The Middle Ground

Earnest mediation between Maoist rebels and the Indian State could yet yield peace

Boyd Fuller

Boyd Fuller

Boyd Fuller

|

11 Apr, 2013

Boyd Fuller

|

11 Apr, 2013

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/naxal-nego.jpg)

Earnest mediation between Maoist rebels and the Indian State could yet yield peace

The Delhi-based social activist Swami Agnivesh has often invited wrath for his position on various issues and has been at the receiving end of abuse for making controversial statements. But nothing has generated as much fury as his stand on the Maoist issue after he was appointed an interlocutor by the Government for talks with Maoist rebels in 2010. Last year, after he made a statement condemning the Government for an incident in which 18 Tribals were killed in Chhattisgarh, among many vitriolic letters he received, one read: ‘What are you preaching lately about the Chhattisgarh encounter? Who gave you the authority to [term it] fake? Did you lose your pay cheque from your connections aka communists and Maoists? Or have you lost a beloved family member of yours to justify such sympathy?’

Agnivesh’s brief appointment as interlocutor ended abruptly in 2010 after senior Maoist leader Azad, who had been in touch with him on the possibility of talks, was gunned down in an apparent false encounter. “So this is what it means to be one of us,” he smiles.

Mediation is new turf in India. There are more variations of words in use to describe the skill than there are people who know what they mean. It was only in 2003 that the Supreme Court of India approved the model rules of mediation framed by the Law Commission. The high courts of Delhi and Karnataka were the first to formally launch the practice and training of court-annexed mediation, and slowly several other high courts across the country caught up. But so far, this has mostly been used to resolve family disputes. Using professional mediation for political or armed conflict resolution has never been tested.

India’s last noteworthy effort to mediate an armed conflict began in 1997, when a group of former government officials, intellectuals and civil society members came together as the Committee for Concerned Citizens (CCC), with a single aim to stop a spiral of violence between Naxalites and the Andhra Pradesh government. The CCC, spearheaded by the bureaucrat SR Sankaran, had a formula that helped the body position itself as an important voice: stand for the victims; be impartial between Maoists and the government.

In early 2002, the CCC eventually placed before the Andhra government and Naxalites an equal set of demands that were directly derived from the concerns of people at large. They insisted that Naxals stop using land mines to attack the police because that put locals at risk of being used as human shields by the police. They also demanded that the government lift the ‘wanted’ price on the heads of Naxal leaders because it only encouraged instances of police torturing locals to extract information on their movement.

Sankaran had the respect of both sides for his untainted public image as a man with strong moral values. The CCC had several senior journalists as well, which helped galvanise public opinion on the issue, thus giving ordinary people a stronger say as an interested party that could hold both sides to account. By constantly pushing both to set a code of ethics against which they could be held accountable, the CCC created the conditions for a gradual de-escalation of the violence. Finally, in 2004, both parties agreed to come forth for talks.

The mood in Hyderabad was euphoric when the rebels came out of the jungles openly for the first time. Naxal leader Akkiraju Haragopal alias Ramakrishna held durbars at Manjira Guest house where the rebels stayed and talks were held. “[YS Rajasekhara Reddy, then Andhra CM] used to conduct his durbars at Lakeview guesthouse. These eight days nobody attended his durbars. Right from police officers to revenue officers to divorce cases, all were brought to the Maoists to solve,” recalls Maoist ideologue Varavara Rao.

Unfortunately, the ceasefire agreements struck at these talks within months and a fierce battle erupted between Naxals and the government. While the Naxal leadership used this time to consolidate positions, the government’s intelligence apparatus used this opportunity to create moles within Naxals. Soon afterwards, a sustained operation against Naxals saw them being written off in Andhra Pradesh.

“Sankaran became very quiet after the talks failed. For a long time, he wrote nothing or said nothing. It was emotionally devastating for him because he really believed that the talks would lead to something permanent,” recalls CCC member Anant Maringanti.

So, is the Indian State really serious about mediation?

When Roger Fisher, former director of the Harvard Negotiation Project was once asked if he could really negotiate with a terrorist, he said, “I’d much rather listen to them than fight. A lot of times they’ve got legitimate grievances packaged as extreme political positions.”

Fisher is referring to the fundamental rule of conflict resolution: never negotiate positions, find interests. While a position is what we state we want externally (‘extreme political positions’), an interest reveals our underlying needs (‘legitimate grievances’). Put another way, many negotiators argue over solutions when they don’t even know what problem the other side is trying to solve.

Today the Maoist leadership may be seen as pursuing a utopia. But in their areas of influence, Maoists are popular among locals because they seem to have answers to ‘legitimate grievances’. As former Union Home Secretary GK Pillai wrote in an article in 2010: ‘They (Maoists) typically operate in what they see as a perceived administrative vacuum…Believe me if I say today… those 141 villages have not been seen by anybody in either the State or Central Government since 1969. Nobody has ever gone to them. There is not a single road, there is no BDO (Block Development Officer), no village officer, but we know they exist because the Maoists have come there.’

“The Indian State does end in these places. So the battle is about control on territory,” says Mariganti. One way of beginning to regain that control is by going local, he feels. It is important to pay attention to regional specifics of the movement rather than discussing a blanket set of issues at a national level. For instance, in Andhra, the issue was Tribal land getting transferred to non-Tribals. In Odisha, it is land, mining-induced destruction of tribal habitation, and tourism. In Chhattisgarh, it is mining, displacement and gross human rights violations; and in West Bengal, the movement is a fight against police atrocities inflicted on Tribals.

Charting Mediation Turf

In March 2012, former bureaucrat BD Sharma received a phone call from Maoists at his residence in Delhi. Sharma, a former commissioner of SC/STs and district magistrate in Bastar who had quit the administration in opposition to a Rs 2,000 crore pulp-and-paper industrial project, now heads a civil society outfit called Bharat Jan Andolan that advocates SC/ST rights. The Maoists who called wanted Sharma to mediate on their behalf with the Odisha government in a case of kidnapping of two Italian tourists. The Maoists then went on to brief him on a 13-point list of demands they had come up with.

“My first question then was that I must have both sides before I give a verdict! How can a mediator also represent the parties?” recalls Sharma. In asking for ‘both sides’, he touches upon a dilemma the Indian Government has been facing for long: how does one negotiate with a banned party? Does the Government lift the ban on party members when they come to the table? Or should Maoists be made to choose representatives who are officially outside the party and yet speak on their behalf? A negotiation via middlemen makes matters difficult. For one, it does not allow a relationship that can ease the candid sharing of information and enable creative thinking. The party tends to set out hard and inflexible demands for its representative to parrot at the talks, thus taking away the possibility of exploring better options for moving forward.

Additionally, such a setup automatically gives the Government more ‘voice’ by virtue of its physical presence.

Dandapani Mohanty, trade unionist and social activist in Berhampur, Odisha, has repeatedly pleaded with the Centre to allow captive Maoist leaders to be brought under police custody to the negotiating table. “This is not impossible to do, as Ganti Prasada was brought from Hyderabad to Jharpada jail in Bhubaneswar in February 2011 to negotiate the release of the then Malkangiri collector R Vineel Krishna,” he points out.

But how can a mediator represent one side and still expect to maintain credibility with the other? A mediator needs to be dedicated to making the negotiations work for all parties. That is what distinguishes him from an interested party, who is focused only on his own interests.

Keeping neutral is harder than one can imagine. Some toe a thin line between mediation and activism.

According to Sharma and others, an integral part of the mediator’s role is to “give a verdict” on who is right and who wrong, just as village elders do in rural panchayats after hearing both sides of a dispute. Swami Agnivesh echoes this when he says, “A mediator has a moral duty to say who the culprit is.” But should a mediator play judge? Not in these cases; its constitutionality apart, none of the parties has any liability to abide by such a verdict.

To make peace, a professional mediator devises a process that the parties recognise as fair and worth pursuing. The parties have to feel that they have been able to push their interests to the fullest in the negotiation and that the solution is better for each than the status quo. In such cases, an impartial and skilled mediator is required who can enable parties to wade through the animosity, mistrust and political dynamics to arrive at a mutually beneficial solution.

The sense of responsibility to a self-created agreement ensures commitment. A party is more likely to call a ceasefire because it meets its interests than because its representatives were cajoled or reprimanded by mediators who lack any real authority to compel action.

A Case for Mobile Mediation

In February 2011, when Malkangiri Collector R Vineel Krishna of Odisha was kidnapped by Maoist rebels, the latter suggested that Mohanty and Professor Haragopal, a civil rights activist and key founder of the erstwhile CCC, be made mediators. Surprisingly, the Odisha government agreed to have the two mediate on both sides. Instead of assembling at a venue to mediate, Mohanty and Haragopal made several trips to meet the rebels, meeting Ganti Prasada at Jharpada jail, and Odisha’s home secretary and panchayat secretary at their offices at Bhubaneswar, carrying messages back and forth.

The Maoist party had 14 demands, of which their priorities was the release of innocent Tribals who they said had been imprisoned on false charges, the release of five of their leaders, and the return of Tribal land under the occupation of non-tribals. “We had a lot of persuading to do on both sides,” says Haragopal. “Finally when committees were appointed for the release of prisoners and transfer of land, we held a press conference and said ‘This is the most we can get out of this for both sides, now release the collector within 48 hours; no more dialogue’,” recounts Haragopal.

Both sides agreed.

Haragopal feels this was a smooth mediation where both parties got most of what they wanted. Ironically, the Odisha case received much criticism from the public and media: how could both parties ha ve had the same mediator? Moreover, how could a government agree so readily to the use of mediators named by Maoists?

Walking a Razor’s Edge

At Odisha’s Berhampur town, as you enter Dandapani Mohanty’s modest bungalow, his ferocious looking hound greets you with eager sniffs. As soon as you’ve taken your seat, Mohanty coolly informs you that he is under surveillance and his phone lines are permanently tapped. At times, he gets roped into becoming a ‘mediator’ for Naxalites—such as in the negotiation of the release of collector Vineel Krishna in 2011 and of the Italian tourists in 2012. “Whenever I try reminding the government to stick to its commitment, I get death threats on my phone. And Maoists hold me responsible for ensuring that the government does what it has promised,” says Mohanty. Sometimes, mediation is like walking a razor’s edge.

Today Mohanty is in prison. On 9 February 2013, a few months after giving an interview for this story, he was arrested by the Odisha Police on charges of being involved in Maoist activities.

Sujato Bhadra, a mediator appointed by West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee to host talks with Naxalites in Lalgarh, minces no words in saying that talks are just a show. Banerjee had used “dealing with Naxalites in a humanitarian way” as part of her election campaign in 2009, and her Trinamool Congress party won power in the state. But soon after Bhadra and his team had finalised modalities for talks in September 2011, she was quick to call it quits. In November year, senior Maoist leader Kishenji was shortly killed in an alleged fake encounter.

“The Government is more responsible for talks breaking down,” says Bhadra, “Our agreement was not given due importance. Mamata was liquidating us by keeping us inactive and sending armed forces despite a ceasefire agreement. So we retired from mediation.”

Agrees Sharma: “There are 101 ways of delaying what we’ve agreed upon. Commitment is simply not the culture of the Indian State.”

Haragopal believes that anger within the police tends to guide anti-Naxal state policy. When he was speaking to Chhattisgarh Chief Minister Raman Singh about negotiating the release of collector Alex Paul Menon last year, the DGP present got furious. “‘Are we not dying? So what if they kill the collector?’ he asked, ‘This country should learn to sacrifice’,” in Haragopal’s words.

The question is: does the Government get a better deal by not coming to the negotiating table? A cover story published in the 27 August 2012 issue of Open, ‘The final battle of Sabyasachi Panda’ has excerpts from an open letter written by Odisha’s top Maoist commander that was critical of the party for its high-handed leadership, hegemony and exploitation of its own cadre. ‘Beating and burning or eliminating someone by simply stamping him/her [an] informer is not the solution,’ wrote Panda, who left the CPI (Maoist) to form his own outfit.

If the dissent-torn movement is likely to fizzle out on its own, some ask, why waste time on talks?

It is true that the party is at threat of fragmentation. “It has failed to capture the imagination of local populations because it has failed to take up their issues. The Maoist party only supports other people’s movements but has failed to create any of its own,” according to Mohanty. People within the party are also beginning to question the need for so much violence. “This ‘gun culture’ developing within the party is not right.”

And besides, are Maoists any more earnest in asking for talks?

“The mediators probably didn’t realise that the real interest of the Maoist party in coming for the 2004 talks was to expose the wrongdoings of the government and influence the urban middle-class,” says Varavara Rao, who adds that this motivation holds true even today.

Give Mediation a Fresh Shot

Early this year, the Government came up with a plan to establish hostage negotiation teams in conflict states. These would be positional in nature without recognising the unfulfilled underlying interests that are desperate for public attention. According to Mohanty, Maoists kidnap hostages to draw the State’s attention to their grievances.

In a recent article in Outlook, Sociology Professor Nandini Sundar of Delhi University writes: ‘Since all political parties are united on the militarist approach, there is no political pressure to act, and no one to challenge the government to “abjure” its own violence.’ She suggests a semi-permanent group of interlocutors ‘to have sustained discussions on peace talks, as against the knee-jerk use of mediators in times of hostage crises’.

Varavara Rao feels that efforts should be collective. “Sankaran was the convenor of the CCC in letter and spirit. At no point did he take any decision alone. He had at least a group of four or more members who he went with everywhere. This is what I keep telling Agnivesh. This type of individual functioning will not do for such a serious matter as peace talks.” “At the end of the day, this is a political war that needs political solutions,” says Maringanti. The question is of the methods a State should adopt to find these solutions. If getting rid of Naxalites was the goal, it would be an understatement to say that the State has failed miserably. Today, a third of India is directly affected by the movement in some form or another. It is now time to give mediation an earnest chance.

To start, we need more analysis of the parties’ main concerns and what issues they could genuinely discuss. A glance at the CPI (Maoist)’s demands at recent negotiations on the Italian hostages reveals the following concerns: i) release of political prisoners, ii) an end to Operation Green hunt and police atrocities, iii) protection of Tribal land (from deforestation, industrialisation and mining), iv) empowerment of gram sabhas, v) banning of sales of imported liquor in villages (to protect the local liquor industry, a source of livelihood).

Instead of seeking peace rightaway, it is better to start with small steps: building relations among the parties, developing their negotiation and listening skills as they interact, learning more about what each party is really concerned about, and then perhaps making agreements on issues that are easy to implement and monitor so that trust can gradually be built.

Boyd Fuller teaches Negotiation at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore. Shriya Mohan is an independent journalist

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

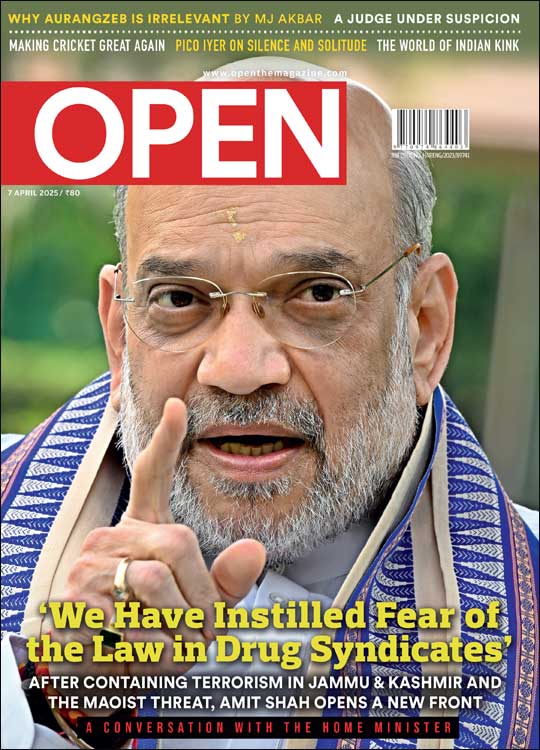

‘We Have Instilled Fear of the Law in Drug Syndicates,’ says Amit Shah

MOst Popular

4

/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Cover_Amit-Shah.jpg)

More Columns

BJP allies redefine “secular” politics with Waqf vote Rajeev Deshpande

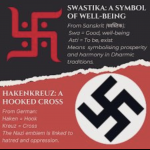

Elon Musk attracts sharp attack over ‘swastika’ from Indians on social media Ullekh NP

Yunus and the case of a "land locked" imagination Siddharth Singh