in the first place. Drinks are for celebrations, I’d once told him. What do you have to celebrate? The wine warms my chest as I carry it through the house, making a note of what furniture will be donated to charity and what will be given to friends, the arrangement of tables and chairs for Ashok’s puja next week. It will be the first time I’ve had guests in this house since his wake. And the last. I move between these walls like a ghost, floating up the curved stairs. The master bedroom feels cavernous without him. Sometimes I can still smell the mossy scent of his cologne. I set my wine on the nightstand, switch on a lamp. I see my reflection in the windows ahead. My shoulder-length hair has gone gray at the roots. My pale skin is shadowed. My waist is narrow, my hips slim. The lamplight falls in a vertical strip across the linen duvet, like a gold ribbon. A gift.

A K A S H

When I was young, I dreamt of living in a condo just like Jacob’s, with its mountainous views and rich, golden light. The living room features a distressed leather sofa and beechwood coffee table. Twin bookcases sandwich a flat-screen TV. Japanese silk paintings hang from opposite cement walls. Organic fruit spills from a basket at the center of the kitchen island, which is made of white quartz. Plums. Nectarines. Clementine. Pears.

We don’t keep booze in the house— not since the time I got drunk and hurled a bottle across the room. We’d had a fight; I don’t remember why. Jacob wouldn’t tell me. I suppose it was his way of shutting me out. It only drove me to other doors. Often, after a booze-fueled night, I would wake up with an icy sensation that something had gone terribly wrong, that I had left my own body, and gone to a dark place, and that my life had irrevocably changed. Then I would find a text message I’d sent from my phone, something cruel or nasty I had no recollection of writing. Recriminations. Insults. Sharp, cutting words. I promised not to drink tonight. I’m going to be good.

I walk into his office and slide a pair of headphones on, connecting them to my iPhone. I play the track I recorded weeks ago.

I was going for a ’90s vibe, something smooth. R&B, the only music I’ve ever loved. Aaliyah, Brandy, Monica, TLC. I can still recall the way boys pounded the beat to Aaliyah’s “One in a Million” on their desks: rat- tat- tat- tat- tata- tat- tat. Rat-tattat-tat. Your love is a one in a million. It goes on, and on, and on. We had never heard anything like it. Remember? Sometimes I joined in, freestyling over their percussion, arranging my own melodies, until someone would look at me and say, with wonder in their voice, Damn, Osh. You got skills. And for that brief moment I existed, I was real, a stray piece of thread woven into the fabric.

Now, I hear my voice and wince. At the time, I had been thrilled with it, blasting it from the Bose speakers on Jacob’s shelf, but something is off. The first verse goes against the beat instead of gliding on top of it. The hook is predictable. The whole thing lacks melody, which is frustrating, because melody is my thing. I stop the track, yank the headphones off my ears. I walk into the kitchen and pop my face in the fridge. The blast of cold air invigorates me. I poke blindly between jars of pickles and roasted red peppers before my fingers latch onto a familiar metal cap. The flask is where I last left it, behind the energy drinks and protein shakes Jacob hates, full of artificial flavorings, the last place he would ever think to look.

R E N U

I sit in Ashok’s office in the lamplight, surrounded by books. I pull up Google, enter your name. It’s impossible to find you among the results: Instagram pages, YouTube links, LinkedIn profiles. None of them are you. Once, on Google, I’d clicked on an article about the arrest of a man with your name, my heart ricocheting in my chest, but the picture was of someone much younger. I don’t know what you look like now, Kareem. It’s been thirty-five years.

Ever since I booked my ticket to London, thoughts of you have been flooding back like pieces of an interrupted dream. I need to distract myself. I move about the house, making sure everything is in order. I fluff pillows, snap sheets into place. I stand in the kitchen boiling a pot of tea.

I was sixty when Ashok passed. No one expected him to. We had the kind of bright life people dream about, full of half-truths and lies. The night before Ashok died, he devoured the pressure-cooker lamb chops with coconut masala I had prepared for his dinner, his lips glistening with fat.

“Renu, I love your food,” he said. “I could die eating this.” And then he did.

At least he left this earth with good food on his tongue. This was the thought that comforted me the next day when he didn’t come down for his cup of tea, and, later that morning, when the paramedic pronounced him dead, and, in the days that followed, through all the phone calls and emails and texts. He loved my food. All my boys did. They ate with abandon, licking fingers, sucking bones.

“Mom!” Bijal said whenever he walked through the door. “What can I eat?”

He would stride around like a giant, opening cabinets and drawers. Sometimes, if I happened to be cooking at the stove, he would reach around me and pinch whatever was sputtering in the pan, popping it into his mouth. Once, I was making chicken fajitas when Bijal plucked a piece of chicken and swallowed it down.

“Bijal! That was raw!”

He shrugged. “Tastes good to me.”

When Bijal was nine and Akash was five, Ashok was invited to the home of a colleague named Dr. Shaw. They lived in a blue Victorian. Their dining room sparkled. Dr. Shaw’s wife, a thin blonde named Georgia, made roast chicken for dinner.

“Mom.” Bijal kicked me, whispering. “I can’t eat this. There’s no spice.”

Georgia had overheard. “I’m sorry,” she said, looking not at Bijal but at me. “You must be used to eating very spicy food.”

“Not very spicy,” I snapped. But Georgia only laughed.

“Well, I have no taste for it. Everyone knows that. Salt and pepper do just fine.”

“The chicken’s delicious, Georgia,” Dr. Shaw said. They never invited us again.

“You see?” I later said, invoking them as a warning. “You see what happens when you marry a white girl? You get bland food every day.”

“I don’t want to marry a white girl, Mommy,” Bijal said, kissing my hand. “I want to marry you.”

I snuggled him to my breast, temporarily pacified. Twenty years later, he introduced me to Jessica.

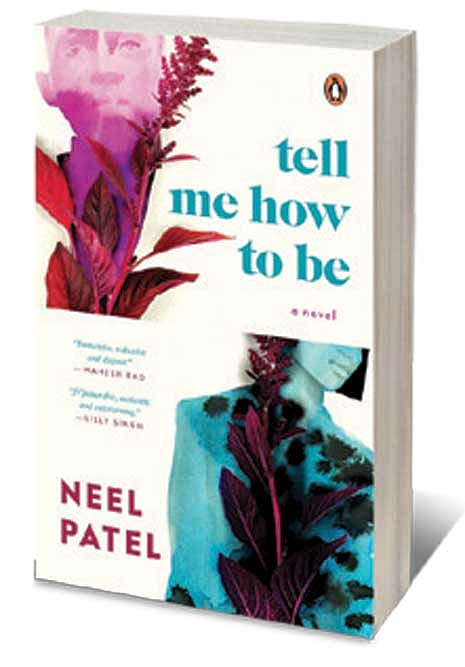

(This is an edited excerpt from the novel Tell Me How to Be by Neel Patel)