Himmat Shah: A Lone Figure of Grandeur

FOR SOMEONE WHO translates the world through word, thus inscribing upon the self the complexity of sensual experience, confronting Himmat Shah's artistic creations is unprecedentedly destabilising. One is not reduced to silence so much as rendered speechless. Where, in other previous encounters with art, words summon themselves to form thought, in Shah's case, there occurs not blankness but a sudden recognition of a previously unacknowledged absence of vocabulary. All known verbal language is suddenly redundant. At the tip of the tongue is only the strangely familiar but until-now unfelt.

It is no wonder then that 'enigma' is the one word that seems to recur most frequently in Shah's linguistic vocabulary and that has subsequently been regurgitated in the art historical discourse surrounding his practice. "Human being is an enigma, and what he creates should also be all enigma," he said in 1994, during an interview with Hiti Mahendroo for India Magazine. The quote was repeated by art critic Gayatri Sinha in her 2007 essay, 'An Unreasoned Act of Being' while referring to his larger-than-life bronze heads that each bore 'an imprint that makes their locus a hermitic puzzle,' while their sudden monumentality embodied a presence both cranial and phallic. 'On their bodies appear marks like those of journeys in the past, like a trail etched out across the Hindukush mountains or the salt flats of Gujarat, perhaps tread by weary travellers as they traverse a death- defying trajectory. Or, perhaps they are mammoth puzzles of the human condition and its existential states that defy simple definition.'

Even over the phone, Shah preciously preserved the mystery. I imagined him on the other end, perhaps in his studio, his fingers occasionally stroking his Moses- like beard, his baritone voice masking undertones of impatience. "The artist himself is an enigma," he says, as he urges me to re-read his "philosophy" as documented on his website: 'A piece of art is created because you allow it to happen, it cannot be forced. 'I' am not creating, it is my hands that are creating, for when they have clay beneath them, 'I' am lost. Next day when I look at the creation, I wonder whether it was really I that had done it, for I had been totally lost as my hands had been shaping the clay.' Shah had referred to this state of creation, which he considers the best form of expression or abhivyakti, arising out of the deepest devotion, or sadhna. This line, too, felt familiar. I remembered remnants of it from an essay by Roobina Karode, entitled 'The Euphoria of Being,' published in a massive tome encompassing Shah's drawing oeuvre.

2026 Forecast

09 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 53

What to read and watch this year

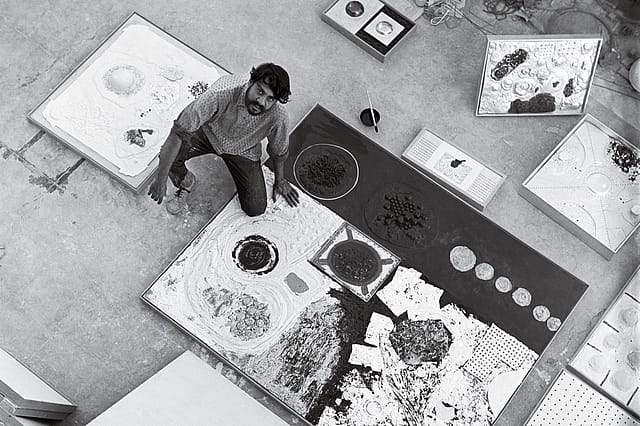

Although I had previously encountered Shah's sculptural work either in small clusters or as singular entities, it was at 'Hammer on the Square', the ongoing retrospective at Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, lovingly curated by Karode, where for the first time I was 'confronting' (or was 'confronted' by) them as a vociferous collective. I returned to the show a few days after my phone call with Shah, the rawness of emotion that had engulfed me before still very much intact. But this time around, I had in my possession, a clue from Shah himself that could help me ascertain the cause of my speechlessness, something he said almost in passing, "When I create, there is no mind. That's when creativity starts." Perhaps Shah had managed to transfer to the viewer the state of mindlessness that facilitated the making of his work, so that one could feel, second-hand, the abhivyakti that had arisen from his sadhna.

The art critic Richard Bartholomew qualified Shah's artistic predisposition as the consequence of his 'interest in the gothic underworld of the subconscious'. In his 1964 essay in Thought magazine, 'Plastic Surgery and X-ray in Recent Indian Painting', he refers to Shah's solo at Triveni gallery as a deliberate attempt to 'shock and shun sentiment'. That incandescent energy is personified in the brilliant burnt collages on display at the retrospective, inside two vitrines in the first room, all the result of what Karode refers to as one of many creative encounters that informed his sensibility. Her wall text recounts a moment in the early 60s, when, while sitting at a friend's office, Shah playfully burnt a few holes into paper with the cigarette he was smoking, which led him to invent the sensuous burnt paper collage forms, with fragile charred edges dispersing ash-dust. "At times suggestive of sculptural volume and monumental scale, these intimate compositions are among his early modernist formulations to arrive at pure form—layering, superimposing burnt paper, and juxtaposing it with pieces of coloured paper." These were first exhibited at the sole exhibition by the seminal, though short-lived, Group 1890, co-founded by Shah with J Swaminathan, at the Lalit Kala Akademi, New Delhi, in 1963, and inaugurated by Jawaharlal Nehru.

"No one was ready to exhibit the burnt paper collages," Shah explains over the phone. "I thought, let me make a head with lines." This over-simplistic rationale betrayed the intriguing genesis of his terracotta and bronze heads, which he relayed to me in bits and pieces as he spoke of the "gaon ka talaab" he frequented as a young boy growing up in Lothal, who, afraid of water, would sit by the edge and watch his friends swim, their heads first disappearing then reemerging from beneath the surface. '… The head seen above water, without the body was hypnotic in its elusive presence,' Karode writes. Shah also spoke of the keede makode he used to see crawling over the dried up lakebeds. It was the scrawl they left behind that fascinated him as they dug through the caked earth to enter its ensuing fertile entrails. This remembered pattern was what he replicated across the surface of numerous terracotta works, endowing them with a cartographic lexicon.

THE ROOM IN which these heads are placed on tables in groups of three or as solitary structures seems to replicate that sight of heads having reemerged, of a consciousness having been born; baptismal newness. Look at any head determinedly and Krishen Khanna's prophecy comes to mind: "If you stay with them long enough you might be switching roles. You the observer can become the observed in their mute presence." Among them, a gold leaf embossed plaster-of-Paris head stands out as if to channel a state of enlightened being. The idea of the object as an archeological artefact testifying to a civilisational past must have been ingrained in Shah's artistic vision from childhood itself, having grown up on a site under which lay the ruins of Harappa. Lands belonging to many members of Shah's extended family were appropriated by the Government for the purpose of excavation. 'You grew up amongst them and these powerful images have persisted in your memory and now appear in the guise of your sculpture,' Krishen Khanna said to Shah in a cursively handwritten letter dated March 2007. 'They are not fragile and emit an aura to keep evil at bay.'

As a child, Shah ran away from home and school, allegedly to escape from a life of conformity and routine. He wandered through the wild landscapes of Gujarat and Rajasthan, walking tilled fields and the desert, climbing hills, living in desolate caves and sleeping under the vastness of the sky. When he did venture into art school, he sought the tutelage of NS Bendre at MS University, Baroda, and eventually set up base for many years at Garhi village, before buying himself a modest accommodation in Jaipur, where he now resides. 'Self-styled, Himmat defied categories such as a painter or sculptor and dismissed the existing hierarchy of art forms that assigned drawing to perform primarily a preliminary function,' wrote Karode, who successfully adopted this egalitarian position as the premise for her curatorial approach. Resisting chronological methodology, she has opted instead for engendering a display that more aptly depicts the simultaneity of Shah's artistic proclivity with different media. The unspoken narrative that binds the 350-plus works together is affected through the sense of continuity produced by the showcasing of Shah's drawings as a running thread in every room, until it hits a climactic peak. Each drawing effectively reveals Shah's facility with the notion of the line as an intuitive gesture with no clear destination, with form as feeling. "There are so many different kinds of lines," he explains, "the crack on the wall, the crack on an old pot… but in reality, there is no line in nature." According to Karode, his drawings bring to fore certain self- invented techniques that he employed, "for instance, there are his drawings that use a single unbroken line to articulate a complex image in its essential form. Parallel to this are his drawings that employ a looping methodology, following the informal movement of the pen, making loops that embroider a dense tracery. Shah also invented the constructive stroke, drawing straight lines, abstracting the idea in a formal flat geometry with brick-like blocks ordering the space to create visual music or a rhythmic composition. The languid scrawl of his automatic drawings later evolves into a highly gestural calligraphic script emphasising the inscrutable beauty of a moving hand."

'Hammer on the Square' is the sum total of all of Shah's predilections and experimentation with form. It even has the reliefs of his monumental murals in brick, cement and concrete, made in 1967 at St Xavier's School, Ahmedabad, his silver paintings, and most recent bronze heads. At least 215 of the works on display are part of the KNMA's permanent collection, no small achievement for the country's only privately run museum. It was fitting that Karode curated this show, given her long-term engagement with Shah's practice, which allows her the privilege of a vocabulary with which to articulate the inner workings of his mind.

What she has offered us as viewers is the opportunity to gleam the primacy of Shah's creation. In an era where most contemporary art is so beholden to the deluge of textual explanations that attempt to demystify the doggedly conceptual, Shah's work presents a refreshing respite. The earthiness of his material is consciously laid bare, as is his revelation in the unbridled sensuality of the lyric form. "Language is useless, we can't express in language, therefore make art," he says over the phone. "The writer will only create a wall between the artist and you," he adds, leaving me to grapple with my linguistic predicament.

('Hammer on the Square' is on view at the KNMA, Delhi , till 30 June)