Tamil Nadu: Getting it Right

Why BJP is upbeat in Tamil Nadu about next year’s Assembly elections

Maalan Narayanan

Maalan Narayanan

Maalan Narayanan

Maalan Narayanan

|

16 Oct, 2020

|

16 Oct, 2020

/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Gettingitright1.jpg)

Khushbu Sundar (Courtesy: Avni Cinemax)

PONDY BAZAAR, THE ever-bustling main marketplace in the heart of Chennai, was relatively quiet on September 17th. A horsedrawn carriage was parked in the street. Flashily dressed men and women, sequins glistening on their clothes, were waiting to break into dance. Suddenly, crackers boomed. The beats of the parai, a drum once associated with Dalits and now a symbol of rebellion, filled the air. This was no wedding procession—it was a welcome for L Murugan, the president of the BJP’s Tamil Nadu unit. Despite the ban on political events to curb the spread of Covid-19 in the state, Murugan was being taken around in the carriage to his office two blocks away, where a 70ft-long cake was waiting to be cut to commemorate the 70th birthday of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Such ostentatious displays by Dravidian parties are not uncommon, but for the BJP in Tamil Nadu, it was a first.

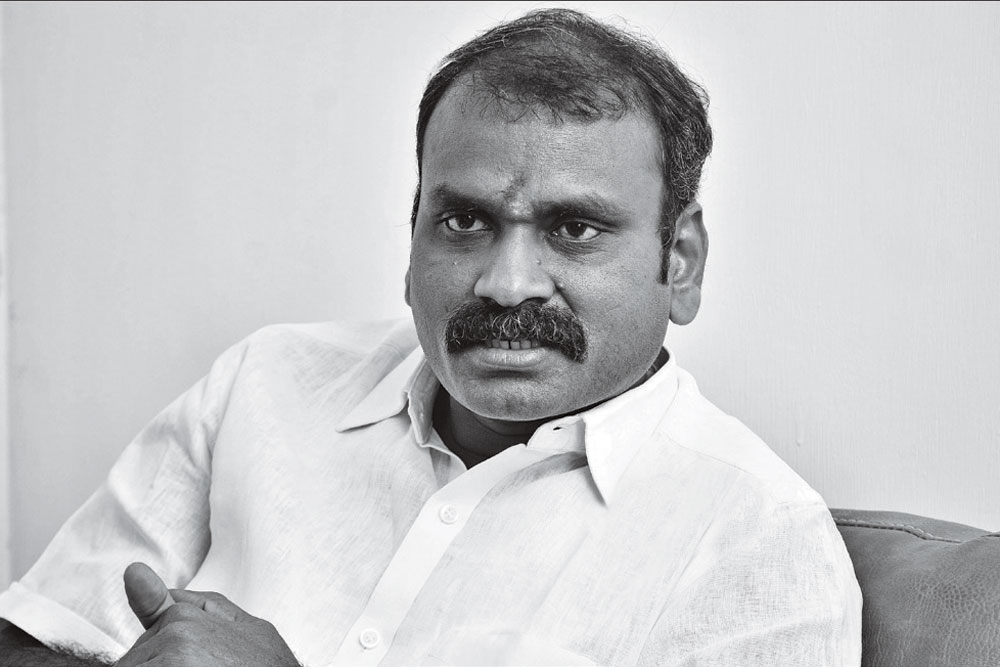

Murugan, 43, a Dalit lawyer with a master’s in international law, was a surprise pick by the BJP high command, which had been dithering for over seven months to fill the vacancy left by Tamilisai Soundararajan upon her appointment as Governor of Telangana. The choice of Murugan, a political novice, was surprising, and not only because he had pipped former Union minister Pon Radhakrishnan and senior leaders H Raja and Vaanathi Srinivasan to the post. With the Tamil Nadu Assembly elections not far away, it was not without a mission that Murugan was chosen. It was the first of many steps to recast the image of the BJP—perceived by many in Tamil Nadu as an upper-caste, urban, north Indian party—vis-à-vis Dravidian parties. Murugan, sources say, was asked to build a base for the BJP among Dalits, who have cast their lot with splinter groups. It is to be noted that neither of the Dravidian majors has a Dalit at the helm of affairs.

Murugan has begun his mission with the bang of the parai. Soon after his induction in March, he was able to rope in VP Duraisamy, former Deputy Speaker of the Assembly, from the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK). He has been accommodated as a vice president of the state BJP unit. And when he reconstituted his team of state office bearers, Murugan picked candidates from Other Backward Classes (OBCs), sidelining Brahmins. There is not a single Brahmin among the 11 state vice presidents or the four state general secretaries. But for KT Raghavan, all are OBCs. This is not unusual. In fact, the last Brahmin president of the state BJP was L Ganesan, who held the party reins over 15 years ago.

But it is to be seen whether the Uttar Pradesh model of social engineering will yield results in a land that values Tamil and Dravidian identities over caste pride. It is perhaps with this in mind that the BJP’s Tamil Nadu unit has drawn heavyweights from the Dravidian parties to its fold in recent years. VP Duraisamy, a former Deputy Speaker; Nainar Nagendran, a former All India Anna DMK (AIADMK) minister; A Bhaskar, a former Desiya Murpokku Dravida Kazhagam (DMDK) MLA; and P Karthiyayini, former Mayor of Vellore from the AIADMK have all been accommodated in plum posts in the state BJP.

K Annamalai, an IPS officer perceived to be actor Rajinikanth’s close associate, was catapulted to the position of state vice president within three days of his joining the party.

Glamorous faces from tinsel town have also found their way into the BJP. Actor-turned-politician Khushbu Sundar, who was a prominent Congress face in Tamil Nadu and is a self-professed Periyarist, is the latest

R Srinivasan, another state vice president of the BJP, defends these appointments as “lateral insertions”. He tells Open: “Earlier, senior leaders from other parties were reluctant to cross over to the BJP. The hopping was taking place between the DMK and the AIADMK. Rangarajan Kumaramangalam and Su Thirunavukkarasar were exceptions. Rangarajan joined us from the Congress and Thirunavukkarasar merged his party with us. Both of them were given ministerial berths in Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s Government. Now, because of the BJP’s growing presence, senior leaders from other parties are joining the BJP. Considering their political work for decades at the ground level, the BJP would not find it proper to ask them to start from scratch. These lateral insertions are natural and inevitable for any party that is gaining ground.”

Glamorous faces from tinsel town, too, have found their way into the party. Actor Namitha Vankawala, who joined the BJP in 2019, was made a member of the state executive. Another starlet, Gayathri Raghuram, who made ripples in the Bigg Boss series, who had been expelled from the party by Tamilisai Soundararajan, has been appointed secretary of the cultural wing of the party. Infamous for his alleged misogyny, actor Radha Ravi, too, is a party member, even if he does not hold a position. His father, actor MR Radha, was a staunch loyalist of Periyar EV Ramasami. Another new face in the BJP, actor-turned-politician Khushbu Sundar, who was a prominent Congress face in Tamil Nadu, is a self-professed Periyarist (she played the role of Maniammai in the 2017 biographical film Periyar).

Periyar, the rationalist founder of Dravidian ideology, remains a challenge for pro-Hindutva BJP. It is neither able to dismiss him outright nor accommodate him. It is an interesting irony in history that Periyar and Narendra Modi share their date of birth. During the birthday celebrations of Modi, television mics popped up before Murugan and he was asked why he has not extended greetings on the birth anniversary of Periyar. Without hesitation, Murugan responded, “There is no second opinion that Periyar worked for social justice. We have no hesitation in extending our greetings to him.” Later in the evening Vaanathi Srinivasan, a vice president, toed a similar line in a TV debate. Murugan’s remark is significant because it is for the first time that a state BJP president has spoken positively about Periyar.

With the Tamil Nadu assembly elections not far away, it was not without a mission that the BJP chose L Murugan, a Dalit lawyer, for state president. It was the first of many steps to recast the image of the BJP vis-à-vis Dravidian parties

BJP seniors don’t approve of what appears to be a strategy to use fresh thinking on Periyar to woo the Dravidian votebank. S Gurumurthy, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) ideologue and editor of the weekly Thuglak, has reminded the party of the damage that associating with Periyar caused the Congress in the 1967 elections. In 1967, Periyar had publicly backed the Congress and Kamaraj’s leadership, going to the extent of dubbing the anti-Hindi agitation led by the DMK as “riots by anti-social elements”. Gurumurthy points out that the nationalist votes which traditionally went to the Congress migrated to the DMK alliance. Periyar was perceived to be against nationalism. The Congress lost power in that election and has never won again so far.

It was not long ago—on December 25th, 2019, the anniversary of Periyar’s death—that the BJP’s IT wing had stoked controversy with a tweet on his personal life. At the age of 69, Periyar had married 31-year-old Maniammai. “Today is the death anniversary of Maniammai’s father Periyar. Let us support the death penalty for people who sexually assault children and take the pledge that we will create a society without any Posco accused,” the BJP had tweeted, before quickly deleting it in response to severe criticism from alliance parties including the AIADMK and the Pattali Makkal Katchi (PMK). The incident, seen alongside Murugan’s instantaneous response on Periyar, suggests the Tamil Nadu BJP is in a dilemma over the question of acknowledging him.

Aside from the bind over ideology, the BJP’s alliance with the AIADMK, too, is not in the pink of health. With AIADMK ministers and BJP functionaries trading potshots, VP Duraisamy declared on August 30: “We are growing fast in Tamil Nadu. Likeminded parties would be part of the alliance. We will lead them because we are a national party.” The next day, Murugan said the BJP has “chances of victory in at least 60 constituencies even if it contests alone”. But with Modi praising the AIADMK’s governance and announcing they would be talking about power sharing after the elections, the state BJP chief had to tone down. It is no secret, however, that the party is hoping for Rajinikanth’s arrival in the electoral arena.

OPS was handpicked by Jayalalithaa thrice whenever she could not be chief minister. EPS was Sasikala’s choice when OPS rebelled against her after Jayalalithaa’s death. But the real tussle now is not for the chief minister’s chair but for the reins of the party

SINCE AUGUST 15th, the AIADMK had been in the midst of a fratricidal cold war over the chief ministerial candidate for the upcoming Assembly elections. Secret parleys for and against the key aspirants, incumbent Edappadi K Palaniswami (EPS) and former Chief Minister O Panneerselvam (OPS), take place every day. The factionalism came out in the open with the recently held party executive meeting, which turned into a slugfest between EPS and OPS loyalists. OPS was handpicked by Jayalalithaa thrice whenever she could not remain in the seat due to imprisonment on corruption charges or health reasons. EPS was Sasikala’s choice when OPS rebelled against her after Jayalalithaa’s death.

But the real tussle now is not for the chief minister’s chair but for the reins of the party. The AIADMK faces an uphill battle in the Assembly elections, with several factors including anti-incumbency, internal instability and the absence of Jayalalithaa spelling trouble. The DMK has been painting the post-Jayalalithaa AIADMK as Modi’s pawn. Some of the Centre’s decisions such as going ahead with the national medical exams, attempts at making Hindi compulsory and the National Education Policy 2020 have been projected by a section of the media as anti-Tamil and the AIADMK government being inept at handling the issue. In this context, power in the party rather than in government becomes crucial. The stalemate came to an end after over 50 days, with the constitution of an 11-member Steering Committee to guide the party and nominating EPS as the chief ministerial candidate for the Assembly elections.

Infighting is not uncommon in the AIADMK. Even while MG Ramachandran was alive, Jayalalithaa faced opposition from the RM Veerapan faction. This ultimately led to the fall of the government after MGR’s death. The party split and both factions contested the 1989 Assembly elections without MGR’s two-leaf symbol. After elections, the factions merged and Jayalalitha became the supremo. Even so, unable to stomach her style of functioning, splinter groups such as the one led by Thirunavukkarasar left the party to form their own outfits. After Jayalalitha’s demise, the party broke again, with TTV Dinakaran, Sasikala’s nephew, launching a party. These splits were not owing to ideological differences; they were outcomes of power struggles between leaders. Now, with Sasikala likely to be released from prison in January, there could be further splits in the AIADMK, since neither EPS nor OPS is willing to accept Sasikala or Dinakaran back into the party.

With Sasikala likely to be released from prison in January, there could be further splits in the AIADMK, since neither EPS nor OPS is willing to accept Sasikala or her nephew Dinakaran back into the party

The DMK, meanwhile, is brimming with confidence. Party units at the grassroots are already in campaign mode. Thanks to Prashant Kishor’s Indian Political Action Committee, the party has improved upon its optics. The DMK also claims that its recent online membership campaign has evoked an overwhelming response. More importantly, the DMK alliance, which swept 38 of 39 Lok Sabha seats in the 2019 elections, appears to be intact. The allies are already putting pressure on the DMK to share more seats with them. Tamil Nadu Congress Committee President KS Alagiri’s remarks have indicated that the Congress might push for a larger share in power; the Viduthalai Chiruthaigal Katchi (VCK) may follow suit.

In January, the Congress and the DMK were at odds with each other, with Alagiri alleging that his party was not allotted a fair number of posts in local bodies, to which elections had just been held. The DMK had gone against “coalition dharma”, he said. In response, the DMK boycotted the all-party meeting convened by the Congress on the Citizenship (Amendment) Act. DMK General Secretary Duraimurugan did not mince words when he said, “We are not bothered. If the Congress leaves the alliance, we are not the losers. The Congress has no vote bank in the state.” But with the Assembly elections approaching, the parties appear to have patched up.

Strategies and campaigns aside, history shows that electoral arithmetic is an important factor for political parties in Tamil Nadu—and more so for the DMK. In the 2016 Assembly polls, the DMK alliance missed power by a whisker. The difference in the votes polled by the AIADMK and the DMK alliance was just 1.03 per cent, with the AIADMK bagging 1,76,17,060 votes and the DMK alliance polling 1,71,75,374. It is widely believed that the spoiler was the Third Front, a coalition of the DMDK, the Marumalarchi DMK, the VCK and the Communists.

Elections, like the cricket premier leagues, have become a game of glorious uncertainties. Tamil Nadu is no exception.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Cover-War-Shock-1.jpg)

More Columns

A Trump Shock To The Pharma World Open

Social Media As an Echo Chamber Nandini Nair

Seventy-two Hours That Changed South Asia VK Shashikumar