When India gets a slice of the American dream

YOU CAN TELL a lot about a country by its attitude to holidays. Much of Europe takes off for the whole of August, while the US takes around two weeks a year. Santosh Desai wrote brilliantly about pre-liberalisation Indian holidays while now Indians on vacation are seen the world over: from Japan to the Lake District, UK, sometimes seeking out Bollywood locations, or forming the largest group crowding around 221B Baker Street.

As a teenager I was consumed with envy when school friends went on holiday to Spain (then still ruled by General Franco) or someplace where they could swim in a warm open air pool and get a tan. We, on the other hand, went to the west coast of Scotland where my father went fishing for trout while we swam in cold lochs and took long walks, wrapped in warm clothes.

Holidays are a major focus of the year, carefully discussed and planned, where we seek new experiences and memories, perhaps for culture, gastronomy or hanging out with friends and taking a break from our daily routines. I find all these in India but sometimes, not too often, I'm persuaded to go elsewhere. This summer we are on the east coast of the US, doing all of the above.

Our first stop is New York, a very desi city for me. All my friends here are Indian academics, curators or writers, so meetings are scheduled well in advance, usually around meals. I'm glad we ate at some of the top dollar restaurants before the pound fell so steeply. Fortunately, some of my favourite gastronomic experiences, the Nutter Butter peanut cookie and the giant Oreo at the Bouchon bakery, are well within reach. The name of the Whitby Hotel may evoke Dracula but its contemporary elegance, seen in every detail and the glamour of paparazzi hovering by the door, makes it a quintessential New York experience. For restaurants with views, it's hard to beat that of Central Park from Robert's, and for a New York buzz and great cocktails, Augustine hits the spot, especially in the company of the fabulous 'Ritzy Prof', a true New York Marwari. The week ended with a dinner of Portuguese food and too much Vinho Verde with an old friend (and Open contributor) who, I would have said when we met at university, was the last person I could imagine ending up living in the US.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

I am as bored hearing about bad American food as I am of being told the same about what British people eat. All I can say is, 'Where have you been going?' The vegetarian and vegan options in New York are brilliant. Crown Shy hits all the buttons with its salads which are as beautiful as they are delicious, a mixture of grains, nuts, fruit and vegetables, showing supreme restraint and great confidence and technique on the part of the kitchen.

Our next stop, amid the eating, was Mrinalini Mukherjee ('Dillu') at the Met Breuer, where we were walked through by the curator, viewing her incredible work that has been brilliantly and deservedly reviewed in the New York Times and Times Literary Supplement. Dillu's huge ropework sculptures were long neglected—one of their owners is reputed to have used one for a hammock—but now their sculptural majesty and form are in plain view. The exhibition eschews pedestals in any sense in favour of sculptures, displayed in a room divided by curtains, allowing the viewer to walk chronologically through her oeuvre. The knotted fibres made my hands ache in sympathy but the folds and the impressive forms recall classical Indian sculpture yet also evoke craft and handiwork. The grace and blatant sexuality of the sculptures clearly impress visitors to the Breuer irrespective of their background or knowledge of India.

After the Met, where else but Coney Island, which I finally visited, though dodged the rides and helter-skelter, but enjoyed strolling on the boardwalk, wondering how on earth anyone could eat 87 hot dogs in the Nathan's competition, then walked the Woody Allen locations of Brighton Beach to gawp at the produce in the Russian shops and delis.

A couple of bookshops to pick up some reading and then we set off for Maine, staying on an island in Casco Bay with old friends. It took me back to my youth as it's like Scotland with better weather and more luxuries though the sea, which is, after all, straight across the Atlantic, is just as cold as over there.

I didn't have time to visit the season of films at the Lincoln Centre which are curated to accompany Shanay Jhaveri's new edited book, America: Films from Elsewhere, for which I wrote the Bollywood chapter. It was wonderful to rewatch old favourite films such as Subhash Ghai's Pardes (1997), to see glamorous America overwhelming the second generation antihero, while the hero, SRK, rescues the heroine, Ganga, and hear super-patriotic songs like 'I love my India'. Imtiaz Ali's Love Aaj Kal (2009), has a mostly negative image of the US, preferring London and Delhi, but above all post-Partition Calcutta, for true passion and romance. Dhoom 3 (2013) uses the dramatic cityscape of Chicago for its thrills and spectacle.

Hindi films set in America have developed a new sub-genre of the Islamicate film, a group of genres that show the culture and social norms of India's Muslims. This is the post-9/11 group of films that shows radicalisation and Islamophobia but in America rather than India, so the antagonism does not involve other Indians and puts the issues on the global stage. The most famous of these are Kurbaan (2009), My Name is Khan (2010) and New York (2009). They show radicalised Muslims contrasted with 'good Muslims', now young Indian Americans, very different from the loyal Pathans and Rahim or Abdul Chachas of the old.

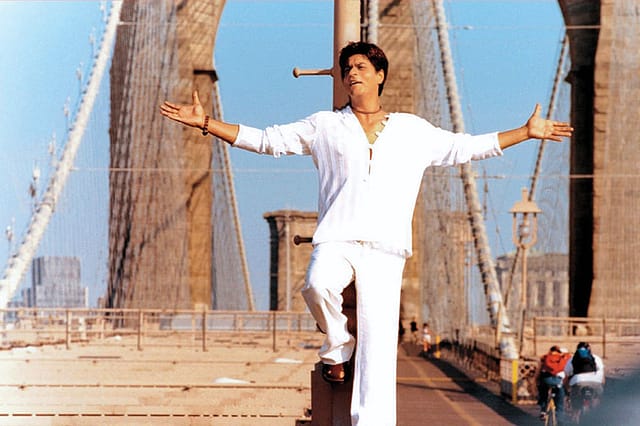

Karan Johar shaped the image of New York for many Indians with his use of iconic locations, including the Brooklyn Bridge, Central Park, Columbia University and railway stations. Kabhi Alvida Naa Kehna (2006) concerns marital breakdown in a weepy, while his productions Kal Ho Naa Ho (2003) and Dostana (2008) explore gay relationships through comic misunderstandings, whose pioneering nature shouldn't be underestimated because of their indirect angle.

The gorgeous Sridevi's English Vinglish (2012) shows an Indian housewife whose family loves her but don't respect her as a non-English speaking housewife. She steps into the outside world in New York as she secretly enrols in English classes where her relationships bring her as much freedom and respect as her learning the new language does with her family.

These films, which look at Indians enjoying glamour and wealth but often testing family relationships, mark a particular time in the history of Hindi cinema as concerns have shifted to films (and series screened on streaming services) which examine Indianness in the post-2014 context. These are set in other places—more realistic locations within India itself and on its borders—or in other times, such as historical conflicts. Perhaps, now so many Indians are successfully settled in the US that Bollywood's concerns have shifted to domestic issues rather than the international: who we are at home rather than who we are abroad.