An Unequal Music

Between the solitude of the Indian raga and the social notes of Western classical

Carlo Pizzati

Carlo Pizzati

Carlo Pizzati

Carlo Pizzati

|

21 Jul, 2023

|

21 Jul, 2023

/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Unequalmusic1.jpg)

Sir András Schiff performs at the Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza at the concert in honour of Andrea Palladio (Photo Courtesy: Colorfoto Vicenza)

THE HANDS OF THE conductor flutter like two white doves around a pristine nest—the greying head of star conductor Sir András Schiff. An ecstatic tension seems to infuse electricity into the still air of the Teatro Olimpico in the Northern Italian city of Vicenza, during this fourteenth ‘Tribute to architect Andrea Palladio’.

Behind the orchestra, gathering some of the world’s best musicians summoned by the Hungarian genius, I imagine the invisible musical volutes of Bach, Brahms, Mendelssohn, and Schumann vanishing among the perspectives of the three Theban roads on the stage.

From my front row seat, I turn around to study the audience when the concert reaches its peak. I observe many smiles enraptured by joy, gazes absorbed by the masterful technique and passion of the performance. No one is bored, everyone understands, with their senses or their mind, that they are facing a memorable evening, overwhelmed by a cascade of applauses begging the talents to return to the stage, to repeat the magic, encore!

Schiff’s perfect music machine resumes with a Lieder. I let myself be carried away by the melody, imagining castles of notes built in the air with the composition. I’ve just returned to Italy after many months in India and I cannot avoid a continuous comparison between the music born where I now live and these classical compositions that are so familiar to me, since I listened to them when I was growing up here in Italy.

The first night of my life that I slept in India, in 2008, it was precisely a classical music piece I was listening to in a tiny rented room in Mysore that created the soundtrack of an understandable cultural shock on which I often reflect.

“Tuba mirum spargens sonum / per sepulcra regionum / coget omnes ante thronum.” The solemn ‘Tuba Mirum’ of Mozart’s Requiem says that the trumpet, diffusing a wondrous sound over the sepulchres of the world, gathers everyone around the divine throne to witness the universal judgment.

It is a representative text, a majestic trombone solo describing the end of days, the apocalypse when “everything that is hidden will appear and nothing will remain unpunished.”

The narrator’s song of the ‘Tuba Mirum’ wonders: “What can I, wretched man, say? Who will I call to defend me, when even the just cannot be safe?” On that first Indian night, I did not register the meaning of the words, and yet it was as if an invisible hand made of notes burrowed into my chest, into my stomach to slowly tear my organs out, up to my throat, and re-emerged in the shape of tears.

In those deep notes, in that baritone tale supported by the sounds of that trombone, those cellos/basses and voices, I felt all the depth and authority of European culture condensed, which seemed to slowly evaporate into the darkness of the Mysore night.

It was as if I felt that I would never see anyone again of all my friends, relatives, and dear ones that I had left behind in the West as I ventured into my first journey to India, the country I would end up moving to. It felt like a funereal hymsn to the death of the past, as I was facing a truly indecipherable future in a most alien land for me, that night. A day of judgment, as the words of the ‘Tuba Mirum’ say. As if the perspective on everything that represented my roots, namely Europe and America, the infamous West, would change forever. The important thing, here, is that it was precisely this classical piece, so full of narrative, that operated as a symbol of a rational and expressive identity, my European identity.

A Day of Judgment, as the words of the ‘Tuba Mirum’ say. As if the perspective on the infamous West would change forever. The important thing, here, is that it was precisely this classical piece, so full of narrative, that operated as a symbol of a rational and expressive identity, my European identity

This is what I was thinking about at that concert in Vicenza. The notes extracted from the air by the white hands of Sir András Schiff, while I observed the virtuosities of his orchestra, manifesting themselves as a code that perfectly represents the culture that expresses them, like clock gears that oscillate with precision at the right moment.

Science, technology, the perfect execution of viola, violins, cello, trombone, French horn, classical flute and clarinet, a challenge between two pianos: these are all gears of a mentality that finds its fulcrum in passionate and eager organisation, in the ability to build a device, in this case a musical one, composed of well-calibrated and dosed notes, played artfully and in unison by almost always impeccable performers—an absolute system that reflects the rationality, engineering, and mechanics on which the West built a self-proclaimed superiority, imposed and financed by colonialism, and of which it is still so proud.

Literally, it keeps banging on about it.

Classical music as an algorithm; therefore, as a software program. I know it’s a mistake of our technological era to try to explain everything through the gears of the instrument that has transformed our times the most—the computer. Humanity is much more than one of the structures it has created. Using transistors as mirrors of the complexities of our society is a form of laziness feeding on and at the same time nourishing the limits of the contemporary, in a vicious cycle. It was instead good old Western classical music, that evening at the Olimpico in Vicenza, that represented so well everything that Europeans have been and still are.

Like many European bourgeois of the last century, I grew up with the idea that the study of classical music represents the common denominator of what in the West is considered high culture. It’s a social conquest, the proof you earned enough free time to study something ephemeral yet central to the European identity.

My paternal grandmother’s family were merchants who emigrated to Italy from Vienna, the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the time. To them, the study of oil painting and piano playing represented an undeniable emancipation, an aspiration towards a more respectable role in a small ancient world. A social step on the steep ladder of recognition.

My paternal grandmother Marì, after studying eleven years at a music conservatory, would while away her time painting acrylic oil landscapes of our mountains and valleys. She became my piano teacher, pulling hard on my elementary school fingers with what I perceived at the time as a form of the unconscious mild sadism of a Prussian upbringing. Clamping them with painful fervour, she said that fingers should strike piano keys come piccoli martelli, “like little hammers”. Just like the hammers I discovered when I opened the piano lid.

This is Western classical music to me: the musician must become the instrument in order to play it. In a very Christian way, suffering is unavoidable and almost welcomed, in the process. It opens the path to musical knowledge. Indeed, inside the piano I found the mechanical gears of a sublime music the mastery of which is representative of a social role. But in order to access it, one must suffer, hardening one’s humanly organic softness, breaking one’s lips on the mouthpiece of a trumpet, biting the reed of a clarinet, or growing calluses on the strings of a violin, cello or guitar. To improve, one must suffer; another intrinsically Western value implicit in its music.

For Helen Schlegel in Howards End, Beethoven brings back ‘the gusts of splendour, heroism, youth, and magnificence of life and death, and, among great roars of superhuman joy, brings the Fifth Symphony to its conclusion.’ No wonder it is called the ‘Symphony of Fate’

The role of classical music as a tool for social emancipation—as recounted by the brilliant Finding the Raga: An Improvisation on Indian Music by Amit Chaudhuri—was also pondered by the South African Nobel laureate in literature, JM Coetzee, remembering how he was entranced by listening for the first time, at 15, to Bach’s preludes and fugues from the collection The Well-Tempered Clavier: “I wondered if that music was speaking to me through the centuries or if instead I was symbolically choosing European high culture, seeking to master the codes of that culture as a road that would emancipate me from my social class in South Africa, stuck in a cul-de-sac of history.” In other words, music as refinement of the soul, because it teaches how to scrutinise its movements.

Despite the ambitions of the European bourgeoisie of the 1980s, the humus of my upbringing now shattered by a democratisation of taste that leads currently to the robotisation of the human voice represented by the abuse of autotune in the popular hits, classical music still epitomises the backbone of a Western identity precisely thanks to its intensely representative aspect.

This is well described by the character of Helen Schlegel in EM Forster’s Howards End, as she listens to Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony and sees “heroes and shipwrecks in the musical deluge.” For her, the German composer brings back “the gusts of splendour, heroism, youth, and magnificence of life and death, and, among great roars of superhuman joy, brings the Fifth Symphony to its conclusion.” It is no wonder that it is called the “Symphony of Fate”, Schicksals-Sinfonie.

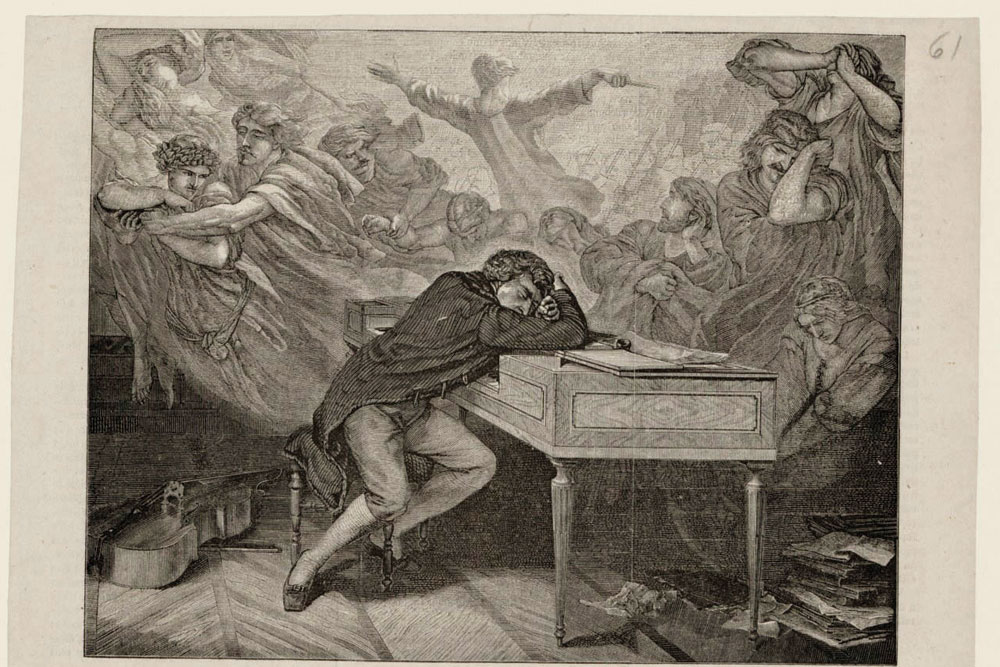

This was also Beethoven’s fate, to become deaf while composing the Fifth, creating music whose “luminous rays shoot into the deep night of this region, and we realise the gigantic shadows that sway back and forth, approaching…” as ETA Hoffmann wrote in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung after hearing it for the first time.

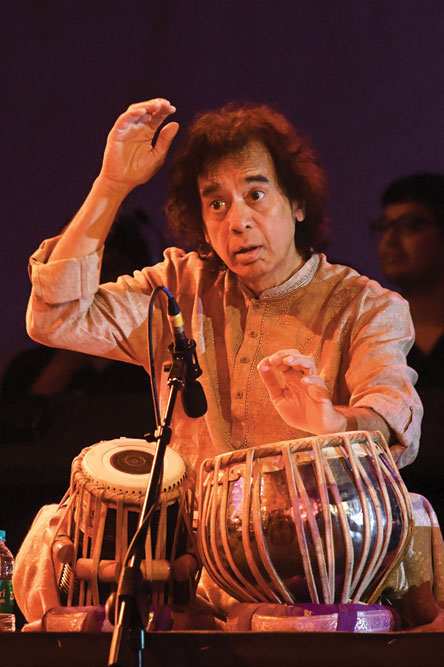

THEREFORE, ADMIRING the epic tale of what the West is, on that memorable evening at the Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza, I thought, in juxtaposition, about how it compares to Indian music. I remembered with fondness the Carnatic music concerts in the December festivals in Chennai, the Hindustani dhrupad of the Gundecha Brothers that I’ve heard perform in India but also in Sydney, in Amsterdam, or at a private concert in Bassano del Grappa, near Vicenza. Or the pyrotechnic concerts of Zakir Hussain at The Music Academy, or TM Krishna’s voice at Spaces on Elliot Beach, or the energising sound of the revered Vikku Vinayakram, with his worthy son V Selvaganesh and his talented grandson Swaminathan Selvaganesh. And I reflected on the fact that these interpretations seemed, instead, often based on the importance of improvisation and inspiration, like jazz or blues, and to the time of day they were performed. This music seems more integrated naturally and harmoniously not only with the performer and interpreter’s state of mind, mood and emotions, but with the reality around the performance, including the time of day.

Indian music and the singing of a raga, whose memory overlapped in my mind as if in a bizarre fusion experiment with the perfectly executed Schumann in Vicenza, seemed to me more inspired by the idealisation of a lament or a cry of joy, love, or spontaneous devotion to the divine: they do not necessarily build up an emotion in a narrative way, but they use that natural lament to bring the listener to an immediately abstract and mystical plane.

The only narrative, even though it would be more correct to speak of direction, is that of a union with the Whole. This is condensed in a poignant lesson from the touching and profound The Disciple, a must-watch feature film by the young Indian talent Chaitanya Tamhane, in which a raga teacher explains that “there is a reason why Indian classical music is considered an eternal quest. Through the raga, we discover the path to the divine.”

These interpretations seemed based on the importance of improvisation and inspiration, like Jazz or Blues, and to the time of day they were performed. Indian music seems more integrated harmoniously with the performer and interpreter’s state of mind, mood and emotions

In a certain sense, Indian classical music arises more naturally through the wailing voice but quickly reaches a spiritual abstraction. Indian classical music appears to be more connected to the human body and its impulses, culminating in a transcendental elevation. It appears, to a talentless and embarrassing clarinet, flute and piano player such as myself, more integrated with our humanity.

Instead, Western classical music seems to be born in a more abstract and mechanical way, as the pinnacle of creativity that aims to rise above human nature, a sonic representation of an idea that transforms into emotion, exaltation, a boiling of feelings, an orgy of Sturm und Drang. Pure creative illusion, in Vedic terms.

Perhaps this happens precisely because Western classical music expresses itself as an abstract mechanism that domesticates the body at the orders of the written notes, melodies, and harmonies encoded by the software of the score from which it is forbidden to deviate: it is therefore a more clearly mathematical, less sensual impulse, a soundtrack of rationality. It is too controlled.

In Finding the Raga, writer and musician Amit Chaudhuri expertly reflects on the excessive control of Western music, recalling how some Indians relate to traditional Western classical music. For example, his mother, upon hearing classical music for the first time in London in the 1950s, felt only profound sadness. Whereas Rabindranath Tagore in his memoir Jiban Smriti (My Reminiscences) tells of two years spent in London, between 1878 and 1880, during which the voice of a soprano reminded him of a neighing horse, while the piano seemed to him an inferior instrument because it was not capable of performing the glissando, which the violin could do, making it better, in Indian terms, because it is more flexible for personalising the sound. It was a criticism infused with anti-colonial rage but reflecting a spontaneous reaction to the ‘mechanical’ nature of classical music that Europeans find difficult to grasp, since we grew up inside it.

It is precisely this openly representative nature of Western classical music that makes it perfect for cinema and, subsequently, for the degrading abuse in cartoons and advertisements that have transformed the sublime sounds of Beethoven, Mozart, and Vivaldi into kitsch, through excessive and out-of-context reproduction of high compositions that have sunk into the depths of representation.

Sound and narrative. Happiness and sadness skilfully reproduced with music that encapsulates the trauma of modernity for the Western mind, lost in the investigation of the crisis of civilisation and of the self.

This was also the opinion of Satyajit Ray, who lamented the “lack of a tradition of dramatic narrative in Indian music”, then elaborating that “Beethoven’s symphonies speak of universal brotherhood, man’s struggle against fate or the passionate outpourings of a soul in pain. The sonata, with its masculine and feminine subjects and their intertwined progressions through dramatic key changes, reaches a climax… but a raga is a raga.”

Ray referred to an elusive otherness of Indian music, an intrinsic and almost indescribable immediate mysticism, from the very first notes, which investigates spirituality, too often confused, even by generations of Westernised Indians, with religion.

Tagore reflects on the search for harmony in Western classical music, which he sees as a music of the day, opposed to the nocturnal world of Indian music: tender, serious, pure ragini, the melody of the raga. Both move us, yet they are opposed

To understand this depth, one must reread Tagore who, in a letter from 1894, recounts a night spent on a floating house sailing on the Shilaidaha river, listening to the sound of water filling the silence of darkness. In this epistle, the Bengali poet encapsulates the dichotomy that revealed itself to me, upon returning from India, listening to the mastery of Sir András Schiff at the Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza.

Tagore, in fact, reflects on the search for harmony in Western classical music, which he sees as a music of the day, opposed to the nocturnal world of Indian music: tender, serious, pure rāgini, the melody of the raga. Both move us, yet they are opposed. Like the monotheistic religions’ idea of conquering Paradise through good deeds is opposed to Moksha, the liberation from Samsara, the cycle of reincarnations and the play between desire and suffering.

“Our music is a song of personal solitude, while that of Europe sings of social accompaniment. Our music takes the listener beyond the limits of the daily vicissitudes of humanity to that lonely land of renunciation that lies at the root of the entire universe, while European music dances in various ways around the eternal ebb and flow of human joys and sorrows.”

/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Cover-War-Shock-1.jpg)

More Columns

The secret that Pak military spokesperson wants to hide: Dad’s loyalty for Bin Laden Open

India hammers Pak air bases at Rafiqui, Murid, Chaklala, and Rahim Yar Khan in a show of unflinching force Open

How India (re)built its defence preparedness and war readiness V Shoba