Meeting Our Doppelgängers with Hervé Le Tellier

I remember the joyful shock of reading the French novelist Georges Perec’s A Void, La Disparition in French (1969), translated into English by Gilbert Adair in 1995. Perec was a manic experimenter, stretching the boundaries of storytelling to make the story a meta-mystery. A Void was written without using the letter ‘E’. No ‘he’ or ‘she’, no ‘love’ or ‘hate’, no ‘life’ or ‘death’, no ‘father’ or ‘mother’, and no ‘the’ in this novel, and that Adair could transport that novelty into English was pure magic. Perec’s masterpiece, Life A User’s Manual, came out in French in 1978, translated into English by David Bellos in 1987, and the book, mirroring the splintered quotidian of Parisian life, continues to be a testament to what fiction could do with form to create the puzzle of life. In Perec’s own words, “despite appearances, puzzling is not a solitary game: every move the puzzle makes, the puzzle-maker has made before; every piece the puzzle picks up, and picks up again, and studies and strokes, every combination he tries, and tries at a second time, every blunder and every insight, each hope and each discouragement have all been designed, calculated, and decided by the other.” The narrative puzzle-makers in fiction formed a group called Oulipo, and among its original members were Perec and Italo Calvino. Life A User’s Manual, a burst of imagination in multitudes, is the group’s tallest tower, built on the veiled fantasies of everyday Paris, beginning with these lines culled from a building block: “Yes, it could begin this way, right here, just like that, in a rather slow and ponderous way, in this neutral place that belongs to all and to none, where people pass by almost without seeing each other, where the life of the building regularly and distantly rebounds.” A Void was novel as lipogram, the persistence of absence its only existential presence. The structural wizards of fiction took the art of the novel, perfected as a philosopher’s meditation by the existentialists, to the special zones of subversion.

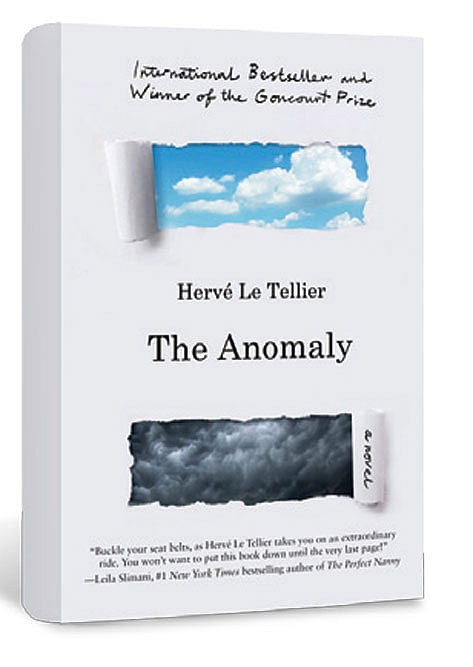

Hervé Le Tellier is a worthy successor to Perec. An upholder of the Oulipo tradition, he has achieved the kind of structural originality—playful and polyphonic— his gurus had played out in their works. His novel, The Anomaly, the 2020 winner of the Goncourt Prize, has already become a publishing sensation at home, translated into English by Adriana Hunter (Other Press, 400 pages, $16.99). A form-shifting, ideas-rich, and mischievous idyll-breaker of a novel, The Anomaly opens with an introduction of some passengers in Air France 006 flight, a Boeing 787, from Paris to New York, in 2021. Blake is an assassin with a perfect cover, for whom “killing isn’t a vacation, it’s a learning.” Victor Miesel, with the looks of “a healthy Kafka who made it past forty,” is an underselling novelist whose titles include The Mountains Will Come to Find Us and Failures That Missed the Mark. He will achieve posthumous fame and sale with The anomaly, and for whom suicide is not about “putting an end to my existence but giving life to immortality.” Lucie Bogaert is a sought-after film editor, and her lover, André, who lives in a vast Haussmann apartment, is an architect whose one current project is in Mumbai. David, a pilot, has been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, with a 20 per cent chance of surviving five years. Sophia is a girl sexually abused by her father, and her closest companion is a frog called Betty. Joanna Wasserman is a lawyer who possesses, in the words of her admirer, a Gothic cathedral as brain, and her lover is a newspaper cartoonist. Slimboy, with his camouflaged sexuality, is a Nigerian popstar who has sung alongside Beyoncé, dueted with Eminem, and been interviewed by Oprah. They were among the 230 passengers in the Paris-New York flight AF006, which went through a significant turbulence before descent.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

This plane landed twice, three months apart, once at JFK, then at the McGuire Air Force Base, New Jersey. The US military has set Protocol 42, the post-9/11 security procedure, in motion because “today’s Air France 006 flight already landed at JFK more than four hours ago, at the scheduled time of 16:35 hours. But it was a different aircraft, with a different captain and co-pilot. On the other hand, an Air France Boeing 787, with the same reference Air France 006, with exactly the same damage as this one, piloted by the same Commander Markle, co-piloted by the same Favereaux, and manned by the same crew and with the same passengers, in other words the exact same plane as this one you see here, this same plane, then, landed at JFK Airport, but at 17:17 hours on March 10. Precisely one hundred six days ago.” To solve the mystery, a mathematician and a topologist were called in from Princeton.

Every passenger, every crewmember, and even the aircraft, has a double now, one original and the other a copy. The novel becomes an existential thriller when the two versions of the same life meet in real time, and the absence that turned their lives into a multiplying pastiche provides the questions we were born to ask but never dare to ask. When the assassin assassinates his double, when Slimboy becomes Slimboys, when the novelist basks in the glory of the novel he didn’t write, we don’t know when to pause for clearing the fog within and where to look for answers, even though the novelist sprinkles the pages with the possibilities of science fiction and the philosophy of Descartes, parodies of popular culture and pretensions of lofty literature, the kitsch of American television and the dubious certainties of journalism. Or is it all the sorcery of simulation? “Are we living in a time that’s just an illusion, where every apparent century actually lasts only a fraction of a second in the processor of a gigantic computer? And what does that make death, other than a simple ‘end’ written on a line of code?” Maybe Victor Miesel, of The anomaly, provides a believable explanation, and all the necessary epitaphs for the author of The Anomaly: “There is something that always surpasses knowledge, intelligence, and even genius, and that is incomprehension.”

The experimenters of Oulipo are not the artists of unravelling; they are the playful philosophers of the puzzle. The novel is not a genre but a dramatic way of altering our perceptions when they rewrite the inheritance of imagination. Le Tellier, along with the most famous Gallic cult in fiction, Michel Houellebecq, restores the lost renaissance of French culture. “No author writes the reader’s book, no reader reads the author’s book. At most, they may have the final period in common,” reads one of Miesel’s epitaphs. Finding common ground with Hervé Le Tellier is pure exhilaration.