Riding the Surge

The Omicron variant may be mild but India is preparing for its healthcare system to be overwhelmed by the numbers

Lhendup G Bhutia

Lhendup G Bhutia

Lhendup G Bhutia

Lhendup G Bhutia

|

14 Jan, 2022

|

14 Jan, 2022

/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Covid1.jpg)

(Illustration: Saurabh Singh)

AT THE START of December last year, India stood at an anxious juncture. A newly discovered Covid-19 variant, Omicron, was ratcheting up infections at an unprecedented rate in South Africa and moving rapidly through the world. It was a matter of time before it would land here, too, if it hadn’t already. Only a few months had passed since the crisis of the second wave had ebbed. Were we going back to the mercy of the virus again, the endless nights of screeching ambulance sirens, and cremations that went on late into the night? Or would the natural immunity granted through such a devastating experience and the ongoing vaccination campaign see us through, relatively unharmed?

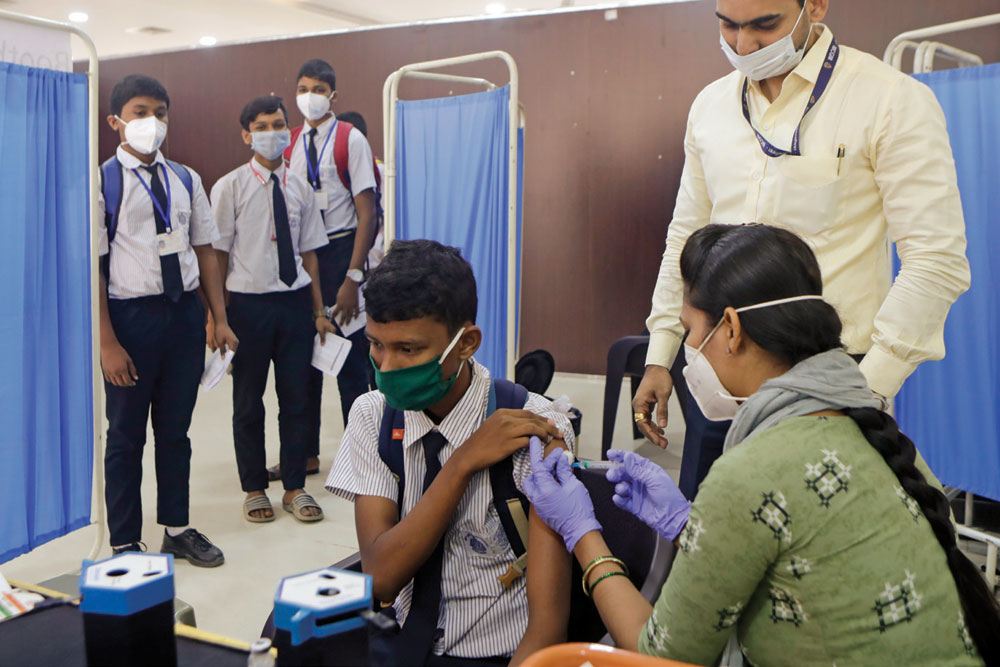

Not all the answers are clear yet. But some things are beginning to be evident. A little over a month since the first cases of Omicron were reported in India in two unrelated individuals—a South African national and a doctor in Bengaluru—there has been an unprecedented surge in an extremely short period that has flabbergasted public health officials and experts. And unlike the second wave, where the rise occurred over a period of time, growing first in some large cities and states before other areas started to show spikes, this rise has been fairly sharp in a number of places. But mercifully, it has not led to a comparable rise in hospitalisation and deaths so far. There are however very real threats that this variant, although putting a smaller fraction of its infections into hospitals, through its sheer volume of cases, may still overwhelm healthcare facilities.

In the second half of December last year, Manindra Agrawal, professor of mathematics and computer science at IIT Kanpur, who has been predicting the severity of various Covid-19 waves using a computer model (Sutra) and has often been consulted by government bodies, began working on the likely scenario of an Omicron-induced third wave in India. The model was developed by Agrawal and Mathukumalli Vidyasagar from IIT Hyderabad. Running the model on data observed during South Africa’s experience with Omicron showed a peak in India of around 1.8 lakh new daily cases by early March.

It made sense to use data from South Africa. “The two countries are pretty close when it comes to the age profile and the level of natural immunity already in the system,” Agrawal says. If anything, given India’s larger vaccine coverage, the country stood a better chance.

In the last few weeks, it has become evident that India is following a much steeper rate of increase in cases than the one witnessed by South Africa. According to even conservative estimates, the country is set to breach the earlier daily reported high of 4.4 lakh cases last year. Just by January 11th, India had reported 1.94 lakh cases.

Using the data observed from India’s experience with Omicron now, Agrawal has begun to relook at his model’s earlier projections. He estimates that the peak in India will now arrive by the end of this month and the start of the next and that it will range from four lakh cases in the least to a maximum of about eight lakh new cases. Only Mumbai and Delhi, the two cities that have so far seen the biggest surge, he says, will see a peak between 30,000 to 60,000 and 35,000 to 70,000 new daily cases (on a seven-day average), respectively, by mid-January. Even Kolkata, which has also seen a huge surge, he estimates, will see a similar peak as Mumbai by mid-January.

According to Agrawal, there has been a pronounced loss of immunity in India, especially that developed from an earlier Covid-19 infection. “While the immunity seems to be holding against severe sickness, the loss of immunity towards transmission seems to be a lot more than what was witnessed in South Africa. It’s something that needs to be investigated,” he says.

Agrawal admits the difficulties in making projections currently since the new wave has started only recently and the data is still limited. But over time, he says, this will get more precise. While the new peak will arrive shortly and at a level higher than anything before, Agrawal finds the demand on hospitals will overall be somewhat manageable. At its peak, he estimates, the country will require a maximum of 1.5 lakh hospital beds. Mumbai should require about 10,000 beds at its peak, and Delhi about 12,000. There might be local shortages, and some planning will be required, but overall, Agrawal estimates, the country will be able to get through. “Right now, some estimates in Delhi show that there is about 4 per cent hospitaliation during this wave. Last year, during the peak, Delhi was seeing about 20 per cent hospitalisation in comparison. And it got capped at 20 per cent because people were probably not being able to get hospital beds beyond that,” he says.

Several studies show that while previous infection and vaccination do protect us from severe disease, they do little to stop the infection from Omicron. The earliest clues that Omicron could evade immunity came from South Africa itself where scientists believe at least 70 per cent of people had been infected by Covid-19 at some point earlier in the pandemic. In the UK, according to an article in the New York Times, researchers have estimated that the risk of reinfection with Omicron is about five times that of other variants. A recent Indian paper conducted by researchers from the Translational Health Science and Technology Institute in Faridabad—not yet peer-reviewed—has found that there is a significant reduction in the neutralising antibodies induced by vaccines and the hybrid immunity of vaccines and earlier infections when it comes to Omicron.

Most worry that the rise in the total number of infections might be so extraordinary that even a small fraction of them showing up in hospitals could completely crumble the health infrastructure

In this study, the extent of neutralisation using a measure called neutralisation geometric mean titre (GMT) in 80 individuals was examined. The 80 were divided into groups of 20 each, two such groups having received both doses of either Covishield or Covaxin, and two groups of 20 each who, in addition to the vaccines, were also infected earlier. While the GMT against the original virus strain was found to be 383 for the group that had been vaccinated with Covishield, 384 in individuals vaccinated with Covaxin, and 1,424 and 795 for the groups where people had been infected and received Covishield or Covaxin, respectively. When testing against Omicron, only five out of the two vaccine-only groups, five in the Covaxin-plus-past infection group, and nine in the Covishield-plus-past infection group exhibited neutralisation titres above the lower limit of quantification. “Omicron variant shows a significant reduction in neutralising ability of both vaccine-induced and hybrid immunity-induced antibodies, which might explain immune escape and high transmission even in the presence of widespread vaccine coverage,” the authors write.

Like earlier surges, the largest so far has been in the twin metros of Mumbai and Delhi. Both have breached or appeared close to breaching previous highs, hovering around the 20,000 new daily infections mark (although Mumbai has seen a sharp decline in cases recently), leading officials to announce a slew of measures for restricting movement while ramping up the number of beds and oxygen supply.

“We weren’t surprised when cases began shooting up here because we had been following what was going on in South Africa and Europe,” says Suresh Kakani, the additional commissioner (health) for Mumbai’s municipal body Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation. “We had kept all our jumbo facilities ready and ramped up our facilities. The cases have begun to climb down now, but we are prepared to handle a bigger load.”

According to Kakani, the majority of the infected display few or no symptoms, and only a very small fraction of cases are landing up in hospitals. “In our experience, this new variant appears to be mild. While the transmissibility rate appears to be very high, close to 90 per cent of the patients are asymptomatic. There hasn’t been much load on hospital beds or dependence on oxygen support either. But Mumbai has had a large vaccine coverage, and that might have a role to play,” he says, while pointing out that the majority hospitalised are those who have not been vaccinated.

In Mumbai, after breaching record highs in just days, the daily number of new infections has been witnessing a sharp decline in the last few days, from 20,318 new cases on January 8th to 11,647 cases by January 11th. According to Dr Rahul Pandit, the director of critical care in Fortis Hospitals in Mumbai, and a member of Maharashtra’s Covid-19 Taskforce, it is too early to suggest if the third wave is declining in the city since the number of tests conducted has also fallen over these days.

The testing strategy has, in fact, been altered across the country as case numbers went through the roof. According to ICMR’s latest guidelines, there is marked stress on not testing the asymptomatic, whether these are asymptomatic contacts of confirmed cases (unless they are at risk because of their advanced age or comorbidities) or people about to embark on interstate travel or get admitted to hospitals for other ailments.

“In a situation such as now where nearly everybody is showing mild symptoms and recovering quickly, there is a valid case for not testing too much. You know the asymptomatic will get better anyway. Although there is the risk that the asymptomatic, since not isolated, will spread the infection more,” Agarwal says. “The advantage with such a strategy is that you focus on the symptomatic, and your resources go towards those who need your attention. Plus, a large number of cases create unnecessary panic. To take an extreme example, nobody tests the seasonal flu. If you begin testing, you will find huge numbers of people testing positive during winter. That number really has no value,” he says.

Pointing to the high use of self-testing rapid antigen kits where individuals are expected to self-report themselves in case they turn positive, but rarely do so, Dr Ishwar Gilada, an infectious diseases expert and the secretary general of the Organized Medicine Academic Guild of India, points out that the real number of the infected would actually be a lot more than the current official figure. “The government [bodies] has conveniently turned a blind eye to people self-testing and not reporting their infections. Just look around anecdotally to find out how rapidly this virus is spreading. Every few days, from judicial to Parliament staff to doctor communities, more and more are turning up positive,” he says.

The earliest clues that Omicron could evade immunity came from South Africa where scientists believe at least 70 per cent of people had been infected by Covid-19 at some point earlier

For all the conversation around how mild the symptoms of the current variant are, it poses very real dangers. Most worry that the rise in the total number of infections might be so extraordinary that even a small fraction of them showing up in hospitals could completely crumble the health infrastructure.

There is also every possibility that even when there could be enough beds and oxygen support available, there might soon not be enough doctors or nurses to tend to patients. A vast number of healthcare professionals are turning up positive, and even though they will recover and return to work within a week, the numbers might soon grow to such an extent as to almost cripple hospitals. An Indian Express report on January 9th, for instance, found that at least 750 doctors, and hundreds more nurses and paramedics, in six major Delhi hospitals, were undergoing isolation after contracting the infection. The worst-hit was the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), with nearly 350 resident doctors having tested positive, not including faculty members, nurses, and other paramedical staff. “I keep telling people, the first wave was all about PPE kits and masks, and the second about hospitals beds and oxygen support. This third wave is going to be about healthcare workers. There won’t be enough of them,” says Dr Pandit.

In the hospital Dr Pandit works in, rosters have been designed in such a way that not all doctors are exposed to patients who might be Covid-positive at the same time while also keeping backups of teams of doctors ready so that every time a doctor contracts the virus, someone else will be able to tackle the void. “It doesn’t happen at one go. Every time, when one or two fall sick and join back on the eighth day, the next batch will have gone down,” he says. “At the moment, we are doing okay, but it is still limited manpower. And it is a constant worry.”

Suggesting that out-of-the-box thinking will be required when the deluge hits, Dr Gilada elaborates one will need to consider such steps as having doctors who test positive and are asymptomatic sent to Covid hospitals to care for patients instead of remaining isolated for a week. “Or in the case of infected doctors who are asymptomatic, perhaps we will have to consider reducing the isolation period from seven to five days,” he says. “During the second wave, we saw a surge in about two states first, Maharashtra and Chhattisgarh, before cases elsewhere started shooting up. Here, we have about eight to 10 states showing indications of a major wave.”

“We don’t have the luxury of time,” he adds.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Cover-War-Shock-1.jpg)

More Columns

Jasprit Bumrah Captain? Shubman Gill His Sidekick! Short Post

Our response will be fierce and punitive, says India Open

IAF pounding of air bases, command and military infra forced Pak to seek ceasefire Open