Second Coming

Inspirations, adaptations or mutations? Does it matter?

Bhakti Shringarpure

Bhakti Shringarpure

Bhakti Shringarpure

|

14 Mar, 2019

Bhakti Shringarpure

|

14 Mar, 2019

/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Secondcoming1.jpg)

GULLY BOY, BOLLYWOOD’S first feature film about a young rapper emerging from Mumbai’s slums, has opened to great critical and popular success. A close friend was not happy when I said that it seemed influenced by the Eminem film 8 Mile (2002), which told the story of a White Detroit rapper overcoming poverty and domestic abuse to find his voice. Though we both thoroughly enjoyed Gully Boy and found it excellent on so many levels, it seemed that, for her, calling it ‘adapted’ or ‘inspired’ sullied the film’s quality.

I wondered about her negative reaction, because adaptation has always been integral to cinema. ‘Adapted screenplay’ is a legitimate, mainstream awards category, though the relationship is somewhat limited to book-to-film. Still, a fluid exchange between texts and contexts, stories and narratives, is part and parcel of filmmaking. Everything ranging from books, short stories, fairy tales, plays, music, video games, films and songs get adapted to the big screen.

The 2002 Hong Kong film Infernal Affairs was adapted to a Boston milieu when Martin Scorsese directed it as The Departed four years later. No one was particularly upset. But the process is not as seamless when it is the other way around. Indians have a particularly complicated (and mostly negative) relationship with Bollywood’s habit of sourcing material from the West.

My generation grew up with the most embarrassing iterations of Bollywood copying, especially when it came to songs. Lists found online are easily able to cite as many as 40 or 50 examples: Mere Rang Mein Rangne Wali and Aate Jaate in Maine Pyar Kiya were lifted from Europe’s Final Countdown and Stevie Wonder’s I Just Called To Say I Love You, and Akele Hai To Kya Gam Hai from Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak, taken from Return To The Alamo by The Shadows, are just few of the songs I remember from childhood that had unabashedly copied. For the sake of this article, I’ll leave you with the memory of India’s first rap hit: Baba Sehgal’s Thanda Thanda Pani, which I’m going to translate as Icy Icy Water just to remind us of yet another copycat, Vanilla Ice, who ripped off Ice Ice Baby from Queen’s Under Pressure.

There were also versions of Hollywood films that often got remade: Dil Hai Ki Maanta Nahi (1991) was a remake of It Happened One Night (1934); Akele Hum Akele Tum (1995) remade Kramer Vs. Kramer (1979), and Dostana (2008), used I Now Pronounce You Chuck and Larry (2007) as its template. Examples abound, and mocking memes and blogs online are evidence of where people might stand on this. With copyright laws getting stricter and multinational deals becoming the new normal in India’s entertainment industry, however, these sorts of things have become much harder to pull off.

But the ’80s and early ’90s were very different for us city kids growing up in middle class or upper middle class families; the proliferation of TV channels, and films and music from around the world that came with the liberalisation policies of 1991 had not yet happened. For those of us who cherished buying cassette tapes of American or European music or watching the select few Western films that came to theaters or on VHS, finding out that Hindi songs were copied or films were ripped off was always embarrassing. It was never clear why this happened, given the extraordinary supply of stories, musical genres, creativity and talent in India. Part of the problem was the relationship with the cultural metropole, which was always located in the West for teens studying in English medium schools, mostly wearing Western clothing and worshipping pop idols and film stars abroad.

Remakes have also gained stature. And the aftertaste of shame that characterised the old days has mostly disappeared

Bollywood’s ripping-off tendency produced a deep shame, not so much because it felt unethical, but because localising Western tunes and movies somehow cheapened the precious relationship that had been built with the West itself and that was deemed so important if the well-colonised younger generation was to feel cool or hip at all. In a way, Westernisation, inherited from colonial rule and carried forward by American cultural imperialism, was always what marked class divides, and it seemed in the interest of the Westernised ones to keep those divides intact. Part of that game meant turning up your nose at Hindi films, listening only to Western music, not using local slang in your English, looking down on those who didn’t show fluency in these references, fighting with parents who found all this confounding, trying to shave off the hard Ds when speaking English, following Hollywood fashion trends not the Bollywood ones, and so on and on and on the game went.

But thankfully, we grew up and learnt a thing or two.

A couple of decades later, with transnational flows of capital and culture becoming commonplace and a vast global network of ideas, communication and artistic exchange now available, many of these discourses of coolness, hipness, language, culture and shame have been reversed. Those foolish tendencies to idolise the West have even started to fade.

Film remakes and adaptations have also gained stature, and the aftertaste of shame that characterised the old days has mostly disappeared. Coppola’s Godfather trilogy was unabashedly remade as Sarkar, Sarkar Raj and Sarkar 3 and adapted to Mumbai mafia context; Vishal Bhardwaj’s powerful Shakespeare adaptations with Maqbool, Omkara and Haider have garnered praise and critical acclaim; and adapting Chetan Bhagat’s pop novels has been a successful endeavour, as well. Yet these tend to be high-end, intellectually rigorous films that openly engage the discourses of adaptation by embracing the textural and creative challenges of localising the original source material and experimenting with multiple mediums and registers of storytelling.

WHAT DO WE DO with the sillier ones—the less intellectual and the less self-conscious films that tend to be loose and lax with how they go about layering their work with echoes of Western shows or films? What about the four single friends structure of the recent series Four More Shots Please!, or the replication of the Dead Poets Society environment in Mohabbatein, or the Bonnie and Clyde motif in Bunty aur Babli? Are these copies? Inspirations? Adaptations? Mutations? Knock-offs? More importantly, what do we do when there are simply echoes of some other text or a vaguely derivative quality? For example, watching Vivek Oberoi play Mr Dhawan in Amazon’s fabulous cricket drama, Inside Edge (2017), brings about a kind of déjà vu. I can’t pinpoint where this character originates, but I know it is not organic to the setting it lives in. The truth is many of these shows and films only use aspects of the original or borrow something structural and sometimes, the source material is lost under several unrelated plot lines.

The lines between adaptation, intertextuality and intermediality have grown increasingly impossible to parse through

This is precisely why the debate around Gully Boy and 8 Mile is muddled and so very patronising. The trailer had, after all, made it seem very close to 8 Mile, despite the fact that 8 Mile is a marginal, small film compared to Gully Boy in terms of budget and the multitudes it will reach. When the social media noise around Gully Boy resembling 8 Mile reached me, it was entirely comprised of knee-jerk reactions. Accusations were being hurled and it was being called a rip-off, a wannabe take, a copy, etcetera. Mash-ups of Gully Boy and 8 Mile have already shown up online.

Gully Boy indeed owes a debt to 8 Mile, but instead of being a tale of an artist coming of age, Gully Boy goes for the rags- to-riches story arc. Early scenes do show Murad, the Dharavi rapper, coming to terms with his talent, gaining confidence, validation and community just like in 8 Mile, but the second half is focused on winning a contest that will make him rich and famous.

Aspects of 8 Mile interspersed quite skillfully: the abusive and emotionally draining domestic situation; the unpredictable, self-realised and spunky love interest; the ragtag gang of somewhat uncool friends; the attempts at an honest job interrupted by the desire to write and rap; saving the mother from her violent husband; and the poet-mentor figure who has already garnered local respect as the protagonist’s pillar of support. The love triangle of 8 Mile has been reversed with Murad courting two women instead of the female lead Alex (played by the late Brittany Murphy) courting two men. More importantly, however, is the ways in which Murad’s coming of age seems inspired by Jimmy’s in 8 Mile with the early choke at the rap battle followed by scenes of him writing and practicing with guidance from his friend MC Sher.

The rip-off accusations stem from the truly unfortunate overlaying of the dynamics of 8 Mile’s rap battles in Gully Boy. The specificity of the lyrics used in the rap battle finale are also inspired by 8 Mile with the central theme being that Murad wins by owning up to his own poverty and lack of coolness and disses the opponent by calling him a spoilt rich brat who lives off his dad’s cash. Gully Boy does a tremendous job of integrating aspects of 8 Mile, while redressing it beautifully to fit the Mumbai scene. The most original aspect of the film, after all, is the use of Mumbai’s particular street language and its truly extraordinary soundtrack. Additionally, several other plots, some of them terribly overwrought, also populate the film and move it farther and farther away from 8 Mile. The unnecessary plot with rich NRI, Sky, allows Murad to make his first music video but given the video’s gritty, local quality and the crew’s digital proficiency, it seemed that Sky’s resources were not needed in the first place. She is almost meant to complicate Murad’s relationship with girlfriend Safeena, and once again this is unnecessary given how complicated Safeena’s family dynamics already are.

Whichever way you cut it, adaptations are always plagued by anxiety, and given Bollywood’s copycat history, there is plenty of shame to go around. Oddly, director Zoya Akhtar has not openly acknowledged any filmic influences or inspirations at all. There are several iterations of the rapper-makes-it film, and Akhtar choosing Curtis Hanson’s 8 Mile over Get Rich or Die Tryin’ or Hustle and Flow or Notorious as inspiration should not be seen as a problem.

It might finally be time to joyfully engage the rich and generative flow of art and ideas, especially as the binaries between original and borrowed blur quickly with the Internet. Even in academic adaptation studies, the debates between fidelity and infidelity, authenticity and derivation, and the lines between adaptation, intertextuality, intermediality have grown increasingly impossible to parse through. But in India, these relationships are stained by colonial histories, and the dynamics of cultural, linguistic and artistic creations carry the deep weight of inferiority complexes left over from uneven relations between the West and the rest. Bollywood, its fans and its detractors have been burdened by these for far too long. Let’s not forget that Bollywood has now started to become a source of inspiration in American entertainment and so the playing field is altering radically and rapidly.

Eventually, it all boils down to the quality of the final product. When it is successful (for reasons too ubiquitous and too numerous to count) we say it works. But when it fails, then the original text is touted as better and the adaption exemplifies the failure. Luckily, these debates are quite irrelevant with a film as brilliant and hard-hitting as Gully Boy.

Also Read

Ranveer Singh: A Hero of Our Time

Ranveer Singh: The Hybrid Star

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

MOst Popular

3

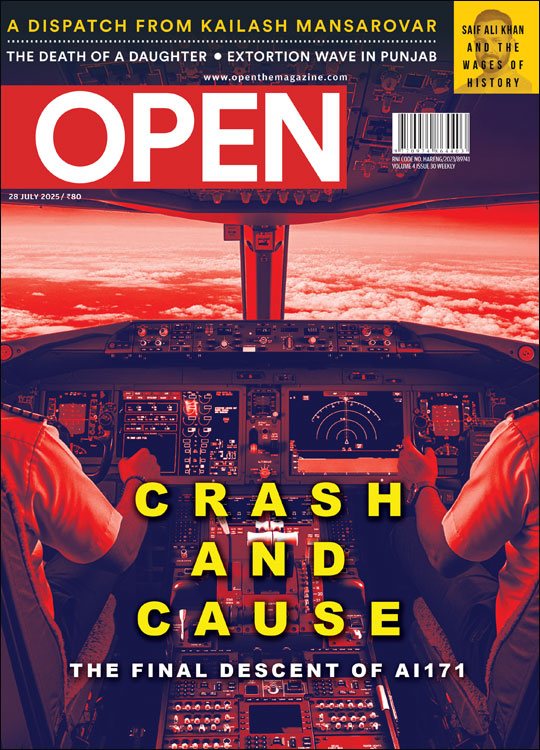

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Crashcause.jpg)

More Columns

Bihar: On the Road to Progress Open Avenues

The Bihar Model: Balancing Governance, Growth and Inclusion Open Avenues

Caution: Contents May Be Delicious V Shoba