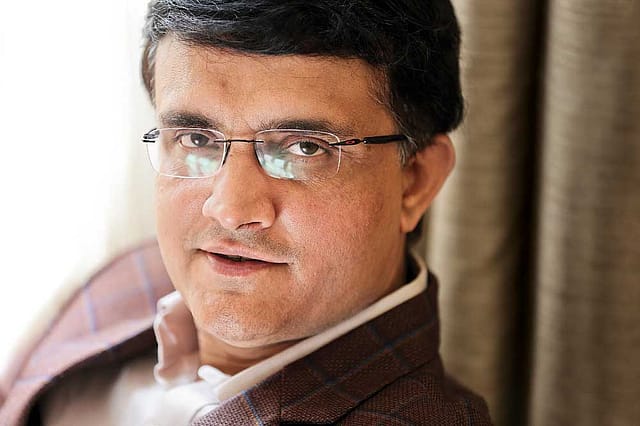

Sourav Ganguly: ‘Under me, players weren’t picked and dropped at my whim and fancy’

OF ALL CAPTAINS to have led the Indian cricket team, Sourav Ganguly's tenure at the helm perhaps mattered the most. MS Dhoni has a better Test record than Ganguly in terms of overall wins, and Virat Kohli, the current skipper, is aggressive in ways that Ganguly could never be—both on and off the field. Numbers and aggression, captain Ganguly's most defining attributes, bettered and improved by his successors. But here's what we tend to forget. Without Ganguly, chances are that we wouldn't know, recognise and celebrate Indian cricket the way we do today.

When Ganguly was handed the wheel, the game in India hadn't just screeched towards the proverbial crossroads; rather, it had crashed bonnet- first into a dead-end. Cricket's biggest match-fixing scandal had just broken and the Indian dressing room was at the centre of its cancerous outburst, consuming, among others, India's predominant captain through the 90s and its then-incumbent coach, who also happened to be a national hero. How deep the rot had gone, one will never know. But Ganguly, like a wide-ranging blast of therapy, did not care for specifics.

Consider also this poignant statistic: In the 1990s, India had won all of one Test match away from home. Yes, one away win in a decade. After Ganguly took over in 2000, the team won 11 Tests overseas in six years—including a Test series victory in Pakistan and a tied tour of Australia. Gone were the days of individual talent in leaderless set-ups. With Ganguly's assistance, the Indian team had grown a spine. And a pair of balls too.

Ahead of the launch of his memoir, A Century Is Not Enough (Juggernaut; 280 pages; Rs 699), Ganguly speaks to Open on his greatest contribution to Indian cricket, the art of leadership.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

The current Indian captain is known for his aggression and being authoritative as a leader—traits first brought into the Indian dressing room when you took over. What are your thoughts on his captaincy style?

I'm a Virat Kohli fan. But I will ask him the next time I meet him, 'Every time a wicket falls, who do you show your fist to?' I honestly don't know. Maybe towards you guys in the press (laughs). But I will surely make a note to ask him because even I want to know.

Whatever Virat does, both as player and captain, I think he has got the good of Indian cricket at heart. And in my opinion, Indian cricket needs him as captain at the moment. The players are young and Virat shoulders the team. Just look at this recent ODI series in South Africa. The others chipped in—a fifty here, a fifty there. But we won because of Virat's three hundreds. That kind of consistency is ridiculous. I love Virat Kohli. He has taken Indian cricket to new heights.

But Kohli's greatness as a batsman is often mistaken for his greatness as a leader. Purely as a captain, how would you judge him?

We often tend to judge present-day captains against captains from different eras. That isn't the right way to do it. We shouldn't and cannot compare across eras. Situations are different, the game is different, as are the bowling attacks and the mindset of the players. The best teams have a flow in their leadership, a flow that is similar to running a relay race. When it is your time with the baton, you have to do the best you can. And once your time is finished, you pass on the baton and hope that the next person is faster and stronger.

You received this baton in extraordinary circumstances. In A Century Is Not Enough, you mention that in the year 2000 you were elated to know that your turn had finally arrived. Did you underestimate just how difficult it was going to be, given the cloud of corruption that hung over a broken dressing room?

When I was appointed captain, the selectors and the Board had taken a few brave decisions already. This is when some new players came in and I had no option but to go and play with them. Sometimes I feel in life when you don't have any option and you have to succeed irrespective of anything and everything, it works. So, I decided, yes, that's what I have and such are the times, and I am going to do the best that I can.

I had exceptional players, you know—Sachin (Tendulkar), Rahul (Dravid), Anil (Kumble), VVS (Laxman). [We were] a young team trying to be very, very good and it was actually worthwhile going through that experience together. It made us stronger. The time we had over the next 5-6 years was absolutely amazing.

Did the art of captaincy come naturally to you? What was it like to take over a side with great individual talent that hadn't yet learned to play as a team?

I did not have any template, so I did what I thought was right. I honestly didn't know if what I was doing was right or wrong. All I needed to know was how to win cricket matches. And all I had to do was get us, as a team, across the line with my leadership and that's all I focused on. I did what my instincts let me do.

I also think I was a very good man manager; that helped individuals come together as a unit. It was a very important aspect of my captaincy, of my leadership. I'm not the sort of person who sits on someone's head; I let them be who they are. I wasn't the kind of captain who was constantly pushing my thoughts down everybody's throat. I allowed my players to blossom. With God's grace, I had the ability to identify players who could do well for the country. When I picked them, I allowed them freedom to play and to express themselves in the dressing room. I think that worked. That's what I wanted to instil in a young team—'Be independent, be free, but I need each one of you to win me cricket matches.'

What did it take to be a leader when your peers were such heavyweights? It couldn't have been easy to ask someone like Anil Kumble to sit out of a playing eleven.

Very tough. Very, very hard (laughs). To tell a player of Anil Kumble's calibre, 'You won't be playing this game'—impossible! The look I used to get from him was ferocious. But I liked it. I always loved players who would ask me why I did not pick them when such an occasion arose. I did not want players who would say, 'Thank God, I've got a day off.' I wanted my dressing room to be filled with the first kind.

By asking Anil to miss the odd game here and there, he didn't think I had lost all faith in his abilities. That's very important, to instil that faith and that level of trust in all your players. It helps when you have to leave them out and it helps when you bring them back in because clarity and transparency are of utmost importance when you work in a team environment.

You have been credited with blooding youngsters such as Virender Sehwag, Yuvraj Singh and Zaheer Khan, to name a few. But you also backed them when they failed. Did this knack of fighting for players come from your own insecurities as a young batsman in constant fear of the axe in the 90s?

Yes, most certainly. But I didn't tell the young guys that even if they don't perform, they will continue to play. They knew my demands. I told them that everyone fails from time to time but when you do score runs or pick wickets, make sure the runs and wickets are good enough to win matches for us. The message was pretty clear that they would get a fair trial. Under me, they wouldn't be picked and dropped at whim and fancy, and careers wouldn't come to a standstill. I wanted to take the fear factor away.

The fear of failure is so dominant in our profession because once you get dropped, the chances of people forgetting about you are very high. So, it was important that communication, from my end, was always clear: 'This is what I demand of you and this is what you need to do.'

Not too many realise that the remarkable series against Australia in 2001 was your first as a leader in Test cricket against a side that wasn't Bangladesh or Zimbabwe. What was it like to take on the best Test team of that era in your very first challenge as captain?

Phenomenal. I never saw the West Indies team of the 70s, but I saw, and played against, the Australia of the late 90s and the 2000s. There was no weak link in that team. I think it was Harbhajan (Singh) who put it best when he once told me, "Sabko out kar dete hain phir Gilchrist aa jaata hai saat number pe (we dismiss the entire batting order then Gilchrist walks in to bat at No 7)."

Which is precisely what happened in the first Test of that series in Mumbai. You had Australia cornered at 99 for 5 in the first innings. Then Adam Gilchrist walked in and took the game away.

We got smashed not just by Gilchrist and Australia, but by the media and the selectors as well. That's the fun bit of captaining. You get challenged at every level and the fact that you are representing your country demands that you bounce back. If you are down, then find a way back up because sport is all real life, nothing is scripted or camouflaged and there is no place to hide. That's the challenge we lived with all our lives and it made us transparent people.

Give us an idea of your mental state following that loss. Australia had just won their 16th Test match in a row and your Australian counterpart, Steve Waugh, was on the verge of winning a series in India, which he famously called the 'final frontier' before the series began.

I flew back to Kolkata the very night we lost in Mumbai, two days before the Test's scheduled end. The next morning, I went straight to the ground [Eden Gardens] to assess the conditions and to decide who we would play in the eleven in the second test. My early preparation didn't matter as we got battered, again, in the first innings. Australia scored 445 runs. In reply, we got 171 all out. I thought 'gone'. Test match gone. Test series gone. And captaincy gone as well.

I remember at the end of Day Three, after Australia had enforced the follow on, my mother-in-law came to the team hotel. She had brought some home food and we were having a chat in the room about everything but cricket, and she suddenly said, "Sourav, you will win this game." That's the thing with mothers-in- law—they always say the wrong thing at the wrong time (laughs). Back then, I didn't see the funny side of it, so immediately after she left, I called my wife and said, "Why does your mother do this all the time?" She calmed me down and asked me to forget the whole incident. Two days later, we had pulled off one of the greatest comebacks in a Test match ever, and of course, my mother-in-law never lets me forget her words.

After the game, I had invited the team home for dinner.I live in Behala [in Kolkata] and my in-laws' house is next door—house 16 and house 17, right next to each other. As we entered, she was standing in the balcony with a big smile on her face, telling every player as they passed, "I told Sourav this would happen two days ago." I honestly don't know what she was thinking on Day Three, because none of us, apart from VVS and Rahul, was thinking that.

What was the idea behind shuffling the batting order for the second innings? Were both Laxman and Dravid on board with the switch?

It was a tough call to make, but as captain I had to make it. I remember when Laxman got 59 in the first innings, John [Wright, the Indian coach] came up to me and said, "Sourav, let Laxman bat at three." I was thinking along the same line: 'Laxman's just been batting in the middle. Rahul has been out of touch. And we need to do something different. So let's promote VVS.' We did that and it worked. Rahul was pretty upset about it. Then he too scored 180 runs, to go with Laxman's 281, and everything fell into place.

Was demoting Dravid to No 6 as difficult as leaving Kumble out of a side?

Rahul too realised that he wasn't playing well and that we needed to do something about it. When he got that hundred, you could see the anger and the frustration and what it meant to him. You saw him showing his bat [towards the press box]. And I loved it. I think he even became a better player after that innings. He went on to get 80-plus in Chennai and we won the series. That series changed me as well, both as a person and a captain. I would say it was the point when Indian cricket changed, this time for the better.

There was another call you had to make in the Kolkata Test of 2001 that could have gone either way. You prolonged the declaration on Day Five, which began with the anticipation of a Laxman triple-hundred. But well after he was out, India batted on. Did the thought ever cross your mind that the bowlers wouldn't have enough time to pick up 10 wickets?

Even my father was getting upset with me, to tell you the truth. He was watching the game from the office of the Cricket Association of Bengal, where he was vice-president. An hour before lunch on Day Five, I get a note from the dressing room attendant. It's from my father. 'What are you doing? Why aren't you declaring? Don't you want to win this Test match?' the note read. I tore it up and threw it away. He was certain that I had thrown away a golden opportunity to win.

But the only reason I prolonged the declaration was I believed we needed a lead of 370-380 runs against that batting line-up, considering we were going to bowl 70 overs on the final day against them. I did not want to get to a stage where the match could've slipped away; in India things change very quickly on the fourth and fifth days. I did not want the chase to get to a situation where I take the catching fielders away and put them in defensive positions.

You have often said that the 2001 Test series was the high point of your captaincy career. What was your lowest point as a leader?

Not winning the World Cup in 2003. We lost to a fantastic Australian side in the final. That still hurts.

Do you now believe that winning the toss and opting to bowl first in that final in Johannesburg was a blunder?

No. I still think I made the right decision at the toss. We just didn't play well enough—bowled too short on a pitch which offered a lot if the ball was pitched up.

Staying with ODI cricket, you were also one of the world's best batsmen in the format. Were you aware that the game against Pakistan in Gwalior, 2007, would be the last time you would represent India in blue?

I had no idea that it was. Not for a long time after that match and series had ended, to be honest. I had had a big year. I got more than 1,200 ODI runs [1,240 to be precise] in 2007. In fact, across both formats [1,106 Test runs as well, at an average of 61.44]. After that ODI series against Pakistan, we played a Test series against them and I scored a hundred in Eden Gardens in the first game. In the next match, in Bangalore, I scored a double hundred in the first innings and 91 in the second. I was in the form of my life.

Immediately after the Pakistan series, I went to Australia for the Test matches and the terrific form continued there. But all of a sudden, I was told that I would miss the upcoming ODI tri-series [CB Series in 2008] as I was not part of their 2011 World Cup plan. They thought I was too old—I would've been 39 in 2011—for the short-format, and both Rahul and I were pushed aside.

Weird, then, that a career encompassing 11,363 ODI runs was bracketed by neither a great welcome (in Brisbane, 1992), nor a suitable goodbye (in Gwalior, 2007).

Yes, that's the way it goes. I wasn't expecting to debut in Brisbane in 1992 and I surely wasn't expecting to be dropped for four years after just one game. So, those eleven thousand-odd runs were scored in the space of 10 years. That's life. I'm just glad that I finished my Test career on a high—beating the odds to return after my former coach [Greg Chappell] had left me out in 2006; to get all those runs in difficult situations in 2007 and to finish in 2008 against Australia with a series win, a series in which I did fairly well and even struck a hundred.

Post-retirement, from just beyond the boundary rope at Wankhede, you watched Dhoni hit the winning six to win the 2011 World Cup. These were the very men you had fought for when they were establishing themselves. This was the team you had helped assemble. Did it, then, feel like you had won that trophy as well?

I still remember I came down to the ground and stood by the boundary rope to see how it felt to win a World Cup. I was commentating at Wankhede Stadium when the producer told me that I needed to be on air when India wins the World Cup. And I said, "Sorry, no chance." I was not going to do it. I told the producer, "I've listened to everything you have said so far, but I am not going to listen to you now." I really wanted to know what it feels to be on the ground when our boys have a World Cup trophy in their hand. And what an atmosphere it was down there! I get goosebumps thinking about it right now.

Yes, even though I had finished playing for the country, I felt that I was a part of it. These were my boys too. That evening, every Indian felt like they had won the World Cup. I was no exception.