A reckless script gone so horribly wrong that a happy ending is unbelievable, if not impossible.

SAWAI MADHOPUR ~ It was nearing noon. Standing on the high western bank, I could see a broken layer of mist still hanging on the Chambal river. The gentle slopes leading to the water glistened with promising crop. About a hundred yards to my left, the slope became steeper where the Kharad nallah, a minor tributary, joined the mighty river. Behind me, red gram (arhar dal) crop stood four feet tall on a rectangular field. Less than 50 yards to the right, shrubby growth of thorny vegetation broke the monotony of green.

Walking single file, forest officials were looking for pugmarks so that they could warn the farmers working nearby. A tigress and her two cubs had killed a cow barely a kilometre away four days ago. Range Officer Jodhraj Singh Hada had already deployed eight men to keep track of the runaway family. Now he was out in the field himself to assess the ground situation.

Clearly, nobody except me was expecting any miracle. But then, these were hardened forest hands, and this was only the fifth time I was looking for tigers on foot. So while I wistfully surveyed the vegetation around, most eyes scanned the ground next to their feet. If we spotted fresh pugmarks, I was told, we would count ourselves lucky.

Walking about 50 yards ahead of me, Hada spotted a lonely farm hand and stopped to give a routine warning. Forester Mahavir Sharma was keeping pace with me. Earlier, as we drove past sprawling mustard fields, he had laughed off the possibility of black-and-golden stripes darting out of a sea of yellow. “Try spotting a tiger here,” he chuckled again, pointing at the standing red gram crop to our right that shuttered vision more effectively than Venetian blinds. I smiled sheepishly and stopped looking.

Two forest guards who were painstakingly scouting the slopes below for pugmarks suddenly decided to catch up with us. Possibly their upward momentum took them a few yards inside the red gram field. Ahead of us, Hada was now standing in an open ploughed ground, looking for that farm hand. Mahavir and I also veered to the right to cut distance.

Perhaps the four of us formed a human chain too close-knit for comfort. Out of the blue, I heard an angry rumbling. Through the corner of my right eye, I caught a glimpse of at least two big cats making a dash in our direction barely ten yards away. The next second, I could only see the vegetation sway and Mahavir dash away. The rumbling of the growl only got louder. Unsure and terrified, I blindly lunged forward.

My desperate lunge got me entangled in a bush of thorny Prosopis juliflora. But the tigress, known as T13 in Ranthambhore, had no intention to harm any of us. She was worried for her cubs and had just warned us before we got too close for mutual safety. For more than a month now, her close vigil against people has worked. But the next time, her nerve may not hold.

On 26 December, the Ranthambhore management launched a search after T13 and her cubs had been missing for 22 days. On 29 December, forest guards found their pugmarks, and the same day, a blue bull kill made by T13 was spotted near Senwati Dharmpuri, more than 10 km from her home range inside Rajasthan’s famous national park.

Bodol forester Sudarshan Sharma saw the family the day the blue bull kill was found. He noticed that one of the cubs was bigger, implying a male. But why did he lose track of the family? How did the three big cats leave the reserve unnoticed? Sudarshan claims the canny tigress took the hilly ridge behind his range via Bheronpura village and then took the Kundli riverbed to reach the Chambal. To be fair, if tigress T13 had managed to give her murderous suitors the slip, Sharma stood little chance.

To complicate matters further, T13’s aging mother, T14, has also been pushed out of the reserve by younger competitors. The old tigress is now fighting her last battle for survival in the same ravines not too far away from her daughter’s family. While T14’s days are numbered, aged tigers wandering close to habitations have a history of getting into conflict with humans. If the old granny ends up attacking people, the mother and cubs may have to face the ire of villagers.

Meanwhile, out in the ravines, T13 made her first cattle kill on 2 January near Lasora village. Ranger Hada promptly swung into action. Forest guards recovered the remains of the kill the next day to leave no room for poisoning. On 7 January, a local NGO raised funds through its volunteer network to compensate for the kill. With Rs 5,000 each coming from the volunteers and government, Bhuvanya Bairwa admitted that he would make a small profit on the bull he lost to the tiger.

Lasora sarpanch Tej Singh appeared a reasonable man. Before posing with Bairwa and Mahavir for photographs while handing over the compensation, he did ask Hada how soon the ranger would take away those tigers. But when told that the mother and cubs might turn the village’s fortune around, Singh listened carefully. Hada explained that thanks to the tigers, Lasora had already been added to a list of villages that will benefit from a new Rs 12 crore ‘tiger fund’ meant for micro development. Now Singh was nodding easily; so a little routine advice followed on the precautions to be observed while the tigers were around. It was a breeze. The few villagers present readily agreed to comply. Relieved, a confident Hada went scouting for pugmarks.

But the growling, darting tigers were surely more than what the forest staff had bargained for. Immediately after the scare, Hada readily accepted suggestions from Dr Dharmendra Khandal, noted field biologist who generated supplementary compensation for the cattle kill, to preempt conflict. With a frown on his forehead, the ranger set out to plan daily village meetings, pamphlets for distribution and even media advertisements.

But the media has already lapped up the story, explaining the runaway tigress as a victim of over-population. Intimidated by too many males, forest bosses explained, tigress T13 fled the reserve to save her cubs. For the record, the tigress was photographed on 1 October last year. Next morning, she was seen fighting and pushing a male tiger, T28, almost 3 km back from Ranthambhore’s Ada Balaji main road to Goolar Kui. That night, she was seen by the forest staff at the main road barrier with her cubs. The next day, she boldly crossed the tar road with her cubs and probably started her journey away from the nasty males.

In the absence of the tiger that sired T13’s cubs, any other male tiger seeking to mate with her would first kill the cubs to establish its own bloodline. Also, it is not rare for a male tiger to be killed or chased away by a more able adversary. But the father of T13’s cubs was not eliminated by nature. Tiger T12, one of Ranthambhore’s four dominant males then, was airlifted to Sariska last year in a joint exercise by the state forest department, Wildlife Institute of India and National Tiger Conservation Authority.

After the first three translocated tigers turned out to be siblings (‘Conservation: the New Killer,’ Open, 24 July 2009), the Sariska repopulation drive was put on hold and a thorough DNA test was ordered (‘Centre Orders DNA Test for Tigers,’ Open, 24 February 2010). The fourth tiger was to be picked up based on this DNA report (‘DNA Tests Confirm Sariska Siblings,’ Open, 26 June 2010). But the officials inexplicably decided to overlook other crucial criteria. A Union ministry guideline clearly stated that only young transient tigers could be selected for translocation. Nevertheless, forest officials shifted a mature male tiger, which had already impregnated a tigress, T13 (‘Dispatched to Die,’ Open, 19 November 2010).

It was nothing short of a pre-natal death sentence for the cubs. Only a really exceptional mother could raise her cubs in the absence of their father. And so far, T13 has done a great job.

But life around Lasora is on the edge. The people here are simple, unlikely to target the big cats if they get timely, adequate compensation for livestock losses. Between Hada and Dr Khandal, they have a sound assurance. But an accidental attack on people—a distinct possibility during the crop gathering due next month—can change the entire equation. T13 needs to shield her seven-month-old cubs for another 13-17 months. Major conflict is inevitable if the family stays put in the cropland and ravines for that long.

Presence of ample livestock and some wild prey in the fields along the Chambal river may discourage major movement of the family. However, it is not really practical to tranquilise all three tigers simultaneously, which is essential to keep the family together. In any case, taking the family back to the national park will again expose the cubs to dominant males, and the tigress’ courageous foray into the unknown to save her young ones will come to naught.

The tigress has not tried to cross the Chambal river yet, probably because her cubs are too young to risk the tide. But if the trio does move onto the other side of the river in the months to come, they will enter a very crowded landscape and may run into poachers. While gunmen may hit them even at their present location, it is easier to secure the area, flanked as it is by the tiger reserve and the river. In recent times, few Ranthambhore tigers that crossed the Chambal have survived.

So, is there no hope for T13 and her cubs? Nature is never short of possibilities. Male tigers do not harm young females that are potential mates. So if both cubs of T13 are female, the family may well be rehabilitated if it moves back to Bheronpura area in the Sawai Man Singh sanctuary, about 6 km from its present location. Bheronpura has a small but good tiger habitat without any resident tiger and is only occasionally scouted by a couple of male tigers.

However, if Sudarshan’s observation is right, T13 will be wary of venturing anywhere close to the forest with a male cub. Unfortunately, a growing male cub in the cropland may also increase the chances of conflict.

Ranger Hada and his team of ground staff have a thankless job at hand. These foot soldiers of conservation are now expected to undo the damage done by their mighty generals. Rajasthan’s chief wildlife warden HM Bhatia went on record last week accepting that T12 is the father of T13’s cubs, but did not explain why the tiger was packed away. The WII scientists who picked up T12 after handpicking three siblings are still at the helm of the country’s most ambitious conservation project. The NTCA has not explained why it flouted its own guidelines by allowing the translocation of a dominant male.

It will take great resolve and much greater luck if the ground staff are to secure the future of T13 and her cubs. However, it should take Environment and Forests Minister Jairam Ramesh much, much less to fix some accountability, somewhere.

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/single-mother.jpg)

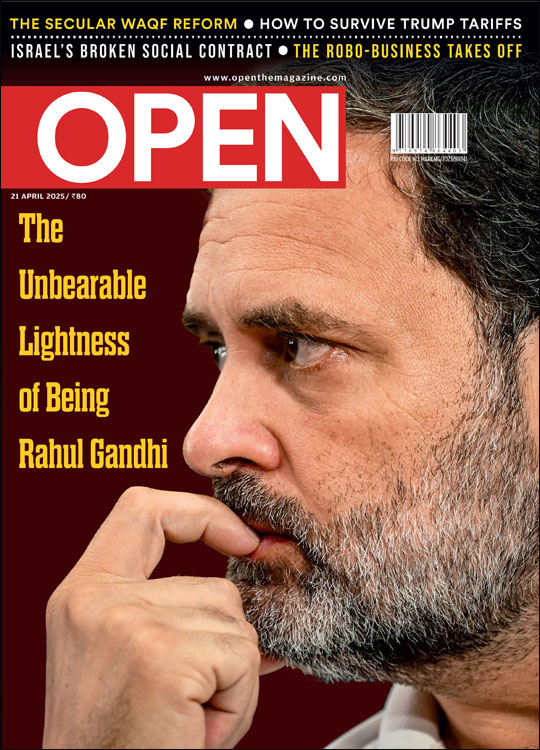

/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Cover-Congress.jpg)

More Columns

Maoist eco-system pitch for talks a false flag Siddharth Singh

AI powered deep fakes pose major cyber threat Rajeev Deshpande

Mario Vargas Llosa, the colossus of the Latin American novel Ullekh NP