Perfumes and Prophylactics

Smell has always played a critical role in dealing with sickness and cure

/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Perfume2.jpg)

Calendar prints of colognes

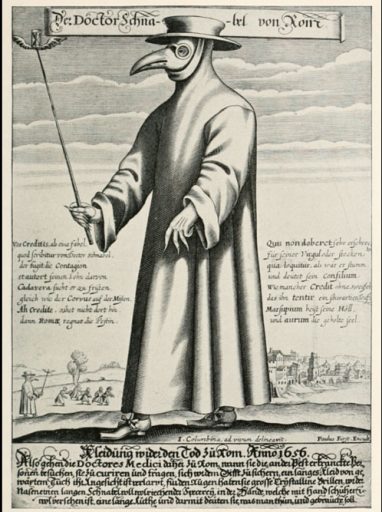

The one theme that dominates the accounts of every plague chronicler is the stench. In fact, miasma, or noxious vapour, was considered to be the main cause of plague by medical professionals. The plague doctor’s costume was designed to hold vials of sweet-smelling herbs. The beak in the costume was meant as a holder, where the vials would be placed. Rosemary and lavender were often used as plague preventives. Other preventives involved the burning of tar, pitch, niter, and of course frankincense. The 1665 publication from the London College of Physicians, Certain Necessary Directions for the Prevention and Cure of the Plague, recommended washing and gargling with vinegar, ingesting copious amounts of treacle, and treating the water with herbs like rosemary, lavender, sage, etc. to keep the plague at bay.

Across the globe, good smell has been a fundamental component of treating infections. Medics have relied heavily on their olfactory abilities to determine the ailment as well as find the cure.

There is a Buddhist fable called Purnavadana that revolves around Purna, a sandalwood merchant. Purna is the illegitimate son of a servant girl and Bhavaka, the merchant. Bhavaka gives Purna a small amount of capital to start his own business. While Bhavaka’s legal sons who have total backing only seem to lose money, Purna does surprisingly well. He invests in sandalwood and when the king of the territory falls sick, his sole cure is sandalwood paste. Purna’s success makes other merchants run to the sandalwood forest, only to realise that there is a yaksha guarding it. Of course, the merchants seek Purna’s help, who negotiates with the yaksha and later uses the sandalwood to build a pavilion for the Buddha. Of course, this is primarily a story about the Buddha and his disciples, since later Purna becomes a Buddhist monk. However, Purna is also a wise merchant who understands the medical marketplace and makes money by selling a cure.

Sweet-smelling herbs, plants, and flowers have always been associated with curative powers. The Atharva Veda mentions a fairy named Guggulu who is in charge of perfuming a plant. Very likely, it is a myrrh plant, a major perfuming agent with numerous medicinal properties. Myrrh and frankincense we have forever used smell to treat diseases across the globe. Although, as historian James McHugh correctly observes, the Sanskrit olfactory lexicon is rather unique. Once again, we have to remember that the use of aromatics as prophylactics transcends cultural boundaries.

Apothecaries and doctors offered their medicines in many forms including pastes, pills, syrups, and potions mixed with honey. Cordials were an important part of treatment. Making a cordial involved the art of distilling. Herbs, fruit juices, and nuts were made into cordials which could be both alcoholic and non-alcoholic. Non-alcoholic distillation led to essential oils

Materia Medica, a practical text dealing with medicinal use that included more than 600 plants, was tentatively composed in 65 AD; but in all likelihood, it was the result of a long, ongoing project whose composition is credited to Dioscorides. The original text is lost but many references to the book survive. Dioscorides’ texts formed the basis of much of the herbal medicine practiced until 1500 AD. In fact, it is still relevant today. Some plants were used for specific disorders, while others were credited with curing multiple diseases. In many cases, preparations were made of many different herbs. Headache and joint pain were treated with herbs and flowers like rose, lavender, sage, and hay. Also, a tincture of henbane and hemlock was applied to aching joints. Coriander was used to reduce fever. Stomach pains and digestive disorders were treated with wormwood, mint, and balm. Lung problems were treated with a medicine made of liquorice and comfrey. Cough syrups and drinks were prescribed for chest, head colds, and coughs. Vinegar was widely used as a cleansing agent for wounds as it was believed that it would kill disease. Mint was used in treating venom and wounds. Myrrh was used as an antiseptic on wounds.

Bald’s Leechbook, a medical text dating roughly around 900-950 AD, recommends smelling herbs and vapour baths as cures for several ailments. The book contains graphic details of treating hemorrhoids, stitching wounds with silk, and fixing fractures, amongst many other things. Like other medical texts, it also includes a large list of different poultices. Fragrant herbs and strong smells always played a major role in making poultices. They often included a nettle-based ointment with myrtle, chervil, fennel, etc. The book was clearly meant for local practitioners and the herbs were readily available.

Apothecaries and doctors offered their medicines in many forms including pastes, pills, syrups, and potions mixed with honey. Cordials were an important part of treatment. Making a cordial involved the art of distilling. Herbs, fruit juices, and nuts were made into cordials which could be both alcoholic and non-alcoholic. Non-alcoholic distillation led to essential oils. The alcoholic versions were the origins of some very popular, modern liqueurs, such as Amaretto, whose almond flavour actually comes from apricot pits; Benedictine, which has 75 ingredients; and Sambuca, a combination of elderberry and flowers. Many cordials contained absinth juice. The poor could not afford any of this. They stuck to remedies like onion, garlic, and vinegar, and these three ingredients were always the fundamental elements of medieval medicines.

Theriac, a medicine originally designed by the Roman physician, Galen to fight snakebite, made a comeback during the plague, after undergoing numerous modifications. It was a thick, syrupy concoction that contained around 80 different herbs, wine, honey, and opium. The basic concept of theriac is not different from the Indian Chavanprash, a health pap credited to the sage, Chavana. It is a mixture of numerous herbs and Indian gooseberries (amla), sweetened with jaggery. Both of these wonder health products depended heavily on olfactory abilities. While, I am not questioning their medicinal properties at all, I want to reiterate that smell has always played a critical role in dealing with sickness and cure.

When Sir Edwin Chadwick decided that filth was the cause of every disease roughly around the late 1840s after England witnessed cholera outbreaks, he was solely guided by olfactory considerations. Miasma was again blamed for causing cholera and cleaning up sewers and cesspools became the cornerstone of the sanitation movement. In his report, The Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain of 1842, he talks about the, ‘disagreeable smell…air was full of most injurious malaria’—back then, malaria meant bad air. Sir Chadwick further insisted that the poor had vices which led to the creation of filth, and all diseases would vanish if they could get rid of the filth that caused the stench. In many ways, Sir Chadwick’s problematic views deeply affected the broader understanding of poverty.

In 1817, the Bengal Medical Board recommended a comprehensive treatment for cholera. The treatment involved strong-smelling herbs, including asafoetida, borax, aniseed, ginger, and cloves. Further, it was advised during the cholera pandemic that every family should keep peppermint oil in their pantry. Water mixed with a few drops of peppermint oil could help prevent cholera. Laudanum and other opiates played a major role too. In fact, massive doses of opiates were often used in tonics and other prophylactics right up to the 20th century. Even medications for children were doused with heavy amounts of alcohol and opiates. Opiates were clearly recommended to relieve pain; the strong-smelling components were seen as the real cure.

When Joseph Burnett’s company, whose claim to fame was making artificial flavourings like vanilla, almond, rose, nutmeg, etc., started publishing the Woman’s Floral Handbook, they decided to teach women the language of flowers and categorised smelling good as a quintessential feminine trait. These handbooks also functioned as almanacs that addressed women’s concerns, like the best lunar position to try skin care regimens, and so on. The handbook first associated specific flowers and plants with emotions and qualities, like cobaea with gossip, dandelion with coquetry, hollyhock with fruitfulness, along with others. They then used this symbolism to sell their cologne water, hair wash, cure for chapped hands, and other cosmetics. Burnett also sold handkerchief perfumes that contained a combination of many flowers. Another popular product was ‘elixir for teeth and gums’ that had astringent properties and fresh taste. The handbooks also included love charms, magical powers of different flavourings, etc. Later, Agatha Christie used floral symbolism in some of her murder mysteries.

While Burnett was fairly well established by the 1850s, another apothecary named Eli Waite Hoyt created his own brand of cologne in 1868. Hoyt’s used scented ‘ladies calendars’ to appeal to women. Even though, cologne water as such was not gender specific, it was fairly clear that women were the chief target. Burnett had discovered how best to appeal to women.

Thus, perfumes played a critical role in fighting ailments and their significance increased greatly during pandemics. John Davies described the mass of plague victims in his 1603 account of the London plague as ‘lanes that vomit their undigested dead,’ and this image clearly gives us a graphic idea of the stench. Historian Holly Dugan mentions the use of pomanders, womb fumigators, and perfumed pessaries as plague cures. A pomander is a ball made of perfumes, namely ambergris, an oily, grey lump that is found on the ocean surface since it is excreted by sperm whales after they have fed on cuttlefish. Ambergris played a major role in Arab perfume recipes as well. Alternatively, almanacs often gave a cheaper option for making pomanders by inserting cloves into an orange.

The idea of womb fumigation is perhaps the reason behind associating women with perfumes. The womb was considered to be the second nose that was repulsed by bad smells. Lizzie Marx maintains that womb fumigation was practiced since at least 2000 BC. Later, douching became the new form of fumigation. However, the idea was always the same; women had to take extra precautions to smell good. Today, we know how dangerous it is for women to douche or even use a perfumed pessary, but monitoring the smell of the feminine body has always been a social fixation. And naturally, pandemic measures often included exerting control over female reproductive health and sexuality.

Finally, I want to mention the film Aiyya (2012), in which the protagonist Meenakshi, played by Rani Mukherjee, falls in love with a man named Surya solely based on how he smells. Throughout the film, she keeps following his scent and discovers the secret of his perfume in the climax. His secret is abir or gulaal, the coloured powder whose original composition contained sandalwood, rose petal, turmeric, cardamom, cloves, and zedoary (white turmeric). Both critics and audience found the theme of olfactory overload to be ridiculous. Yet, can we really blame Meenakshi for chasing this perfume, even if Surya’s abir contained even half of those ingredients? How do you resist that fragrance?

/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Cover-AfterPahalgam.jpg)

More Columns

The Logic of Grace: On the Election of Pope Leo XIV Open

Rubio asks India, Pak to de-escalate but asks Sharif to stop support to terrorism Rajeev Deshpande

Pakistan Launches Another Wave of Attacks on India Open