Books | Best of Books 2024: Nonfiction

Perpetrators, Victims, Bystanders

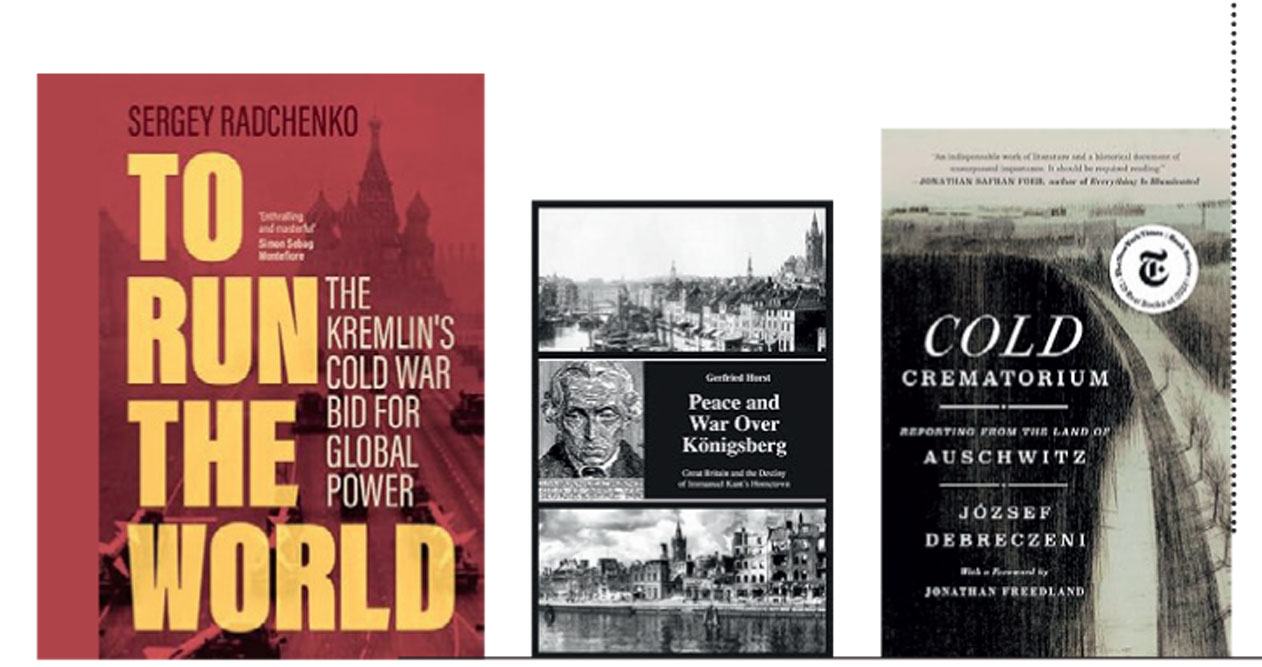

József Debreczeni | Gerfried Horst | Sergey Radchenko

Sudeep Paul

Sudeep Paul

Sudeep Paul

13 Dec, 2024

Sudeep Paul

13 Dec, 2024

József Debreczeni, a Hungarian Jew from Yugoslavia, was deported to Auschwitz with his wife and parents in the spring of 1944. He survived through a succession of forced labour camps, weakening in health and ending up at Dörnhau, doubling as a ward for the dying. Dörnhau is the ‘cold crematorium’ in Cold Crematorium: Reporting from the Land of Auschwitz (St Martin’s Press, translated by Paul Olchváry), a Holocaust memoir on a par with Primo Levi and Elie Wiesel but uniquely objective. Debreczeni, a journalist, sees himself from the outside, dispassionately, as he describes what man does to man. “My name was Farkas. Dr. Farkas,” says a fellow prisoner (emphasis added). Debreczeni was just the number 33031. The book was published in Yugoslavia in Hungarian in 1950 and then lost to humanity. Soviet Bloc regimes, with their undisguised anti-Semitism, were not happy. McCarthyism, in a way, didn’t let it cross the Atlantic. Translated last year, it came out in January 2024, 79 years after the liberation of Auschwitz, 80 since Debreczeni arrived there, thinking “Surely I couldn’t end up in a place much worse… how tragically wrong I was.” There’s always someplace worse, ad absurdum. “Language is the only homeland,” said Czeslaw Milosz. It is only language that preserves body and memory. In the process of being translated to more than a dozen languages now, Debreczeni’s memoir will add significantly to Holocaust literature, proving once more that ‘poetry’ was still possible after Auschwitz, albeit of a different order.

“Death is a master from Germany,” wrote Paul Celan. But what do we make of ordinary Germans—arch bystanders when not perpetrators—claiming they were the Nazis’ first victims? WG Sebald, in On the Natural History of Destruction, observed how Germans went about their business post-war not noticing, or pretending not to notice, the devastation of their cities around. They were incapable of introspection. But then there were also the refugees from the Red Army’s advance, from the legitimate eastern lands Germany lost. The morality of the destruction, rather erasure, of Königsberg, Immanuel Kant’s city, once called the captial of philosophy where Prussian monarchs would be ceremonially crowned, is less complicated. Königsberg, with its medieval English (and Scottish) mercantile and migrant connections, was annihilated by British bombs in keeping with “Bomber” Harris’ area-bombing strategy. The ruins were demolished by the Soviets, the residual population expelled, and an alien Kaliningrad erected on top. Gerfried Horst’s Peace and War over Königsberg: Great Britain and the Destiny of Immanuel Kant’s Hometown (independently published) invokes more than the ghost of Kant, bringing alive a city lost to time 80 years ago and raising immediate questions connected to both the Ukraine war and the Middle East conflict.

British-Russian historian Sergey Radchenko’s To Run the World: The Kremlin’s Cold War Bid for Global Power (Cambridge University Press) will become an important work of Cold War historiography. The Cold War was always a “three-body problem”. Unfortunately, most of the older histories dealt with the two superpowers while ignoring China. And looking only at smaller, third-world players, as scholars and analysts tend to these days, merely inverts the pyramid. Radchenko accesses Soviet and Chinese sources not available earlier. The product is expansive in scope, from Stalin to Gorbachev, and penetrates the psychology of Kremlin decision-making. Was Moscow trying to run the world or lead the revolution? This dichotomy, and obsession, characterised Soviet thought and action through its post-war existence. At times, it didn’t seem confident of itself . At others, too eager to shake up the world order. It ended up blinding the Kremlin to how bad things were even before Gorbachev’s reforms and his refusal to crush the revolutions in East Europe with force. The Soviet Union died without understanding itself.

More Columns

The Heart Has No Shape the Hands Can’t Take Sharanya Manivannan

Beware the Digital Arrest Madhavankutty Pillai

The Music of Our Lives Kaveree Bamzai