Flubbergast Yourself

Meet Flubber. He wears baby powder to work, holds up traffic after he is done for the day, and claims he was not born this way. The story of how a copywriter with an MBA turned into a clown

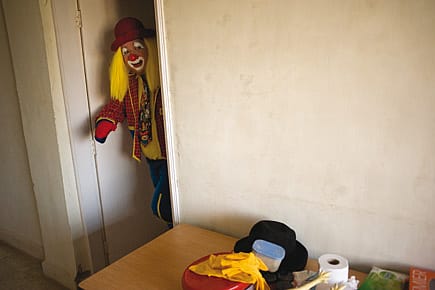

Mirth in Mumbai can erupt in strange places. But the sight of a gaggle of kids seized with fits of uncontrollable laughter in the middle of a Jogeshwari street would still make you stop to see what's going on. There was no clear line of sight to the centre of the crowd, but brilliant golden yellow flecks kept peeping out amidst the dull greys and browns that clad the children. Closer inspection revealed a large, lovable clown with yellow hair, a tomato nose and joie de vivre of someone who has just had a flower squirt someone with water.

Street kids love the clown, and the clown loves street kids. In fact, they're pretty much part of Martin D'Souza's after-work routine now. "I refuse to change into my regular clothes when driving back home," he says, pleased to be the bright spark in what might be dull lives otherwise, "It is amazing to see the kind of reactions I get. Beggar children come and stand by my window and smile at me. They never beg, they simply come and look." It makes his day.

Martin holds the distinction of being one of India's few professional clowns—and only Indian member of the UK-based World Clown Association. An MBA, he runs an event management company, Light House Entertainment, in Jogeshwari, but spends most of his time thinking up ways and doing what it takes to tickle people across the country.

Rule Americana

16 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 54

Living with Trump's Imperium

Martin has been clowning for 25 years, and has made people bare enough teeth to more than justify quitting his one-time job as a copywriter. "I felt the need to do something different, something creative," he recalls, "I did some research on juggling, magic, etcetera, and then realised that a clown could do all that and more." A jack-of-all-trades—a juggler, mime artist, balloon sculptor and magician all rolled into one—was what he longed to be, with never a separation between one or the other.

NO ATOMISED ART THIS

The first time he tried on clown makeup, though, he set off a meltdown. Unaware of the special cosmetics that professional clowns use, Martin used water colours—only for the clammy humidity of Mumbai to turn him into something even the cat would not bring in.

Determined to get it right, he wrote to clowns in the West for advice. If they had any to convey, it must have been in mime—he got no word of response. But in 2001, the University of Wisconsin mailed him information on a clown school. Martin signed up. He learnt that there is something called a balloonologist: "Someone who transforms limp balloons into lovable animal characters." He learnt new skills too, but higher education anywhere is about higher specialisation, so he also learnt that "there are broadly three kinds of clowns, and hence three styles of makeup".

There is the classic whiteface clown, stylish and irreverent, with a few variations—one could be a neat whiteface with little colour and a white costume, ora grotesque whiteface, first made famous by the legendary Bozo with his trademark blue-and-red attire and oversized hair, and now mostly spotted in the form of Ronald McDonald, the cheery fella who wants the world to 'Mac love, not war' by gorging itself on burgers and cola.

The second type is the naughty and bubbly Auguste (pronounced Agoost), who adorns himself with colour. He dresses in an ill-fitting costume and his features tend to be exaggerated, with his mouth and eyes typically outlined in white. "The difference between the grotesque whiteface and Auguste," says Martin, "is that the former is more sophisticated, while the latter is more clumsy, always making a fool of himself." And the third type of clown is the hobo or tramp, brought to life by the cinema legend Charlie Chaplin. "He always gives the impression of being sad, depressed and down on luck."

For Martin, the choice was clear. Not for him the depressed look or sophisticated style. What held his fascination was the ever-vibrant and mischievous Auguste. And so it was that ten years ago, Martin contorted himself roundly to give his audience Flubber the Clown.

Even a name as gelatinous as that offers no escape from some of the hard rules of life, though. His MBA, as his two chartered account brothers advised him, needed to be put to use. "They encouraged this eccentricity in me as a hobby, but they wanted me to have a primary source of income," he says. That's how his event/party planning company came about. But clowning was his passion.

CHICKEN AND EGG

The first few performances nearly turned Flubber the Clown into Flubber the Pulp. Clowns, in popular perception, were meant to be battered. So people would joyously pull his ears, stomp on his feet and use him as a punching bag. "Not to mention the condescending looks I would get when I told people that this is what I did for a living," says Martin, "They would think that I was a complete idiot." And if he did as much as suggest someone else took up clowning, they'd be offended. To do well, he first needed a market, but a market would come about only once clowns caught on.

The crisis, however, has been cracked. The past two years have seen a change. Clowns, in popular perception, are meant to be batty. And lovably so. Now people have no inhibitions walking up to him to ask for a big hug. "I am 6 ft tall with a lively animated voice," he exults, "My huge huggable personality appeals to both kids and adults." Now it's his heart that turns gooey, not his makeup. Why, he even has it on while eating lunch. It's his second skin, as much part of his personality as anything underneath. "All one needs to do is set it with a bit of baby powder, and then it will stay on even in humid conditions," says Martin.

Like an overgrown baby, Flubber is free of the behavioural bounds of adulthood. But the thrill is to have others drop their guard and join the fun. At Mumbai International Airport recently, he decided to do some impromptu clowning for a group of frustrated passengers of a badly delayed flight to Dubai. "In a matter of minutes, these tired travellers were giggling and clapping like little kids. There were women in burkha whose reactions I could only gauge by the sudden glint in their eyes. Elderly men, who were earlier watching from afar, came closer to be part of the show," laughs Martin, "Everyone was like 'Aap pehle kyun nahi aaye (Why didn't you come in earlier)?'"

The effect is even more dramatic on those who need cheering up the most: the distressed. At a recent Clown Festival, he took caring clowns from around the world to Mumbai's KEM Hospital, where they performed for children all day long. "The children there surprised everyone. Not one was afraid to make a fool of himself. They were all aching to wear the clown nose. It was so good to see them strip free of all inhibitions."

Of regular customers, Martin charges Rs 25,000 per show. This is about ten times what ordinary clowns charge, but Martin says he has invested good money in his act, too. "I have proper big floppy clown shoes, the right kind of props, a unicycle, juggling balls, magic kit, and pocket tricks like the rubber chicken."

Ah, the rubber chicken. It leaves kids and adults alike clucking in delight, and that's the idea, even if it means letting the odd egg come first. If clowning can be caring, Martin says, it can also be educational—about healthy eating, say.

In the West, clowning is an art that is still being perfected. "I have also come across clown ministers who teach about religion through their shows." Anyone can be a clown, he adds. "A person can be an introvert and still be a good clown. You just need to be intrinsically happy. That's the fundamental difference between a joker and a clown. A joker just tries to make you laugh, but a clown makes you happy."