SG Vasudev: Crafting the Covenant

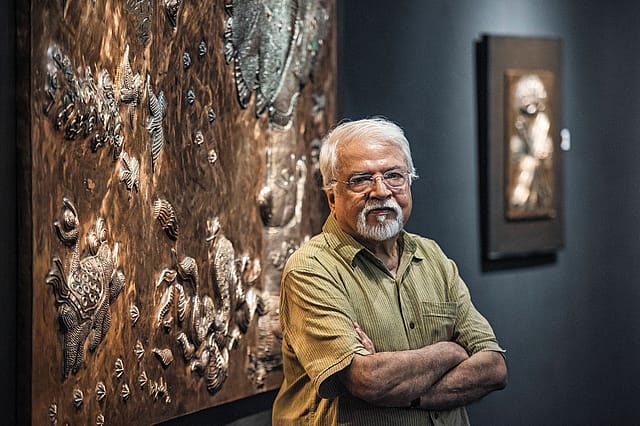

IN 1964, A YOUNG student from the Government College of Art, Madras, had a show at Jehangir Art Gallery in Mumbai. He didn't sell anything. Today, the artist SG Vasudev, is showing over 300 works at the National Gallery of Modern Art in the city. It's a retrospective quite unlike most others—spread across five floors of the gallery, and chronicling over five decades of his life as a leading contemporary modernist in India.

"Looking at some of the works from the '60s, I can hardly believe that they're my paintings. It's taking me back to those times and my thoughts… I wonder what was on my mind when I was doing these works," says Vasudev, when I meet him hours before the show opens to the public. Titled Inner Resonance—A Return to Sama, the retrospective comes to Mumbai after two iterations, in Bengaluru in September last year, and Chennai earlier this year. It has been curated by art critic and editor Sadanand Menon, who has followed the artist's work since the '60s.

Walking the circular space of the gallery, you encounter works across mediums— stunning oils on canvas, and pencil on paper. Some of the themes are also rendered on large tapestries, and copper reliefs, with entire floors dedicated to these mediums. This blurring of lines between art and craft is what Vasudev is masterful at—an ability he credits to his early days spent in Chennai.

"In college, our principal (KCS Paniker), encouraged us to work in different sections. So even though I studied painting, I learned batik and ceramics. That's how my respect for craft began," he says, adding, "Is Mahabalipuram built by artists or craftsmen? There really is a very thin line." In fact, this fusing of arts and crafts is what also fomented the formation of Cholamandal Artists Village in Chennai in 1966.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

This artists' commune, located in the then-rural hinterlands of the city, went on to establish itself as an iconic space for creative expression at a time when radical movements were on the rise, and universities across the country were in a state of turmoil. Cholamandal sowed the seeds for what we know as the Madras Art Movement today. Vasudev, who co-founded the commune, lived and worked there for over two decades.

"When we were about to finish college, Paniker asked us what we were going to do next. Many of us said we'll take up jobs. He was against this, and said he had seen many brilliant students vanish from the arts scene. He recommended that we experiment with crafts and try and make a living," recalls Vasudev, adding that he and other artists created batik works and a year later, sold most of them at an exhibition.

Vasudev's art through the decades has seen him explore various themes, all are on display at the retrospective such as—Maithuna (Act of Love), Vriksha, Tree of Life & Death and Rhapsody . Vriksha, in fact, has been a steady leitmotif in his works. We see its evolution from the '60s with elements of nature like birds and animals, to Earthscapes in the '90s, when the paintings become heavy with the weight of environmental degradation.

In 1967, at an exhibition he was having at Dharwad, Vasudev met renowned Kannada poet DR Bendre. A literary critic, who had covered Bendre's work extensively, explained his poetry to Vasudev. "One poem in particular, called Kalpa Vriksha Vrindavana in Kannada, really stayed with me. I used it to do a series of paintings. In Cholamadal too, the artist lived amidst nature. "It was next to the sea and there were lots of old tamarind trees in the compound. That influence became very strong in my work," he says.

Vasudev says that he had never heard of the Tree of Life, until a friend saw the tree element in his works at a Delhi exhibition, and pointed out what it was. He went on to read about its significance in different religions and it became a dominant theme through the years. In 1988, the artist lost his wife and fellow artist Arnawaz to cancer, and moved to Bengaluru from Cholamandal. While Vasudev had grown up in Bengaluru—he lived there until he went to art school—moving back came with its own set of challenges. "In Chennai, 99 per cent of the artists came from the same school, and had similar philosophies and politics. In Bangalore, they were from all over—Baroda, Santiniketan, Delhi—and they came with different experiences."

The late Girish Karnad had made a documentary on Arnawaz's life after her death. He noted that in her paintings, even through the period she had cancer, she didn't dwell on death or compulsion. "Whereas this could be seen in my work… of course, at the time I didn't know I was painting that. I call some of the paintings from that period Tree of Life & Death."

Karnad was a close friend, and opened up a world of associations for Vasudev. He first met him while in college—Karnad had come to Chennai from Oxford and would continue to visit Cholamandal over the years. Through him, Vasudev was introduced to prolific Kannada writers like AK Ramanujan, UR Anathamurthy and K Shivaram Karanth.

"I miss him a lot," says Vasudev of Karnad, "When Tughlaq was made in English by Alyque Padamsee, I watched it with him in Bombay. He was like family. If he was alive and in good health, he would've come for this show." Karnad inaugurated the Bengaluru retrospective last year.

This was also a time the artist dabbled in fields outside of art—he was the art director for Samskara, the film adaption of Ananthaurthy's novel, designed masks for Karnad's theatre production Hayavadana and sets for BV Karanth in Chennai. He also did drawings based on Ramanujan's poetry, and later did the cover designs for his books. "This retrospective is not just about my paintings, but also the confluence of my interests in theatre, music, dance, literature and poetry. I strongly believe that one should have a connection with other arts, and not compartmentalise, or confine themselves to just painting and sculptures."

Unlike artists who work in solitude, Vasudev thrives on collaboration. His intricate work on silk tapestries is the result of a 23-year-long association with master weaver K Subbarayulu, who he met through MF Husain at the latter's studio in Bengaluru. "Artists and craftsmen have to respect each other to have a successful collaboration. People often ask me if I have an ego problem as an artist. I don't. Only when you think, 'He can't create without me, or I can't without him,' does ego come in."

Vasudev's glinting copper relief work, on the topmost floor of the gallery, makes for a stunning departure from his portfolio of drawings and oil on canvas. In a work from the Maithuna series (1989), we see the joyous communion of man, woman and nature. The elements of nature come alive in a series of Tree of Life works from the '70s. The artist learned to work with sheet metal from Kuppuswamy, who made Tanjore plates, used in the doors of temples. "Working on copper is a very laborious process and it was important that I train somebody," he says, explaining how lacquer, copper sheets and different tools come together to make the embossed works.

A few years after he moved back to Bengaluru, Vasudev married journalist Ammu Joseph. Through her, he met other journalists, filmmakers and theatre professionals in the activism space, and this started to reflect in his work—earth scenes became shorn of their greenery. "I started thinking more deeply about environment issues after meeting Ammu. That's when Earthscapes came about. There are some exciting works from the series that I could not display here. Each one depicts people burning trees, and themselves getting destroyed in the process."

His Theatre of Life series is a compelling metaphor for masked emotions. In a red-and-black silk tapestry work, we see a man with many faces. In another oil on canvas, the man reaches outside a frame to touch masks on a tree. These works were the result of observing the lives of people in a village. "Every day, by two in the afternoon I would see them sitting in front of a TV. I did a painting with a number of heads watching an idiot box. But then I realised I shouldn't blame them. We were like that too. Even news readers are all wearing masks… they're all similar in their presentations," he says.

Music has greatly influenced his art—his interests span from Carnatic music, and Hindustani musicians like Bhimsen Joshi and Mallikarjun Mansur to jazz and contemporary artistes. Rhapsody is the coming together of many of his past themes. He titled it while thinking about the music he was listening to while painting. "In Carnatic music, there's something called Ragam Tanam Pallavi. It's a process that also applies to my painting—you start with the white pigment (Ragam), once that dries you work with the colours (Tanam), and finally there's removal of the colours to show more of the white texture (Pallavi), and a story emerges," he says.

The Madras Art Movement remained on the fringes of mainstream Indian art—according to Vasudev, the focus was on cities like Baroda, Mumbai, Delhi and Kolkata. "They never looked towards the South… nobody would bother about what you were doing in Chennai or Bangalore. Madras Art Movement was equivalent to the Progressive Artists' Group in Bombay, but it hardly got any recognition." In addition, there were no art historians in Chennai at the time to document what was happening. A select few like Josef James and Geeta Doctor took an interest and chronicled the movement.

"Things are different today, though, with the media everywhere. You can be in Mysore, like NS Harsha and make it internationally. In Cholamandal, 45 artists have donated art works to create a museum, where people can learn more about the movement." Vasudev's efforts to make art more accessible—"people don't go to museums and galleries"— have led to initiatives like Art Park, held on the first Sunday of every month in Bengaluru. It's an informal space where people, young and old, can interact with artists, view or buy their works. Ananya Drishya is a similar monthly 'Meet the artist' event. He has also created a scholarship trust in Arnawaz's name to give financial assistance to young artists.

The 78-year-old, whose foray into art began with diagrams in zoology and botany, is brimming with new ideas after this retrospective. He keeps his drawing sheet with him wherever he goes. "It's not about money or success. It's the sheer work that I enjoy doing. If I stop that, then depression hits. My classmates in college, who had picked engineering and medicine, joked about my decision to go to art school. After 50 years, they now meet me and say, 'Vasu, you made the right decision.'"

(SG Vasudev's retrospective at the National Gallery of Modern Art, Mumbai runs till August 11, 2019)