When the Hills Had Eyes

A two-year-long rebellion that shook the ghats of Andhra Pradesh. A pious plainsman who turned revolutionary to lead native tribes against an unjust administration. Ninety-four years later, a search for the legacy of Alluri Sitarama Raju and his lieutenants Gam Gantam Dora and Gam Mallu Dora

/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Whenthehills1.jpg)

‘To be a hero in undiscovered territories is to be obscure; these territories and their songs are lit only by the most anonymous blood and by flowers whose name nobody knows’

—Pablo Neruda

NEARLY A CENTURY ago, the low hills of northeastern Andhra Pradesh were aflame with revolution. The ‘fituri’, as the British dubbed it, was rather randomly christened the ‘Rampa disturbances’ after a taluk in the hilly belt, although the epicentre was Gudem, an inaccessible block of about 1,865 square km where the conditions were ripe for rebellion. Today, it is hard to imagine these forests, in full monsoon livery, ringing with the crack of .303 rifles. A veil of historical obscurity hangs thick over the ghats of Visakhapatnam and East Godavari districts—the tribal ‘Agency’ areas that erupted in an early revolt against subjugation by colonial forces between 1922 and 1924. Here, the name Alluri Sitarama Raju, a self-styled healer and social reformer from the plains who became the unlikely architect of an organised resistance, is like a river whose mutinous course is etched into the land, a canyon deepening over time. Washed away in the weathering are the stories of dozens of unaccredited heroes who, exhausted by their struggle with want, nevertheless betook themselves to the forests for a severe contest with authority.

Chased by rainwinds on a dour, wet morning, we enter KD Peta, or Krishnadevipeta, a scrap of a town in Golugonda mandal, Visakhapatnam district, which is the gateway to Alluri country and the site of his grave on the banks of the Thandava. From here on, nearly every junction—in Nadimpalem, Rajavommangi, Makaram, Mampa—features the golden figure of a hermit with a flowing beard, a bow and a quiver full of arrows. The old police station building in KD Peta where Raju’s guerrillas tasted their second consecutive victory on August 23rd, 1922, is mostly intact, but presently out of bounds, stocked as it is with arms and ammunition. Raju would have been thrilled. The looting of Chintapalli, KD Peta and Rajavommangi police stations, in a carefully planned string of attacks that left the administration reeling and signalled the beginning of a sustained rebellion, had yielded enough weapons—26 muskets, 2,500 rounds of ammunition, scores of bayonets, swords and knives—that the guerrillas no longer felt defenceless. Today, a truck, seized with a thousand kilograms of ganja suspected to have originated at the border with Odisha, stands parked outside the KD Peta police compound. Locals still have a strained relationship with the law in these parts known for Maoist sympathies. “It is not safe for me to go out there alone, but you will be fine,” says S Ramesh, the young sub- inspector who recently assumed charge.

The hill people are affable enough, furnishing threadbare tributes to Alluri Sitarama Raju, drawn liberally from the 1974 Telugu feature film starring a histrionic G Krishna. The film, which made a popular hero out of Raju with Srirangam ‘SriSri’ Srinivasa Rao’s inspiring anthem ‘Telugu veera levara’ (Wake up, Telugu warrior), still plays to packed audiences when screened in Agency towns on festival nights. Of Raju’s two trusted lieutenants, the brothers Gam Gantam Dora and Gam Mallu Dora, who not only enlisted the support of locals and identified hideouts, but were likely the invisible strings tugging Raju towards the revolutionary road, precious little is known. “Gantam Dora is our god,” says Gam Bodu Dora, a small man of about 70, emerging from a circular hut in Lanka Veedhi, a hamlet in Battapanukula panchayat, Koyyuru mandal. A grandson of Gantam Dora, Bodu and his family live in poverty, subsisting on old-age pension of Rs 1,000 and four acres of land where they grow chillies, urad, red gram and other pulses he does not know the names of. “We do not remember him—he died soon after Raju in 1924, leaving behind a son and a daughter. But Mallu Dora died only in 1969, and he would tell us stories of the fituri. At the peak of the movement, it had been raining heavily, just as it is raining now, and the canals were swollen, but the brothers crossed a foaming stream—we call it Chedipigadda—near here without fearing for their lives. They knew greater dangers awaited them,” he says.

A Bagatha tribesman, Gantam Dora had been munsif of Battapanukula, a village in Makaram mutta (estate) perched at the lip of the forest to the north of KD Peta, but his lands were seized by A Bastian, the much-reviled deputy tehsildar of Gudem, citing alleged irregularities. Under colonial rule, muttadars who had earlier enjoyed the authority to collect and to levy taxes, were reduced to being agents of repression. An agrarian discontent had been brewing in the hills, both among peasants and muttadars , since the ban on podu cultivation— the sustainable practice of clearing small patches on the slopes for one-time cultivation, after which the land was allowed to be reclaimed by the forest—and restrictions on the gathering of forest produce. “Bastian behaved very cruelly and did so many wrongs to the people in this taluk that I do not find time to narrate them. He deprived me of my lands and gave them away to Sumarla Peddabbi. I begged him in so many ways not to ruin me. I sat at his feet on a particular day entreating him not to ruin me and he kicked me with his shoes, thrice. I was not given the entire portion of the land ordered to be delivered to me. I afterwards clung to the feet of Raju garu (sir) and I am determined to see the end,” Gantam Dora told British officials investigating the allegations of cruelty and venality against Bastian that were cited as one of the causes leading up to the fituri.

MALLU AKA MALLAYYA Dora, who took part in 58 encounters with the police, was captured at Nadimpalem on September 18th, 1923, convicted under Sections 121, 121A and 122 of the IPC and sentenced to death. His sentence was later commuted— he served a part of it at the Cellular Jail in the Andamans—and he was elected from Visakhapatnam to the first Lok Sabha. Even so, what we know of him today is something of an extrapolation from locals’ accounts of his cloak-and-dagger exploits. “He was fond of me,” says Gam Balamma, who was a companion to Mallu Dora’s wife and lived next door with the couple, who had no children. Balamma had fled an unhappy child marriage in Sarabhannapalem and found love in Lanka Veedhi with Bodu Dora, whom she married with Mallayya’s blessings. “Thatha (grandpa) had a booming voice and wore a white shirt, coat and dhoti. The only bus to town would sound its horn and wait for him as he took his time getting dressed. He was aggressive, never afraid to fight. A story goes that when he and Raju came upon a policeman striking a young mother, Mallayya put him over his shoulder and brought him here to give him a good thrashing, but they let him go only after serving him lunch,” says Balamma, shrivelled to the bone with age, as her elder daughter Daram Malleshwari, 35, helps her onto a string cot. The folds under her eyes ripple as Balamma unwinds the knots of her memories in her front yard amidst the pecking of chickens. “I spent 45 days in Delhi on the invitation of Indira Gandhi,” she says, clinging to the only instance when an Indian Government recognised the freedom fighter’s family. There may or may not have been a Coca- Cola drinking competition with Sanjiv Gandhi, and a gentle rebuke by Indira as a young Balamma innocently wandered off into Pandit Nehru’s quarters, but one cannot blame the family for reconfiguring the past on its own terms.

Much of history, in any case, is ruled by the imagination, even structured by it. For how else does one explain a pious plainsman’s rise as hero of the hillfolk? Alluri Srirama Raju—‘Sita’ was prefixed later, either in honour of his sister, or in an attempt to canonise him—was born in Pandrangi, Visakhapatnam district, on July 4th, 1897, to Suryanarayanamma and Alluri Venkata Rama Raju, of Mogallu, West Godavari district. Upon the death of his father, who ran a photography business from Rajahmundry, when he was 11, his uncle prevailed on him to continue his schooling, first from Kakinada and Visakhapatnam and later in Narsapuram, but he soon left home to pursue astrology, Sanskrit and native medicine at Tuni. Wandering the Agency wearing red khaddar, and dispensing herbal remedies and mantras, he came to be revered as a ‘devudu who had come to liberate them from the jubberdust rule of the British’, writes Atlury Murali, professor of history at the University of Hyderabad, in a 1984 research paper on Alluri Sitarama Raju and the Manyam Rebellion, 1922-1924. It must have been a staggering passage to self-discovery—an anchorite living off milk and fruits in a remote corner of Andhra finding, quite by accident, his calling as a revolutionary. Influenced by Mahatma Gandhi, he was nevertheless convinced that a violent denunciation of British policies was needed to liberate the natives. News of this strapping stranger and his plans to organise a rebellion reached the authorities early in 1922. When interrogated by the Agency Deputy Superintendent of Police at KD Peta on January 30th, Raju admitted that the people saw him as “a very holy man” and believed that he was going to start a fituri. “Everybody comes and asks me about it but most of them do not accept my denial. I cannot say whether the Non-Cooperation Movement is good or bad. I attended two meetings before of the Non-Cooperation Movement. I only asked the people here not to drink. I have not taught them non-cooperation,” he said, in a statement that is preserved in the Telangana state archives at Tarnaka, Hyderabad, a treasure trove of fituri files enclosing reports of local officials and muttadars on early rumours of Raju’s political activities, letters written in his own hand in Telugu and English, copies of non-bailable warrants issued to rebels, prosecution details and government notices informing the muttas of the new punitive policy towards rebel sympathisers.

“You must remember that Raju came from a traditional Kshatriya family. His mother was orthodox and short-tempered— she did not allow people from lower castes to enter their home. But he left at a young age, and for the rest of his life, remained a guest, visiting every couple of months or so,” says Alluri Satyavati, 50. Although, on some level, estranged from his community, Raju could never give up the cultural inhibitions he had grown up with, preferring for instance milk tinged with the thangedu flower (Senna auriculata) over the food of the tribals, and believing in the power of mantras to heal the body. The widow of Raju’s brother Satyanarayana Raju’s son Tirupati Raju, Satyavati lives with her three sons in a two-room house with unplastered walls. These are rented quarters but they are an improvement over their ancestral home across the street—an old hut with a straw roof that caved in this monsoon. A government school teacher, Satyanarayana Raju, upon retirement, had settled down at the place of his last posting—J Burugupudi, a village in Kirlampudi mandal, East Godavari district. “He died 26 years ago. My husband was a contractor and a small-time businessman, and after he died young, I took up tailoring to support the children,” says Satyavati, serving tea made in a makeshift kitchen in the shadow of a flight of stairs. One would think the Alluri family name was enough to assure a livelihood, if not a pension, in Independent India. “Growing up, we did not make a show of our identity. No one would have believed us anyway,” says Sri Rama Raju, 28, the eldest son who bears a striking resemblance to the photo of Raju with bullet wounds to the chest, provided by Bastian in the 1930s and published in 1971 by V Raghavaiah in his book on tribal revolts. Sri Rama Raju and his brothers Rama Raju and Laxman Varma, twins who are now 25 years of age, went to a missionary school for tribal children. Three years after their father’s death, the eldest brother dropped out of Class 8, unable to juggle studies and a job as a milk delivery boy making Rs 150 a month. “I learnt to drive the milk van, so I could make Rs 1,500 a month,” says Sri Rama Raju, who now drives a school van. Rama Raju and Laxman are halfway into their BTech courses, and moonlight as lab technicians to supplement the family income. For the first time, the family was invited to attend their Thathayya’s jayanti at the memorial in KD Peta this year—the moment of pride and awe they had waited for their entire lives. “Until ten years ago, no one even knew we existed. Actor Krishna was the only one to track us down, to present a panchaloha idol of Rama when the film was released. The rest of our family—Satyanarayana Raju’s four other children—is well settled in Hyderabad and Visakhapatnam. We had been allotted five acres of land, but because of a dispute with a local contractor who sabotaged my husband’s project—a tank bund—we suffered losses and had to take out a loan. We eventually sold off all the land to repay the loan and to pay for my only daughter’s wedding,” Satyavati says. Of late, she has been receiving invitations from neighbouring villages to unveil statues of Alluri Sitarama Raju and to participate in community events. It is rewarding to be recognised, she says, to be picked out in a crowd and summoned on stage. “For the government, though, we are as good as dead,” says Laxman Varma.

ACCORDING TO AN exhaustive report on the causes of the rebellion, submitted on April 21st, 1923, by AJ Happell, Officer Commanding Agency Operations, forced labour on the government’s road-laying projects, agrarian crisis and grievances of ex-village munsifs and ex-muttadars against Bastian had created a combustible environment in the Agency, jolting the tribesmen into action. Some of these rumbles echo through the hills even today. A British-era ghat road, opened to traffic in 1921, winds gently up to Lammasingi, a hill station wrapped in tattered quilts of vapour. Drive north, leaving the tourists behind, and you get a sense of falling off the map. There are no cellular towers in sight, just a strip of asphalt headed straight for the Lammasingi dam, snaking through tiny settlements and sloping fields of corn and pineapples. Peddabarada, a slushy hamlet perched at a slight incline amid toddy palms, with undulating hills for a backdrop, is home to a branch of Gantam Dora’s family that claims to possess the last of his weapons—a country sword and a knife covered in rust, fished out from an aluminium chest stuffed with clothes and household sundries. Babu Rao, 50, Neelakanta Rao, 40, and Ram Babu, 35, are grandsons of Dora’s daughter Sanyasamma. They grew up whispering imagined recipes to a secret family potion that made Gantayya’s bones invincible, their hearts warmed by the sense of justice that made him a hero. There is a curious integrity to these folksy fictions that rush in like floodwater to fill in the cracks of history. The Bagathas, a hunting-gathering-toddy tapping- sheep rearing tribe, are facing a long twilight that began with the arrival of the British in the Agency. For as long as anyone can remember, come summer, they would commence their most important festival, itukula panduga or the festival of the brick, with a ritual hunt. A jackfruit would be shot down, declaring open season. The men and women of the village would then disperse into the forests, returning days later with wild game—deer, rabbit, boar. For six years now, there are no animals to be found in the forests around the village, and it is risky to sneak deeper inside. Deprived of podu rights, the Gam brothers cultivated among them a two-acre parcel of land besides two more acres of coffee. “Our people helped build the roads for the British, but they got paid very little for it. Gantam Dora could not tolerate it,” says Gam Babu Rao, a surprisingly smooth orator. He tells a story, a parable of the plunder of their lands, embellished with great detail. It was a year before the fituri and a party of 12 British police officers was rampaging through a village near Sarabhannapalem, ransacking a mosambi orchard. When Mallu Dora and Gantam Dora got word of the attack, they set out brandishing thorny bushes for weapons and sent 11 officers to their graves, cutting off the ear of the lone survivor. “Even today, we are at the mercy of the government,” Babu Rao says. “It could not even build a house each for the five descendants of Gantam Dora.”

FOR ALL THE passions stoked by the clampdown on the rebellion in the Agency, Alluri Sitarama Raju’s army of a few hundred men did not act out of impulse. They cultivated a network of informants, mastered the art of subterfuge, and attacked only from a position of advantage—take for instance the ambush and murder of two British officers at the treacherous Damanapalle ghat—retreating when local support or supplies dwindled. They had managed to outsmart the Malabar special forces, which were sent back in 1923 after months of dormancy. When the rebels resurfaced, stronger than before, the government decided to send for the Assam Rifles, who rolled into Narsipatnam on January 27th, 1924, under the leadership of Major Goodall. At around the same time, TG Rutherford, appointed as special commissioner in charge of Agency operations, imposed punitive taxes on villages that sympathised with the rebels. Warrants were issued against 55 rebels and 182 people related to them. On May 7th, 1924, Alluri Sitarama Raju met his end in Mampa, caught unawares by an Assam Rifles team that was scanning the forest for rebels. “The version that he surrendered willingly has no historical veracity,” says Pala Krushna Moorthy, retired Deputy Director of Archives, Hyderabad, who has authored a book on the rebellion. “In their zeal to glorify and appropriate Alluri, the Raju community has forgotten several truths, the most important among them that he was a champion of pro-tribal reform—an enlightener for the times.”

Local newspapers had never shied of acknowledging Raju’s rising popularity, but true legitimacy came only with the Congress ratifying his martyr status. Gandhi, in the July 18th, 1929 edition of Young India, paid the ultimate tribute: ‘I was presented with a portrait of a young man as that of a great patriot. I did not know anything about Alluri Srirama Raju. Upon enquiry, I was told many stories of his exploits. I thought them to be interesting and inspiring as an instance of sustained bravery and genius, in my opinion misdirected. I therefore asked for an authentic record. M Annapoornaiah, editor of the Telugu paper called The Congress, has kindly sent it to me. I have considerably abridged it. Though I have no sympathy with and cannot admire armed rebellion, I cannot withhold my homage for a youth so brave, so sacrificing, so simple and so noble in character as young Sri Rama Raju. If the facts collected by Annapoornaiah are true, Raju was (if he is really dead) not a fituri but a great hero.’ Dozens of families in the Agency areas await the day they can build such thought-monuments in memory of their forefathers.

Also Read

Other Articles of Freedom Issue 2018

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

MOst Popular

3

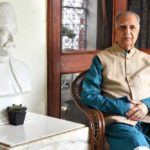

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Crashcause.jpg)

More Columns

Bihar: On the Road to Progress Open Avenues

The Bihar Model: Balancing Governance, Growth and Inclusion Open Avenues

Caution: Contents May Be Delicious V Shoba