Sudhir Patwardhan: The People’s Painter

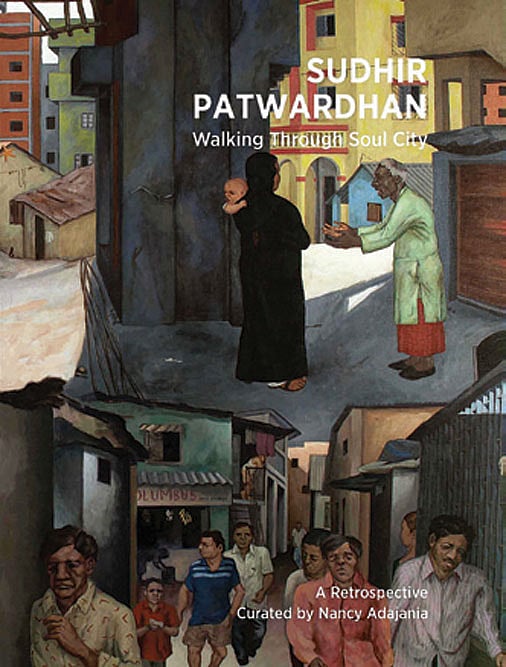

Sudhir Patwardhan’s Walking Through Soul City at the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA) was one of the last major exhibitions in Mumbai before Covid-19 paralysed the city in 2020. Curated by Nancy Adajania, the retrospective had taken up the entire museum building, each segment unusually designed to display his art thematically rather than chronologically. To fit the moment, The Guild art gallery, which had presented the NGMA show, was supposed to unveil the most comprehensive book yet on Patwardhan’s five-decade long career. Somewhat delayed due to the pandemic, Sudhir Patwardhan: Walking Through Soul City (The Guild; 496 pages; `6,000) is finally here. When we meet the artist at his home in Thane, Mumbai he is by turns calm and introspective. Working on the book for the past six months has meant Patwardhan has had to sift through his oeuvre, starting from 1970 when he first began painting. Now 73, he admits feeling detached from his older works. “One is not sure how to relate to the person who painted these images,” he says with a laugh. “I know it’s me, but most of these works have long been left out into the world. Neither can I recreate that feeling in my art nor in my own self.”

In his youth, he was very much a flaneur. Commuting on the crowded Mumbai local at rush hour was both a necessary evil and unbridled joy. He would religiously visit the Jehangir Art Gallery followed by a cup of tea at an Irani cafe in Kala Ghoda or simply walk and take in the sights and sounds of the Maximum City that has been his object of love and enquiry since the start of his career. Today, in the digitalised age, revisiting his iconic works—such as Irani Restaurant (1977), The City (1979), Train (1980), Accident on May Day (1981), Street Corner (1985), People on a Bridge (1996) and Lower Parel (2001)—can evoke memories of a bygone era. His art evokes the Marxist anxieties of the 1978 movie Gaman’s quintessential Bombay song ‘Seene mein jalan’.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

In her curatorial essay in Walking Through Soul City, Nancy Adajania writes that his art conjures up “the most striking painterly embodiment of the crises of metropolitan life and the traumas of urbanisation in contemporary India.” Although his lifetime’s work can be seen as an unstoppable anthology of Mumbai’s hope, aspiration and struggle, he has also documented the most tumultuous moments in the city’s recent history. From the 1992 riots to the 2020 migrant crisis, Patwardhan’s empathetic eye has tirelessly drawn attention to political conflicts, economic inequalities and social injustice. Notable paintings from his oeuvre, like Kanjur (2004), The Clearing (2007) and The Emergent (2012) to name a few, memorably capture Mumbai at the cusp of urban renewal. The Emergent, particularly, is symbolic of a city in transition. A perfect coming together of the old and new and haves and haves-not, it depicts a gleaming building with a glass facade flanked by hutments on all sides.

Much of the vintage City of Dreams that was once Patwardhan’s favourite stomping ground is fast vanishing. “I have been trying to come to terms with this transformation for years now,” he concedes. “Essentially, an artist is responding to the present. The past is past and you cannot hold on to it. Since I have lived through the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s, I and many others of my generation have memories of a time that marked an epoch in Mumbai’s history. I can say that we have lost many of the qualities that made this city great. Now you have a more gentrified atmosphere with gated communities and tall towers but there was a time when Mumbai was a much freer and fluid town. Everyone was welcome. The chawls had a community culture. You could ride in a kaali peeli (taxi) and roll down the window while crossing Marine Drive to get some fresh air. Today, you travel in Uber and the windows are all rolled up. You are so removed from social realities. Even if you decide to peek outside, there’s a different city that looks back at you.” Before you label him an incurable romantic, he adds a disclaimer, “But it doesn’t mean that the 1970s and ’80s was some ideal period. To me at least, being nostalgic about it makes no sense.”

Spend a few hours in Patwardhan’s company and it becomes clear that he’s always been a painter of people more than places. Even though the landscape, architecture and street life of Mumbai has found vivid expression in his works over the decades, it is figuration and the human condition that remains the cornerstone of his art. Committed to Marxism from a young age, he was once torn between becoming a revolutionary so that he could work towards a more equitable society and being an artist. Instead, he became a doctor. He explains, “I have always had this feeling where I ask myself, ‘Is this enough?’ Throughout my career, I have tried to overcome the guilt of choosing this so-called elitist pursuit of art instead of direct action. But in my own way, I think I have done my best to use art to tell the stories of social struggle and the problems of being human and more importantly, to take art back to the public.” Born in Pune in 1949, Patwardhan—a practising radiologist who quit his job to become a full-time artist only in 2005—started grappling with the Marxist ideology as a medical student way back in the early 1970s. Before moving to Mumbai in 1973 he was a contributor to the Marathi magazine Magova, which wanted to redefine Leftism by calling for social equality, more female participation in politics and active promotion of art and culture. It was a time in his life when he was spending time with activists, novelists, scientists and public intellectuals, all united by a mutual belief in Marxism’s power to change the world.

Patwardhan’s early paintings reveal an unwavering fidelity to the working class. A self-taught artist, he found a model in Fernand Léger, a French cubist best known for his depiction of the proletariat. “Initially, I thought of myself as a spokesperson for the working class,” he says. “The paintings from this period are emotional and visceral. Then, I felt I was a participant and later, as decades passed, I ultimately realised that I am actually an observer. Each position has contained a different political meaning for me.”

For the sake of labels, one can argue that Patwardhan’s art occupies the curious spot between expressionism and figuration. “For me, expressionism later became social expressionism while on the other hand, I have always been devoted to representational reality. My paintings explore subjects that are real and tangible,” says Patwardhan, who has long admired Paul Cézanne, another French master often considered the father of modern art. Cézanne’s enormous influence can be spotted in Patwardhan’s careful handling of colour and the way he builds up his paintings. Patwardhan discovered the masters of modern art for the first time in the now-defunct bookstore Manneys in Pune. After coming to Bombay, he met a bunch of artist friends with whom he could discuss ideas and painting techniques.

One of the first artists he befriended in Bombay was Gieve Patel, to whom his towering new book is dedicated. “I haven’t given him the copy, yet. I want to surprise him,” Patwardhan says, with childlike glee. Apart from friendship, Patel also plays the role of a critic in his life. “Gieve has a subtle way of conveying his opinion but if you are smart, you can understand,” says Patwardhan, who was associated with the Baroda school of painters. This phase of his life saw him hobnob with the late Bhupen Khakhar. “Bhupen was great fun to be with. He didn’t talk much about art. His remarks were oblique — but quite revealing.” Patwardhan also counts Gulam Mohammed Sheikh and Atul Dodiya as close friends.

There’s one lifelong friend and soulmate that he mentions at the end of our conversation, saving the best for last. His wife Shanta is a former dancer. She appears in his paintings once in a while, but is ever-present in his work and life. “Nothing could have been possible without her rock-like support,” he acknowledges, while Shanta stands close by absorbing the compliment. Many of Patwardhan’s pandemic paintings feature a lonely couple, engrossed in the drudgery of life’s humdrum existence. Strangely, Patwardhan had felt the same pang of isolation following his retirement from his radiology practice. “Going to the clinic every day was like a ritual for me. Different stories would unfold before one’s eyes. Suddenly, not going to work was like being cut off from the world,” he says. During the pandemic, he missed social interaction the most. “Just watching people walking by and the hustle and bustle of traffic and the city going about its business is the material from which I draw,” he says, adding, “Even if I went to my society’s gate the roads were empty. For me, the sense of loss and absence was very strong.”

Patwardhan’s art has been radically shifting in the last two decades but the pandemic has only hastened the changes further. Whereas his earlier paintings had a buzz and vibrancy the later ones recall the meditative musings of the inner world of an artist. Watching him glide from the living room to his atelier, I tell him that he reminds me of a character in a play or film. Not surprisingly, some of his recent compositions have a cinematic or theatrical feel to them. The fact remains that his dwindling interest in the urban-scape has to do with Mumbai itself not being the same city it once was. But more significantly, it’s also the case of the drying up of inspiration. The indefatigable chronicler of Mumbai finds himself at the most crucial stage of his career—late style. He admits that he’s grappling with existential dread, an emotion that gnaws at his work more and more: “There are two kinds of art statements. One where you have a conviction and you state it. Picasso says, ‘I don’t search, I find.’ The other is search — a search for meaning. Even existentialist philosophers have said that meaning and truth reside in language, not in reality. I would say that I am in a searching phase right now.”