The Class Test

When the UPSC examination is conducted onscreen

Aditya Mani Jha

Aditya Mani Jha

Aditya Mani Jha

Aditya Mani Jha

|

16 Aug, 2024

|

16 Aug, 2024

/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/ClassTest1.jpg)

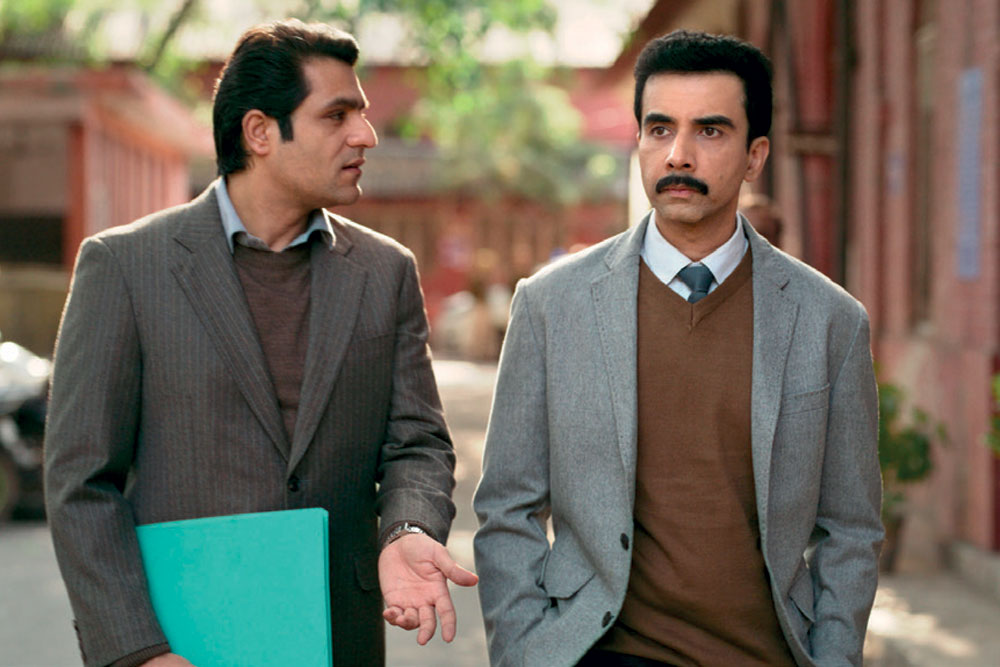

Vikrant Massey in 12th Fail

On the opening episode of The Viral Fever’s (TVF) Hindi web-series Aspirants (streaming on Amazon Prime), there is an scene where a well-meaning teacher, SK in Delhi’s Old Rajendra Nagar area (a hotbed of UPSC-prep students) is delivering a pep talk to his new students. He is trying to tell them—in the nicest possible way—that this is not an examination for the faint-hearted. As we gradually discover, ‘SK Sir’ (aka Shwetketu Jha, played by Abhilash Thapliyal) was once an aspirant himself, just like the many Rajendra Nagar diehards he is coaching right now.

A heartfelt dialogue in Aspirants goes, “This is old Rajendra Nagar, you’ll find infinite stories of hopes and desires and disappointments here. A lot of stories begin and end right here, but some… only some go on to create history. This is an examination that will extract everything from you, not just physically but mentally as well. First attempt gone, second gone, third gone… soon you’ll look back upon this time and discover six years of your life extinguished.”

Rajendra Nagar is currently in the national spotlight for unfortunate reasons. On July 27, three students drowned in a waterlogged basement in Rajendra Nagar, at a centre owned and operated by Rau’s IAS Study Circle, one of the biggest UPSC coaching firms in India. This, along with the recent Puja Khedkar fraud allegations, means that the whole system of selecting and appointing IAS officers is currently under national scrutiny. And if we look at Indian films and TV, this is reflected in some very popular stories over the last three-four years. Vidhu Vinod Chopra’s comeback film 12th Fail (based on the real-life underdog story of an IAS officer from Chambal, Madhya Pradesh) became a sleeper hit—there’s a real wall in Rajendra Nagar with graffiti showing the film’s main characters and their dialogue. TVF’s Aspirants is one of the more successful and well-received Indian shows of the last few years. Its recent spinoff SK Sir ki Class (available on YouTube) has also garnered great reviews, with Thapliyal reprising his role as SK Sir, the Unacademy teacher (significantly, Unacademy sponsors both Aspirants and SK Sir ki Class).

A common feature in all three stories is the idea of the UPSC examination being a bridge to narrow the gap between haves and have-nots in India. Once you become an IAS officer, your caste, gender and religion matter much less than they ordinarily would—or so goes this line of thinking. According to Apoorv Singh Karki, who has directed Aspirants, this is an especially important aspect in a deeply unequal country. “The exam itself is an equalising force,” says Karki. “Because the only way you are going to succeed here is through your own hard work and talent. There are no shortcuts or ‘cheats’ here. Your knowledge cannot be one-sided: an IAS officer has to have knowledge of each and every sector, from agriculture to manufacturing and everything else. While taking any decision, he or she has to consider all kinds of factors, consider the welfare of each and every citizen.”

Karki’s own story is like something out of a Bollywood underdog story. After years of narration sessions with producers, Karki had little to show for his efforts by 2014. And by then, his parents had suggested that he should have a backup plan—prepping for the UPSC entrance examination. Few things are as classically Indian as parents urging you to study more, just a little bit more, especially in service of a competitive exam.

“By 2014 I had already been struggling in Bollywood for some time, with very few prospects materialising,” Karki recalls. “So, my parents and I decided that I should sit for the UPSC examinations. That is when I saw and experienced the life of students in Rajendra Nagar. Sadly, I failed the prelim examination but soon after that, I started working with TVF at their Delhi office.” Karki continued to work with TVF on their online videos and web series (in that era, TVF’s parody videos were all the rage on the internet). In 2019, TVF decided that it would create a show about UPSC aspirants. It was common knowledge around the office that Karki had first-hand experience of this world. In this way, he found himself donning the director’s hat for the first season of Aspirants. Last year, the show completed a well-received and poignant second season.

Released around the same time as Season 2 of Aspirants, the box office success of 12th Fail came as a surprise to many Bollywood insiders and analysts alike. This is the era of big-screen spectacles, with genres like action-adventure and sci-fi dominating the cash registers. 12th Fail on the other hand is a small, self-contained story with zero franchise potential, with a leading man (Vikrant Massey) who is far from the square-jawed, barrel-chested stereotype of the large-screen hero. The fact that it earned over `69 crore worldwide on a `20 crore budget has to do with the film’s approachability and its serendipitous timing.

There’s much to be said for being at the right place at the right time, and 12th Fail did just that. The film opens with a sequence showing the protagonist cheating during his Class XII exams. Considering how many national-level examinations are being cancelled due to suspicion of paper leaks these days—it is little wonder the film struck a chord with students and parents. Ironically, the more people lose their trust in the education system, the more stories like 12th Fail will gain traction. Think about it this way: if you knew beforehand that a game you’re playing is rigged, wouldn’t you be interested in a story that tells you how to trick the tricksters?

According to Anurag Pathak, who wrote the Hindi nonfiction book 12th Fail (on which the film is based), there are solid structural reasons for the way Indian audiences have embraced the story of Manoj Kumar Sharma, IAS. During a telephonic interview, Pathak says, “People identify with Manoj’s story because in a poor country like ours, very often people don’t even get a real shot at their dreams. If you ask your parents, they will tell you that their generation didn’t have a fraction of the opportunities youngsters have today. So, when the audience today sees a story like Manoj’s, it affects them in a meaningful way. How often do you see a poor, well-meaning, Hindi-speaking man in the big city sticking to his strengths despite circumstances, despite setbacks— and actually winning at life in the end?”

Manoj’s character in 12th Fail emphasises the value of teamwork, another message that resonates with Indian audiences because “we are not an individualist society like the West”. In its gushing portrayal of ‘unity in diversity’ and the camaraderie displayed by Manoj and his friends (who belong to different castes and regions etc) 12th Fail resembles feel-good sports dramas like Chak De India and Gold. Significantly, both these genres are preaching the same lesson to the audience: rise above your differences, help build our nation together.

If you look at the way IAS/IPS officers have been portrayed in Hindi cinema down the years, you can see this pattern of self-sacrifice and ‘rising above petty concerns’ being repeated. Often, this pattern is offered up as a break from the usual ‘displays of power’ on the part of the IAS/IPS officer. In Prakash Jha’s Gangaajal (2003), Ajay Devgn’s Bihari IPS character commits career hara-kiri again and again by publicly contradicting his seniors as well as Bihar’s political overlords. Dibakar Banerjee’s Shanghai (2012) sees Abhay Deol as the bureaucrat Mr Krishnan siding with corrupt politicians to push through an infrastructure project that is going to displace thousands of poor people. Of course, he reverses course (once again, sacrificing career progression, as the film’s climax reveals) after his conscience pricks him—and he is guilted into seeing the dark side of the ‘nation-building’ unfolding around him. There is either extreme power or extreme conscience—IAS officers in Bollywood are seldom offered middle ground. In Shaadi mein Zaroor Aana (2017), the story of ex-lovers who are now both bureaucrats is taken to its logical endpoint. Here, the man is a magistrate (an IAS officer ie a central-government bureaucrat) who explicitly punishes his ex (a PCS officer, ie a state-level bureaucrat) using the law. She has been accused of taking a bribe. He tells her clearly that had she not dumped him, she would not be suffering today. He reverses course after realising that she is being framed by her opportunistic seniors.

Aspirants also does not glorify the ‘hustle’ of competitive examinations. More importantly, the three central characters, UPSC aspirants all, are also concurrently shown as adults, leading their (very different) lives. A running gag in the world of Aspirants is students from different parts of the country having drastically different comfort levels with English. A line from 12th Fail, in this context, makes an important point about the dominance of English-medium students in the UPSC entrance examinations.

“Do lakh Hindi medium vidhyarthiyon mein kewal 25-30 hi ban pate hain IAS” (Out of 200,000 Hindi medium students, only 25-30 become IAS officers). It goes without saying, this ratio is alarming and deflating if you’re a Hindi-medium student. This is why the protagonist Manoj in 12th Fail is told that his success is a triumph for every Hindi-speaking student in Rajinder Nagar.

“Jis din hum mein se kisi ek ka jeet hota hai, toh Hindustan ke karodon bhed-bakri ka jeet hota hai (The day any one of us wins, crores of ‘sheep’ across India win), says a character in 12th Fail. ” The ‘bhed-bakri’ (sheep/goat) framing of the line is especially interesting because it hints at two possibilities. One, that there is something dehumanising about lakhs of people competing for a few hundred seats. Two, in this world of competitive exams, it is extremely easy to become ‘sheeple’ — one of the herd, and fall to peer pressure. The Hindi-medium students are especially susceptible to this phenomenon because they are less likely to have parents, friends or acquaintances who can give them relatable, targeted advice on exam-related matters.

When I was watching SK Sir ki Class recently, it struck me that idealism— its inception, as well its end—is a big theme in all of these UPSC stories. There is the doomed idealism of one’s early twenties, of course, all fire and brimstone about issues of social justice. But these stories also talk about a distinctly Indian strain of idealism, the kind that pushes back against the “kuch nahi badlegaa” (nothing will change) pessimism of our parents and teachers. During my interview with Karki, he shrewdly diagnosed this idealism as one of the few routes to rapid development in a country like India.

“If you look at the middle-class and working-class students who look at the UPSC with a sense of prestige…. a lot of them come from small towns and villages,” Karki says. “They want to return home as an IAS or an IPS officer and contribute to the welfare and development of those areas. For city-dwellers like you and me it is not easy to comprehend the problems that those areas face on a daily basis.”

Stories like 12th Fail or Aspirants will likely receive a bump in viewership thanks to events in the current media cycle. What’s more important, though, are the lessons that ordinary Indians derive from these stories. Whether you end up becoming a bureaucrat or a magistrate, the story of how you arrived at the chair ends up defining, for better or worse, what you do once the chair is yours.

About The Author

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover-Shubman-Gill-1.jpg)

More Columns

Author Thomas Suárez presents peace framework for the Palestine-Israel crisis Ullekh NP

Shubhanshu Shukla Returns to Earth Open

Nimisha Priya’s Fate Hangs In Balance, As Govt Admits It Can’t Do Much Open