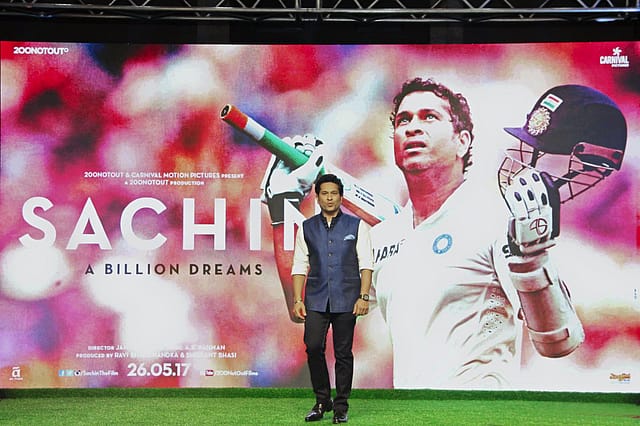

Sachin: A Billion Dreams Movie Review

Because his extraordinary career in cricket spanned 24 years, Sachin Tendulkar is our 'Peter Pan' figure, a genius of a boy who never turns into an adult, and whose free spirited image grips two generations of Indians in their growing up years. Many of the pictures and videos of Mr. Tendulkar are of his childhood; a curly haired child crouching in a copy book stance with a small bat, a boy nursed into the game by his adoring half brother, Ajit, loved and spoilt by his much older siblings, yet respectful of his elders, and one who was made to feel secure enough to weld his passion and his profession into a single whole at the age of 16; an age when most young Indians are buried in their school books, without the slightest idea of what they are going to do next.

It is this aspect of Sachin's persona that the movie 'Sachin: A Billion Dreams' captures well and hangs on to for the duration of the documentary. Strange as it may seem, it is the use of the cricketer's own photos and home videos that is director James Erskine's trump card in the film. Born into a family of a middle class Maharashtrian scholar – the home of the poet, novelist and Professor, Ramesh Tendulkar – Sachin was fortunate to be extensively photographed and remembered by charming anecdotes from his extended Shivaji Park family. As he turned into a husband and father himself, he evolved into an affectionate and respected elder like Ramesh, except dramatically transformed, like a Hindu God, from the academic seclusion of his father's world, to an international sports celebrity.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

At some point in the film, Sachin explains his religious faith, saying that when he looks at the auspiciousness of events in his life, he sees a guiding hand in the destiny that has favored him so extravagantly. The movie keeps us trapped in this idyllic, fairy tale like story of a modern Indian deity, by demonstrating a parallel with the story of India's exponential economic growth during the Sachin years, and the dramatic events that took place in Mumbai, the city of his birth, during his cricketing days. Visuals of the trauma of 26/11, the hysteria of the World Cup final of 2011, the annual immersion of Lord Ganesh in the Arabian sea; all these get inextricably linked with the story. The associative nature of human memory rewinds the images, connecting them to us in time with Sachin's batting milestones.

Other episodes and relationships that might recall disturbing memories, and which negatively affect the desired 'Peter Pan' imagery, are either erased, brushed off or gone over quickly. The match fixing period, for example, depresses Sachin, but he does not brood about it, analyze it, ask moral questions of its perpetrators, refer to specific matches where he may have sensed, as a reflexive and instinctive sportsman, something going horribly wrong.

But the most extraordinary exclusion in the story is the one about his childhood buddy, the prodigiously talented batsman, Vinod Kambli. He is virtually deleted from the movie. Where are all the lovely stories of them playing together, like the one where they batted endlessly in a school game, ignoring the instructions of the coach to declare the innings closed? How did one friend climb the stairway to heaven, and the other just fall off a ladder? Was it anything to do with their very different social backgrounds? Does cricket divide us by class and social station, more acutely than in other sports? The film, unfortunately, has no use for any of these awkward questions.

Iconography is clearly the single largest purpose of 'Sachin: A Billion Dreams'. As in the building of a brand, memorabillia is an important tool in this exercise, and James Erskine's film is acutely conscious at every moment about nursing the memories of the Sachin generations to which so many millions of us belong. But only the nice ones, through pleasant reminders like the bats and pads and superstitions of Sachin, his wonderful commercials for a myriad consumer products, and his picture perfect family that runs in an endless loop through the film.

On the other hand, this film is supposedly a documentary, a genre that ought to repudiate iconography, lest it turn into a public relations spiel, or even, God forbid, propaganda.