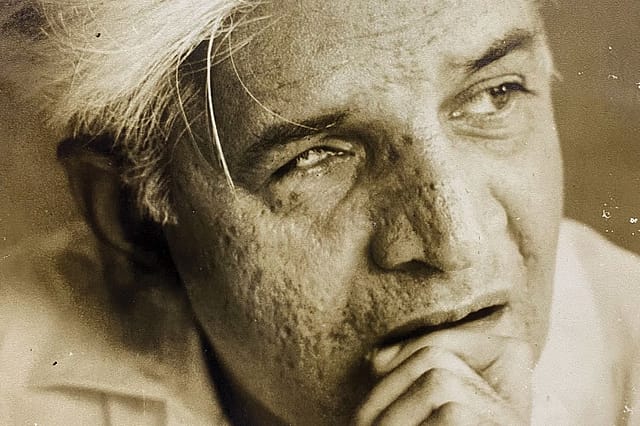

NS Bendre: The Compulsive Sketcher

BE IT BIG OR SMALL, masterpiece or disasterpiece, most paintings are built on the sinewy skeletons of a sketch. There was a time when artists would venture outdoors to draw from nature and capture figurative gestures as people went about their day. One would imagine such devotion to drawing and painting en plein air went out of fashion long ago with the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists. But seeing NS Bendre's (1910-1992) skilful studies and watercolours on display at the Emami Art gallery in Kolkata is a timely reminder of the sublime beauty of the "line". History will tell you that some of its greatest mavens, from Da Vinci to David Hockney, have reserved their utmost reverence towards drawing. Critic John Berger had summed up drawing as "discovery", while Vincent van Gogh, who was in the habit of enclosing preparatory sketches in letters addressed to his brother Theo, believed it to be the "root of everything". An early pioneer of Indian modern art, Bendre used to refer to his own sketches as "my goldmines".

In his lifetime, he did hundreds of them. Today, many are owned by his Mumbai-based son Padmanabh N Bendre (75), himself an artist, who has lent 30 drawings and 10 watercolours from his personal holdings to NS Bendre: Drawings, Sketches, Watercolours. The show highlights Bendre's affinity for the wonders of a simple pencil-and-pen sketch. A village scene, women in profile, a bustling marketplace, foliage and flowers, and traditional homes with thatched roofs — these pages from Bendre's sketchbook are aesthetically beautiful but more importantly, they are the source of his art. With rapid strokes, Bendre records his curiosities about the human figure, and the places, dwellings and the natural world we inhabit. On till December 12th, NS Bendre: Drawings, Sketches, Watercolours makes a case for Bendre as a compulsive sketcher. Most intriguing is the fact that even though his painting style continued to change and evolve down the years, in his drawings he remained strongly committed to "academic realism", staying true to the rigorous training he received under the tutelage of his first teacher, DD Deolalikar.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Richa Agarwal, CEO, Emami Art, says this is the first major Bendre show ever to be mounted in Kolkata. Spelling out his Bengali connection, she tells Open, "Mr Bendre was an artist-in-residence at Santiniketan, where he worked with veterans like Nandalal Bose and Ramkinkar Baij. He also met Atul Bose and Jamini Roy in Kolkata. So, for us, it was important to honour the meaningful ties he had with Bengal and give the audience here a chance to see his work." Reportedly, Bendre had travelled to Santiniketan by the same train as Mahatma Gandhi who was on his way to Noakhali to urge for peace following the Hindu-Muslim flare-up in 1946. During his eight-month stay in Santiniketan, Bendre used to join students and teachers from Kala Bhavana on excursions to Darbhanga, Bakhtiarpur and Bhagalpur. As he watched Bengali masters at work, he came to respect the varied styles of Bose, Baij and Benode Behari Mukherjee. Nandalal Bose was the most remarkable figure among the lot. But Bendre seems to have shared a somewhat turbulent relationship with his elder colleague. Both were products of opposite backgrounds and, what's more, differed vastly in their approach to drawing. Bose's motto of "painting from memory" instead of making them on the spot clashed with Bendre's realistic recreation of the lived experience. Speaking about his outlook towards his work, Bendre once said, "I don't create 'dream' paintings. Man is the centre of my universe along with his emotions, his love, his social intercourse, his surroundings."

Beyond its relevance to the dying art of the drawing, the other message you get from the show is that Bendre was an avid traveller and a restless soul who would take off to an unexplored destination after every exhibition. Works on display explore the full arc of the artist, starting from 1938 to the 1980s spanning his extensive travels to Kashmir, Assam, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Odisha. "He was a wanderer by nature," Richa Agarwal says. He always carried a jhola, in which he kept his pencils and paintbox and often walked for miles to get the perfect view. As a child, Padmanabh remembers accompanying his father to several sketching adventures. "In landscape painting you hardly have any time to record the changing colours of nature. So you have to be quick," he says. It was during one such trip to Uri in 1936 that Bendre met with a near-fatal accident and lost vision in his right eye. At the time, he was working as a journalist with the tourism department of the state of Jammu & Kashmir. "He was travelling in a bus which fell into a gorge. Only three people survived that crash. He was one of them. When he became conscious in the hospital the first thing he asked was, 'Where's my paintbox?' That was the passion he had for his art," Padmanabh recalls, with pride.

Narayan Shridhar Bendre was born into a Deshastha Brahmin family from Indore in 1910. The Bendres originally hailed from Pune but in 1876 a devastating famine had led them to pack up their belongings and secure a new mooring in Indore where Bendre's grandfather found a job as a clerk. Painting was the young Bendre's childhood hobby, a latent talent that was nurtured at the art school run by Deolalikar. Coming to Bombay was a turning point for Bendre. One of his earliest paintings to create a stir was entitled Street Attraction. Exhibited at the Bombay Art Society's annual show in 1935, it depicted the artist's own sister as a gypsy girl. The Bombay Art Society was especially encouraging towards a struggling Bendre, helping him break into the tightknit artistic circle of the city. The late 1930s saw him flourish as a painter, winning him plenty of commissions and patrons. "He was at the top," Padmanabh suggests. Once, there was a toss-up between him and Amrita Sher-Gil at the Bombay Art Society for its coveted annual Gold Medal. "That year, Amrita Sher-Gil won but the next year, they decided to give the prize to my father," Padmanabh says.

When the chips were down, Bendre, who was at the time living in a chawl in Dadar —Bombay's historic erstwhile mill district, started evening art classes from home. One of his most famous students was SB Palsikar who went on to preside over the Sir JJ School of Art as its dean and, in turn, played a key role in guiding and mentoring such iconic names as Akbar Padamsee, MF Husain and Tyeb Mehta. Padmanabh shares that Bendre had always been fond of Husain. Their friendship goes back to their Indore days when Bendre had encouraged Husain's father to let the newbie continue with his art education. "Dad told Husain's father that he had a lot of promise and he should give the lad a chance instead of making him work at their family shop," Padmanabh says. "Husain saab never forgot my dad's contribution to his life," adds Padmanabh, who lives in the same bungalow in suburban Mumbai which used to house Bendre's studio and house.

After India's independence, Husain was invited to join Bombay's Progressive Artists' Group (PAG), a nascent modern art movement spearheaded by FN Souza determined to break free from the influential Bengal school and the prevalent British academic style and find a new language to go with the new India. While PAG was busy gaining a foothold in Bombay's art scene, Bendre, some years senior to the group's artists, was away in Baroda. In 1950-1956 he had a teaching gig at the Faculty of Fine Arts there. Would Bendre have joined PAG were he around in Bombay? "I am not sure if he was interested or even knew about the group back then," Padmanabh speculates, adding that too much importance is attached to PAG. Meanwhile, Bendre retired as a dean from Baroda in 1966, but not before influencing successive generations of artists. What we today know loosely as the Baroda School —Shanti Dave, Gulam Mohammed Sheikh, GR Santosh and Jyoti Bhatt—have all acknowledged their debt to Bendre. The reason for his popularity among students was his teaching method, which was simple and effective. As Padmanabh puts it, "He never imposed his style on his students and believed in giving freedom. His philosophy was to let children find their own voice." Even as a teacher, Bendre emphasised the importance of sketching. "While in Baroda, he prodded his students to go to railway stations and markets to sketch, and the next morning, he would personally check their drawing books. He truly practised what he preached."

Over the course of his nearly six-decade career, Bendre flirted with many artistic styles. Both in his practice and teaching, he took cues from art history, having been one of the few artists of his era to be exposed to Western trends. He had learnt ceramics in New York and dabbled in abstraction, cubism and expressionism in different periods of his life. After his return from Baroda he started developing his own form of pointillism, which Padmanabh claims was distinct from that of French Post-Impressionist artist Georges Seurat's. Indeed, Bendre's 1970s output provides a fascinating insight into this particular phase of his creativity with "dots" — a group of young mothers cradling children, still life with flower pots, weavers slaving away at the loom, the lotus sellers, a red landscape with trees blurring into a splotched reverie. "Unlike Seurat's scientific method whereby he started by applying darker colour dots onto the canvas and then moved to lighter shades, dad's technique was different in the sense that he had a more emotional and visceral response to his subjects and he worked backwards, from light to darkness."

In the late 1960s, the itinerant artist finally decided to settle down in Bombay. He built a new house on a plot in the artist's colony in Bandra East where KK Hebbar was his neighbour. The two painters were close personal friends. "Whenever Hebbar would make a new painting he would call my father to comment on it, whereas every time dad got stuck somewhere he used to invite Mr Hebbar over. Mr Balasaheb Thackeray was also our neighbour but he was more fond of realistic paintings. We would have friendly arguments over it," Padmanabh says, recollecting family vignettes. In 1992, Bendre was still plying his trade when he passed away in this very house at the age of 81. Padmanabh, whose own collage-heavy work inclines towards American abstraction, says his father was a man of disarming modesty, never seeking fame and steering clear of politics for the most part, both in his work and life. Over time, Bendre's name has fallen off the grid even as some of his more celebrated contemporaries have cantered ahead and reached the stratosphere of 20th century art. Padmanabh echoes the same sentiment. "The contribution he has given to the Indian art world is far greater than any other artist," he adds, "Unfortunately, he didn't get the response he should have received from the government and the art community."

Perhaps, the Emami show along with another due at New Delhi's Vadehra Art Gallery will help resurrect Narayan Shridhar Bendre's reputation not just as an artist but also as a visionary pedagogue.

(NS Bendre Drawings, Sketches, Watercolours runs at Emami Art, Kolkata till December 12th, 2021)