Shivnath Jha: The Last Pursuit

The man has made it his mission to trace the bloodline of freedom fighters

Lhendup G Bhutia

Lhendup G Bhutia

Lhendup G Bhutia

Lhendup G Bhutia

|

09 Aug, 2018

|

09 Aug, 2018

/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Thelastpursuit1.jpg)

THERE ARE several disagreements over the story of the Indian revolutionary, Udham Singh. Some accounts place him in Jallianwala Bagh during the massacre of April 13th, 1919. He was apparently serving water to the crowd when the shooting happened. Others claim he was nowhere around the area; he was probably working somewhere in East Africa. Then there is the story of a book he carried to Caxton Hall in London, whose pages had apparently been cut in such a manner that he could conceal the gun with which he killed Michael O’Dwyer, the Lieutenant Governor of Punjab during the massacre. But this too is contested. Apparently, the book was just a pocket diary, far too small to hide a firearm.

But perhaps the most enduring dispute amongst these is the question of who he intended to kill in Caxton Hall. That day— 13th March, 1940, almost 21 years after the massacre at Jallianwala Bagh—‘a burly Sikh’ (according to the book Murders of the Black Museum, which details some of Britain’s most famous crimes of the last century) walked to the front of the hall at the end of a lecture attended by an estimated 160 people, and emptied the contents of his revolver into the platform, killing O’Dwyer, a speaker, almost immediately, while injuring several others. By assassinating O’Dwyer, ‘the burly Sikh’ was avenging the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre. But some have wondered if Singh had not mistaken O’Dwyer to be General Reginald Dyer, the man who ordered the killings. In his diaries, Singh had reportedly misspelt O’Dwyer’s name as ‘O’Dyer’, resulting in this theory. Murders of the Black Museum also claims, ‘It seems that Singh may have confused O’Dwyer with General Dyer.’ That there was a mix-up has been vigorously disputed. Many historians have pointed out that Dyer died many years before the assassination, and Singh would certainly have been aware of it.

Today, so many years after the event, Udham Singh’s descendant Jagga Singh does little to nix the mix-up theory. Speaking of it, he mixes the two names up repeatedly.

“When Shaheed Udham Singhji killed General Dyer, he did not think what will happen to him,” Jagga says. “He was killing General Dyer for the country. My elders used to say…”

Michael O’Dwyer, not General Dyer, he is reminded. “Yes, yes, Michael O’Dwyer,” he says, and resumes. “My elders used to say the whole family was shocked when they heard he killed him. Because [after the massacre], whenever he visited, he did not show how affected he was. He never gave any hint he was going to take revenge.”

But as he recounts the story, Jagga is soon wrapped up in passion, and before long, O’Dwyer becomes General Dyer again.

One cannot fault him much. By his own admission, Jagga and his immediate family have had such a hard life that he never understood the importance of Udham Singh until recently. Descendants of Aas Kaur, Udham Singh’s sister (Udham Singh was never married and did not have any children), once owned farmland, he says, but over the years, the land was gradually sold for sustenance. By the time his father Jeet Singh came of working age, he had no alternative but to work as a construction labourer, earning until recently a daily wage of about Rs 120. His elder brother supplements the family income by painting homes. Jagga, who quit education after completing Class 10, found employment in a small cloth establishment. They lived in a rented tenement of a single room until recently, steeped in debt.

The figure of Udham Singh as a martyr, through films, memorials and events, looms large over Punjab even today. But for the son of a construction labourer just about making ends meet, Udham Singh— even though discussed at home when Jagga was a kid— was little more than a name. “My grandparents and elders used to talk about him a lot, but I didn’t pay much attention. When I was growing up, I never understood much about him. And life was very tough for us,” he says. “Nowadays, I have come to realise what he did. It fills me with respect and pride that my ancestor did such a brave thing.”

If you ask Jagga how he came to such a realisation, he is ready with the year when it all began: 2011.

He was at the shop where he worked then, he says, when he heard someone from Delhi had come to his house looking for him and his family. “I was surprised because nobody ever comes from another place like Delhi to meet us,” Jagga says.

The visitor, Shivnath Jha, hadn’t just dropped in. He had been travelling all around Punjab for months to trace the family. “I was moving around everywhere,” he says. “I first went to find them in Amritsar. Somebody there told me to go to Kurukshetra. Until somebody pointed me towards Sunam.” Jagga remembers being very surprised by his questions. “He was asking us, ‘Are you the descendants of Aas Kaur?’ ‘Are you the grandchildren of Bachan Singh, Aas Kaur’s son?’ He was looking through our ID papers,” he recalls. What Jha was doing was trying to establish if Jagga and his family were indeed related to Udham Singh.

According to Jagga, nobody had ever done that before. Apart from a few people, nobody really knew about their relationship with Udham Singh, and no one had ever expressed any interest in exploring it.

Jha claims to have traced the bloodlines of around 72 freedom fighters. These include revolutionaries of the 20th century’s first half

But to Jha, finding the descendants of Udham Singh wasn’t just his sole objective. Shocked to see their financial state, and to see Jeet Singh, well over 60 years old, working as a labourer at a construction site, he wanted to rehabilitate the family.

In the next few months, Jha managed to raise Rs 11 lakh from an MP (Vijay Darda, who also owns a newspaper). He arranged press conferences and interviews for the family. With the money, Jagga says, they were able to buy the house they lived in and rebuild it. They also paid off all their debt and ensured, Jagga says, that his father Jeet did not have to work anymore.

But their troubles, although attenuated, haven’t all gone away. Jagga wants the stability of a government job. Back in 2006, some elders in his family had managed to meet Amarinder Singh, Chief Minister of Punjab then, and managed to secure a letter recommending Jagga for a government job. A year later, before the promise could materialise, the Amarinder Singh government lost power and Jagga was left in the lurch. Jagga has spent the last several years trying to secure state employment. “Any government job will do,” he says, “even a peon’s.” What has not helped is the presence of a vast array of cousins and relatives, all of them in poor financial condition and using their links with Udham Singh to demand jobs and financial support.

Jagga now routinely threatens to commit suicide or embarks upon fasts-unto- death. He recently returned from a protest in Delhi, and is currently planning to organise another one in his hometown.

Jha, however, has moved on to the next descendant.

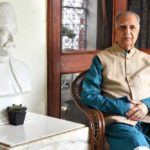

JHA, A FORMER journalist, has an unusual preoccupation. Born and raised in Bihar and now based in Delhi, he looks for the descendants of what he calls ‘forgotten freedom fighters’. He claims to have traced the bloodlines of around 72 freedom fighters. These include revolutionaries of the 20th century’s first half, like Udham Singh, Batukeshwar Dutt (Bhagat Singh’s companion, who unlike his better known friend, lived on to see the country’s Independence), Shivaram Rajguru (hanged along with Bhagat Singh) and Ram Prasad Bismil (hanged for the Kakori case); and also 19th century ones such as Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi, Tantia Tope and Bahadur Shah Zafar involved in the 1857 Uprising. He says he has managed to help about five so far. “The stories of most freedom fighters are gradually being forgotten. There are a handful we still know of, people who made big contributions like Mahatma Gandhi and Nehru,” Jha says. “But the story of our freedom struggle is more complicated, more vast, and there are contributions of many. We can’t just forget them.”

Jha himself had a tough childhood. Growing up in small-town Darbhanga in Bihar, he used to sell newspapers while completing his schooling. He later became a journalist and worked at newspapers in different cities. In 2006, he got involved in what he calls “this location business”. The last job he held was at an Australian radio station’s Hindi language service a few years ago. He now focuses entirely on locating and raising finances for descendants in poor financial shape, he says. He lives with his wife and son. The wife, a school teacher, earns for the family.

Udham Singh looms large over Punjab even today. But for Jagga, the son of a construction worker, it was little more than a name

Jha first got interested in this mission when he was acquainted with the shehnai maestro Ustad Bismillah Khan. He had been working on a book of photographs on Khan’s life and work, and often visited the ageing musician at his Varanasi home. He was deeply moved with the Ustad’s simple manner, living in a rundown house, surrounded by a vast family of innumerable sons, daughters, their spouses, nephews and grandchildren.

Khan, despite his fame, was going through a hard time financially. Jha managed to raise the issue online and in newspapers, eventually managing to get the then Science and Technology Minister Kapil Sibal to loosen his purse strings in 2006. But it was the musician’s other wish—performing at India Gate one last time in memory of those who had died for the country—that Jha most wanted to see fulfilled. Khan was already 91 then. By the time an invitation came from the Home Ministry, the musician had fallen ill. He died soon after. “I felt very bad that Ustad couldn’t do this. That is when I began to think, even if I couldn’t fulfil his wish, maybe I could focus on the martyrs who Ustad wanted to honour. At least I could try and honour their families,” Jha says.

There are an estimated 170,000 people, Jha says, either freedom fighters or their dependants, who each draw a monthly pension close to Rs 30,000. The Home Ministry had told the Central Information Commission in 2009 that so far 170,000 cases had been sanctioned pension from about 700,000 applications. The Ministry, however, did admit that it had no consolidated list of all 170,000 pensioner names. According to Jha, the entire system is a complete mess. He has learnt there are several dependents who don’t receive anything at all, or only get a measly fraction of the sanctioned pension. “Nobody really knows what is happening,” he says, “Who is receiving the pension? Is the recipient even genuine? Or, who is siphoning off the cash?”

The key to locating descendants so many decades and, in some cases, even a century or more after their freedom fighter ancestor has passed away, is simply by looking hard, Jha says. He usually starts by zeroing in on a particular district or village where a particular freedom fighter hailed from or died, or where his family was last heard from, and then he works his way from there, contacting the elderly, local journalists and government officials. “I can go from the panchayat to Parliament. Very often people like postmen are very helpful.” Sometimes the family will have moved, he says, and this will mean a time- consuming process. But usually there is someone in the area the family hailed from who has heard where they have moved and may even have an exact address. Often, especially in cases where the descendants are poor and under-educated, many of them will not have migrated.

Sometimes, the find turns out to be remarkably easy, although no less shocking.

This happened a few years ago when he began to look for descendants of the last Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar. Several years prior to that, as a journalist working in a Kolkata-based newspaper, he would occasionally hear from his colleagues that a direct descendant of the last Mughal emperor called Mirza Mohammad Bedaar Bakht lived in the city and that he was financially in a bad way. Very few newspapers outside Kolkata had then written about Bedaar Bakht or his family.

So in 2007, when Jha returned to Kolkata to look for him, he found himself, in just a matter of days, on the outskirts of the city, seated in a tiny tenement in a slum by the river Hooghly. Bedaar Bakht, the only officially recognised direct descendant of Bahadur Shah Zafar in India, had died many years earlier. But his wife, Sultana Begum, and six children—five daughters and a son—were still around. All the children, except a daughter named Raunaq, had left Sultana Begum behind. And the wife of a direct descendant of the once famed Mughal family was eking out a living by running a tea stall. “It was very shocking for me,” Jha says. “I had heard they were in a bad way. But I never imagined things would have been this bad.” Jha managed to raise around Rs 2 lakh for Begum and secured a job in Coal India for Raunaq.

Today, Begum remembers herself as a 13-year-old in the mid-1960s playing outside her home in Kolkata, being told by her mother that she was to get married that day. “My mother said, ‘He is from Akbar raja’s family.’ I said, ‘Hoga koi Akbar- Shakbar (Must be some Akbar-Shakbar),’” she recalls. Her marriage to Bakht, already 45, had been fixed by an aunt. So she was bathed, dressed and married off that day.

Jha found Vinayak, a descendant of Tantia Tope, in Bithur, running a small grocery store and doubling up as a priest to supplement his income

It was only later, Begum says, as she grew older and fonder of her husband that she understood the importance of his ancestry. “He used to tell me stories of how he was moved from one place to another in secret before he finally reached Kolkata,” she says. “I used to listen in awe.”

After the 1857 War of Independence, Bahadur Shah Zafar was stripped of his property and banished to Rangoon along with a few surviving members of his family. This included Prince Jewan Bakht, according to some accounts, the king’s only surviving son. Jewan Bakht had a son, Jamshed Bakht, who in turn had Bedaar Bakht from his second wife Nadir Jehan. Bedaar moved out of Rangoon as a youngster under the care of a guardian, and travelled to various parts of India, before finally settling in Kolkata. For a long time, he drew only Rs 400 from the Government as pension. This has now been increased to Rs 6,000.

Jha’s intervention has helped, Begum admits. But she claims she needs more aid. She has wound up her tea stall and is now completely dependent on the pension. “I need some [financial] safety. I would like to spend the remainder of my life in a better house,” she says.

According to Jha, most of the descendants he has found so far are invariably in a state similar to Begum. Families who have educated themselves are living fairly stable middle-class lives (he mentions Bharati Bagchi, the daughter of Batukeshwar Dutt, who recently retired as a professor of economics in Patna). But a vast majority are people who have been left behind by the country’s progress.

One of his favourite success stories is that of Vinayak Rao Tope. A descendant of Tantia Tope, the fierce and celebrated revolutionary from the 1857 war who had led several raids against British forces, even seizing Gwalior once while fighting alongside Rani Lakshmibai, Jha found Vinayak in Bithur, a town close to Kanpur, running a small grocery store and doubling up as a priest to supplement his income.

Vinayak is the grandson of Lakshman Rao Tope, one of Tantia Tope’s six brothers. Tantia had no child of his own and apart from the brothers, also had two sisters. After Tantia was captured, the rest of his family was also arrested. They were released later and returned to their home in Bithur, Vinayak recalls, but the family then soon split, some moving to Nepal, some to other parts of India.

As a child, Vinayak says, he listened with fascination as his father and other relatives discussed Tantia and his exploits. They would frequently talk about how all of Tantia’s family was arrested, and how, until the country’s Independence, the family kept a low profile, never revealing their identity in fear of being arrested again. One of the myths surrounding Tantia is that the revolutionary was never hanged in 1859 at Shivpuri. Someone else was hanged in his place, as this story goes, and Tantia lived on in hiding for the rest of his life. Vinayak says he’s heard this story too. But his family has always believed Tantia died then.

Jha thought he would have a tough time locating the Tope family, given the news that all his brothers had split up. But when he began to make the rounds in Kanpur, he found that one of Tantia’s brothers, Lakshman Rao, and his descendants had never left Bithur. They, in fact, lived in the same house. And when Jha visited Vinayak, every few minutes he would disappear somewhere inside the house and emerge with a sword or some other ancient weapon that Tantia had once used.

According to Vinayak, very few outside the town knew about their ancestry. Jha managed to secure a meeting of the Topes with Lalu Prasad Yadav, the then Railways Minister, who got Vinayak’s two daughters, Pragati and Tripti, jobs as commercial assistants at the Kanpur terminal of Container Corporation of India, a subsidiary of the Railways. Monetary help of over Rs 5 lakh was also arranged.

Since then, Vinayak has shut down his grocery store. He still moonlights as a priest because the job gives him satisfaction. Both his daughters are married. And he would like his 26-year-old son to get a job, he says. But he is not too worried.

There is a lot more fame and respect accorded to his family in the neighbourhood now. And four years earlier, betting that this new-found respect could translate into electoral votes, a political party (Swarajya Party of India) convinced him to stand in the General Election. “They told me they would help me win the election. And maybe in the future, with enough votes, I would become their CM candidate,” he says. Vinayak suffered a massive defeat. The winner, BJP’s Murli Manohar Joshi, got close to 475,000 votes. Vinayak got 780.

“The party didn’t support me much. And so I lost,” he says. “But back then, when they said I could become a CM candidate, I was very happy. Just to think that Tantia Tope’s descendant could become a CM made me very happy.”

Also Read

Other Articles of Freedom Issue 2018

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover-Shubman-Gill-1.jpg)

More Columns

Shubhanshu Shukla Return Date Set For July 14 Open

Rhythm Streets Aditya Mani Jha

Mumbai’s Glazed Memories Shaikh Ayaz