Best of Books 2024: My Choice

Pratap Bhanu Mehta | William Dalrymple | David Davidar | Aatish Taseer | KR Meera | Ira Mukhoty | Manu S Pillai | Arvind Krishna Mehrotra | Sonam Ahuja Kapoor | Konkona Sen Sharma | Saif Ali Khan | Amit Chaudhuri

/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/PBM1.jpg)

Pratap Bhanu Mehta

Pratap Bhanu Mehta, Political scientist and columnist

This was another year with an embarrassment of riches. But here are some that engage the heart, mind and imagination.

For sheer reading pleasure, the magnificence of the prose and moral subtlety, Richard Flanagan’s blend of memoir and history Question 7 (Vintage) was unsurpassed. Flanagan is amongst the greatest living writers (his Gould’s Book of Fish is remarkably underrated) and he writes about the biggest themes: Hiroshima, the dark side of Australia’s history, what it means to contemplate extinction, the redemption of ordinary life, all via intriguing personal, literary and scientific vignettes. Almost every sentence in this book is startlingly beautiful. Another reading pleasure was the philosopher Simon Critchley’s On Mysticism: The Experience of Ecstasy (Profile Books). Although parochial in dealing only with Christian Mysticism, the clarity and beauty of the prose on a subject that can easily devolve into kitsch, is quite remarkable.

William Dalrymple’s The Golden Road will be on most lists this year: a well-judged antidote to historical amnesias of both the Left and the Right

The most impressive piece of intellectual history this year was Dalpat Singh Rajpurohit’s Sundar ke Swapna (Rajkamal). Through an examination of the poet Sunderdas and his milieu in the early Bhakti movement Rajpurohit gives one of the subtlest accounts of early intellectual modernity in India, upending so many false binaries that have afflicted Indian intellectual history, especially that between Vedanta and Bhakti. This book is a powerful blend of philosophical analysis, poetic insight and social history. William Dalrymple’s The Golden Road (Bloomsbury) will be on most lists this year, and deservedly so: a beautifully written, erudite and well-judged antidote to historical amnesias of both the Left and the Right.

As Palestine and Lebanon lurch into a brutal war and the world moves to authoritarianism the shadows of two writers the world lost this year loom large: Elias Khoury and Ismail Kadare. It was a good year to revisit them. For non-Indian history, Chen Jian’s magnificent biography of Zhou Enlai (Harvard University Press) is a good window into Chinese history that can be read in tandem with India’s leading interpreter of China, Vijay Gokhale’s Crosswinds: Nehru, Zhou and the Anglo- American Competition Over China (Vintage). Indonesia is a country Indians should know better and David Van Reybrouck’s Revolusi: Indonesia and the Birth of the Modern World (Norton) is a riveting narrative history.

William Dalrymple, Author

Disrupted City (The New Press) by Manan Ahmed Asif is a learned and lyrical elegy—or shahr ashob—for the great city of Lahore: a book that is both nostalgic and scholarly, nuanced and cosmopolitan yet deeply rooted, sharpened by a sense of belonging, and at once weighed down and informed by the anchor of memory and attachment, and written by one of the most outstanding historians-flaneurs of our time.

Pankaj Mishra’s The World After Gaza (Penguin) does what great writing is meant to do: to remind us of what it is to be human, to help us feel another’s pain, to reach out and make connections across the trenches of race, colour and religion. By a long way the most thought-provoking book I have read this year.

Mukund Padmanabhan’s The Great Flap of 1942 (Vintage) is a superbly well researched, tightly constructed and beautifully written exploration of an almost forgotten chapter in the history of the Second World War. It is a brilliant recreation of a particular time and place, effortlessly pinned to the page in stylish, witty and evocative prose. Padmanabhan, long regarded as one of India’s most admired journalists and editors, has now emerged from that chrysalis to reveal himself as a new superstar of Indian narrative nonfiction.

Pankaj Mishra’s The World After Gaza does what great writing is meant to do: to remind us of what it is to be human, to help us feel another’s pain, to reach out and make connections, says William Dalrymple

Whole libraries have been written on Rama, the Ramayana and the question of the historicity of the most popular of the South Asian epics, but the legacy of Ravana is less well known and much less thoroughly researched. In Ravana’s Lanka (Vintage), Sunela Jayawardene searches her beloved island for evidence for Rama’s greatest adversary—and comes to a series of fascinating, thought-provoking and often surprising conclusions about his realm. At once a deeply personal quest for the roots of a nation, and an exploration for the meaning in a myth, Ravana’s Lanka is also a beautiful written celebration of one of the most beautiful islands on earth and of its diverse peoples.

Eugene Rogan is arguably our greatest living historian of the Middle East. His books on the Palestinian Nakba, the Ottomans and the Arabs are essential reading for anyone trying to understand one of the most complex regions of the globe with its many simmering conflicts. His new book, The Damascus Events: The 1860 Massacre and the Destruction of the Old Ottoman World (Allen Lane) examines in detail one of the most terrible outbreaks of communal violence in Ottoman history. It is superbly well researched and beautifully written, with all the archival discoveries and subtle, nuanced interpretation that we have come to expect from Rogan. But it is also a deeply humane book that provides a much-needed example of how societies with deep divisions can pull back from the brink. It shows how they can and do recover from the trauma of genocidal violence, finding a way to stagger back towards tolerant coexistence. It is difficult to think of a more timely or important history book published this year.

Finally, Manu S Pillai’s Gods, Guns and Missionaries: The Making of The Modern Hindu Identity (Allen Lane) is a brave and magnificent book, and a vital intervention: as elegant as it is witty, as erudite as it is wise, and as stylish as it is scholarly. Pillai is fast becoming one of India’s most accomplished and impressively wide-ranging historians.

David Davidar, Publisher, novelist, and anthologist

Of all the books I read this year (excluding those I’ve published) three stood out. I’ll start with the most famous one, and a book I didn’t expect to like at all—Orbital (Vintage) by Samantha Harvey. When the Booker longlist and shortlist were announced there were books I thought might prevail—although I hadn’t read any at the time, they seemed way more ambitious than the winner. Rachel Kushner’s Creation Lake and Percival Everett’s James (arguably the most reviewed and best-known literary novel of the year) were, to my mind, front-runners for the prize but there’s no accounting for the taste of prize juries. In the event, the moment I started reading Orbital I was hooked.

Nothing much happens in the book—it’s basically the story of six astronauts (belonging to Russia, Japan, America, Britain and Italy) in a spacecraft orbiting the earth. A routine mission where no dangers threaten. They’ll be in space for nine months, or as Roman, one of those on board, reflects, “Four thousand three hundred and twenty sunrises, four thousand three hundred and twenty sunsets. Almost one hundred and eight million miles travelled…In this new day, they’ll circle the earth sixteen times. They’ll see sixteen sunrises and sixteen sunsets, sixteen days and sixteen nights.” While there is much extraordinary beauty and drama to be observed from their perch high in space, the unspectacular daily routine could easily become a recipe for boredom. However, their isolation and unvarying days and nights help them introspect and feel keenly their bonds to earth, one another, and their distant families and that’s what this novel is about—a deep dive into the psyches of its characters. Enhancing our appreciation of the author’s skill in making us care for her characters is her exquisite prose. After I finished reading Orbital I could see why the Booker jury gave it the nod—this is a novel of huge literary accomplishment.

The next book on my list is, sadly, a book for our oppressive era—How Tyrants Fall: And How Nations Survive by Marcel Dirsus (John Murray). The author, an academic and political observer who has studied tyrants for over a decade, limits his argument to dictators and doesn’t look at strongmen at the helm of illiberal democracies. The book ranges broadly across time and geography. Dirsus examines the rise and fall of dictators in Europe, Africa, Asia, and throughout history. He writes well and marshals his arguments convincingly. For example, he shows us why dictators (with the exception of a few) lead an extremely precarious existence, despite their seeming invulnerability. He writes: “Tyranny is hazardous. According to a recent study that examined the way 2790 national rulers lost power, 1925 (69 per cent) were just fine after leaving office. ‘Only’ about 23 per cent of them were exiled, imprisoned or killed. But that was across all countries and political systems. Zoom in on personalist dictators— the leaders with the most power concentrated in their hands—and the numbers are reversed: 69 per cent of those tyrants are thrown into jail, forced to live their life abroad or killed.” The most interesting part of the book for me, apart from the author’s analysis of the psychological make-up of tyrants (which vary quite widely), is how he thinks they can be brought down. The way to topple a tyrant without creating a catastrophe, the author says, can be done, broadly speaking, in one of two ways: “chipping away at his pedestal to weaken it over time…or aiming to take out the tyrant more directly.” Using examples, he shows how each approach has succeeded or failed.

The last book on my list is the one I liked the most. The Golden Mole by Katherine Rundell (Faber & Faber) is the work of an incredibly talented writer. Rundell is a bestselling and much loved children’s writer but she is also a scholar who has written a much praised biography of John Donne, Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne, which won Britain’s prestigious Baillie Gifford Prize (she’s the youngest winner of the award).

Rundell first came to my attention when I read her glorious novel, Impossible Creatures (ostensibly for children but I enjoyed it thoroughly). The novel is largely set in an alternative world called The Archipelago, a group of enchanted islands. It is home to all manner of magical creatures—griffins, unicorns, man-eating horses called karkadanns, mermaids, al-mirages (hares with horns) and so on. This world is threatened by a great evil and the main characters of the book, Christopher and Mal, must save it. And save it they do. I was swept along by the plot and loved the world the author created. She is an exceptionally good children’s writer, fully the equal of Philip Pullman, Neil Gaiman and other contemporary greats.

The Golden Mole has no mythical creatures in it, these are birds and animals that inhabit our world, and that we are doing our best to kill off. The author describes 21 birds, mammals, and fishes, including the golden mole, of which there are twenty-one species, all living in sub-Saharan Africa and most teetering on the brink of extinction. This animal lives most of its life underground, emerging only to hunt for insects. So why are they called golden moles? Apparently, because they are the only mammals in the world that are iridescent: “Some species are black, some metallic silver or tawny yellow, but under different lights and from different angles, their fur shifts through turquoise, navy, purple, gold. Moles, then, with a tendency towards sky colours.” Other wondrous creatures that the author brings to vivid life include the Greenland Shark (“the planet’s oldest vertebrate…it’s very possible that there are in the water today sharks that are well into their sixth century”), the giraffe, the elephant, the wombat, the swift, the tuna, the spider, and the swift. Each animal, whether commonplace or rare, is described in such an ingenious and original way, that you realise that you are in the presence of an uncommonly gifted writer. Read her and rejoice.

Aatish Taseer, Author

Hiroshima: The Last Witnesses by MG Sheftall (EP Dutton) I was in Hiroshima last month and was haunted by it. The normalcy is chilling. It’s an impossible place to imagine, because, unlike the German concentration camps, it requires we subtract the life of a heartbreakingly normal town in order to imagine what happened here: the pika-don, or flash of intense light; the searing wind; the mortal cloud; human skin hanging like rags off people. On that Peace esplanade, the sounds of a bell ringing solemnly in the distance, I listened and read Sheftall’s powerful book. Next year is 80 years. As with Partition, living memory is fading away. This book captures the many surprising stories that intersected with the terrible events of that day. It also brings out an element about trauma that never ceases to amaze me and that is the shame of the victims—not just individual shame, but societal shame at the survival of the witness, which in Greek and Arabic alike, is etymologically inseparable from the idea of the martyr. He who lives to tell the tale must be punished.

My Friends by Hisham Matar (Viking) I have read (and loved) all of Matar’s books. This one touched me very deeply. It deals with exile. On one hand the arid, less romantic side. “It cannot be said they prospered here,” Matar writes of Arab writers in London, “If anything, they withered, grew old and tired. London was, in a way, where Arab writers came to die.” It is also full of a quiet melancholic love of London. I think this is what makes it almost a little provocative. Because when you think of our places—India, Africa, South America, great swathes of Asia—so few of them have lived up to the promise of those independence years, so few of them are places where anyone would want to live, even without the added horrors of environmental degradation. Exile is almost like a gravitational force today, drawing millions away from places that have failed them. Of course, it’s sad, of course it’s painful, but is there not some little part of us that is grateful to be away? In London, in New York. I felt this was the subversive undercurrent of Matar’s book. It is a celebration of liminality. Consider this description: “Even the shadows are allotted their places, and London is a city of shadows, a city made for shadows, for people like me who can be here a lifetime yet remain invisible as ghosts.”

My Beloved Life by Amitava Kumar (Aleph) What a triumph this book is! A capacious pastoral, with one of the most complex structures I have ever come across. Spokes of narrative, like shards of glass, reach out on all sides, creating a special kind of languid time that is akin to what time feels like within a life.

I have also never read a more loving description of rural and small town India. A ferry. A bus. A bridge. I found it deeply affecting—that inexorability of narrative outcome that only truly great novels have.

KR Meera, Author

Airplane Mode by Shahnaz Habib (Context) If an aviatrix is judged by her expertise in precision strikes, this book is like commando warfare, bombing our prides and prejudices. I have never come across a book like this, where wit, wisdom, and geopolitical insight converge, almost like a Sufi dancer whirling. It is, at once, a subversive history of travel, a collage of travelogues, backpack trips to the author’s inner landscapes, a pilgrimage to the cultural terrain of her origins, and a tour into the subaltern perspective of White Gaze and Third World.

Moreover, Shahnaz made me proud with the ‘magic-mushroom-like hybridity’ she has infused into Kerala and our collective Malayali memories. Phrases like ‘the ability to condense entire countries into crisp little sentences,’ ‘my Indian passport the throne to a kingdom,’ are just a few memorable ones.

Still, the most explosive of her insights are these: “To be a minority is to constantly orient yourself against the world.” “Migration and minorityhood are a more effective education in worldliness.” “Perhaps this is the underlying premise of luxury—to not see other people’s needs.”

Iru: The Remarkable Life of Irawati Karve by Urmilla Deshpande and Thiago Pinto Barbosa (Speaking Tiger)

This book captivated me with its Afterword, a conversation between its authors. Urmilla explains her reason for writing the biography of Irawati Karve, she wanted people, her family and friends, to know about their remarkable ancestor and how one woman’s decision to study abroad had such a lasting influence on an entire discipline — Anthropology. Thiago adds that it was shocking to see how many scientists could support racist and eugenic ideologies, writing about them with such scientific conviction. Many never realised that their science could have been wrong. So, to discover that one young Indian student, defying her German supervisor’s hypothesis, rejected the idea that there was a racial factor in skull shape and proposed that variations were due to environmental conditions was fascinating.

Reading Iru allows you to unlearn many misguided theories about the female brain and witness the power of a woman passionate about social sciences and humanity.

Gods, Guns and Missionaries: The Making of the Modern Hindu Identity by Manu S Pillai (Allen Lane)

It has always been a wonder why, after 300 years of Mughal rule and about 150 years of colonial rule, Hindus constituted 75 percent of India’s population at the time of independence. Either the conversion stories were exaggerated, or the claim of Hindu victimhood was false. Gods, Guns and Missionaries offers an explanation, which I found the most convincing, thanks to its extensive research — 49 per cent of the 859 pages are notes.

Pillai’s books delight me as a reader. He is an exceptional storyteller, brilliantly blending the past with the present, transforming history into a series of factually accurate tales, some stranger than fiction. Gods, Guns and Missionaries is distinct, provocative, and courageous, like his earlier works.

Manu S Pillai’s books delight me as a reader. Gods, Guns and Missionaries is distinct, provocative, and courageous, like his earlier works, says KR Meera

The book also references Kerala’s history. And contains harsh observations, such as, in Kerala, Narayana Guru rejected caste and social practices linked to Brahminical thought but not its philosophical content, indeed what divided Hindus from non-Hindus was untouchability not faith.

Speaking With Nature: The Origins of Indian Environmentalism by Ramachandra Guha (Fourth Estate)

As someone who has always spoken to nature and been spoken to by nature, the title caught my attention. Guha’s first book, focusing on the Chipko movement, inspired this one after he realised that thinkers like JC Kumarappa and Radhakamal Mukherjee had voiced the importance of environmental protection long before the Chipko movement. Tagore’s love for nature and his ideas on using modern science to rejuvenate villages are well known. It’s also illuminating to learn that Mukherjee, an economist turned sociologist, shared Tagore’s view that imperialism is a system of intensive resource extraction.

Ira Mukhoty, Author

You will understand something of the explosive depth of Irish writing talent when I tell you that 2024 was considered an under-achieving year for the Irish by Booker Prize longlist standards, with Wild Houses by Colin Barrett (Jonathan Cape) being the sole Irish entry. 2023’s list had fully four Irish writers, including the eventual winner of the prize, Paul Lynch with Prophet Song. For a country the size of a breadcrumb, this reckless excess of talent is breathtaking.

Colin Barrett displays all the trademark skills of Irish writers—a plastic facility for language, and an unerring instinct for the tightly told story. Indeed, the action in Wild Houses unfurls over the space of a single week-end in a small town in Ireland when two sketchy enforcers, the brothers Ferdia, kidnap and desultorily smack around a young man called Doll English to put pressure on his spineless local drug dealer brother.

Though this is a debut novel, Barrett is a decorated writer of short stories, and that incisive skill for the startlingly perfect description blazes through the book. One of the kidnappers, for example, has a face “like a vandalised church, long and angular and pitted…” while another character has arms so densely tattooed “they looked like the pages of a medieval manuscript.”

Though Wild Houses is a debut novel, Colin Barrett is a decorated writer of short stories, and that skill for the startlingly perfect description blazes through the book, says Ira Mukhoty

In an entirely different register is Orbital, by British writer Samantha Harvey (Vintage). The action here takes place over the course of a single day, as six astronauts on the International Space Station experience 16 sunrises and 16 sunsets as they orbit the earth. Orbital is a genre defying jewel of a book which Harvey herself has called “space pastoral”.

Harvey describes the planet as seen by the astronauts with immoderate love. It hums and shifts and changes like a live thing—warm air rises over the oceans and shapes itself into storm clouds, typhoons corkscrew over jewelled islands and the northern lights shimmer, sway and rise up against the endless black of space.

There are minute and heart-breaking revelations about life in space too. The tiny lab mice cling on to the walls of their cages, too terrified of zero gravity to let go, and must necessarily die at the end of the space flight. But the book is also and primarily a love poem to earth, which Harvey describes with sublime eloquence. The “planet sings with light as if from its core” and when the sun rises, it “spills its light like a pail upended and floods the earth…”

Harvey’s book had lain on my table for months until she won the Booker Prize for it in November, and I was then stung by my own procrastination. That meant that I ended up reading the book at the end of a catastrophic year—politically and ecologically. The impact of Orbital was therefore all the more immediate and urgent.

I cannot think of a more perfect elegy to the fragile beauty of our planet, and a more powerful call to set down arms, than this exquisite novel.

Manu S Pillai, Author

A book that left a mark is Santa Khurai’s The Yellow Sparrow, translated from Manipuri by Rubani Yumkhaibam. It is a straightforward, simple translation, but tells an important story—of queerness and a queer life rooted in Manipur as a region and culture. I found it instructive and deserving of wider attention, says Manu S Pillai

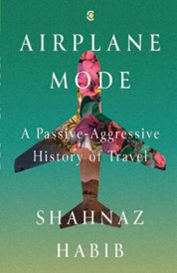

My booklist in 2024 has been rather heavy on nonfiction. One of the year’s most interesting reads was Janaki Bakhle’s Savarkar and the Making of Hindutva (Princeton University Press). Critically examining the ‘Father of Hindutva’, Bakhle marshals not just his well-analysed books but also his scattered Marathi journalism and poetry to better make sense of the man and his worldview. Mukund Padmanabhan’s The Great Flap of 1942 (Vintage) is a short, delightful microhistory, written with great charm and telling a little-known story—I learnt a good deal, and with many chuckles along the way. Another source of pure joy was Anusha Rao and Suhas Mahesh’s How to Love in Sanskrit (Harper Perennial)—a translation of Sanskrit poetry, full of beauty, humour, and occasional irreverence even. Many might imagine they ‘know’ what Sanskrit poetry is ‘like’; this book challenges such preconceptions. A book that left a mark is Santa Khurai’s The Yellow Sparrow (Speaking Tiger), translated from Manipuri by Rubani Yumkhaibam. It is a straightforward, simple translation, but tells an important story—of queerness and a queer life rooted in Manipur as a region and culture. I found it instructive and deserving of wider attention. Ira Mukhoty’s The Lion and the Lily (Aleph) marries her elegant writing with strong historical research, telling the story of Awadh, its nawabs and begums, and their dealings with a variety of Indian and European political players. It is a triumph and leaves one excited for Ira’s next project on the French in India. William Dalrymple’s The Golden Road (Bloomsbury), a history of the ‘Indosphere’ and its appeal in ancient times, must also feature here. A work of rich accomplishment, in many ways, it is unlike Dalrymple’s previous books. But he pulls it off with style. In terms of fiction, I have lagged this year. One entertaining read was Rohan Monteiro’s Shadows Rising (Westland), which draws inspiration from mythology to tell a fabulously fun story. I read the book in two sittings, and it offered much-needed reprieve from the dull, plodding work I was then engaged in. As my final recommendation, I will mention Srikar Raghavan’s study of the culture and intellectual and social history of modern Karnataka, Rama Bhima Soma (Westland). I read the book in manuscript form, and it will be in stores this month. Packed with insights—and at times a demanding read even—it is a solid debut.

Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, Poet

Away from the fanfare that greets the birth of a new book in India, Adil Jussawalla’s Body of Evidence in sickness and in health: Selected Prose (1966-2022) (Red River) came out. It is a collection of short essays that are in one way or another about the human body. Jussawalla’s prose has always had the lightness of a feather and been wide-ranging in its references. You never know on which bush his bird-like para will sit next. The mention of kari patta, in a review of cookbooks (Dharamjit Singh, Vimla Patil, Shalini Holkar), reminds him of tej patta whose aroma “has seen [him] through fits of depression in London”, restoring him to himself again. By this time, you know this is less a journalistic piece you’re reading and more a chapter in a great novel about a mind: Jussawalla’s.

Snehal Vadher’s Windows to a Mountain (Copper Coin) is his first collection. He writes in long (sometimes short) meditative lines, paying close attention to the world around him as well as to his response to it. Walking up a familiar route in Dharamsala where he lives, he approaches his destination. It’s a stream. “And suddenly,” he writes, “I’ve lost what I no longer need. / To be washed clean of a name / and then to go looking for it is fear.” Though these moments of vision can happen any time, they happen particularly on a “Sunday evening / [when] everything is preordained.” Sometimes the very ordinariness and predictability of the experience is the vision.

Jeet Thayil’s I’ll Have It Here (Fourth Estate), first new collection in 16 years, has political poems, elegies, love poems. He rhymes outrageously and walks a fine line between levity and seriousness. It has at least two unforgettable portraits. One of them, ‘Dinner with Rene Ricard’, is of a Manhattan actor, poet and art critic, who in the 1960s through the 1980s had one foot in the city’s low life, another in its studios and galleries. It’s the low life that brings them together: “He wanted no money, / had nothing to sell”. The second portrait is in ‘Save Your Brisé for a Better Day’. The woman is unnamed and shown surrounded with “acolytes”: “her face [a] springboard” from which they fell, stunned, yet, like “pilgrims”, came to worship at her shrine. They are in thrall of her beauty, her capriciousness, even as they see her rushing to her doom. It’s the last poem of the book, and not without a touch of divinity.

Saikat Mazumdar’s The Amateur (Bloomsbury) looks at writers from apartheid-era South Africa (Sindiwe Magona, Peter Abrahams, Es’kia Mphahlele), the Caribbean (CLR James, VS Naipaul) and India (Toru Dutt, Nirad C Chaudhuri, Pankaj Mishra), to see how they refashioned themselves even as, in different ways, they imbibed or deployed the colonial education they received. While Toru was taught by a private tutor, Magona was schooled under the Bantu Education Act. It would appear that Mazumdar’s engaging, finely written book disproves the point that we lack criticism that can be read for its own sake, but he proves it too. While he is an academic, he is also, importantly, a novelist and is a part of, and has a personal stake, in the world he writes about.

Anand’s The Notbook of Kabir is a Kabir DIY kit. Take it home with you, open the box, and make your own Kabir, says Arvind Krishna Mehrotra

Anand’s The Notbook of Kabir (Viking) is a Kabir DIY kit. Take it home with you, open the box, and make your own Kabir. It has everything you will need—except glue and scissors. That’s how Kabir songs work, and always have. Once you catch the rhythm (as you catch an infection), whatever enters your bloodstream and comes out of your mouth will not not be Kabir. To authenticate your song, turn to the Anandian Notes on Sources at the back. But you don’t need anyone to authenticate it either. Not a single original has ever been found, though the first recorded Kabir song is perhaps in a Buddhist text and was sung by a woman 2,700 years ago.

Sonam Ahuja Kapoor, Actor

Percival Everett’s James (Mantle) is very clever and thought provoking. It’s subtly written but it is layered with meaning and that’s the kind of literature I enjoy. He also has a way of challenging conventional thinking and in James, he does that, right? He weaves humour, intellect and humanity in a really cool way. And I think the book has stayed with me for a long time after I read it, and I thought that was brilliant.

Konkona Sen Sharma, Actor and filmmaker

I finally finished Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl by Andrea Lawlor (Pan Macmillan) on a whirlwind family holiday across the oceans, late night on a hotel room bed, reading with my son. These are all favourite things. Thank you to my friends for gifting me this coolest of all books, for taking the chance that I would love it and would long to find myself in Paul—‘an antihero for the ages’. I’m also currently reading and loving The Day I Became a Runner by Sohini Chattopadhyay (Fourth Estate). My Husband by Maud Ventura (translated by Emma Ramadan, Penguin), should be read on flight, as is best for deep reading. Especially when it’s a cracker one-day-read like this one. A tense and delicious reminder of the horrors that monogamous domesticity can easily lead itself to.

Saif Ali Khan, Actor

Pandora’s Jar: Women in Greek Myths by Natalie Haynes (Picador) is a wonderful collection of essays on these very famous female characters in Greek myths who have often been sidelined or treated a certain way, probably because of the patriarchy, and that way of looking of things. But if analysed a little more closely, or even if earlier sources writing about these women are taken into consideration, then their true character emerges and how they were incredibly strong and have usually been wronged by the male gaze and I thought that was interesting and it’s also really well written and I love mythology.

Amit Chaudhuri, Author

Bride in the Hills, Vanamala Viswanatha’s joyous translation of Kuvempu’s 1967 novel, Malegalalli Madumagalu, came out this year in India from Penguin Modern Classics. This is something of an event, and, in another time and culture, would be an occasion for a serious reengagement in the sort of literary periodical we don’t have in English in this country. The length of this 760-page novel (which is set in the late nineteenth to the early twentieth centuries) encourages comparisons with nineteenth-century realist fiction (Tolstoy’s name comes up) and epic narrative, but the novel’s chief preoccupation is neither character nor panorama (though it captures these with energy) nor even story—it is to embrace the present moment through remarkable shifts in focus and attention in the first two hundred or so pages. However difficult the lives it evokes in a predominantly non-upper-caste world, it cherishes, through comedy and poetry, life’s often inexplicable abundance.

New York Review Books published Benjamin Swett’s The Picture Not Taken: On Life and Photography this year. Swett is a photographer and writer, and has now composed this meditation on pictures taken by his father, an amateur photographer who used to work in New York as a reporter in the 1970s. The photos his father took of family and of New York (Coney Island, say) and of political unrest are partly a record of an impulse that has grown obscure over time, while the pictures have become, at once, more moving and enigmatic. Swett’s mesmerising text is a reminder that there are many ways of making art, and one of them is to read. This is what his looking at, and reconsideration of, these photographs really is—an act of reading, and, through reading, to create meaning.

The mesmerising text in The Picture Not Taken is a reminder that there are many ways of making art, and one of them is to read, says Amit Chaudhuri

Philosopher and critic Michel Chaouli has been engaged for some years now with fashioning a response to the literary; he calls it, after Schlegel, ‘poetic critique’. The term, I think, is meant, on the one hand, to acknowledge the impasse at which academic writing in literature departments finds itself; and, on the other, to breathe new life into criticism. This, in effect, is what his book Something Speaks to Me (University of Chicago Press) sets out doing. It begins: “I want to tell you about a mishap I had while teaching Franz Kafka’s novel The Trial a few years ago. The basics are quickly summarized: after reading out loud a passage that I had chosen because it seemed especially rich, I found I had nothing to say about it. Nothing.”

The book considers the questions arising from this momentary inadequacy with imagination and a probing, enthralling obstinacy.

/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Cover_Double-Issue-Spl.jpg)

More Columns

The Heart Has No Shape the Hands Can’t Take Sharanya Manivannan

Beware the Digital Arrest Madhavankutty Pillai

The Music of Our Lives Kaveree Bamzai