Truth and Faith

The Places of Worship Act stands in the way of reclamation of religious sites of one community allegedly occupied by another. Its constitutional validity was waiting to be challenged

J Sai Deepak

J Sai Deepak

J Sai Deepak

J Sai Deepak

|

19 Mar, 2021

|

19 Mar, 2021

/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Truthandfaith1.jpg)

(Illustration: Saurabh Singh)

ON FRIDAY, MARCH 12th, after a Petition filed before the Supreme Court challenging the constitutional validity of the Places of Worship Act 1991, aptly acronymised as the PoW Act, the Apex Court issued notice to the Centre directing it to respond to the Petition. A brief overview of the backdrop to the PoW Act and its framework is necessary in order to understand the nature of the challenge to it in the Petition. The legislation was enacted by the Narasimha Rao-led Congress Government and its central provisions came into force on September 18th, 1991. The Act is designed, as its Preamble states, to ‘prohibit conversion of any place of worship and to provide for the maintenance of the religious character of any place of worship as it existed on the 15th day of August, 1947…’ This object is further codified in Sections 3 and 4 of the Act subject to certain exceptions identified in Section 4. Broadly speaking, this legislation stands in the way of reclamation of religious sites of any community which, it believes, are occupied by another.

While the statute does appear to be neutrally worded on the face of it, the backdrop of its passing and the exception it carves out make it clear that it forcibly forecloses the fundamental rights of Indic communities at the altar of ‘secularism’. The statute was enacted by the Congress Government in the backdrop of the Shri Ram Janmabhoomi Movement which had a clear bearing on the scheme of the Act. This is because the only exception to the application of the statute is expressly identified in Section 5, namely the hitherto pending legal dispute surrounding the ownership of the Shri Ram Janmabhoomi in Ayodhya. In other words, other than the then-pending legal proceedings in relation to the birthplace of Shri Ram at Ayodhya, all other similar proceedings, either pending or prospective, are barred by the Act. Naturally, this raises the following questions in relation to the Act and its passing by the dispensation in 1991:

– How does creating an exception in favour of the Shri Ram Janmabhoomi alone pass muster on the anvils of Articles 14, 25, 26 and 29 at the very least? Can it be constitutionally sustained that the rights of the parties involved in the Ayodhya dispute were more equal than the rights of similarly situated parties in relation to other sites?

– What was the factual basis for barring or terminating legal proceedings for reclamation of other holy sites over which two or more parties have competing claims of ownership? Given that consultation with affected parties appears to be the flavour of the season in the context of the farm laws, what kind of consultations were undertaken by the Government in 1991 with members of Indic communities and claimants of Temple property before the PoW Act was passed?

– As a corollary to the above question, did the dispensation of the day at least undertake a baseline study of the number of contested sites across the country to understand the broad nature of the claims involved? After all, to presume that such claims for reclamation were/are limited only to Ayodhya, Kashi and Mathura, is to turn a blind eye to thousands of similarly credible, reasonable and justiciable claims which are spread across the country.

None of the above questions was answered with any degree of specificity during the course of the cursory parliamentary debates held on the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Bill. The Bill, which was introduced in Lok Sabha on August 23rd, 1991, was passed on September 10th, 1991 with the debates being held only on August 23rd, 1991, September 9th, 1991 and September 10th, 1991. In fact, the surreptitious manner in which the Bill was introduced in Lok Sabha without following rules of notice and the haste with which it was passed were criticised by Ram Naik of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) who called it “the blackest Bill in the Indian Parliament”.

In addition to the above issues which demand clear and cogent answers over and above party politics, the following presumptions/myths too need to be busted:

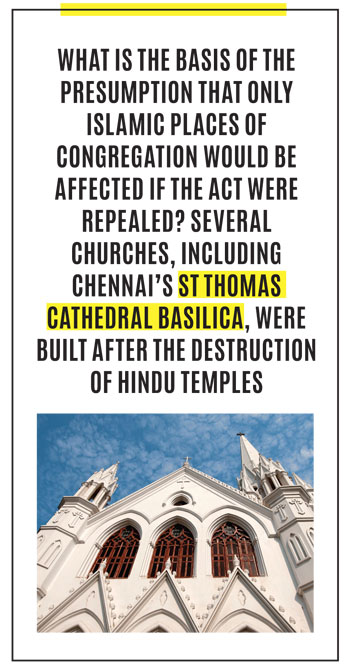

– What is the basis of the presumption that only Islamic places of prayer/congregation would be the most affected if the Act were to be struck down or repealed? After all, there is enough historical evidence of several Churches having been built after the destruction of Hindu Temples. For instance, history suggests that the well-known St Thomas Cathedral Basilica in Chennai was built by the Portuguese after destroying the original Shri Kapaleeshwarar Temple which had to be moved to Mylapore to protect the Deities from the marauding Portuguese Christians. Similarly, AK Priolkar’s book on the Portuguese Inquisition in Goa, also known as the Goan Inquisition, and several other scholarly works credibly support the claim that several Churches in Goa and across the Konkan were built after razing Hindu places of worship to the ground.

– Importantly, since the PoW Act is neutrally worded, in the sense that it does not ostensibly target or foreclose the rights of any particular community, why don’t we apprehend claims by non-Hindus, in particular Muslims and Christians, on Hindu places of worship if the Act were to be struck down or repealed? Doesn’t this mean that the opponents of Hindu reclamation of sites are aware of historical realities?

– If Jains and Buddhists too have claims over Hindu Temples or Mosques or Churches, why should the Act come in the way of their right to prove their claims with evidence along the same lines as the Ayodhya case? At least this will settle the question of destruction of Jain and Buddhist places of worship by ‘Brahminical Hindus’ which is constantly raised each time a claim is made by Hindus on occupied religious sites.

The catch-all response to all the questions raised above is typically and predictably ‘Secularism’, which is offered as a justification for the PoW Act to keep ‘communal politics’ at bay. This is perhaps the most superficial, insensitive and ahistorical response to issues raised by the challenge to the PoW Act since the reality of Indian politics has been communal politics ever since the Two-Nation Theory led to the Partition of Bharat. Of course, the Supreme Court’s inadequate, legally untenable and inconsequential attempt to lend its seal of approval to the PoW Act in its Ayodhya Verdict of November 9th, 2019 can be expected to be marshalled in support of the secularism defence. The judgment may even be cited by the proponents of the PoW Act to question the very maintainability of the Petition challenging the Act. Unfortunately for them, the Ayodhya judgment does not remotely come in the way of the challenge to the PoW Act for reasons explained below.

In the said verdict, curiously the Supreme Court deemed it fit to discuss the provisions of the PoW Act despite the non-application of the Act to the Shri Ram Janmabhoomi dispute. In fact, the Court took express note of the non-application of the Act to the Ayodhya dispute in Paragraph 80 of its judgment. This means the Court was clearly aware of the legal consequence of the exception under Section 5, which was to leave the then pending legal proceedings with respect to the site in Ayodhya untouched and uninfluenced by the express provisions of the PoW Act or its purported ‘secular’ import. Therefore, there was no need, legal or otherwise, for the Supreme Court to discuss the Act in the context of the Shri Ram Janmabhoomi case which was meant to be adjudicated on the basis of established legal principles that applied to property disputes. And yet, the Court discussed the Act in over 10 pages with the central thrust being the Constitution’s commitment to ‘secularism’.

Perhaps, the intention behind the Court’s legally unnecessary discussion on the Act was to dissuade any future constitutional challenge to the PoW Act so as to prevent Ayodhya-like claims from being revived or initiated. However, as demonstrated by this author in an article published in The New Indian Express on June 3rd, 2020, the Court’s discussion of the statute and secularism were both superfluous and irrelevant to the Ayodhya dispute, apart from the trigger for the said discussion in the judgment being factually misplaced and incorrect. Therefore, legally speaking, the Court’s observations in relation to the Act in the Ayodhya judgment have no precedential value and do not have the force of law under Article 141 of the Constitution.

This position is supported by the law laid down by the Court itself in several judgments. Illustratively, in Jagdish Lal vs State of Haryana (1997) and Director of Settlements, A.P. & Ors vs M.R. Apparao & Anr (2002), the Court had categorically held that only those of its adjudicatory observations in a given judgment, which related to issues that arose for its consideration in a given case, would have a legally binding character under Article 141. The logic underlying the said position is that a Court of law, not being an academic forum, is not expected to answer questions which do not arise before it for its adjudication. Applying the said principle to the Court’s discussion on the PoW Act in the Ayodhya verdict, since such discussion was neither relevant for adjudication of the title dispute in the facts of that case nor would its absence have made a difference to the outcome in any manner, the discussion does not have a legally binding character under Article 141.

Apart from the legal and constitutional perspectives, the other perspective that warrants application in the context of the challenge to the PoW Act is the decolonial perspective. It is easy to succumb to the temptation of viewing the entire issue through the jaded lens of ‘communal politics’, especially by those who continue to have a problem with the reconstruction of the Shri Ram Temple in Ayodhya despite the Supreme Court upholding the claim of the Temple side. Unfortunately, the meta issue has either never been adequately understood or clearly articulated from the perspective of indigeneity and through the framework of decoloniality in most circles which have an opinion on such issues and their history. Seldom has one come across a nuanced perspective from the opponents of Temple reclamation which strikes a balance between indigenous civilisational rights on the one hand and the legitimate interest in preserving communal harmony on the other. Instead, invariably the approach has been to either question the very legitimacy of the claims of indigenous claimants, or to adopt a patronising approach towards them which categorically expects them to sacrifice their beliefs and rights at the altar of an uneasy ‘peace’ even if their claims are supported by history. In both instances, it is a case of ‘talking down’ to the native, which is textbook coloniality at work.

The stark irony in the attitude of the colonialised opponents of Temple Reclamation is the convenience in their application of moral standards and use of history. While colonial interpretations of indigenous sources of history are typically treated as reliable to address issues relating to caste to further the goal of social justice which is again defined unilaterally by a select few, sources of history which attest to the existence of indigenous religious sites and their occupation are rejected as unreliable, apocryphal and even fabricated. The expedient reliance on or rejection of indigenous epistemology and voices depending on what fits the worldview and narrative of the colonialised elites has been the story of the better part of independent India, which negates the idea of Bharat. Unfortunately, such an attitude is not limited to thought or expression of thought but has also translated to legislative action and judicial treatment of indigenous rights and expectations.

The PoW Act is one such example of a manifestly unjust legislation passed by a colonialised Indian State against the fundamental rights of adherents of indigenous faith systems. Simply put, the embargo under the PoW Act on one’s exercise of rights to reclaim one’s place of worship is directly at loggerheads with rights guaranteed under Articles 25 and 26. Even if a lone individual asserts the right of reclamation and the rest of the community has either forgiven, or worse, forgotten, no canon of secularism or principle of fairness or justice in any civilised jurisdiction can mandate that an individual or a community must sacrifice her or its right to legally reclaim the nerve centres of civilisational identity. After all, this has been the position of the Supreme Court in relation to individual rights and their importance in the constellation of fundamental rights in matters relating to entry into places of worship.

At the very least, members of the community must have the right to prove their case in a Court of law. To deprive that legal remedy through legislation passed without any consultation with members of affected indigenous communities is to add insult to injury. Decoloniality demands that no one other than a victim has the right to forgive on behalf of the victim, or presume that the victim has either forgiven or forgotten. To do otherwise is to be insensitive to historical injustice. Since neither Parliament nor the Apex Court has considered these aspects, the PoW Act remains as vulnerable to a constitutional challenge as it was before the Ayodhya verdict, and is waiting to be struck down or, better, repealed by the Legislature.

Finally, in the backdrop of the ongoing movement against European coloniality in various parts of the world, it must not be forgotten that both the Indian Constitution and decoloniality put a premium on social justice and there can be no social justice at the expense of the truth, nor is lasting peace possible until the truth is demonstrably established, acknowledged and accounted for.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover-Shubman-Gill-1.jpg)

More Columns

‘Fuel to Air India plane was cut off before crash’ Open

Shubhanshu Shukla Return Date Set For July 14 Open

Rhythm Streets Aditya Mani Jha