LOVE AT FIRST FIGHT

Our contributor and actor DIVYA UNNY has found the best exercise for her body and mind: the ancient martial art form kalaripayattu. She is not alone

Divya Unny

Divya Unny

Divya Unny

Divya Unny

|

09 Apr, 2015

|

09 Apr, 2015

/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/18286.loveatfirst1.jpg)

Gyms were too cold. Yoga was too slow. Going for a jog required too much discipline, and a swim was too expensive in Mumbai. For years, I was ready with an excuse when it came to pushing my body—partly because I’m blessed with the metabolism of a new-born and partly because I never really craved a regular workout. With the lifestyle a city like Mumbai offers, you spend half your time swinging out of local trains, and the other half, working towards never having to take such trains again. As a result, your body is more or less warmed up most of the time. Plus, the secret motto of my subconscious was: ‘You are thin, why not wait until that extra layer of fat accumulates, if it does?’

All that changed towards the end of last September when I dunked myself into a 21-foot deep kuzhi kalari (underground mud pit) built on the edges of Adishakti Theatre camp near Auroville, about two hours from Chennai. To the smell of incense and the chill of wet earth, we, 20 young artists from various cities, attempted to accomplish the initial few moves of India’s oldest martial art form. We were being introduced to kalaripayattu as the first step of our actor’s training workshop. Most of us were from a space where martial arts were part of pop culture (read Jackie Chan, and in my case, Mammootty) than real life. As a Keralite, the state where kalaripayattu originated, for me it was about flying bodies, the clinking of metal arms and thoroughly choreographed combat moves that could only be mastered by training from a very young age. To pursue it in everyday life seemed far-fetched. That was among many other perceptions about to be shattered over the next 11 days.

Our mornings would begin at 7 am in the kalari that was dotted with deities in each corner. If legend is to be believed, we were training in a 3,000-year-old spot that had hosted some of the greatest warriors of all time. The energy within the mud pit engulfed and cocooned us from the outside world for that one hour. “Kalaripayattu was always taught in isolation, away from the prying eyes of the enemy. It prepares you to combat the brutalities in the real world,” said our master Vinodji when we asked him about the significance of the closed space. With the flicker of the flame shining in front of the deities, we warmed up. We began learning the vadakkan (northern style of kalaripayattu) by paying salutations to a seven-tier platform symbolising the seven stages of the art form.

Some of us were classical dancers, others had dabbled in tai chi and taekwondo, and a few owed their flexiblity to gym equipment. But as we began with the kalari moves, our bodies surprised us. In a half sitting position for almost a minute, I was losing sense of my shin. My torso was parallel to the earth and arms extended straight following my eye line. Sweat that began accumulating on my forehead was now making the ground around me moist. “Focus on one point,” is what I thought I heard Vinodji say. As a Bharatanatyam dancer, my body was used to gravitating towards the ground, but kalaripayattu demands that you be as close to the earth as possible. It was challenging, and we had to find a motivation we did not know we had within us.

The crouches, the leaps, the kicks, every thump of the leg, every cross-split, every scissor cut we attempted drew inspiration from the raw power and sinuous strength of animals; moves graciously borrowed from the lion, the tiger, the snake, the elephant, even the cock. The first few days were pain-ridden, but the key was to keep focus. What amazed me was that after an intense hour of class, I’d never feel out of energy. Instead, I felt a source of strength unleashing itself at the navel point. It empowered me like no other physical activity had. For the first time in 30 years, my body craved being wrung in ways it didn’t know it could be.

“The form is so organic that it brings you closer to nature. You draw energy from the earth. It makes you agile, and once you really discover it, it’s a different kind of high,” says Nimmy Raphael, 32, the actor who coached us after our kalaripayattu sessions.

Those 11 days had started something, and it was a fight I knew I couldn’t leave half way. Once I was back in Mumbai, I immediately enrolled myself for classes.

The classes were conducted by Belraj Soni, kalaripayattu instructor at Mumbai’s Somaiya College and founder-director of Navaneetham Cultural Trust, Thrissur, Kerala. He had been teaching the art form for over 20 years. The sprawling sports ground at IIT Mumbai, where it was conducted, was however far removed from the quiet mud pit I had crawled out of in Auroville. There were students playing basketball on one side, hockey on the other, and right in the middle were 30 of us, kalari beginners, bare feet, with our bodies the only instrument to work with. Distractions were aplenty, and hence the challenge to combat them.

Young and old, people from various walks of life diligently followed the Malayalam instructions the moves were coupled with. “Edathu neere, valathu neere, edathu neere, valathu neere,” Belraj Sir would say, instructing us to kick our legs one-by-one high up in the air and back. We trembled, limped, sometimes even cried our way through class, but did not give up. We performed in track pants instead of the traditional half dhoti, but the appeal of kalari went beyond its costumes. “Eight years ago, when I started practising it in Mumbai, barely two students were actively involved. Now, due to the overwhelming response, I am forced to limit the seats on a first- come-first-served basis,” says Belraj, who has trained over 600 students from Mumbai so far.

Of late, the art form has found resonance with urban folk irrespective of age or gender. Like 17-year-old Poorvi Bellur and her mother, 45-year-old Sumana Srinivasan, who started learning it together a month ago. “I have a really stressful schedule because of my 12th grade boards. So there’s a different kind of satisfaction coming out here and letting yourself get physically beaten up. You feel like you have done some substantial work, which you don’t after six hours of studying,” says Poorvi, who has also been a classical dancer for 12 years. “The aggression of martial arts wasn’t something I really saw myself doing. As a dancer, my physical exercise has always been paired with some amount of aesthetic appeal. But that perception of kalari being aggressive has completely evaporated.”

Sumana is a patient of rheumatoid arthritis. “I was always told by doctors to keep my body active. Yoga and a few other forms helped, but I was always curious about kalari,” she says, “I was most concerned about my knees and elbows, as they don’t have a complete range of motion. But with kalari, when I started doing the squats, my quads got very strong. My knee and shoulder pain has considerably reduced and I haven’t had the need to take painkillers ever since I started learning it.”

I discovered that kalari in Mumbai was finding students in ad executives to housewives to PhD candidates. “I could barely climb two flights of stairs before I started practising kalaripayattu. It’s the kind of workout that works on your body and your mind. I feel way calmer and better equipped to deal with the kind of rushed lifestyle I lead,” says Priya Anchan, a 30-year-old brand manager at Lowe Lintas who has been training for over a year now. “My mother thinks I’ll build muscles and no one might marry me because of this,” she adds with a smile, “but that’s a misconception.”

Purists may express dissent over the art form being perceived primarily as another method of exercise, but there is no dispute about its rising popularity. “It is good that awareness is increasing. Other forms of martial arts, gymming or aerobics concentrate on improvement and strengthening of one’s physique, but it doesn’t work your mind. Kalari aims at the balanced growth of both. The training is more acute and time consuming. It cannot be treated as a hobby,” says Belraj.

As an actor, there are few tools that have helped me hold my own on stage as much as kalari. During performances, I am more aware of my body and consequently more in control of it. There is a sense of calm that has replaced the incessant nervous energy that would often rule me on stage.

Kalari has always been used as a form of self-expression. But I am now able to identify the train of thought behind a series of contemporary works that have used the art form to communicate their stories. I am particularly intrigued by the Bengali play Tomar Dake, conceptualised by Theatre Shine, a group of under 25-year-olds from Kolkata. The play is a visually striking portrayal of social injustice and violence, where kalari motifs are glaringly used to symbolise growing anarchy. Says its director Suvojit Bhandopadhyay, “We specialise in psychophysics threatre, and the history of the art form worked for us. We trained in kalari for about four months before applying it to text. We used the kalari pranam to symbolise a new ruling power emerging within states. The attack and defence modes in kalari became a strong and aesthetic tool for us to portray social violence.”

For others, like the artists from the Adishakti Theatre group, founded by the late Veenapani Chawla, kalaripayattu is a way of life. So too for Nimmy Raphael, popular for reprising the mythological figures Laxmana and Kumbakarna in her play Nidrawathwam. “I’m a performer who doesn’t feel gender on stage,” she says, “I don’t have a very feminine body, neither do I feel very masculine. Kalari helped me with my journey in being able to transcend gender on stage. Whatever movement you do, it forces you to find something. It trains you psychologically as an actor, it lays down the basics of your movements.”

Be it the Attakalari Centre for Movement Arts in Bangalore or National School of Drama (NSD) in Delhi, kalari is being used by institutions to add aesthetic and emotional appeal to works of art. This includes a recent play called Zubaan, where I perform a series of monologues to promote gender sensitisation. The play, which also has Tom Alter, requires me to act out an attack sequence as a rape victim, and to my surprise while choreographing my moves, I found myself using several kalari stances. The role, which began as a disturbing experience for me, has transformed into one where I feel better equipped to fight the perpetrator.

That was perhaps also the reason for my response when my learning was recently put to test in real life. It happened one evening about five months into my kalari training. I was riding in an autorickshaw to the IIT ground. A minor dispute with the auto driver turned into a fight that had the burly man grab me by the collar, threatening to slap me right across the face. He was twice my size. But something within me nipped my fear. I did not attack him, but I found the strength to undo myself from his hold and turn him over to the police. I missed class by 45 minutes that day. “You should have done the ashwa vadivu on him,” one of my kalari girlfriends told me. It was the day I realised I have a long way to go.

The martial art form helps centre the mind, keep the body in shape, and for urban women living in an increasingly turbulent environment, it is an ideal tool for self-defence. “My confidence levels have increased a lot,” says Dilna Shreedhar, a 26-year-old PhD student, “The way I sit, carry myself, my personality, my walk, everything has changed. I am short and small of frame, and I often felt weak, but now I feel like I have the inner strength to deal with anything that comes my way.”

We are currently learning attack and defence moves. “Look into the eyes of the person you are attacking,” Belraj Sir would reiterate. Each time he’d pick me as his opponent, I’d anticipate the pain and cringe. There are days when we students compare the blisters on our forearms, but this is only a minor price to pay. We’re gradually hoping to be introduced to sticks and daggers and swords. Full training demands a temple-like environment and a residential schedule with one’s guru.

I hope to get back soon to my mud pit for a month-long workshop. But before that, I need to perfect my split. “Push, push yourself a little more,” the instructions go. Believe me, I’m trying.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

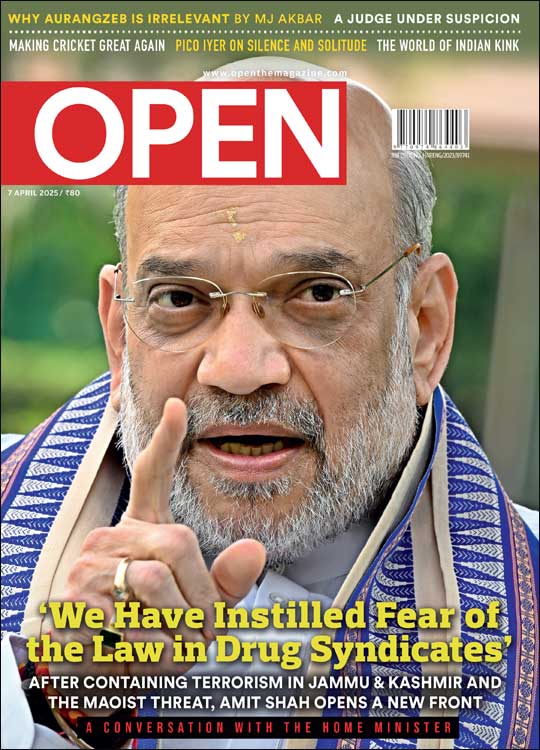

‘We Have Instilled Fear of the Law in Drug Syndicates,’ says Amit Shah

MOst Popular

4

/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Cover_Amit-Shah.jpg)

More Columns

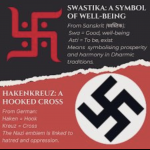

Elon Musk attracts sharp attack over ‘swastika’ from Indians on social media Ullekh NP

Yunus and the case of a "land locked" imagination Siddharth Singh

Why CSK Fans Are Angry With ‘Thala’ Dhoni Short Post