Sunset on Khan Market?

IT WAS AROUND OCTOBER 2016, I was working with India Today, and we had organised a series of conversations between two film legends from different generations. There was Ranveer Singh, who came in early and locked himself up in a conference room in a suburban hotel to work on pages of notes, which he would then edit and put on index cards. Back then, Ranveer was totally involved in the character, Alauddin Khilji, that he was to play in Padmavati (the film’s title had to be later changed)—he had grown his hair, sported a moustache and worked on his diction. “Alauddin Khilji was from so many different places that the accent was difficult to nail down,” he explained, as he sat at a table strewn with his notes, waiting for Aamir Khan to arrive. Aamir came straight from recording an episode of Koffee with Karan, accompanied by his two young co-stars in Dangal, Fatima Sana Shaikh and Sanya Malhotra. They were working as his assistants in the post-production phase of the soon-to-be-released film.

Ranveer was excitable, asking questions, admiring the depth of Aamir’s eyes and talking about some of Aamir’s best performances. Stroking his moustache and beard, Aamir looked embarrassed, but asked suitably interested questions, especially about those of Ranveer’s films that he had watched: Band Baaja Baaraat, Dil Dhadakne Do and parts of Bajirao Mastani. It was like watching a master and his pupil, guru and devotee.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Two years later, the two generations represented by Aamir and Ranveer went head-to-head at the box office. Data from media analyst Karan Taurani shows that in 2018, stars like Ranveer Singh, Ayushmann Khurrana, Vicky Kaushal, Shahid Kapoor and Ranbir Kapoor out-performed the over-forty stars in the number of film releases (forty-six against thirty-eight) and did better at the box office (Rs136 crore vs Rs108 crore), suggesting that there was now, in terms of casting, an alternative for producers, who were accustomed to taking home only 10 per cent of the total revenue because of the high cost attached to having A-list stars. Now there was clear evidence that entertainment did not necessarily mean the Khans.

When 2020 dawned—for the first time since 1988, when the three Khans made their debut— none of the three was the subject of popular conversation in India. Shah Rukh Khan was nursing self-inflicted wounds from the failure of Zero (with its unfortunate title). Aamir Khan had started shooting Laal Singh Chaddha, a remake of Forrest Gump, in an effort to make it in time for his customary December release. Salman Khan was manfully trying to keep it together, taking his muscles and the bags under his eyes to the sets of Radhe: Your Most Wanted Bhai, which was meant to be out on Eid 2020.

AFTER THREE DECADES of entertaining India, and increasingly the diasporic world, the era of the Khans, all born in 1965, seemed to be petering out. The ‘Actor Forever in Search of a Character’ had not had a single release after the disastrous attempt at playing the is-he-good-or-is-he-bad thug in Thugs of Hindostan in 2018. ‘Rahul/Raj the Romantic’ looked increasingly tired and worn out. And yet, his innate intelligence shone through whenever he was himself, as evident in the TED Talks India: Nayi Soch or My Next Guest Needs No Introduction with David Letterman. Suddenly, as he showed off his cooking skills to Letterman and spoke of growing up in Delhi, India realised why it had fallen in love with this man, with his odd hair and unnerving intensity. It was the same with Salman Khan, whether he scolded Bigg Boss contestants for misbehaving, flirted with Katrina Kaif on-screen in Bharat or adjusted the dress of co-actor Saiee Manjrekar who, at 21, was young enough to be his daughter, at a promotional event for Dabanng 3.

In the dying light of the Khan Kingdom, a new India was establishing itself. It is an India that seems to have little patience with the old platitudes of pluralism and multiculturalism. It is an India where the mandal, mandir and market mobilisations of the 1990s have merged with the rights-based legislation of the 2000s to create a new narrative of populist aggression. What was once considered a privilege is now seen as a necessity, whether it is a telephone connection, a gas cylinder or a toilet. In this India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, having been re-elected in 2019 with an even bigger majority in the Lok Sabha than in 2014, embodies the newly assertive way of dealing with the domestic margins and the global mainstream.

This is an India where identities are being transformed and internal borders are being redrawn. As promised by the BJP in its election agenda, in August 2019, Union Home Minister Amit Shah announced the abrogation of Article 370 and 35A in Parliament, which resulted in the bifurcation of the state of Jammu and Kashmir into two Union territories: Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh. The Kashmir Valley was placed under a virtual lockdown with communication snapped and political leaders placed under house arrest. In November 2019, the Supreme Court’s final judgment in the Ayodhya dispute ordered the disputed land to be handed over to a trust (to be created by the Centre), which would have the authority to oversee the building of the Ram Janmabhoomi temple. Completing this sweeping transformation of the political and social landscape was the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019.

By articulating ideas from political meritocracy to menstrual hygiene, by implementing decisions long pledged by the BJP, Prime Minister Modi has colonised the Indian imagination, leaving very little space for other icons. His relentless publicity machine has ensured that he, more than any other public figure, now helps India understand itself. This was what the Three Khans had once done, in their own ways, helping Indians navigate from tradition to modernity, as they themselves moved from the callowness of youthful romances to bigger themes. India had seen itself in the three of them.

But by associating their stardom with Prime Minister Modi’s various projects, whether it was Swachh Bharat, demonetisation, or even the celebration of Mahatma Gandhi’s 150th birth anniversary where both Aamir and Shah Rukh made flattering speeches and took obedient selfies, the Khans have effaced their own primacy in the cultural space.

Add to this the fact that the old certainties that created the conditions for the three-decade domination of the three stars has vanished. As sociologist Shiv Visvanathan says, “The triangle of contemporary Khans has to be understood within a rough genealogy of heroes. The Fifties saw the dominance of Dev Anand, Dilip Kumar and Raj Kapoor. There was something urban and urbane about them. The first two embodied the middle class hero while Raj Kapoor brought a hint of Charlie Chaplin’s tramp to add a touch of socialism. The late Sixties provided the space to two heroes who dominated the screens as individuals. The first was Rajesh Khanna who exuded a poetics of romance. This gave way to the myth of urban violence, epitomised by Amitabh Bachchan as the Angry Young Man. The next triangle was a set of composite, equivocal figures whose heroism needed time to develop. These were the Khans. Each began with a touch of adolescence which they then tried to shrug off in their own way.” Salman became the eternal adolescent, says Visvanathan, the boy-next-door who never grew up. Aamir, the autodidact, matured the most, attempting a more serious sense of himself in experimenting with a historical movie like Lagaan (2001) and Dangal (2016), the biography of a wrestling family. Shah Rukh was more ambivalent. Growing old seems to be the toughest for him, caught between the changeless Khan and the perpetually changing Khan. And time has been hard on him. ‘People watching his movies often ask, “How did I like this guy?” Yet the lives of millions, from youth to middle age, have been marked by him in some way. He marks all of us growing up. He is the common denominator of the Khan in all of us, a middle-class hero, an outsider, a man who has made it on his own,” says Visvanathan.

2020 was expected to be the year in which there would be a resurgence. There were rumours that Shah Rukh would start, and perhaps complete, a film with Raju Hirani that would restore his street credibility, and Salman and Aamir would be back with entertaining blockbusters. But it was not to be. Covid-19 struck the world and by June 14th, when thirty-four-year-old Sushant Singh Rajput died, apparently by suicide, the industry had changed beyond recognition. Suddenly, from a huge sympathy wave for a young death, conspiracy theories began doing the rounds, creating a media storm. It was said that yet another promising outsider had fallen at the barricades erected by the powerful in Bollywood. Clips of Rajput being mocked on Karan Johar’s Koffee with Karan by other guests went viral. Stories that made the rounds suggested that Aditya Chopra had short-circuited Sushant’s career by dropping the idea of making Paani, directed by Shekhar Kapur, in which the young actor was cast in the lead.

At a time when the Khans could have spoken up for the hurt and rage within and outside Bollywood, they chose to be silent, and that included Shah Rukh, the man whom Sushant had most publicly admired and emulated. Starting by questioning the suicide theory, the Sushant case soon became about money laundering by his girlfriend, actress Rhea Chakraborty, and when that couldn’t be proved, it became a drugs investigation in which a series of top stars, male and female, were named and shamed.

The discourse went from the survival of the Khans to damning the whole of Bollywood itself. Apoplectic anchors, whose channel ratings rose with their continued coverage of the Sushant Singh Rajput case, provided a platform to voices like that of Kangana Ranaut, who threw in the narrative of anti-nationalism, a clever ploy to bring religion into the conversation. The deification of the mafia in movies, the outpouring of support from the industry when Sanjay Dutt was accused of terrorist activities under TADA in 1993, and the rule of male actors who allowed women only item songs and a couple of romantic scenes while also expecting them to behave like their wives on the sets—Ranaut’s list of harsh accusations against the industry were many, and if some were self-serving, she admitted as much. “If I won’t destroy my enemies, who will?” she asked on Twitter.

The anger against Old Bollywood got powerful extra-territorial support from Rajya Sabha MP Subramanian Swamy, whose supporters saw in it yet another opportunity to boost his image as the hero of the Virat Hindu Samaj. At the same time, BJP leader Muralidhar Rao, BJP general secretary and great proponent of family values, and Prasoon Joshi, the chairman of the Central Board of Film Certification and the BJP’s unofficial poet laureate, saw in all this upturning of reputations an opportunity for Bollywood to craft a new form of storytelling inspired by ancient texts and contemporary history, rather than the narratives it had always fed off on.

MOST OF THE BOLLYWOOD biggies, among them Aamir and Shah Rukh, were participants in one such conversation with Prime Minister Narendra Modi in October 2019 in Mumbai, where the latter spoke of cinema’s potential for ‘nation-building’. Pro-establishment actors such as Akshay Kumar jumped in, even if somewhat late, asking for Bollywood to look within, at its own faults and flaws. As Visvanathan notes, “It is clear that Bollywood needs to fix itself, having come apart as myth and grammar. The old oppositions do not work. Violence is no longer heroic, the epic act that

Amitabh Bachchan dreamt of to resolve a social crisis. It is all-pervasive, inventive, endemic and institutional. The imagination of the city as holding together rural and urban is over. The city dominates as a demography but not as an ideology. The small town is offered as an intermediate solution, but it inspires as sociology, as market, but not as myth. The family and the mother are sacred but given domestic violence, this plot does not hold. Friendship and peer groups seem more logical and more important today. The personal and the public have got separated, so there is no Bollywood balance between the two.”

Bollywood tried taking to historical movies to solve the problem of a disconnect between the audience and itself. But that genre tried to look at the past more as a costume ball, dressed by Sabyasachi and designed by Sanjay Leela Bhansali, rather than as an examination of history. There is a highlighting of forgotten stories but a failure to work the epic as metaphor. Also, figures in history have become fragmented among caste groups. Bollywood has no answer to technology, no sense of science fiction. Music, Hindi cinema’s great strength, has taken a backseat in recent films, which means that songs cannot carry a film as they once used to. The solo scriptwriter and even the solo lyricist is fast disappearing, and in their place, a team of writers and more than one songwriter are given the task of writing the songs—but, ultimately, if the script fails to surprise or entertain, even the stars can’t save it.

Bollywood has failed to create a convincing kind of entertainment, which can subsume the changes one sees in the body, sexuality, gender, desire and even the erotic. The myth of youth does not work. They do not challenge the establishment, they want to be co-opted.

Sadly, the Khans—who, as their co-star Twinkle Khanna notes, have nothing in common except their surnames—had little to offer during the Covid-19 crisis, except a few tepid songs from Salman, who was clearly bored in his Panvel farmhouse. They have aged happily in their personal life as larger-than-life epic characters. They have degenerated into weaker versions of themselves, points out Visvanathan, mimicking themselves into oblivion, somewhat like Dev Anand.

Bollywood has to compete with the growth of streaming services, which are fast emerging as an alternative to the theatrical experience. The Covid-19 lockdown has changed audience tastes to a considerable extent. Not only have people got used to watching long-form storytelling with diverse characters and intriguing storylines, but they have also been exposed to a new world of global TV series and movies. Even the more popular entertainment meant for the masses, the equivalent of the proverbial front benchers, has acquired some degree of authenticity and sophistication. As the protagonist of ALT Balaji’s Bichoo Ka Khel puts it: “Aap apni kahaani likho, nahin to koi aur likhega. (Write your own story, otherwise someone else will write it for you).”

SHAH RUKH’S IDOL: He became the romantic icon for millions with Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge but whom did Shah Rukh Khan emulate?

Even though music was deciding box-office success, Shah Rukh Khan, with a growing number of blockbusters under his belt, was only too willing to proclaim himself the next Bachchan, perhaps a subtle way of shaking off any competition and placing himself firmly in the same league as the Angry Young Man. In December 1994, in a Filmfare interview, he stated: “Whenever I’m asked to do a drunken scene I think of Amitabh Bachchan.” A few months later, in a July 1995 interview, he elaborated: “I’m waiting for the day they say ‘do it the Shah Rukh Khan way’. Right now they’re doing it the Amitabh Bachchan way.” The December 1994 edition of Movie magazine had Shah Rukh and Amitabh Bachchan on the cover, with the headline ‘Heir Apparent?’

It was a theme that Shah Rukh and his work would return to again. The next decade would begin with the face-off between Bachchan and Shah Rukh Khan in Aditya Chopra’s Mohabbatein (2000). The competition was on many levels—screen performance, tradition versus modernity, and conflict between the past and the future. Bachchan played the strict principal of a school called Gurukul who believed in honour, tradition and discipline, while Shah Rukh was a progressive music teacher who believed in love. The film’s dialogue articulated the music teacher’s worldview: “Duniya mein kitni hain nafratein...phir bhi dilon mein hai chaahatein...jao kehdo is jahaan se, is zameen se, aasman se...rok na sakenge ab yeh mohabbatein. (There is so much hatred in the world, yet so much love in the heart. Tell the world, the earth, the sky, love cannot be stopped.)”

On and off-screen, the clash was squarely between the Angry Young Man of the 1970s and the New Age Man of the 1990s. The Angry Young Man had not aged well, it seemed, with his ambitious plans to corporatise film production under the banner of ABCL having come a cropper. It left Bachchan so broke that, by his own admission, he had to go to see Yash Chopra for work. In contrast, the New Age Man had just taken a chance on the idea of corporatisation, setting up a studio called Dreamz Unlimited with his friends, director Aziz Mirza and actress Juhi Chawla. Phir Bhi Dil Hai Hindustani, their first film, would be released in the first month of the new millennium.

There were other neat parallels. Salim-Javed and Yash Chopra were the men who did the most to craft the Angry Young Man image with Deewar (1975), Trishul (1978) and Kaala Patthar (1979). Chopra took a chance on the young Shah Rukh to give him the part in Darr that consolidated his stardom. His son Aditya Chopra added to Shah Rukh’s aura by casting him in what became the iconic role of Raj in DDLJ.

AAMIR’S TURNING POINT: Lagaan transformed the way Aamir worked and its global success gave him the sheen of a marketing genius he carries to this day

THE SCREENING OF Asoka in Toronto was to have been Shah Rukh Khan’s big debut on the global stage. Sivan had first suggested the idea of the film to Shah Rukh when they were both atop a train, shooting the iconic ‘Chhaiyyan Chhaiyyan’ song for Mani Ratnam’s Dil Se in 1998. Now, in 2001, their film was almost on its way to being shown to film-goers and international critics in Toronto. For the occasion, Shah Rukh, had travelled to New York with co-star Kareena Kapoor and Karan Johar’s mother, Hiroo. But 9/11 stopped the world in its tracks and the Asoka team had to stay on in New York. Shah Rukh returned to India without screening the film in Toronto. And Lagaan stole a march on Asoka. It had released to a rapturous response in India in June 2001 and was chosen to represent India at the Oscars.

Thanks to a sustained campaign by its lead star and producer, Aamir Khan, Lagaan would end up in the shortlist of “Best Foreign Language Film”. Aamir knew that getting noticed by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences—and being picked among the final five—would not be easy. But he is a methodical man and went about the film’s promotion systematically. He got one of the earliest enthusiasts of the film, director Roland Joffé, to recommend it to his friends. Parmeshwar Godrej called her well-placed pals, Steven Spielberg, Richard Gere and Ismail Merchant. Mira Nair, whose Salaam Bombay! had been nominated in the same category in 1988, wrote to “friends who are Academy members to see Lagaan and vote for it”. Aamir himself did a series of interviews in the US with USA Today, Variety and Hollywood Reporter, among others; and the film’s US distributor Sony Pictures Classics issued full-page colour ads in publications such as Variety and Hollywood Reporter.

Finally, on March 24th, 2002, Aamir, who had spent over two months in Los Angeles promoting the film, after it had been bought by Sony Pictures Classic, walked the red carpet of the Kodak Theatre in downtown Los Angeles with wife Reena Dutta and director Ashutosh Gowariker and his wife Sunita. The sports epic he had made was really a film about national honour and Indian pride. It was not only about defeating the colonial rulers at their own game, cricket, but also about trying to storm the bastion of global storytelling with a three-hour-forty-minute drama. Though the movie was replete with song-and-dance, the director refused to edit it or remove any musical scenes so that the film would be more compatible with the Academy’s sensibilities. It was felt that the West, having lost its love for the musical, was not that keen on seeing songs pop up in other cinema traditions. This has always been, and to some extent still is, the obstacle for popular Indian cinema in the West.

SALMAN’S BIG FIGHT: They were close once but then one night an ugly rupture pushed both Salman and Shah Rukh to breaking point

THERE HAD BEEN bad blood between Shah Rukh and Salman since the time Salman had disrupted the Chalte Chalte shoot. But when common friend Farah Khan got married in 2004 to Main Hoon Na’s editor, Shirish Kunder, the two men had an emotional reunion at one of the wedding functions. Salman even made an appearance with Katrina Kaif as a gesture of friendship in the grand finale of Kaun Banega Crorepati (Season 3), hosted by Shah Rukh. But the truce didn’t last long and in July 2008, the two stars almost came to blows at a party at Mumbai’s swish Olive restaurant where Katrina Kaif was celebrating her birthday. Old resentments had surfaced—about Aishwarya Rai, and about Shah Rukh not reciprocating Salman’s cameo in the Om Shanti Om song with a cameo in Salman’s Main Aurr Mrs Khanna (2009), produced by his brother Sohail Khan and Ronnie Screwvala. Later, in a 2010 interview, Shah Rukh said: “Sometimes two people run parallelly to each other and parallels don’t meet. We don’t have any common ground. I’ve spent some really good times with him and his family has been really kind to me and I know deep inside my heart he will never wish me ill.” Salman wrote in a blog in 2008: “Main sher hoon aur koi bandar sher ka shikaar nahi kar sakta (I am a tiger and no monkey can hunt me).” In 2014, he said in an interview: “He thinks my thinking is wrong, I think his thinking is wrong. I’m hurt, I’ve always loved Shah Rukh as a younger brother. I’ve shared an amazing time with Shah Rukh.”

At the core of the 2008 fight was a proposal by Salman that the three Khans, who were seated at one table at Katrina’s party, do a stage show for charity. Trouble began when Shah Rukh hesitated. Salman then launched into a rant about how much his family had done for Shah Rukh when he began in the industry and how Shah Rukh had always undermined his intelligence. Many ugly things were said by both that evening but the deal-breaker came with Salman saying Shah Rukh was not capable of even being called a man, to which the latter retaliated: “Why don’t you ask your ex about it?” That was it.

Karan Johar and Gauri Khan were called to help and Gauri had to pull Shah Rukh out of the restaurant. Pictures from that day show her virtually dragging Shah Rukh to the car, as a weeping Katrina emerged at the entrance with an enraged Salman. The next evening, after a sleepless night that left both Katrina and Salman agitated, the latter went to his farmhouse in Panvel. Over a three-hour conversation frequently interrupted because of poor connectivity, he vowed to a close friend how he would show Shah Rukh his place in the industry. “He thinks I am an ass. You wait, I will finish him.”

Words spoken in anger but somewhat prophetic, given that Shah Rukh has always known he may be a bigger star globally but Salman is beloved as the eternal ‘bhai’ in the domestic market.

This was an echo, if the December 1991 issue of Stardust is to be believed, of Salman’s behaviour after the unexpected success of Maine Pyaar Kiya at the beginning of his career: “Two years ago, he was a gawky, gum-chewing, pint-sized young boy” who hoped to one day show his “smilingly sarcastic father” and his “supercilious girlfriend” Sangeeta Bijlani that he was “not an idle layabout, that he could stand on his own two little feet”. It talked about how Salman had been transformed by the illusion of fame, showing hitherto unseen traits of “arrogance, ruthlessness, indifference, intolerable conceit”. The article talks of his long string of affairs, his “way of getting back at Bijlani for all the humiliation she had heaped on him in his underdog days”.

The article said that when Salman had told his father he wanted to be an actor, the ace scriptwriter let out a hoot of laughter. “Have you seen your face in the mirror?” it quoted Salim Khan as saying. “You can never become an actor so please don’t embarrass your family by making your ambition public.” The article stated that Salman hated his father for that remark. Indeed, he had hated him all his life. Don’t you be deceived by the happy façade put up by the ménage-à-trois, wrote Stardust, adding, “Salman has never forgiven his father for bringing Helen into the family. Yet today father and son are the best of buddies.”

His relationship with Shah Rukh had the same love-hate quality. The contrasting reactions to their stints on TV highlighted their other differences. After Kaun Banega Crorepati, Shah Rukh hosted the only season of Kya Aap Paanchvi Pass Se Tez Hai? for Star Plus in 2008. Sony, meanwhile, convinced Salman Khan to host 10 Ka Dum, which the actor believes began his journey back to stardom.

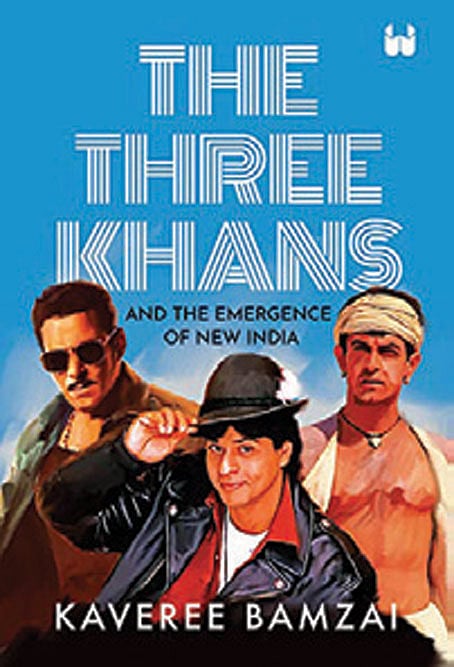

(This is an edited excerpt from The Three Khans: And the Emergence of New India by Kaveree Bamzai)