Modi’s Call

LEADERSHIP NEEDS A backdrop to make it, sometime in the future, a story worth retelling. That is why, when the stories of tyrants and redeemers are retold, history becomes a cautionary tale. Everything, in varying degrees of cruelty, began as a project in freedom, whether it was war or revolution. Those who won the wars, not necessarily all of them, weren't model managers of freedom. And those who led the revolutions, mostly all of them, turned the original slogan of freedom into a prescription for terror. Still, we return to their stories to tell the present in more clarifying words. Stories alone remain, as reminders of boundaries set—and defied—by dreamers and warriors.

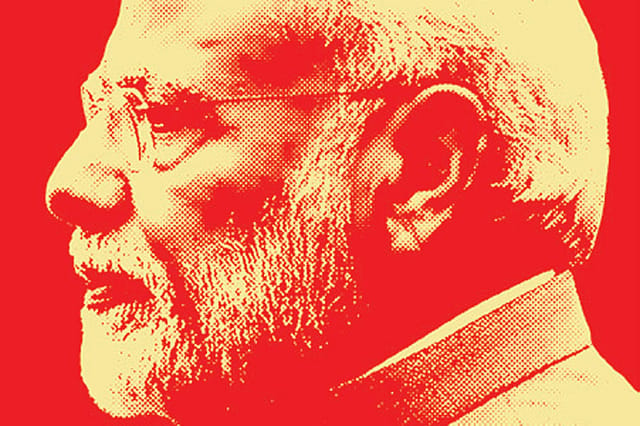

The 21st century, still young, carries the burden of the last. Its larger dramas borrow from the script of the last. Its arbiters—whether wayward liberals or national populists or autocrats who have bestowed on themselves an eternal mandate—occasionally return to the rule books of the last. They have been denied the kind of backdrops that made some past portraits of leadership compelling even now. There are transformative stories still. The morning of September 11th in 2001 changed an American president from a privileged stereotype into an original action hero. In 2008, long before race was a frenzied dispute in the street and in the public square, an African American, a freshman Senator, became the reconciler president on the strength of his stump poetry of change. And in 2014, the Congress century came to an end in India when an outsider, a nationalist who told the Indian story in a vocabulary unfamiliar to the Establishment, stormed Delhi.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

A pandemic, as has been argued in this space before ('Camus, Covid-19 and Leadership', March 30th), is not the kind of backdrop that leaders prefer. It is still testing them, and the days of some in office are counted against the number of infected and dying. It has been a winning battle only for a few; for the most, it's a day-by-day trial by an untameable virus. When it began, there were deniers and cynics, and some saw in it yet another opportunity to tighten their vicious grip on people. And some, to compensate for the economic cost of lockdowns, turned to the politics of fear. Even as the virus spread, in some places, the battle against it was not as fierce as the ideological battles. A virus-driven referendum on leadership has become inevitable.

For Prime Minister Narendra Modi, while he has been battling on one front, another opened along our border with China in the Galwan Valley. In the first battle, against the coronavirus, he was one of the first leaders who understood the enormity of the crisis. The lockdowns saved us from the initial spurt, and it was a lesson in useful fear. India listened to him, followed the instructions, and in enforced isolation, realised the vulnerability of being human. The story would have been worse had Modi behaved like Donald Trump or Boris Johnson. As India climbed up the worst-hit list subsequently, what was revealed in frightening starkness was not a political leadership in denial but one of our shameful inheritances: a healthcare system incapable of coping with the size and inequalities of India. The much-cited Kerala example in effectively containing the pandemic has to be credited to the state's heightened sense of healthcare.

The other challenge that tested Modi's leadership came from the world's most tolerated rogue republic ('Dream and Dictatorship', July 6th). India still suffers from a China complex, a reflection of national diffidence and insufficient faith in the possibilities of democracy. The look-at-China wonderment is perpetuated by a section of our academic and political class dazzled by a gilded autocracy. The country that wanted to be the sole author of the so-called Asian Century was in a permanent mode of disruption-and-diffusion in its relationship with India, the alternative power with the credentials of democracy. The latest display of thuggery was in sync with Beijing's active disrespect for borders and democracy. Modi had to deal with the neighbour's belligerence—and to ignore the liberals who taunted him for his non-dramatic response. All the peaceniks had suddenly turned into convenient warmongers.

Modi knew, as anyone familiar with the psychology of habitual bullies did, his tormentor was not inviting him to a war. Modi's restraint was not a way of giving in to the bully; it was a refusal to bracket India culturally with China. It was an assertion of democracy and morally superior international behaviour. It required a different kind of resoluteness to win an argument—and not to lose territory. In the end, his behaviour was endorsed, and supported, by other democracies.

If it's backdrop that makes the story of leadership, the pandemic and the People's Republic have given us one with no duller passages.