Kandahar 1999: Story of a Hijacking

The first-person narrative recalls the drama that kept India awake for seven fateful nights

Manvendra Singh

Manvendra Singh

Manvendra Singh

Manvendra Singh

|

20 Dec, 2019

|

20 Dec, 2019

/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Landahar1.jpg)

(Illustration: Saurabh Singh)

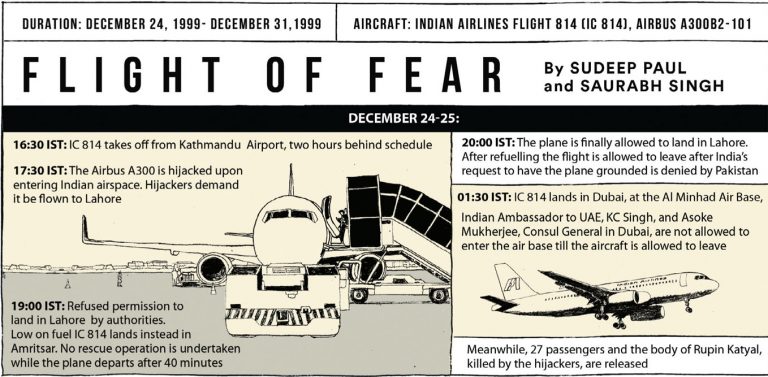

Almost a decade before the Mumbai attacks of November 2008 and a couple of years before the Parliament attack of December 13th, 2001, the Kandahar hijack was a watershed in India’s fight against terrorism. Indian Airlines Flight 814 took off from Kathmandu on December 24th, 1999, and was taken over by terrorists soon after entering Indian airspace. The aircraft ended up in Kandahar after touching down in Amritsar, Lahore and Dubai. Twenty years later, we are still taking stock of what happened and debating what could have happened. To bring home the hostages, one of whom succumbed to his injuries sustained at the hands of the hijackers, New Delhi released three terrorists. Two of them would earn notoriety soon enough. The crisis lasted a full week under the watchful eyes of the Taliban till December 31st. This first-person narrative recalls the drama that kept India awake for seven fateful nights

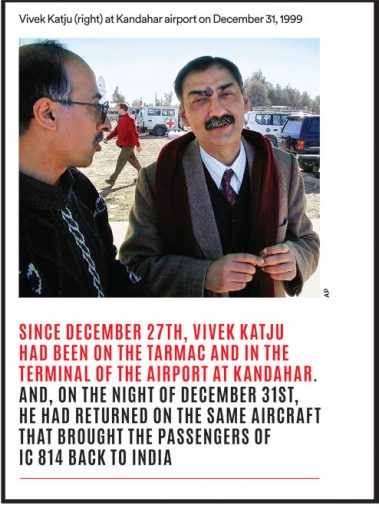

YES, IT WERE his eyes that caught my attention on that cold December night. It wasn’t the colour, for I still can’t recall what it was. It was the expression they carried which struck me the moment I saw him deplane, quietly, and head away from the crowds swirling outside the then ceremonial lounge at Delhi’s airport. He was walking away without exchanging words with anyone when I first saw him. I was standing, waiting, in the lounge, at the limits permitted to me. As he neared, it was the message in the eyes that hit me, and the hug that followed was warm, genuine, but unusual. Vivek Katju was not known to be a jhappi chappi type, quite the opposite, in fact, reserved, matter of fact and a man of few, but sufficient, words. He looked at me, but his eyes went through, beyond the wall into the darkness, and far away into the distant horizon.

His eyes looked vacant, possibly even glazed. They were there but could have been anywhere, as though he’d seen an apparition. In reality, since December 27th, he had been on the tarmac and in the terminal of the airport at Kandahar, Afghanistan. As joint secretary for Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan in the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), he had gone as part of India’s negotiating team to Kandahar. And now, on the night of December 31st, 1999, he had returned on the same aircraft that brought the passengers of IC 814 back to India, and to freedom.

In my muddled state of excitement, relief, pain, I blurted the most inane of questions, and his look returned. “Vivek, what was it like?” There was a flash in his eyes, maybe of anger, and I felt a pang of guilt, a feeling of silliness spread. He looked at me, through, glazed, and said, “Manvendra, how do you talk to someone whose benchmarks are not in your century?” And then he looked away, hurt. We walked further into the ceremonial lounge until an explosion of flashbulbs caught my attention, and I noticed it was the recently married, and widowed, late Rupin Katyal’s wife walking down the aircraft steps. I said “Let me condole with her” and moved to head out when he grabbed my arm, tightly, and said softly, “No, don’t, as she doesn’t know yet.”

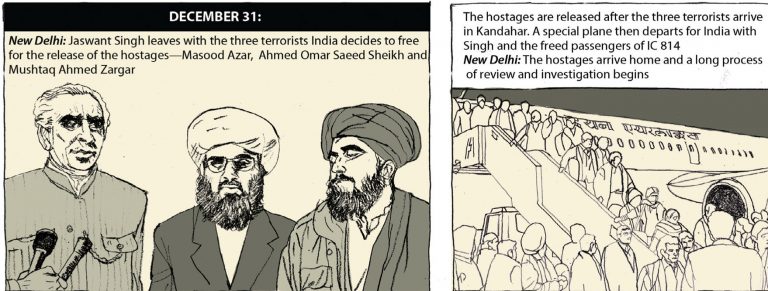

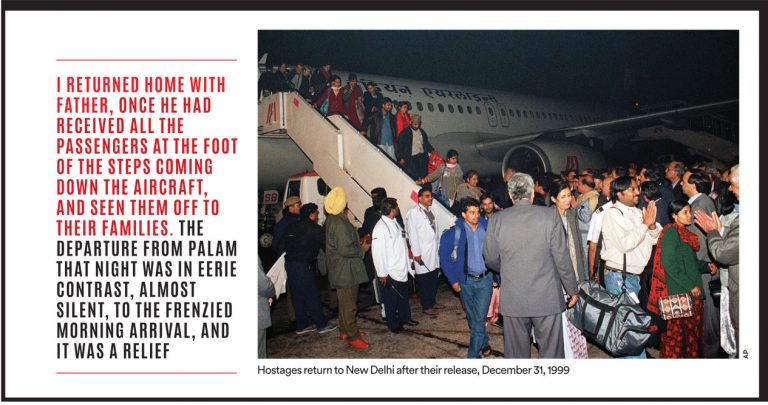

I returned home with father, Jaswant Singh, once he had received all the passengers at the foot of the steps coming down the aircraft, and seen them off to their families. We returned home the way we had arrived in the morning, from the Technical Area of Palam airport. I had first entered the Technical Area on a bleak September morning in 1995, to load the body of Captain Arun S Jasrotia into an Indian Air Force Dornier. He was to become the first in my life circle to be awarded a posthumous Ashok Chakra, and alas, wasn’t the last. Subsequently, I had been into the Technical Area numerous times on journalist assignments, but nothing was like it was in the morning of December 31st, 1999 when father’s car approached the gate swarming with television cameras and other media. The Air Force Police and their civilian counterparts had a difficult time getting the car through that gate. The departure from Palam that night was in eerie contrast, almost silent, to the frenzied morning arrival, and it was a relief to have father back at home.

As the logs burned in the fireplace, father remained glued to the cordless phone, answering endless calls, mostly of relief, and some even accusatory. That was to remain the theme for years on end, and had to be taken as par for the course. Midnight brought on the new year, millennium too, and his first undisturbed sleep in about a week. The doorbell rang as the first light of the new millennium broke over the city. When I opened the door, an enormous bouquet of flowers hung in the air between me and a lady with a wide smile. A few steps behind stood a man, quietly, looking clean, and relieved. I ushered her in after she asked for father, while the man followed without uttering a word. When father walked in, she was effusive in expressing her gratitude, exhibiting sincerity, and all the while adding numerous apologies. For she was the wife of the co-pilot of IC 814 and we finally got to put a face to a voice heard every night. From the time the Airbus A300 reached Kandahar, she had made it a point to call every midnight, or after, crying and cajoling father to do something to get her husband back to India and safety. Months later, when I recounted this to a joint secretary friend of mine at the MEA, he exclaimed, “What do you mean, boss doesn’t have anyone at night to answer the calls? There is no reason not to have somebody on phone duty.” The MEA then began to depute phone attendants at night, finally. The joint secretary friend is now in high places.

The flowers brought to close an unforgettable chapter that began a week earlier on the steps of Holy Angels Hospital in Vasant Vihar, New Delhi, when I returned from home carrying some essentials for my daughter, born barely an hour back. Father was to have arrived in my absence and performed the Rajasthani practice of giving a newborn her first taste of sweet. It was Christmas Eve and he was meant to call it a day from work and join the family in celebrating the arrival of the baby girl. Alas, it wasn’t to be, for I bumped into him on the steps of the hospital, and surprised, I asked: “You’re leaving so soon?” He looked up into the sky, tense, and said, “An aircraft from Kathmandu has been hijacked, it’s in the air and we don’t know where it is headed.” That was all he said before he was driven away. Celebrations of the birth were never going to be the same again, at least not until the drama was over, and with the destination of the aircraft unknown, when that would happen was up in the air, in every sense.

Amritsar airport on a cold December night can be a miserable damp place, but ideal for stalling an aircraft in the dew-soaked grass. That, however, was not to be, and with a constantly moving aircraft, any chance of interventionist action was impossible. Once IC 814 took off from Amritsar, India lost its only opportunity at securing the passengers and aircraft from the hijackers. There has been much speculation. But suffice it to say Amritsar was the first operationally appropriate locale but the opportunity didn’t come to pass. Dubai provided the next opportunity but the person who controlled the air in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) wouldn’t give permission, as he wouldn’t for another more basic human purpose. So when the aircraft took off for Lahore, the fate of the passengers was sealed and India’s room for manoeuvre severely restricted.

MY DEAR boy, where do you think this plane will go?” the voice asked over the international line. The baritone sound was unmistakable to Asoke Mukerji, India’s Consul General in Dubai, when he received the call at 1830 local time. This was a more Anglicised version of the question Vivek Katju had asked his MEA colleague Talmiz Ahmed, joint secretary for West Asia and North Africa, a little while earlier in Delhi. Nobody had a clear idea until the plane appeared to be nearing the Gulf area, and then KC Singh, India’s Ambassador to the UAE, worked on his personal contacts to get clearance for the aircraft to land in Dubai. The UAE authorities wouldn’t let it land at the international airport as it was chock-a-block with flights on account of the Christmas rush. After much cajoling, the UAE Commander of the Air Force and Air Defence, Mohammed bin Zayed al-Nahyan, allowed IC 814 to land at Al Minhad air base, about 25 km south of Dubai. MBZ, as he’s colloquially called, is now high on the global diplomatic index.

The Indian consulate in Dubai, incidentally, had developed a protocol for hijackings since 1984, for IC 421 had been hijacked to Lahore, then Karachi and finally to Dubai. The pro-Khalistani youths had bet on being granted asylum in the US, and when that was not a possibility, they relented and freed all the passengers, amongst whom was the celebrated Indian strategist and then director of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis, the late K Subrahmanyam, father of the current External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar. IC 421 had been hijacked with knives and make-believe explosives, and it wasn’t until it reached Lahore that a weapon was seen by the passengers: “It came as a great surprise for us to suddenly see a weapon surfacing after we left Lahore.” Two British nationals on board the ill-fated flight, Mr and Mrs Dominic Barkley, say they saw the Pakistani authorities hand over a parcel to the hijackers and it was from the same parcel that the revolver was produced. Said Barkley: “I saw one of the hijackers get down from the aircraft at Lahore and collect a paper-wrapped packet. He came aboard soon after and pulled out a pistol from the packet.” (India Today, September 15th, 1984). Dubai on December 24th, 1999, was to provide a similar twist in the tale, but there was more drama before that happened.

The Dubai-Al Ain Expressway exits on to Umm Nahad Street, a little after Tijarah town. But at 2130, it was before the exit that a car flying the Indian Tricolour came to a halt, as armed guards blocked its way. “Safir-e-Hind?” asked one of them, Arabic for ‘Ambassador of India’, whilst peering into the cabin. KC Singh, India’s Ambassador, and Asoke Mukerji, Consul General, Dubai, were the passengers, but the UAE authorities had decided to bar their way to the Al Minhad air base and IC 814 that had landed. Other cars sped by while the Indian diplomats struggled to get permission to proceed from the UAE authorities, who are now high on the Government of India’s feted list. As the hours ticked and temperatures dropped in the cold desert night, battery power in the mobile phones fell proportionally. By the time Dubai clocks struck midnight into Christmas, the mobiles had lost almost all power. After 0100, they were of no use, and India’s two senior diplomats in the UAE were now completely out of communication. The wait continued under the desert stars, lonely and quiet. Mukerji remembers the stillness being shattered at about 0345 or 0400 when a group of SUVs came speeding from the Al Ain direction. They had blackened glasses, he remembered, and they weren’t stopped from proceeding to Al Minhad air base. Incidentally, Mohammed bin Zayed was born in the Trucial State of Al Ain.

At about 0510 or 0515, one of the armed guards walked up to the official Indian car and said permission had been given to proceed to Al Minhad air base. By the time the car entered Al Minhad, the Emirati officials there had begun the Fajr prayer, the first of the day. Mukerji recalls that Brigadier Sharafuddin Al Sayed Sharaf, deputy head of Dubai Police, was the only one wearing a red-and-white chequered kaffiyeh. The Gulf region has a vast population of Arabs displaced from Iran in the early years of the 20th century. The Iranian-Arabs, as they are known, are from a trading rather than Bedouin background. As one of them, Sharaf knows transactional relationships better than most. He was also the only one who looked up from his prayer position at the sound and sight of IC 814 lifting off into the sky, landing gear still visible. Indian diplomats were allowed in after IC 814 had been given permission to depart.

After the prayer, Sharaf informed the two officials that the hijackers had released some elderly and ailing passengers, “and thrown a body”. “As Consul General, you have to identify the body,” he told Mukerji. It was during the initial debriefing that a released passenger said that weapons came on board IC 814 at 0430. “We didn’t see any before that,” he told the Indian officials, echoing words of the British passengers from IC 421 in 1984, and the Lahore twist. Dubai had provided a repeat of that tale.

When Asoke Mukerji got home later to freshen up and complain to his wife that they had not been allowed anywhere within eyeshot of IC 814, she exclaimed that she’d seen it all night on CNN which had a live telecast from Al Minhad air base. Mohammed bin Zayed’s younger brother, Abdullah bin Zayed al-Nahyan, was then the minister of information and culture. So while the elder brother had not allowed Indian officials anywhere near IC 814, and denied Delhi permission to mount a rescue operation, the younger one had given CNN access to broadcast the hostage aircraft live. An Indian Air Force IL-76 had been loaded with a hit team from 52 Special Action Group (National Security Guard) to undertake the rescue mission, but permission was denied by the UAE authorities. Years into the next millennium, Mohammed bin Zayed was to visit India as Chief Guest for the 68th Republic Day celebrations on January 26th, 2017, and the younger is now the minister of foreign affairs and international cooperation of the UAE.

Even as the aircraft was in the air, and with New Delhi not in contact to know where it was headed, India first learnt the destination of IC 814 from the most unlikely of sources—on the ground, in Dubai, from an Afghan national. The manager of Ariana Afghan Airlines had made endless requests to India’s consulate for a visa, and New Delhi had firmly kept its door shut on him. It was the same manager, with unrequited visa requests, who asked Mukerji: “Do you know where the aircraft is going?” When he heard a negative response on the other side of the phone line, he said, “I’ll tell you, it is going to Kandahar.”

Kandahar under the brutal Taliban was never a desired destination for anyone but those who are jihad-inclined. So when IC 814 landed in Kandahar on the morning of Christmas, there couldn’t have been a greater irony or worse fate for the passengers and crew. They were, after all, in the grip of those whose benchmarks were not in the current century, as Vivek Katju succinctly described. Isolated from civilisation, IC 814, its crew and passengers, would be the focus of a drama centred on Kandahar. And aspects of that drama were to be enacted in New Delhi as well, as it had geared up to welcome the new millennium.

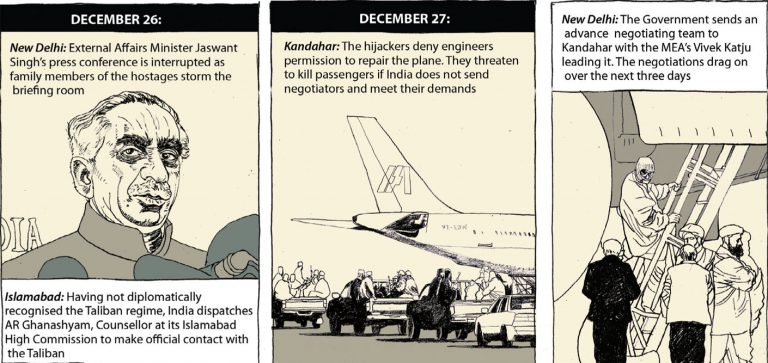

The first time I saw father in a bad frame during this period was on December 26th. As the nation clamoured to know more, and some bayed for blood, the MEA conducted its first press briefing with father presenting the picture. Within a few minutes of the briefing, there was a ruckus as family members of the IC 814 passengers stormed the room, shouted slogans and demanded that their relatives be brought back unharmed. In such a situation, it would be the demand of any family member, but it was the first time an official briefing was disrupted, whilst also exerting pressure on the Government. That day was also the first time the Government of India officially made contact with the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. It was not a regime India had recognised, having played on the opposite side during the civil war in Afghanistan.

The newspapers next morning gave more prominence to the press conference and the disruption, naturally, but I did find a small mention of a counsellor at the Indian High Commission at Islamabad having reached Kandahar for the sake of the passengers to initiate discussions with the Taliban regime. When I read the name of the counsellor, I was transported back in time, space, geography and language.

In the winter of 1986-1987, I had made my way to Damascus, Syria, for fieldwork on Palestinian refugees. It was not usual, and the family was naturally concerned. So I’d promised them to keep in touch with the Indian embassy in Damascus, which is where I met a wonderful diplomat couple. Ruchi and AR Ghanashyam were third secretaries in the embassy and were completing their advanced Arabic language course. My guide at college had merely given me the name of a Syrian professor, with the words that “He will help you get in touch with the refugees.” So when Ghanashyam asked me if I needed any help, I said, “I’m looking for Sadiq al-’Azm but don’t know where to find him.” He was a big name in academic circles and Ghanashyam helped find him at the University of Damascus as Professor of Modern European Philosophy. He was from a very posh Levant family, and married into one too.

Sadiq al-’Azm (1934-2016) was as surprised to see me as the Indian embassy had been. And he was as warm and helpful as the diplomats, even sharing a copy of his famous article, ‘Orientalism and Orientalism in Reverse’, a critique of Edward Said’s Orientalism. “Edward doesn’t talk to me after this article,” he added with a smile. He was of great help in guiding me to the right refugee contacts and shared a brilliant story about his wife’s bus journey from Damascus to Varanasi. All of which I recounted to Ruchi and Ghanashyam over the only Indian meals I was to have in Syria. Before leaving, I had gone to thank them when Ghanashyam asked if there was anything else I needed. I shared my dream with him, to view Damascus from the top of Jabbal Qassioun. In Seven Pillars of Wisdom, TE Lawrence had described it to be ‘like a pearl in the morning sun’. I wanted to see for myself if it matched the description. Ghanashyam drove me there, and the sight was as breathtaking as described.

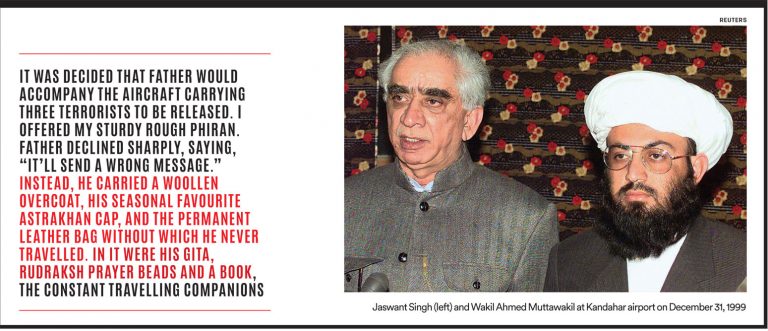

AR Ghanashyam, Counsellor, Indian High Commission, Islamabad, was the first to make official contact with the Taliban. And until a Pushto translator arrived from Quetta, the opening conversation with the Taliban was conducted in Arabic. The Taliban government was represented by its young Foreign Minister Wakil Ahmed Muttawakil. He stayed put in Kandahar almost throughout the hijacking period, a public face to the world for the mysterious Taliban leadership. Ghanashyam remained in Kandahar to arrange logistics support for a larger Indian delegation that would be arriving to handle matters. On December 27th, an Indian Airlines A320 landed at Kandahar carrying a composite negotiating team, and it included medical as well technical personnel. More than two days on the ground in Kandahar had depleted its batteries and as a result passengers and crew were in darkness. The overflowing toilets had to be serviced as well since the smell was intolerable.

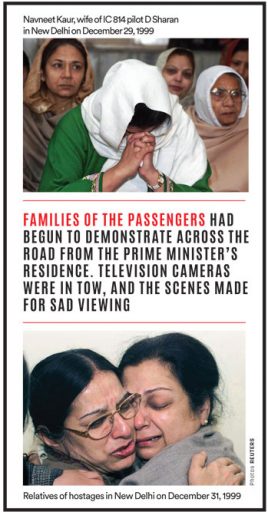

Vivek Katju was the MEA representative and recalled years later how, back in Delhi, my mother would call his wife, Geeta, to offer her a shoulder if it was required and keep the morale high. This was not the case with the families of the passengers who had begun to demonstrate regularly across the road from the Prime Minister’s residence. Television cameras were in tow, and the scenes made for sad viewing during the evening news wrap. It was also the tenor of the midnight calls that father would receive from the lady whose husband was a crew member. Her calls came to be echoed by a visitor who began to frequent home and harass my mother.

Since she was known to the family, her visits were always unannounced, unsolicited and always unpleasant. She had a close relative on the flight and had been asked by her in-laws to exert pressure. It is unlikely she knew about the midnight calls since none at home mentioned them to anyone, but the visitor maintained the same pitch. “So what? Release the bloody terrorists, get the passengers back safely,” and so on. This went on for days, and since no deal seemed to be in the offing, she blurted one day, “So, is he [father] going to let the passengers die?” I lost it one day overhearing her say, “These terrorists can always be caught again.” I walked up to her and asked, “Do you know how many ambushes have to be placed every night to get one contact with militants? How many houses have to be searched every day, how many area domination patrols have to go out in every weather?” etcetera. It didn’t phase her one bit.

IN COLD and bleak Kandahar, conditions were hardly better. Key members of the negotiating team were housed in a guest room at the airport, unused to sharing rooms back in India, but unwilling to fuss about it in such a crisis. Another room served as the dining room, used twice a day to consume the naan and dried meat that served as meals. The medical and technical teams were accommodated separately, tasked for a very different objective. The main objective though remained the release of the passengers. At this stage of the crisis, the Taliban in Kandahar had maintained a reasonable and friendly veneer towards the Indian officials handling negotiations. Movement was not overtly restricted and there wasn’t even a hostile presence in and around IC 814 on the ground. All that was to change when an Indian official on the negotiating team tried to test the Taliban, in keeping with the friendly banter that had existed thus far.

“Since you’ve been so kind and friendly towards India, why don’t you let us do a rescue operation?” Sparks flew, and the Taliban official prepared to leave in a huff, but before doing so, retorted, “What? Let you spill Muslim blood in Afghanistan?” He left to report this exchange to Taliban’s Kandahar Corps Commander and the airport was not the same after that. Taliban Special Forces and other rag-tag armed cadre swarmed all over Kandahar airport and surrounded IC 814. They wouldn’t leave their positions until the deal was sealed but that was still a long way off.

India could only have mounted a rescue operation in Kandahar had Pakistan allowed its airspace to be used, including for Indian Air Force combat aircraft. For without securing the airspace, no Indian assault team could have managed to enter Kandahar airport, conduct an operation and exit with the passengers and the hijacked IC 814. A Pakistan bruised and bloodied by the Kargil defeat a few months earlier, recently taken over by an army coup, would be the last country to ease matters for India. An entry and exit through Iranian or Central Asian airspace was possible but would still require combat air cover, probably even more so, thus making the plan unrealistic. But this test was enough to make the Pakistani presence overt, state and non-state.

Unknown to most, some Indian units had opted for an ingenious communication tool during the Kargil conflict. As field radios were easily broken into, and line communications vulnerable to terrain stresses, there were some who used an international satellite phone service to communicate. Pakistan was not known to have the technological knowhow to listen in on an Iridium call. In fact, my late friend, Major Sudhir Walia, also an Ashok Chakra recipient, had called me from an Iridium phone after winning a peak in the Kargil sector. And Iridium phones once again came into use in Kandahar as the Indian negotiating team communicated with New Delhi in as much secrecy as was possible.

AS THE situation unfolded in Kandahar, and negotiations dragged on, it became clear that there would be an exchange of terrorists for the passengers. The country was, obviously, gripped with a debate on that issue. National prestige was an oft-repeated sermon, and in the midst of all these television discussions, Israel came to feature most prominently. How that tiny country tackled terrorism, not buckling under pressure, not compromising, was for all to see. That image persists till this day in India, and Israel continues to the regarded as the benchmark. The reality, however, is far more complex as Israel values the lives of its citizens above all else and is willing to go any length to achieve its national objective, the return of its citizens, alive, or even with their remains. This has not been without controversy in Israel, most notable being the 2008 release of Samir al-Quntar, a Lebanese convicted for the 1979 attack in Nahariya, in which he bludgeoned a four-year-old girl. Gilad Shalit, a tank gunner was captured by the militant group Hamas in 2006, and exchanged in 2011 for the release of 1,027 Palestinian prisoners held by Israel. India found itself similarly boxed in, and as is known, agreed to exchange terrorists for 160 passengers and crew remaining in IC 814.

As with all negotiations, demands begin from a maximalist position, and then are whittled away to a minimum acceptable figure by those who have to give in. It is the trick in all such negotiations. So the hijackers began by asking for 30-odd terrorists to be freed, all the while keeping their core interests in mind. The Government became aware of the core list as time went by and negotiations continued. Joining the dots from earlier incidents led to the identification of the central list.

In July 1995, as with all defence correspondents in Delhi, I too was covering a most unlikely kidnapping in Kashmir. Six foreign nationals trekking in Liddarwat area in Pahalgam, Anantnag district, were picked up by a group that called itself Al-Faran, a name previously unseen on the terrorism radar. My reporting attracted the attention of a Major General at Army headquarters who shared a paper with me which explained the genetics of Al-Faran. It was simply a front organisation for Harkat ul-Ansar, which itself had been formed by the merger of Harkat ul Jihad al-Islami and Harkat ul-Mujahideen. In early 1994, Harktat ul-Ansar had sent a Pakistani cleric on a fake Portuguese passport to Kashmir and his task was so resolve the differences between the two feuding factions. He was arrested in Khanabal near Anantnag, and sang like a canary when interrogated, admitting his real name was Maulana Masood Azhar. Al-Faran demanded the release of terrorists held in custody, and his name topped the list. And the former Pakistani Interior Minister Major General Nasrullah Babar had even written a number of letters to the Government of India pleading for the release of Masood Azhar.

Omar Sheikh, the London-born, private school-educated terrorist, once described by a classmate as ‘dysfunctional’, had been arrested in 1994 for the kidnapping of four Western tourists. His family connections in Pakistan’s administrative circles ensured that the name featured in the central list. Mushtaq Zargar, or Mushtaq Latram, as he is called colloquially, wasn’t making the cut until someone in Pakistan realised there was no Kashmiri name in the list. He made the list to ensure Kashmiri tokenism.

As the to-and-fro negotiations continued between Kandahar and New Delhi, a pattern set in at the airport. And after tensions had risen following the ‘test’ and Taliban deployment, matters had eased enough for conversations to resume. As is wont in this part of the world, conversations aren’t shackled by national boundaries. In the limited space allowed for walks, an Indian negotiator and a Taliban guard struck up a conversation. They would continue their small talk whenever opportunity arose. When the Indian official asked him where he was from, he replied without hesitation, Pakistan. “What do you do?” “I fire anything from a rifle to a machine gun and an anti-tank rocket also,” he replied. “How much do you get paid?” “I get a bus fare from my village to here, twice a year.” After the chit-chat, the Indian official asked, “Who looks after them [his family] while you’re here?” Once again, he didn’t hesitate: “Allah takes care of my family.”

Once the final details of exchange were worked out, the release list completed, the last piece of the jigsaw still needed to be put in place. Who would seal the deal from India’s side? There has been much speculation about this decision, and until the personal diaries and Government records are made public, it will remain in those realms of hypothesising. My father did tell his closest policy confidant that he “felt the burden of expectation.” He had promised his confidant that everything would be shared, but that won’t happen on account of the 2014 accident. So it was decided that on December 31st father would accompany the aircraft carrying three terrorists to be released. That morning, the gloom at home was as grey as the day outside. Not knowing what else to say, I offered my sturdy rough phiran, a peasant rather than an emporium purchase. Father declined sharply, saying, “It’ll send a wrong message.” Instead, he carried a woollen overcoat, his seasonal favourite Astrakhan cap, and the permanent leather bag without which he never travelled. In it were his Gita, rudraksh prayer beads and a book, the constant travelling companions.

Postscript: In April 2002, Vivek Katju returned to Kandahar airport, as the visiting Indian Ambassador to Afghanistan that had been freed from the tyranny of the Taliban. The Indian mission had been reopened, and as the Joint Secretary who had seen the most tumultuous period of India’s relations with Afghanistan and Pakistan. Father had selected him to be the first ambassador in a new era. He recalls entering a room at the airport to find two US soldiers recovering from their battle wounds. It was being used as a medical infirmary room where the wounded were treated. When they asked him what he was doing inside, he told them the story, and that he was visiting the room because it had served as India’s dining room whilst negotiating the release of the IC-814 passengers.

Years later, I was asked to be part of a panel discussion on hijackings and hostages by NDTV. In the studio audience were two IC 814 passengers, a man with a stoic expression and a lady with strong opinions. She was expansive with her views, and always interjecting. During the discussion, she declared that the Government had been very wrong to release the terrorists in exchange for the passengers. I mumbled some incoherent response to her statement. Later that evening while watching the broadcast of the show, father exclaimed, “She was the most hysterical of the passengers.” He left it there, and many more years later, I learnt that when father entered the aircraft after it was released by the hijackers, the same lady had screamed, then lunged at him, pounded his chest and said, “What took you so long?”

/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Cover-AfterPahalgam.jpg)

More Columns

Pakistan Launches Another Wave of Attacks on India Open

Major Escalation by Pakistan Open

India hits Rawalpindi, seat of Pak Army HQ, after foiling attacks targeting our cities Open