Delhi’s Dhaka Dilemma

Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan's recent telephonic conversation with Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has policymakers in New Delhi worried. That is quite natural, given that Khan's call to the Bangladesh leader comes against a backdrop of recent moves by Dhaka to edge a little closer in its ties to Beijing. With recent developments in relations between India and Nepal and between India and Sri Lanka, one can certainly comprehend why South Block should be concerned.

Perhaps it was the China factor in Bangladesh's recent foreign policy moves that influenced the Pakistani leader to contact his Bangladeshi counterpart. Besides, with diplomacy still in a hiatus in South Asia– and one has to go back to the derailed SAARC summit scheduled to have been held in Islamabad in 2015—the Imran-Hasina conversation could indeed be looked at by observers as the opening of a window for Pakistan and Bangladesh where bilateral ties are concerned. But is it really a window opening?

Relations between Pakistan and Bangladesh, unless one ignores the times when military dictators and their political followers governed in Dhaka, have endlessly been cool. Therefore, when Indian policymakers are worried that Imran Khan raised the Kashmir question with Hasina, they need to travel back in time to the historical position of the ruling Awami League on the issue. Before Bangladesh's War of Liberation in 1971, when Sheikh Mujibur Rahman campaigned on a platform of broad autonomy for what was then East Pakistan, the Kashmir question formed no part of his or his party's politics. Where other Pakistani political parties between 1947 and 1971 kept up the refrain of Kashmir needing to be freed from 'Indian occupation', Mujib and his party went for pragmatism. Kashmir did not matter to the Bengalis, which is why, in independent Bangladesh, it has been regarded, even by the extra-constitutional regimes in the country, as Delhi's internal problem.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

India should, therefore, have little reason to be alarmed by Kashmir affecting Bangladesh's foreign policy perceptions. But where Indian worries about Bangladesh's perceptibly increasing warmth towards China is the issue, the matter is clearly a reflection of the basic tenets of Dhaka's foreign policy. Fundamental to such diplomacy has been the dictum on the nation's diplomacy voiced by Bangladesh's founding father Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in early 1972 that the new nation's foreign policy would be based on friendship for all and malice towards none. It is this Lincoln-esque philosophy that has defined Bangladesh's diplomacy, especially in Mujib's era—and in the years his daughter Sheikh Hasina has been in office.

Dhaka would obviously not like to be tagged to Delhi in the exercise of its diplomacy, a point that was initially made clear in February 1974 when Prime Minister Sheikh Mujibur Rahman chose to travel to Lahore for the Islamic summit convened by Pakistani leader Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. It was a move that left Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi rather surprised. At the same time, when some of his own cabinet colleagues suggested that Mujib consult Indira Gandhi about his attendance at the OIC summit, he firmly put down the suggestion. He was grateful to Delhi for its unwavering and historic support to the Bengalis in 1971, but he was careful not to be seen as being under its influence. His nationalism precluded any such possibility.

The China question has long been part of any study of Bangladesh's history. Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai not only sided with Pakistan in the 1971 war but subsequently also vetoed the country's entry into the United Nations. At the time, the Mujib government maintained a diplomatic silence, preferring not to fall for the temptation of condemning Beijing for its action. Mujib, ever the pragmatic politician, was fully aware of the fact that sooner rather than later, Dhaka and Beijing would establish diplomatic relations. Indeed, such an establishment of ties was in the works by the time the Bangladesh leader was assassinated. The Chinese recognition of Bangladesh's independent status came a few days later.

While Dhaka's diplomatic priorities are the issue today, Hasina and her government are under pressure on many fronts, particularly in light of the coronavirus pandemic. The economy is tottering, with industries shut down and workers losing jobs. The government has come forth with stimulus packages geared to keeping lives afloat. Even as it has been handing out relief goods to people newly pushed into poverty, it must now cope with the floods now ravaging the country. Domestic politics must also tackle the corruption that has been eating into the nation's social fabric.

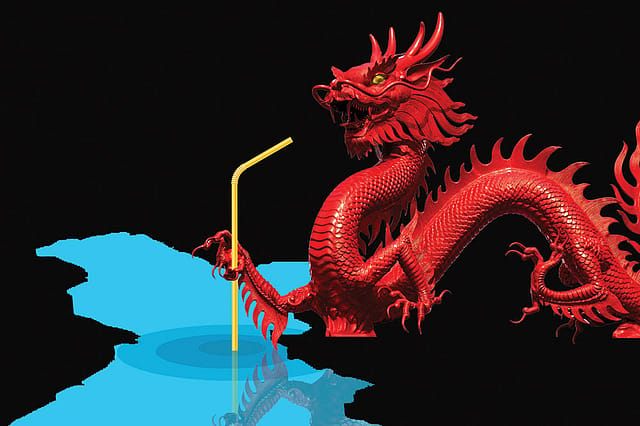

Bangladesh's ties with China are in large measure a reflection of its foreign policy principles. Indian diplomatic quarters are quite upset that Dhaka had nothing to say on Galwan. That was again prompted by Dhaka's need to keep a balance in relations with both Delhi and Beijing. The country's economic ties with its two larger and powerful neighbours matter in its domestic affairs. As a geographically small country, one poised to graduate to a middle-income nation, it is in its interest to see to it that both India and China respect its position.

But yes, there are the worries in Dhaka. On the issue of China's Belt-and-Road Initiative, a high degree of pragmatism will be called for in that, historically and geographically, India and Bangladesh are bound to remain close—as a minister recently pointed out to the Indian high commissioner in Dhaka. Bangladesh has refrained from commenting on the recent occurrences in Hong Kong and on the Uighur issue. Extra caution? Perhaps. But neither has Dhaka officially registered its displeasure at Delhi's failure to see a treaty on the sharing of the Teesta waters through. Citizens' perceptions in Bangladesh cannot be ignored: If Dhaka has given Delhi the all-clear on the trans-shipment of goods through Bangladesh to its northeastern states, it is beyond understanding why no steps have been taken towards a settlement of the Teesta issue.

Bangladesh's cooperation with India and China has straddled the economy and defence, which ought to be a sign of a full playing out of its diplomatic objectives. There should be no reason for alarm here. It is Bangladesh's enlightened national interest, without detriment to any of its neighbours, that is the unmistakable priority in Dhaka today.