A Tough Compromiser

With the passing away of Günter Grass, Europe has lost one of its prominent voices in literature, arts and public opinion. Grass was always a writer and thinker of many creeds—the best of which often came in the literary world as dark fables, ironic representations and above all, as the dense and tangled jungle of psychological realism. With his extravagant sense of humour and irony, the worlds he traversed were numerous; as he said in one of his interviews, "Europe itself posed its question of the Other" always. You can live here as a Catholic, as a Protestant, as a Jew, as a nomad; but the veritable questions that make you the 'other' will be more crucial than any other identity. In other words, Europe itself was rediscovering its 'other' over many centuries. But the last century was its apotheosis—the two World Wars that shook the world, religious fanaticism and fundamentalism in their rapid surge, and provincialism gaining momentum over nationalism. Grass had to voice his concern amidst this cornucopia of divisions; which, in other words for him, were the images of a torn continent.

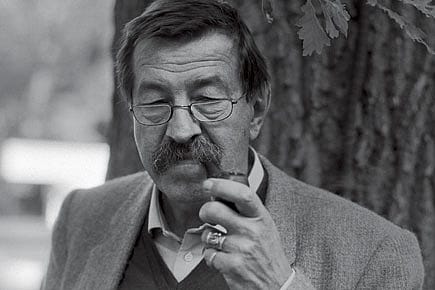

It is with the publication of The Tin Drum, the first novel in the Danzig trilogy, that Grass stamped his career on the literary map of Europe. The reception the text received was beyond comparison, a phenomenal breakthrough in the history of the European novel, perhaps more than what the powerful existential writers from France preceding Grass received. The text also opened up new channels of narration, of which one in contemporary times claims the mode of 'magical realism'. However, the Danzig trilogy was received with much enthusiasm by readers all over the globe as a testimony of the 'guilt consciousness' of the German mind. Of course, Grass was the product of this strange guilt consciousness. He wanted to reveal the psychosis of fascism and the troubling sense of an insider. But he never wanted to always remain an insider. The travels he undertook after the 60s to other parts of the world, including Israel, Palestine, the Middle East and India, reveal the fact that he wanted to explore the other side of Europe. Wherever he travelled, he carried the magical qualities of Oskar Matzerath—the much acclaimed character in The Tin Drum. With loosely fitted thick glasses on his nose and a pipe on his lips, he delved deep into the issues of the nations he went to. He painted, sculpted, sang at parties with the people he made friends with, and tried to forget the terrible past of the Holocaust and the parochial politics that followed.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The political stance of Grass was always problematic. His late confession in 2006 that he was a member of the Waffen- SS during World War II shook the world. A few at least were not shaken by his remarks—those who knew his writings well and had seen the film adaptation of the text by Volker Schlondörff. The film subtly outlines the autobiographical Grass. However, the revelation of Grass' Nazi past was forgiven by his readers as his writings had too many things to offer. While the great German intelligentsia, including Martin Heidegger, had a very clear Nazi past, there is nothing to brag about in Grass' own past. But later, Grass played his cards strategically. He was always a man of verve in the sense that he hated Republicanism and German unity in the 90s, and moreover, distrusted the coalition governments coming up in the world. His poem in 2012 criticising Israel's tirades against Iran was condemned by several poets and activists. Political analysts thought that Grass was siding with Iran's nuclear strategies and was trying to appease the Middle East by pitting one country against the other. In fact, Grass was in opposition to Israel's political stance against Iran; not against Israelis per se. Unlike thinkers and public intellectuals like Edward Said, Nawal el Saadawi and Saba Mahmood, Grass never voiced his concern over the innumerable issues within the Arab world. A staunch critic of American imperialism, he found his safe haven in the thinking of the neo-liberal and global world—another comfortable stand a writer can resort to. Women were not allowed into his thinking schemata, nor were they given adequate representation in politics.

Grass' relationship with India is both fascinating and intriguing. It is difficult to comment on which India he was trying to grapple with. During his stay in Calcutta in 1986– 87, he was terribly disturbed by the communist hegemony and sad working conditions. His sketchbook of Calcutta reveals not an oriental gaze, but a mediating sensual approach to the problems of poverty, unemployment and subaltern life. He loved Indian myths and folklores, but unlike a Roberto Calasso, never wanted to bring them into his writing, nor demystify them. When he was at Maharaja's College in Kerala in the early 70s, a group of professors interviewed him. When asked whether Nietzsche was the German philosopher he liked most, his reply was a big 'No' and he said that it was Schopenhauer who influenced him most. Similarly, he claimed that he didn't know Jean Genet, the towering writer from France and an indispensable figure of queer and prison writing.

But Grass predicted the recognition of Joseph Brodsky, who at that point of time was not much known in India but later became world famous after his Nobel prize. Grass' relationship with India never prompted him to write a major text on the country. Unlike a few other German scholars who saw India as an abode of their thought and Indology a highly relevant subject, Grass had his own notion about what India was and where India could be in a globalised world.

Above all, Grass was a sceptic. His pungent criticism was aimed at the intellectual middle-class and the writers' bloc who write for recognition. He was not bothered about any recognition, and the much-awaited Nobel prize was given to him only in 1999. In a sharp political satire like The Rat, he makes the she-rat narrate the history of the animal race and jolt at Albert Camus, whose The Plague is a celebrated text of the human predicament. In his famous play Coriolanus, he makes the generals stumble at the stupidities and vagaries of the modern world order. In another novel, The Crab Walk, he problematises the memory of victims and perpetrators of violence. The incident of a shipwreck where an army is situated and the deep obfuscation of memory after that are rendered as the unavoidable chasms of conquest. The governors and sergeants that appear all over his texts are victims of ridicule.

He doubted the world order with any fixity. Does it imply that he had in him some deep seated anxiety of a neo-Nazi uprising? One would even wonder how he kept a vigil of the 'other cultures' in Europe, particularly in Germany.

Always a tough compromiser, both in his politics and in writing, the 'guilt consciousness' Grass inherited had many followers. German writers like WG Sebald, Christa Wolf and Peter Handke owe a lot to Grass in terms of their thematic and narrative strategies. The post- Holocaust question of archiving memory is another aspect that emerges in the speeches Grass delivered at Turin over the past few years.

Grass disliked the social media for the viral spreading of messages. His comment, "Facebook is fraud. One who has 5,000 friends has no friend at all," is a testimony to that dislike. Somewhere, he kept the accuracy and precision of reporting and detailing incidents. He believed that the world can never be the same forever; but he also sensed the pulse of the ground shaking as regions and provinces began to tear themselves up.

How Grass is remembered would be judged on his involvement in world politics, where one needs to separate his private from the public. But Grass constantly tried to tell us that his private is very much the political. It is here that his entire oeuvre of writings will be judged and his public appearances and statements will be critiqued.

(Krishnan Unni P is an associate professor of English at Deshbandhu College, University of Delhi)