In Memory of the Three Million

A national monument to the victims of the 1943 Bengal Famine can enshrine cooperative federalism

Kishan S Rana

Kishan S Rana

Kishan S Rana

Kishan S Rana

Kanchan Nagpal

Kanchan Nagpal

|

09 Aug, 2024

|

09 Aug, 2024

/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Inmemoryof3million1.jpg)

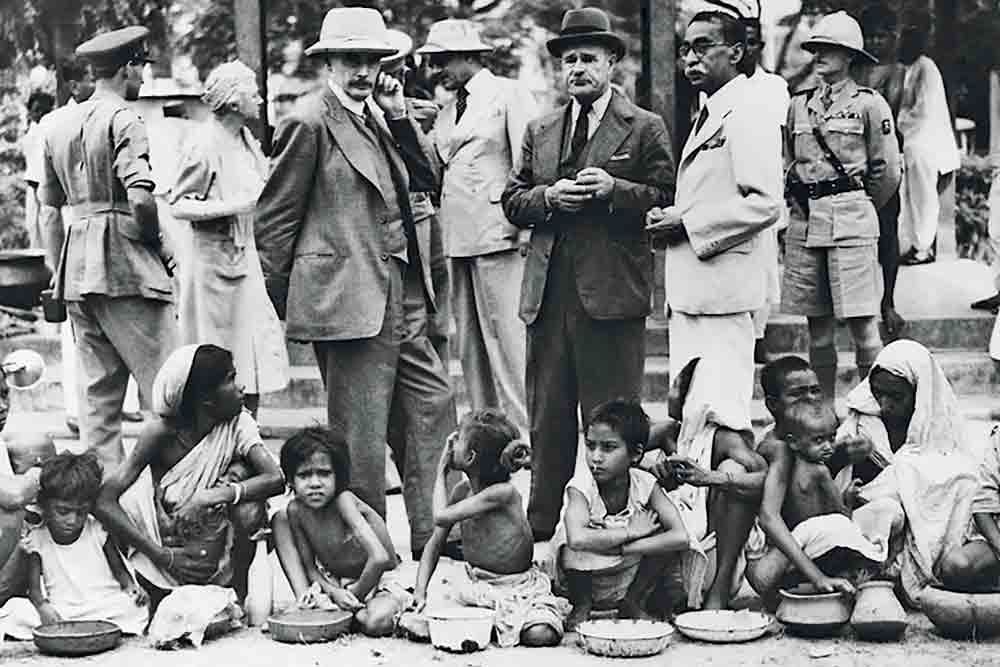

A child begging for food in Calcutta during the Bengal famine of 1943 (Photo: Getty Images)

In the middle of Second World War, in the dying days of Empire at least 3 million Indians, British subjects, died in the Bengal famine. Three million. It’s one of the largest losses of civilian life on this side. There is no memorial to them anywhere in the world, not even a plaque. How do 3 million people just disappear? …I spent the last year scouring archives and tracking down eye-witnesses… One said: “People were walking around, saying: Please Mother, give us some rice water.” Because they were so desperate. I had nightmares over some of the things that happened”…I searched for the last remaining survivors… Another said: “They were hiding in plain sight, in villages all across West Bengal and Bangladesh…(they) are the part of our history that we feel unable or afraid to address… there is no voice for the 3 million people…

—Kavita Puri, Three Million, BBC radio series, February 2024

N 1942-44 EAST INDIA UNDERWENT THE greatest human tragedy of Britain’s imperial rule. It is also the least examined major event since the 1757 Battle of Plassey. Both these occurred in Bengal, then India’s political hub, the pivot in British conquest, when they overcame their final obstacles, the Indian princes and the rival European powers, all thirsting for India’s wealth. This is an examination of that Famine, the tragedy that India forgot.

The calamity was the consequence of four clusters of trigger events: first, rainfall in eastern India was deficient in 1942; a cyclone over Bengal in September inflicted major agricultural losses. In the subcontinent’s monsoons, bad years follow good ones. Second, Japan’s December 6 surprise attack on Pearl Harbour crippled US sea-power in the Pacific for over a year. Central to its war strategy, Japan launched a massive invasion of Southeast Asia. With ship-borne troops, warships and aircraft, it struck deep. In five months of shock warfare, Japan swiftly seized Malaysia, Singapore, and lower Burma. Thailand quickly worked out a deal with Tokyo, restoring a façade of autonomy. British forces and their colonial and other local troop formations collapsed. ‘Unsinkable’ battleships, the Prince of Wales and Repulse sank in two days of battle; Britain had not anticipated Japan’s land-based bombers, or carrier-borne aircraft carrying torpedoes and bombs. Third, normal rice imports, from Burma into Bengal ended, aggravating shortages, prompting hoarding. Food prices surged. Four, British India went into shock, producing an over-reaction. New Delhi gave British military forces a free hand over the civilian administration. That produced chaos.

Japan’s onslaught created panic in East and South India, an overwhelming fear that they were the next targets. The fall of Singapore was especially traumatic. East India adjoined Burma; Bengal saw itself as Japan’s next juicy target. A recent book captures well that febrile mood, the panic exodus of officials and others, from East and South India. That rare study is based on documents from subordinate units, municipalities, and the local administration; such ‘subaltern history’ is not an Indian forte. (The Great Flap of 1942: How the Raj Panicked over a Japanese Non-Invasion by Mukund Padmanabhan, 2024).

That produced huge consequences for rural Bengal. British troops (not the British Indian Army) implemented a ‘DENIAL Policy’, that is, scorched earth. That Army was ignorant, unmindful of the local village ethos, understood nothing of poor farmer households. Overruling the local administration, they seized household rice stocks, dumping in rivers or burning the small reserves. They cared little for the sustenance of small farmers, one crop to the next. Their orders: invading Japanese troops must not seize this food. No one asked: Was it feasible for a Japanese invasion to reach and invest Bengal? In reality, Japan ran out of steam by mid-1942, with overstretched supply lines. Japan was later to make its last throw of the dice, a fanatical, futile attack on Imphal in Northeast India in March-July 1944.

World War II short-circuited British Indian thinking, producing hasty, self-contradictory, disastrous responses. Further, the inexperienced, fractious provincial government of the Muslim League clashed with the Bengal governor and his officials, adding to the confusion. For example, Bengal’s timid rural famine relief work ran up against a land revenue collection drive by another branch of that same administration. Could farmers facing starvation find money to pay land revenue? (Through War and Famine: Bengal 1939-45 by Srimanjari, 2009).

LONDON’S INDIFFERENCE

An abundance of historical documents, including War Cabinet papers, the daily diary of Secretary of State for India Leo Amery, and memoirs, detail a different kind of ‘denial’. Viceroy Linlithgow’s frantic pleas for additional ships to bring foodgrains donated by Australia and then Canada fell on London’s deaf ears. Commanding global shipping allocations, they refused extra shipping. A singularly incompetent Linlithgow and his New Delhi cohort persisted in their futile refrain; they also refused to re-assign ships from their regular quota for foodgrains (Churchill and India by Kishan S Rana, 2022).

From the outset, British India had imposed a news blackout on the famine, so that Japan and Germany might not make propaganda capital from the calamity. Especially sensitive: any mention of the famine in two-way family communications with Indian troops, who by 1942 numbered 1.5 million. But of course, such news could not be kept bottled-up (BBC).

Inter-province movements of foodgrains were stopped to prevent transfers from Bengal to other provinces, as was customary; Bengal normally produced a surplus. Ian Stevens, editor of the largest circulation Indian newspaper, The Statesman, reported on the famine in August 1943 defying censorship; the paper also carried famine photos, arguing that censorship did not apply to that genre. Soon the famine was out in the open (BBC). In London, parliament discussed the famine for the first time in August 1943. But the famine was never officially declared, which was essential for full statutory relief measures to take force.

The British troops seized household rice stock. They cared little for the sustenance of small farmers, one crop to the next. Their orders: invading Japanese troops must not seize this food. No one asked: Was it feasible for a Japanese invasion to reach and invest Bengal?

Amery’s well-documented internal battles with Churchill were unique; former fellow students at Harrow (Amery was senior by three years), they were ‘frenemies’ in today’s idiom, but that is another story. On August 4, 1943, Amery urged the War Cabinet to consider the seriousness of the “(British) Indian demand for 500,000 tons… the Cabinet treated the matter as a bluff on India’s part” (The Leo Amery Diaries, August 4, 1943).

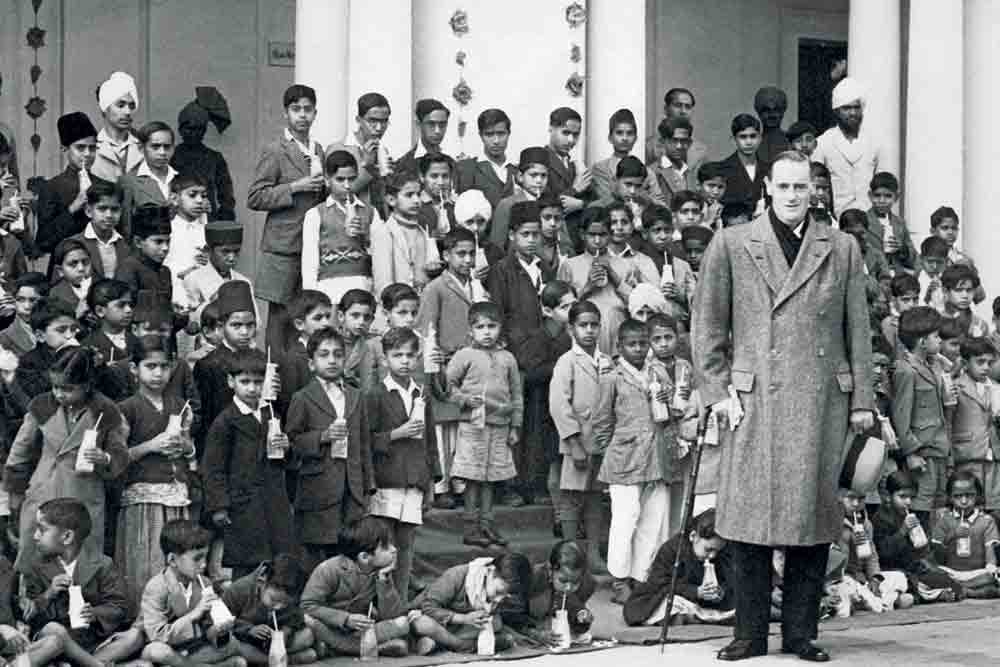

Archibald Wavell took over as viceroy in October 1943, and one of his first acts was to visit Bengal. Relief measures were reinforced; for the first time, the Army was deployed for this purpose. Good rains in late 1943 meant that the tide would turn when that crop came in. But it was too late for the ‘Three Million’.

On January 20, 1944, Amery told parliament that perhaps a million may have died from the famine. He recorded: this “made no stir”. As late as March 13, 1944: “The Cabinet still refuses to do anything about wheat for India”. Viceroy Wavell was to record in his diary: the Churchill government’s attitude to India was “negligent, contemptuous and hostile”

(Bengal and Its Partition by Bhaswati Mukherjee, 2021).

WOODHEAD COMMISSION, 1944-45

British India appointed the Woodhead Commission in 1944-45, headed by an official of that name. Commission members were not allowed to record personal notes on the proceedings. Hindu and Muslim communities had a member each; Sir Manilal Nanavati’s notes, written in defiance of the restrictions, are in New Delhi’s National Archives. This commission could not address the truth, so they argued, and spun wheels. The report, published in 1945, was a whitewash. How could British officials tell the truth, when ‘EXIT’ signs were flashing?

Amartya Sen (Poverty and Famines, 1981) shows incisively that in 1943 people died in front of well-stocked food shops which were protected by the state. The poor simply lacked the means to buy food. Rice, the staple, was available; the poorest did not have the means to buy it. It was a crisis of distribution. Remember, their small personal reserves had been destroyed by the Sarkar’s Army.

Why did this happen? BBC explains comprehensively (paraphrased): First, an elaborate ‘Famine Code’ dating to the late-19th century applied. An official says “we did not know what to do” (a 40-year-old recording). Second, that Code stipulated ‘Test Works’; one had to work to get payment to buy food. The famine-ravaged were too weak to work; ergo, no payment. This ‘Catch-22’ method dated to Britain’s old charity works laws. Third, the same official said: final decisions were taken by the ‘military command’ (not the provincial administration); their priority: confronting a Japanese attack. In fact, Famine was never declared.

RAVAGES AND AFTERMATH

The famine’s principal victims were the poorest in the rural areas. BBC captures not just the grief, but the shame of survivors. Those reduced to skeletons had made the harshest choices; who might get the last morsels of rice or any eatable. Women, pre-teen girls, went with men who could feed them (BBC). Sailen Sarkar, speaking of his interviews, said: “I was very emotional… Some people were 90 or older, even 100… I burst into tears with them.” (at IIC, June 21, 2024). “Why did we live?” they asked. Another survivor asked Sarkar: “Why did you come so late?” on hearing Sarkar wanted to record his testimony. One admitted: “Even our families have not asked about our suffering.” Another, from a better-off rural family confessed: My family purchased land at cheap prices; in one family, everyone had died “so we took the land” (BBC). This goes beyond the speakable.

In Kolkata and the other urban centres, a different kind of anguish and embarrassment emerged. The knowledge that they could do so little for their rural brethren. They too had to survive. Amartya Sen told BBC: As a young boy living with his grandparents in Santiniketan, when the starving came to the front door, his family had allowed him to give them rice, but limited to what could be contained in a 50-pack cigarette tin. Some families gave gruel to those that came to their gates seeking food (Krishna Jhala). People just did not have the wherewithal to do more. That haunted them.

Is this why there is no demand, or even discussion, in the former province of Bengal, about a memorial to the famine victims, even in the early years of independence? Perhaps a kind of ‘survivors’ guilt’, collective embarrassment?

THE INDIAN RESPONSE

Most leaders of India’s independence movement were in jail, held from August 1942 onwards, immediately following the abortive (ill-advised?) Quit India Movement. Gandhiji was released in May 1944; Nehru and other Congress leaders in April 1945. “Jinnah had a field day in consolidating his hold over the Muslim majority provinces.” (Ishtiaq Ahmed). He consolidated links with Churchill, and with the British India administration, and through that built up support for himself, overtaking other important Muslim leaders (Rana).

Gandhiji was in jail till May 1944; the famine ended, although rice shortages persisted a little longer. His comment at that point could not change what had already happened. As ever, he was more reflective and ‘value-driven’ than others in the Congress leadership. It was not his style to directly criticise British actions. After all, since 1923, he had responded to Churchill’s inventive, nasty, racist insults with wry humour and gentle repartee.

Jawaharlal Nehru: “The Bengal famine is not a result of scarcity but of gross mismanagement and exploitation by the British government, which prioritized war needs over the lives of Indian people.” (Comment dated 1943, A Discovery of India, 1946). “Millions of our people are dying because of the inefficiency and callousness of the British administration. The famine in Bengal is a direct consequence of their policies.” (1943), (1937-1940, Collected Writings, 1948).

Subhas Chandra Bose: “The Bengal famine is a result of deliberate neglect and cruel policies by the British government who have shown no concern for the starving millions.” (Azad Hind Radio, August 1943).

Jinnah told the Central Legislative Assembly on November 18, 1944, that control over India was with the British who bore the blame for the famine; he also defended the Bengal Provincial Government (Ahmed).

In Bengal there were different voices. Eminent Bengali BC Roy urged that relief be entrusted to voluntary organisations. (Srimanjari).

RECENT STUDIES

Two books emerged in 2010. Srimanjari wrote Through War and Famine: “(In) Jyotirmoyee Devi’s short story ‘Neel Chokhe’ (1943)… the Sikh soldier laments the absence of rage among the famine victims of Bengal. The British soldier concurs… a similar situation would have catapulted into a rebellion in Britain and the Bengali clerk relates the lack of a rebellious spirit among Bengalis to political bondage… (this) draws attention to the devastating impact of imperialism, World War II and the famine of 1943”.

Madhusree Mukerjee wrote Churchill’s Secret War. The product of extensive investigation, including archives examined for the first time, it argued that Churchill precipitated and aggravated the calamity. His egregious, damaging decision was the denial of adequate relief at the famine’s worst, late 1942-43, though both ships and grain were available. He chose to stockpile grain for Britain’s use, after the war. Mukerjee was attacked viciously by Western historians; some said she was not “a professional historian”.

Another book, Janam Mukherjee’s Hungry Bengal (2015) seethes with fine detail. His father, before moving to the US, had lived the famine. Visiting India in 1999, Janam learnt Bangla, interviewed survivors, scoured city archives, harvesting new details. For example, in the 1941 panic, of 66,000 sea-fishing ‘country boats’, minimally mechanised, 46,000 were seized, with scanty compensation, ruining the livelihoods of hundreds of thousands. He consigns responsibility beyond Britain, listing Indian politicians, mostly local; he also speaks of the dehumanising of survivors.

Bhaswati Mukherjee’s Bengal and its Partition (2021) has a chapter on the famine. She called it one of the most tragic and unwritten genocides of human history; it was a manmade calamity. That lack of pity or compassion would violate today’s international human rights standards.

OUR AMNESIA

As a people we have ignored the century’s largest human tragedy. World War II, its exigencies and bad judgements contributed to the famine. A few years later came Independence and the trauma of Partition. The Bengal of British India, a major locus of massive, bloody Hindu-Muslim riots, became East Pakistan and West Bengal. The urgent imperatives of self-rule were to restore order in Bengal and Punjab, and take charge of the entire governance machinery of the two new countries. Did we as Indians simply overlook the famine, or decide to let the past fade away, both in New Delhi and in the east?

INDEPENDENCE AND AFTER

Churchill’s racism, his hatred for India and Hindus, and his mismanagement of the subcontinent from May 1940 to August 1945 as British prime minister were gross lapses. Responding to the famine, he said repeatedly: “The Bengalis are half-starved anyway.” In 1953, he went on to win a Nobel for literature; the citation praised his “humane qualities” (Rana). British historian Max Hastings told BBC that he remains “a deep admirer of Churchill”; he added: Churchill “saw Indians as a sub-species… this is a very large blot on his reputation” (Three Million). That Churchill was a towering, inspirational leader during WWII is beyond question. Does that give him a free pass: that his egregious lapses must be accepted in silence?

After August 15, 1947, the Indian government chose open cooperation with the former imperial power. No political movement, or region in the country, or organisation, demurred in public. The famine was forgotten, gently remembered mainly in Bengal.

No one else has done anything comparable to BBC’s oeuvre, with firsthand testimonies. It is moving, beyond words. We owe much to Kavita Puri and that team for bravely tackling the famine.

LOOKING AHEAD

In 77 years since Independence, Union governments of different hues have come and gone, as have state governments. Bengal has enshrined the famine martyrs in drama, novels, poetry, and storytelling. And the indefatigable Sailen Sarkar, his Gangchil cohort, and their ilk have collected documents, drawings, interviews, photos. Mostly unnoticed.

We cannot remain supine. A thought: Can we establish a world-class agriculture research institution of excellence, not in Kolkata, but in a rural West Bengal area where the famine had struck hard? Naturally, the infrastructure created would include a national memorial to the ‘Three Million’. It should be conceived as a forward-looking action. It should enshrine cooperative federalism.

Further, we should build the project with voluntary contributions from individuals and entities, within and outside India. We might be surprised by the response. The cause is evocative and worthy.

This entails cooperation between the Union government and the government of West Bengal, ruled by different parties and political clusters. Is it feasible? We will not know until we make a real effort. Let us do this for those martyred in the famine.

/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Cover_Double-Issue-Spl.jpg)

More Columns

The Music of Our Lives Kaveree Bamzai

Love and Longing Nandini Nair

An assault in Parliament Rajeev Deshpande