The Art of Eating

How Pandemic has changed our food habits

Kaveree Bamzai and Lhendup G Bhutia

Kaveree Bamzai and Lhendup G Bhutia

Kaveree Bamzai and Lhendup G Bhutia

|

06 Aug, 2021

Kaveree Bamzai and Lhendup G Bhutia

|

06 Aug, 2021

/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Eating1.jpg)

Panta Bhaat (Photo: Rohit Chawla)

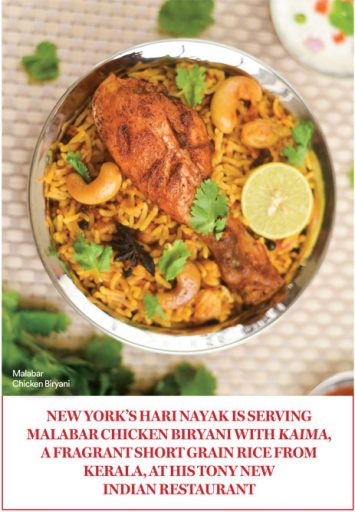

WHERE HAVE YOU BEEN ASKS ONE OF THE JUDGES. Just at home, Kishwar Chowdhury says, weeping into her napkin. When she went on to the grand finale of MasterChef Australia dazzling the jury with the humble Bengali staple panta bhaat, she was embodying the transformation that the pandemic has wrought upon our relationship with food. New York’s rising star chef Hari Nayak is serving Malabar chicken biryani with kaima, a fragrant short grain rice from Kerala, at his tony new Indian restaurant called Sona and wondering why he spent so much time on the design of the crockery and the drama of plating at Jhol, his restaurant in Sukhumvit, Bangkok. Gordon Ramsay is cooking comfort food in his kitchen with his children for YouTube and enjoying every bit of it, without his customary rudeness. And closer home, a home chefs awards show organised by Finely Chopped Consulting and bookaworkshop.com gets 800 entries from across 40 cities.

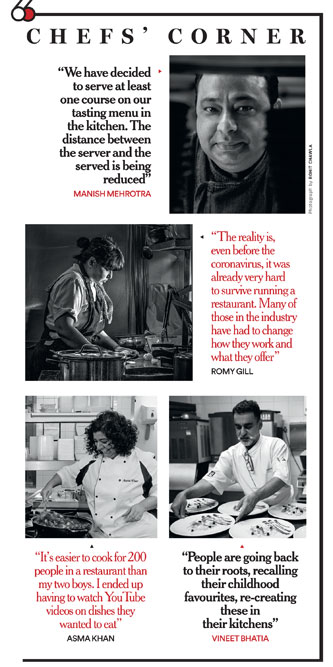

In the last 18 months, Covid-19 may have caused restaurants to shut down, some permanently so, but chefs have been busy. And those who frequented the restaurants have been busier, deprived of domestic help and restricted to their homes. Gone are the foreign ingredients and exotic produce. What’s local and seasonal is right. And on YouTube sessions by chefs at home, it’s not the elaborate preparations that usually take hours but quick and easy recipes that are bringing in the viewers. Says masterchef Vineet Bhatia, one of the few to have kept his restaurant in Dubai going through a major part of the pandemic: “People are now deriving pleasure in the simple things. They are going back to their roots, recalling their childhood favourites, re-creating these in their kitchens, and as the lockdown restrictions ease, re-aligning their dietary habits using more locally sourced ingredients and more plant-based foods. And, most importantly, eating meals together as a family.”

No longer are ingredients being sourced from supermarket shelves but from farms. Everyone is slowly understanding the value and importance of ingredients, seasonality and relationship with the land

That relationship has altered, as has the provenance of the produce. No longer are ingredients being sourced from supermarket shelves but in the rough and tumble of farms. From the farmer to the customer, everyone is slowly understanding the value and importance of ingredients, seasonality, and relationship with the land. For the first time in India, says Indian Accent’s celebrated chef Manish Mehrotra, the back of the restaurant is as important as the front. “We have decided to serve at least one course on our tasting menu in the kitchen. The distance between the server and the served is being reduced,” he says. There are other changes: zero waste, simple plating, and functional service. There is a rise of vegetarianism as well, says Mehrotra, with vegetarians now accounting for more than half the tasting menu, as well as of veganism. “Earlier we had one vegan in a week, now it is three in a day,” says Mehrotra.

For Dhruv Oberoi of Olive, Delhi, the focus is on creating comfortable cuisines with the best of local ingredients. Pomelo salad with local horseradish cream, dill dressing and lotus root crisps. An appetizer made of seasonal tubers served with mushrooms sourced from local farms and served with celeriac grown in the outskirts of Delhi. Pasta made with local sunchoke cream and served with confit fried colocasia (aarbi). Cheese tart made with lime sourced from Hisar Farms and Charoli Almond crust.

Home-style food with homegrown chefs needs homegrown produce. Ergo, farmers like Achintya Anand of Krishi Cress began farming seven years after seeing a gap for microgreens and edible flowers in Delhi restaurants. Now he focuses on marketing and selling, while allowing the farmers at his Faridabad land to do their work, and has been supplying everything from immunity-boosting fruit baskets to turmeric, kombucha, salad mix and avocado. “People were cooking a lot more for sheer pleasure and comfort,” says Anand, whose business after the pandemic has grown by 50 per cent. His aim now is to serve meals at his farm, complete with guests tasting the crunch of the carrots and the sweetness of the peas.

Of the 20 cooking workshops Delhi chef Megha Kohli did, the best response was for her ‘one pot meals’. She taught six dishes across different cuisines that could be prepared in under 30 minutes, using just one pot

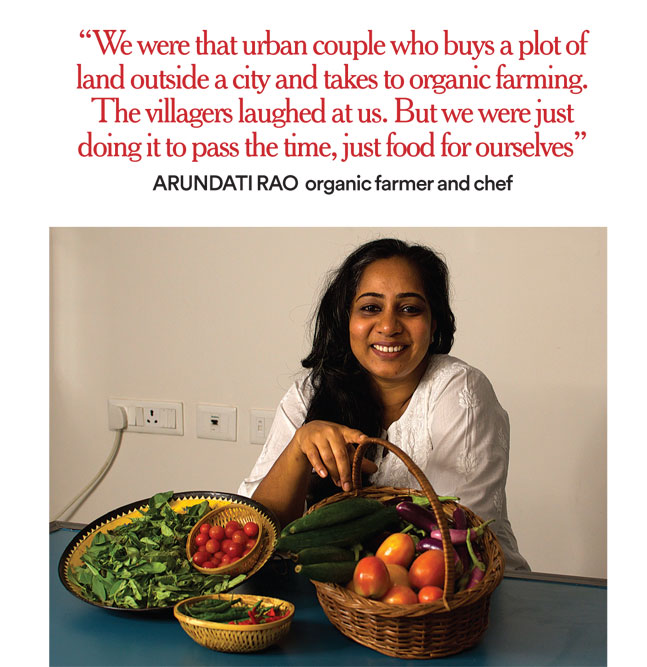

Last year, when the lockdown was announced and Arundati Rao moved to the farm she had purchased along with her husband some years ago, she could not help but feel distressed. Thirteen years had passed since she quit her job at a telecom company in Hyderabad and built a business around her passion of cooking and baking—a culinary studio where she taught her patrons the fine arts in a kitchen. Now it appeared it had all been for nothing. Her studio was going to be one more small business the pandemic would gobble. “It felt terrible,” she says. “I was not ready to let it go.”

That’s when she rediscovered food. Or more precisely, what goes into our meals.

Rao’s farm is located at Chakrampally, a village 65 km from Hyderabad. The couple had purchased about 1.5 acre of agricultural land so that they, along with their dog, could get out of the city and relax on weekends. They had built a kitchen garden there and grown vegetables intermittently.

But with the pandemic raging through the city and the enforced isolation of rural life, with their closest neighbour three kilometres away and the nearest grocery store about 15 km, Rao and her husband rolled up their sleeves and began to take to their kitchen garden.

They grew a wide variety of vegetables, herbs and pulses. Their roughly 300 trees, 40 of them bearing 22 different varieties of mangoes, began to bear fruit. They had peanuts cold-pressed into cooking oil. They began to make jars of hummus, pickles and pesto. Their produce was so abundant that they began bartering it with home farmers like them for things they didn’t grow, such as black rice and sorghum. At one point, the two even considered keeping chicken but dismissed the idea because it would attract snakes.

“We were (the cliché of) that urban couple who buys a plot of land outside a city and takes to organic farming. Initially, the villagers laughed at us saying you can’t do organic farming here. But we were just doing it to pass the time, just food for ourselves,” she says. “The whole experience however changed us completely. It has made me so aware and conscious of the food we eat. Even our taste buds have become sharper,” she says.

In this idyllic life, Rao now plans her daily meals as she walks through her kitchen garden in the mornings, a coffee mug in hand, observing what fruits and vegetables are ready to be plucked, while close to her, her three dogs, two of them adopted over the course of last year, chase butterflies and birds.

With lockdown restrictions being eased, apart from her online culinary classes, she has also begun to travel to Hyderabad a few times every week to conduct smaller one-on-one classes with vaccinated students. She also plans to build a farm-to-table experience around her kitchen garden where she will conduct residential cooking and baking classes. “When we first came here, we thought it was going to be a temporary arrangement,” she says. “But the whole experience of growing our own food has changed us. We can’t think of living anywhere else now.”

For many like her, Covid transformed their relationship with food. When lockdown orders were issued, many began to use whatever space was available, from terraces and balconies to window sills, to build small kitchen gardens to grow their own produce. Businesses like iKheti and Earthoholics which promote urban farming have reported large spikes for their workshops since the pandemic began.

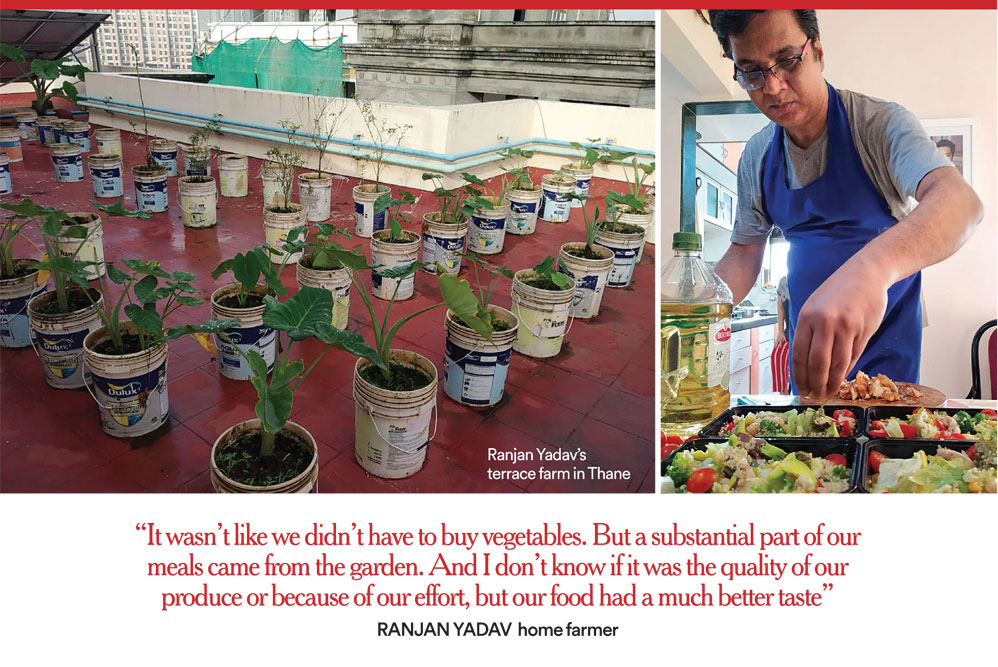

In Thane, a crowded city with matchbox apartments that is part of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region, Ranjan Yadav and three other neighbours began to grow vegetables on the terrace of two buildings in their housing society during the pandemic. “Terraces in housing societies are mostly unutilised. So it’s a great place to try out something like this,” he says. The four of them took the permission of other residents to first establish a small garden using empty paint buckets back in 2017. But when the four of them were stuck at home once the pandemic struck, they began to expand the garden, now totalling about 200 pots and buckets, where they grew a large variety of vegetables and herbs, from brinjal, okra, spinach and green chillies, to basil and thyme.

“It wasn’t like we didn’t have to buy vegetables. But a substantial part of our meals came from the garden,” he says. “And I don’t know if it was the quality of our produce or because of the effort we were putting in, but all of us felt our food had a much better taste.”

With lockdown norms being eased and each of them returning to their jobs, they have continued to care for their garden. Yadav, who has started his own home-chef enterprise, sources quite a few of the ingredients in his meals from the garden.

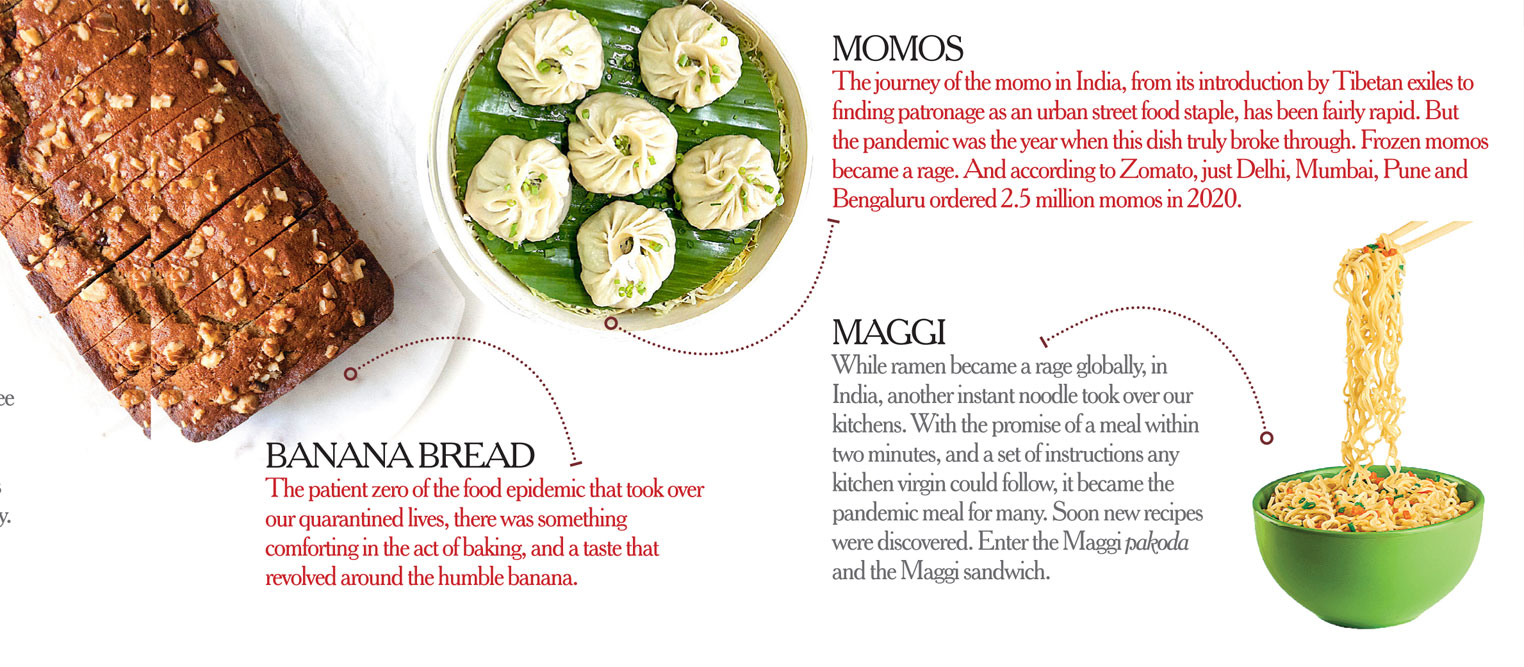

RIGHT FROM THE start of the pandemic, its transformative nature has perhaps been most visible in the contents on our plates. While in the initial period of the lockdown, people hoarded food, and some like Yadav took to urban farming, it quickly gave way to food trends, from the perfect Dalgona Coffee to banana and sourdough bread. It was as though food became a way of coping with the pandemic.

Strange and not-so-strange occurrences began to be reported. Packaged food purchases expectedly shot through the roof. New Maggi recipes were discovered. An old Indian favourite—the humble Parle-G biscuit—was rediscovered and became one of the most sold commodities in the market. Mayank Shah, the senior category head at Parle Products, the company that makes Parle-G, told Open in an earlier interview that it wasn’t just migrant workers who were picking up the biscuit as they walked back home but also middle-class homes which, at this time of anxiety, wanted to return to the taste of an earlier time. A popular priest in Mumbai, Father Warner D’Souza of St Jude’s Church in Mumbai’s Malad East, in a bid to attract more viewers, converted his online sermons into a part cooking show, marrying Bible discourses with recipe tips. “I realised the pulpit can be anywhere, my kitchen too,” he had told Open.

Covid has also brought about new food business opportunities. With the restaurant business among the most severely affected, firms such as Anusaya Fresh, which supply premium vegetables, fruits and frozen food to five-star restaurants, pivoted their business model and began to sell exotic ranges of produce like asparagus from Peru, blueberries from Holland and gourmet cheese from France directly to the domestic consumer through their new premium e-grocery firm Berrika.

Food habits are being rapidly reshaped by the pandemic. The Mumbai-based firm InI Farms, for instance—which is among the largest exporters of premium quality fruits, especially pomegranates, grapes and bananas (exporting over 40,000 tonnes to about 35 countries annually)—has begun to target the domestic market with a renewed focus.

Their fruit brand Kimaye has existed in the business-to-business category for several years, either in the form of exports or placed in retail outlets like Star Bazaar and Foodhall. Last year, they entered the business-to-consumer segment through their online fruit store Kimaye.

A fruit brand is believed to be notoriously hard to sell. Most Indians do not buy fruits based on their brand but on what they see and feel at the fruit stand. But the pandemic has so reshaped habits, with ideas of safety and hygiene paramount in customers’ minds, according to Purnima Khandelwal, the CEO of InI Farms, that the market is ready for the branded fruit concept. “When it came to fruits, the woman of the house usually went to the nearest neighbourhood store or sabzi mandi, picked up a fruit, squeezed it to check its firmness, maybe smelt it, before deciding to buy it,” Khandelwal says. “But there is a change happening now. Customers are asking for certification, they want to know where it is from, how it has been handled.”

Each Kimaye fruit is also a story in itself. To satiate the newfound interest in the food we are consuming, each fruit now comes with a QR (quick response) code which, when scanned, tells the consumer about the farmer who grew the fruit, the name of the village and state he hails from, and what else he grows, while detailing the journey of the fruit from the time of harvest to the moment it reaches the consumer.

Most people were shopping less often now and making meals with what they had, using leftovers, planning menus, wasting less. They were finally realising their ‘finite’ relationship with food.

Of the 20 cooking workshops that young Delhi chef Megha Kohli did, the best response she got was for her “One Pot Meals” where she taught six dishes across different cuisines that could be prepared in under 30 minutes, using just one pot. Always a hands-on chef, working day in and out in a restaurant and professional kitchen since she joined this industry at the age of 17, her biggest learning thanks to the lockdown and pandemic was this—you don’t need a restaurant to spread the joy of food. She left her job in March 2020, and her next project got indefinitely delayed because of the pandemic. “But I (like most chefs) started sharing recipes through my IGTVS, my workshops and I was blown away by the response that I got from my very first recipe shared on Instagram. My food has reached so many homes via social media and I established a personal connection with people across the globe who were cooking my recipes and writing to me to clarify their doubts, share their excitement when a dish turned out well, and share pictures of their family enjoying the dishes. The response was overwhelming.”

The restaurants, if at all they were open, were all operating on reduced à la carte menus and suddenly less was more. Says Vineet Bhatia: “It had really spiralled out of control in the last few years as diners expected the chefs to pull out some tricks from their hats rather than just provide wholesome, freshly cooked meals. There was so much (unnecessary) drama, often non-food related, that this re-calibration is a fresh welcome, a fresh start to the restaurant scene that is fighting hard to survive.”

Thanks to the lockdown, appreciation for home-cooked, comfort food has grown. Simple recipes were searched more online than complicated ones. Some of the highest viewed recipes on Kohli’s Instagram have been dal makhani, fish curry, butter chicken, chole bhature, rajma chawal and pao bhaji. People were going back to their childhood recipes, to seek comfort in this new uncertain pandemic-stricken world. Even at Sona, where chef Nayak presides, celebrity partner Priyanka Chopra Jonas, who tasted much of the menu, insisted that one thing remained on the menu—golgappas, even if they came with avocado and tequila.

Home chefs came into their own as well since they were the first source of food coming in from outside after a long time. The support of distribution apps helped. There was a general sense of fear all around and the thought that the food was coming from someone’s home was reassuring. Things improved with time and there was competition but consumers had got a taste of the wonderful food on offer and home chefs had got a taste of how they could change their own lives through this endeavour and hence the movement continued to grow, says food writer Kalyan Karmakar. “We had instituted the Home Cheffies Awards to recognise and support brands emerging in the sector. It was the first-ever pan-Indian home chef awards event and the jury consisted of industry leaders and brand custodians from the corporate world. Winners got cash prizes and got to feature in the first-ever Home Cheffies Guide,” he says.

FOOD BECAME THE only source of joy during this period for many, a family binder and source of activity, and the kitchen became the centre of our universe like never before. Asma Khan, whose Darjeeling Express restaurant in London experimented with the idea of home chefs cooking in a public domain much before the pandemic, agrees. The biggest change that happened during the pandemic, she says, was that after many years she found herself at home with her two children, 21 and 16, and having to cook for them. “I can just say that it’s easier to cook for 200 people in a restaurant than my two boys because they were very excited to finally have me home and cooking. I ended up having to watch YouTube videos on dishes they wanted to eat because I didn’t know how to make them. I did lasagna from scratch; I did tacos and many variations of the Calcutta Hakka Chow. There were, as everywhere around the world, shortages of supplies, and I was fortunate to discover an egg farm that would post 100 eggs to you. My lasting memory of the pandemic has to be the odd combinations of things my son would stuff his omelette with and then make me eat half of it. I am grateful that I got the chance to be a mother again as I have missed eating meals with my children over the last five years.”

Ditto for Mehrotra, who says planning four meals for home was one of the biggest challenges of his life. Yet it was also a comfort, says chef Romy Gill, given that the hospitality and food and drink industry was one of the worst hit, with high rents still to pay despite being closed. “The reality is,” she says, “even before the coronavirus, it was already very hard to survive running a restaurant. Many of those in the industry have had to change how they work and what they offer to ensure that they survive beyond lockdown. Some restaurants have turned to takeaways and delivery services for the first time, local pubs have reopened as grocery shops and wholesalers to the catering industry have now made their products available to the general public. For the restaurant industry, which I was in for so many years, it’s a truly challenging time, and I know many restaurant owners are unsure whether their businesses will even survive after the pandemic.”

Gill’s relationship with food changed a lot. She went back to her roots while growing up in Burnpur, where they depended on local, seasonal and sustainable produce. Her work is now focused on writing and her TV career. She shared over 100 recipes during the lockdown and raised over £10,000 for different charities cooking from home.

And for every home that was well stocked with fruits and vegetables, there was a small businesswoman somewhere earning a living. Take the venerable Ahmedabad-based food scholar Esther David. Throughout the pandemic, there was a vegetable vendor, Kantaben, who came to her home every alternate day with fresh vegetables. Pinkyben brought fresh fruit every week. They called David regularly, from their mobiles. The chowkidar of the housing society next door, Kantibhai, went shopping early in the morning and bought milk and two big loaves of bread. She toasted the bread and kept it in the fridge with packets of butter. So, every morning, she had tea and toast, as she read the newspaper. She cooked regular meals, which she has been doing for years. She had frozen chicken pieces and made them every Sunday for lunch. “I also had eggs once a week. And, for my 5PM snack with tea, I made chivda for myself and had cream-cracker biscuits,” she says.

Flavourful, elegant, with little flourishes, and based on what was available. If the pandemic were a series of small plates, this would be the ideal table.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Cover_Kumbh.jpg)

More Columns

What does the launch of a new political party with radical background mean for Punjab? Rahul Pandita

5 Proven Tips To Manage Pre-Diabetes Naturally Dr. Kriti Soni

Keeping Bangladesh at Bay Siddharth Singh