/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/18524.publicsqure1.jpg)

For so long, the intellectual establishment of India was sustained by the twin pillars of Marx and Nehru. Those who deviated from the left side of history were relegated to the margins as useless idiots. Things are changing, and there is diversity in the marketplace of ideas. So many erstwhile taboo words—from ‘nation’ to ‘religion’ to ‘wealth’—are being abandoned and an alternative narrative is emerging. Once the arguments were solely leftist and righteous, now the mainstream is no longer ideologically unipolar. The voices from the public square that reflect a new reality and abhor exaggerated authority form a new polyphony in tune with a new India. There are any number of arguments out there that focus on positive change, and add to the idea of a 21st century India where modernity is not a repudiation of traditions. Remember what Salman Rushdie said: “Religions, like all other ideas, deserve criticism, satire, and, yes, our fearless disrespect.” Nothing is sacred for him. So it should be for any other public intellectual as well. Or think of someone like Chandra Bhan Prasad, who unapologetically espouses rightist economic growth as a key tool for drawing Dalits into the country’s mainstream. The variety you see in the Indian public square is a tribute to a confident democracy where icons are blasted, rebuilt and kept under the permanent gaze of the questioning mind.

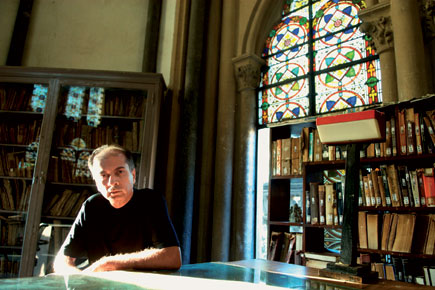

A WRITER’S WORLD: Salman Rushdie, Novelist, 67

He is greater than his oeuvre; he touches upon key moments in the ideological war that has shaped the modern world to campaign against the tyranny of organised religion. With despotism reaching a crescendo globally, Rushdie is once again in an indefatigable intellectual engagement with the world, tweeting in irreverence and batting for Charlie Hebdo when many other authors have taken issue with the PEN American Center’s decision to honour the weekly with its Freedom of Expression Courage award. One would think that condemning the killing of cartoonists in the name of religion forecloses disagreement in the liberal world, but Rushdie has had to repeatedly defend his defence of the art of satire, even vis-a-vis The Times Literary Supplement, which, to the surprise of many, accused him of ‘intellectual complacency’.

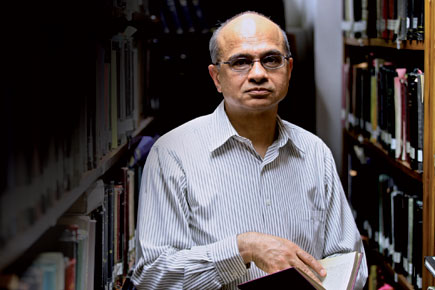

THE OPINIONATOR: Pratap Bhanu Mehta, Political Scientist, 48

No other scholar has positioned himself as squarely, and with such intellectual equanimity, in the middle of Indian politics. A pre-eminent political philosopher of our times, Pratap Bhanu Mehta has dismantled the stereotype of the public intellectual to pen passionate wake-up calls on the destructive governance of the UPA. Mehta’s mature reading of the political climate is crosshatched with the rhetoric of a change agent. His highly convincing essays deconstruct obvious binaries and inspire much public discussion. But Mehta is not just a theorist blessed with incisive clarity; he is pro-action, arguing for decisive leadership, and displays firm commitment to institution-building that reflects in the work of the Centre for Policy Research, a think-tank he heads. He resigned as member-convenor of the National Knowledge Commission, disappointed with the UPA regime’s ‘politics of illusion’ after it proposed quotas for OBCs in higher education. Mehta’s role in moulding India’s public discourse remains peerless.

No other scholar has positioned himself as squarely, and with such intellectual equanimity, in the middle of Indian politics. A pre-eminent political philosopher of our times, Pratap Bhanu Mehta has dismantled the stereotype of the public intellectual to pen passionate wake-up calls on the destructive governance of the UPA. Mehta’s mature reading of the political climate is crosshatched with the rhetoric of a change agent. His highly convincing essays deconstruct obvious binaries and inspire much public discussion. But Mehta is not just a theorist blessed with incisive clarity; he is pro-action, arguing for decisive leadership, and displays firm commitment to institution-building that reflects in the work of the Centre for Policy Research, a think-tank he heads. He resigned as member-convenor of the National Knowledge Commission, disappointed with the UPA regime’s ‘politics of illusion’ after it proposed quotas for OBCs in higher education. Mehta’s role in moulding India’s public discourse remains peerless.

HISTORIAN AT LARGE: Ramachandra Guha, Hisotrian and Biographer, 57

A protean thinker with a corpus straddling several disciplines in the humanities and social sciences, not to mention his works on cricket, Ramachandra Guha’s books are landmarks in the interpretation of 20th-century India, demystifying the story of the modern nation-state for large swathes of readers who would normally be averse to shouldering the scholarly burden of non-fiction. His stock soared with India After Gandhi, a fluent reconstruction of post-Independence history, but he has remained an unselfconscious academic who is sharply critical of intellectual egotism and excited at the prospect of real research. Equal parts social anthropologist and liberal intellectual, and a shrewd wordsmith, Guha is an important interlocutor in the exchange of ideas on the many Indias. Few academics in India can claim to have as much currency.

A protean thinker with a corpus straddling several disciplines in the humanities and social sciences, not to mention his works on cricket, Ramachandra Guha’s books are landmarks in the interpretation of 20th-century India, demystifying the story of the modern nation-state for large swathes of readers who would normally be averse to shouldering the scholarly burden of non-fiction. His stock soared with India After Gandhi, a fluent reconstruction of post-Independence history, but he has remained an unselfconscious academic who is sharply critical of intellectual egotism and excited at the prospect of real research. Equal parts social anthropologist and liberal intellectual, and a shrewd wordsmith, Guha is an important interlocutor in the exchange of ideas on the many Indias. Few academics in India can claim to have as much currency.

INDIA ON HIS MIND: Sunil Khilnani, Political Scientist, 55

There are numerous theories on why India has been a successful democracy but no consensus. Sunil Khilnani, a professor of politics and director of King’s India Institute, King’s College London, goes beyond that question—into what India is. His most famous book, The Idea of India, is regarded as a definitive tome on the subject by many, not just in India but across the world. According to a review in The New York Times , it is ‘a meditation on the experience of the 50 years of India’s existence as a nation that emerged, battered and sliced, when the British withdrew from colonial rule and partitioned the subcontinent in the process.’ Khilnani is recognised as one of the world’s foremost political scientists on India. Beyond his academic papers, he regularly publishes his ideas in the mass media for a wider audience both here and overseas. Along with the history of Indian democracy, which is his forte, Jawaharlal Nehru has also been a subject of Khilnani’s research for a long time now.

There are numerous theories on why India has been a successful democracy but no consensus. Sunil Khilnani, a professor of politics and director of King’s India Institute, King’s College London, goes beyond that question—into what India is. His most famous book, The Idea of India, is regarded as a definitive tome on the subject by many, not just in India but across the world. According to a review in The New York Times , it is ‘a meditation on the experience of the 50 years of India’s existence as a nation that emerged, battered and sliced, when the British withdrew from colonial rule and partitioned the subcontinent in the process.’ Khilnani is recognised as one of the world’s foremost political scientists on India. Beyond his academic papers, he regularly publishes his ideas in the mass media for a wider audience both here and overseas. Along with the history of Indian democracy, which is his forte, Jawaharlal Nehru has also been a subject of Khilnani’s research for a long time now.

RIGHT ANGLE: Swapan Dasgupta, Political Commentator, 59

If the world of the Indian political right is divided between the loony fringe and the liberals, then Swapan Dasgupta has been a leading light of the latter for some time now. He has been consistent and open in his political leanings. When the Congress- led UPA was in power, NDTV aired a studio show in which Mani Shankar Aiyar, representing the left of the political spectrum, and Swapan Dasgupta, the right, jousted with each other. That Dasgupta was countering a career politician and former Union minister was indication enough of his political affliations. He shares a close relationship with many members of today’s ruling establishment in India. He is still a regular on prime-time TV news, his task of projecting a moderate image for the Right complicated of late by rising decibels of the loony fringe. Dasgupta, a historian by training, continues to come out with the most sophisticated arguments from the right side of the aisle.

If the world of the Indian political right is divided between the loony fringe and the liberals, then Swapan Dasgupta has been a leading light of the latter for some time now. He has been consistent and open in his political leanings. When the Congress- led UPA was in power, NDTV aired a studio show in which Mani Shankar Aiyar, representing the left of the political spectrum, and Swapan Dasgupta, the right, jousted with each other. That Dasgupta was countering a career politician and former Union minister was indication enough of his political affliations. He shares a close relationship with many members of today’s ruling establishment in India. He is still a regular on prime-time TV news, his task of projecting a moderate image for the Right complicated of late by rising decibels of the loony fringe. Dasgupta, a historian by training, continues to come out with the most sophisticated arguments from the right side of the aisle.

THE HAWK: Brahma Chellaney, Strategic Thinker and Author, 55

Long before he gained fame as a strategic thinker, he won recognition as a journalist covering Operation Bluestar, when he was in his early twenties. Now he is a sought-after wonk for advice by various governments,

Long before he gained fame as a strategic thinker, he won recognition as a journalist covering Operation Bluestar, when he was in his early twenties. Now he is a sought-after wonk for advice by various governments,

especially on Asian geopolitics. He is familiar with the region’s most dangerous hotspots, and his books are on the reading list of diplomats and policymakers. He tells the truth as bluntly as he sees it and likes to expose games of deception. He favours India responding to Chinese incursions by sending troops to Chinese-held territories and by forging partnerships with countries like Japan. Chellaney, a Bernard Schwartz awardee and a professor of Strategic Studies at the Delhi-based Centre for Policy Research, sees India as a force for stability in a continent that could end up under Chinese dominance. His influence in policy circles is the envy of rivals.

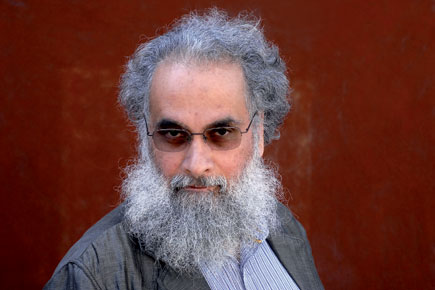

THE POST-ROMANTIC: Pankaj Mishra, Writer and Critic, 45

He is the odd global intellectual uncomfortable with the idea of globalisation. An erudite voice on imperialism and the abuse of power, Mishra’s specialty lies at the lofty intersection of literature and politics, the latter more than the former as he finds his niche in non-fiction and as an essayist sought after by the global media. Many in the West listen closely to him as he takes the pulse of India from his pad in London or his retreat in Mashobra, Himachal Pradesh. In his latest onslaught against India under Modi in The New York Times—an essay titled ‘Modi’s Idea of India’ that has provoked outrage within the country from an audience he has never sought to placate—Mishra goes a step further to warn against an ideology of ‘anti-imperialist imperialism’ emerging in ‘wannabe superpowers’ that can ‘make Islamic fundamentalists seem toothless’. It is such dazzling political imagination that powers Mishra’s polemic.

He is the odd global intellectual uncomfortable with the idea of globalisation. An erudite voice on imperialism and the abuse of power, Mishra’s specialty lies at the lofty intersection of literature and politics, the latter more than the former as he finds his niche in non-fiction and as an essayist sought after by the global media. Many in the West listen closely to him as he takes the pulse of India from his pad in London or his retreat in Mashobra, Himachal Pradesh. In his latest onslaught against India under Modi in The New York Times—an essay titled ‘Modi’s Idea of India’ that has provoked outrage within the country from an audience he has never sought to placate—Mishra goes a step further to warn against an ideology of ‘anti-imperialist imperialism’ emerging in ‘wannabe superpowers’ that can ‘make Islamic fundamentalists seem toothless’. It is such dazzling political imagination that powers Mishra’s polemic.

THE LEGAL EAGLE: Harish Salve, Lawyer and Former Solicitor General, 58

Living up to his reputation as the country’s most in-demand lawyer, he appeared in the Bombay High Court seeking bail for convicted Bollywood star Salman Khan. And Khan got the bail. Salve, former solicitor general of India, is arguably the most expensive lawyer in India. He handles very high-profile cases, including corporate disputes between the Ambani brothers and cases of embattled political bigwigs. His fee is so high that it is said that even the likes of billionaire Mukesh Ambani find it steep. Salve’s reputation for charging high fee comes at a time when lawyers are increasingly emerging as high networth individuals. His other corporate clients include the Tata Group, Vodafone and ITC. A piano player, Salve is well-networked and friends across political parties. His father NKP Salve was a senior Congress leader. A well-known columnist referred to him as the ‘first port-of-call for MNCs troubled with income-tax matters’.

Living up to his reputation as the country’s most in-demand lawyer, he appeared in the Bombay High Court seeking bail for convicted Bollywood star Salman Khan. And Khan got the bail. Salve, former solicitor general of India, is arguably the most expensive lawyer in India. He handles very high-profile cases, including corporate disputes between the Ambani brothers and cases of embattled political bigwigs. His fee is so high that it is said that even the likes of billionaire Mukesh Ambani find it steep. Salve’s reputation for charging high fee comes at a time when lawyers are increasingly emerging as high networth individuals. His other corporate clients include the Tata Group, Vodafone and ITC. A piano player, Salve is well-networked and friends across political parties. His father NKP Salve was a senior Congress leader. A well-known columnist referred to him as the ‘first port-of-call for MNCs troubled with income-tax matters’.

THE CRITICAL CHRONICLER: Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Historian, 53

A polyglot and a global citizen who now works at UCLA, Subrahmanyam is India’s foremost global historian. An accomplished chronicler of the early modern world, his body of work is overwhelming in its breadth and scholarship, offering a telescopic view of the 15th to the 18th centuries, the political economy of the age, its social mores, its sectarian conflicts and violence and its key protagonists. He is bitingly critical of India’s parochial and nationalist engagement with the past and argues for the study of the connective histories of nations. Indian history, he says, cannot be viewed as insular from the global context, and India itself should be seen as ‘a space open to external influences rather than a simple exporter of culture’. Subrahmanyam doesn’t restrict his scholarship to India or to narrow periods of history, and he is working on yet another book with longtime collaborator Muzaffar Alam on a social and cultural history of early modern India drawn from first-person narratives.

A polyglot and a global citizen who now works at UCLA, Subrahmanyam is India’s foremost global historian. An accomplished chronicler of the early modern world, his body of work is overwhelming in its breadth and scholarship, offering a telescopic view of the 15th to the 18th centuries, the political economy of the age, its social mores, its sectarian conflicts and violence and its key protagonists. He is bitingly critical of India’s parochial and nationalist engagement with the past and argues for the study of the connective histories of nations. Indian history, he says, cannot be viewed as insular from the global context, and India itself should be seen as ‘a space open to external influences rather than a simple exporter of culture’. Subrahmanyam doesn’t restrict his scholarship to India or to narrow periods of history, and he is working on yet another book with longtime collaborator Muzaffar Alam on a social and cultural history of early modern India drawn from first-person narratives.

POLITICAL BRAIN: Atul Kohli, Academic, 62

Perhaps no other academic—he is a scholar’s scholar—has analysed in such depth and detail the real dangers India is expected to face. In his 2012 book, Poverty Amid Plenty in the New India, he covered the country’s political economy over the past three decades, a period that saw rapid growth and a sharp rise in inequality. Long before the polls of 2014, he had warned that a pro-business ruling alliance and its policies had created a host of new political problems. He said our rulers underestimate class anger. The outcome of the General Election proved him right. Over the years, Kohli has impressed readers with his analyses of cronyism and corruption, apart from electoral volatility and demagoguery in several states, dysfunctional cities in which the solution to public problems are essentially privatised, the Naxalite phenomenon and farmer suicides. A longer term political problem in the making, he said, is a shift in power within India to the wealthier states of western and southern India. This will pitch the power of numbers that favour the Hindi heartland against the power of resources and talent that favours better-off states, the Jhansi-born Princeton professor argued. What’s needed, he believes, is real inclusion.

Perhaps no other academic—he is a scholar’s scholar—has analysed in such depth and detail the real dangers India is expected to face. In his 2012 book, Poverty Amid Plenty in the New India, he covered the country’s political economy over the past three decades, a period that saw rapid growth and a sharp rise in inequality. Long before the polls of 2014, he had warned that a pro-business ruling alliance and its policies had created a host of new political problems. He said our rulers underestimate class anger. The outcome of the General Election proved him right. Over the years, Kohli has impressed readers with his analyses of cronyism and corruption, apart from electoral volatility and demagoguery in several states, dysfunctional cities in which the solution to public problems are essentially privatised, the Naxalite phenomenon and farmer suicides. A longer term political problem in the making, he said, is a shift in power within India to the wealthier states of western and southern India. This will pitch the power of numbers that favour the Hindi heartland against the power of resources and talent that favours better-off states, the Jhansi-born Princeton professor argued. What’s needed, he believes, is real inclusion.

THE PROSELYTISER: Sadanand Dhume, Journalist and Author, 46

Over the years, this Washington DC-based Indian journalist has established himself as one of the most widely read commentators on Asia, global affairs and Islam as practised by large numbers in the non-Arab world. He made a mark with his 2008 travelogue, My Friend the Fanatic: Travels with a Radical Islamist, which captures the rise of Islamism in Indonesia. Dhume, who is currently working on a book on the impact of globalisation in India, is also regarded as an expert on terrorism and the culture wars between the West and Islam. An alumnus of Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, he also holds a Master’s in journalism from Columbia University. He was a correspondent of The Far Eastern Economic Review in Indonesia, and has written extensively in globally read publications such as The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Forbes and Foreign Policy. He has won widespread recognition for his essays on India and Pakistan, security and Southeast Asian culture and politics.

Over the years, this Washington DC-based Indian journalist has established himself as one of the most widely read commentators on Asia, global affairs and Islam as practised by large numbers in the non-Arab world. He made a mark with his 2008 travelogue, My Friend the Fanatic: Travels with a Radical Islamist, which captures the rise of Islamism in Indonesia. Dhume, who is currently working on a book on the impact of globalisation in India, is also regarded as an expert on terrorism and the culture wars between the West and Islam. An alumnus of Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, he also holds a Master’s in journalism from Columbia University. He was a correspondent of The Far Eastern Economic Review in Indonesia, and has written extensively in globally read publications such as The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Forbes and Foreign Policy. He has won widespread recognition for his essays on India and Pakistan, security and Southeast Asian culture and politics.

WAR OF IDEAS: Srinath Raghavan, Historian, 38

Few academics of his generation can claim to be as prolific. A former infantry officer, Srinath Raghavan’s PhD dissertation at King’s College, London, resulted in a brilliant debut, War and Peace in Modern India. Straddling the disciplines of international relations and history, it presented a balanced study of Nehru’s foreign policy and his liberal realism. Raghavan is a rare columnist with an enviable knack for making scholarly research easily accessible to readers even as he draws from previously untapped archival material to make sense of the conflicts that framed the past century. After a monumental book on the history of the creation of Bangladesh, his eagerly-awaited India’s War: The Making of Modern South Asia, 1939-45 is expected to consolidate his position as a respected chronicler of modern history and international politics.

Few academics of his generation can claim to be as prolific. A former infantry officer, Srinath Raghavan’s PhD dissertation at King’s College, London, resulted in a brilliant debut, War and Peace in Modern India. Straddling the disciplines of international relations and history, it presented a balanced study of Nehru’s foreign policy and his liberal realism. Raghavan is a rare columnist with an enviable knack for making scholarly research easily accessible to readers even as he draws from previously untapped archival material to make sense of the conflicts that framed the past century. After a monumental book on the history of the creation of Bangladesh, his eagerly-awaited India’s War: The Making of Modern South Asia, 1939-45 is expected to consolidate his position as a respected chronicler of modern history and international politics.

THE CRUSADER: Apoorvanand, Academic, 52

Columnist Apoorvanand Jha, who mostly prefers to use his first name, is a scholar of Marxian aesthetics. He is a committed Leftist who holds sway over his readers with his incisive and sharp commentaries on the Indian right and corporate interests, besides his write- ups on Indian culture and society. He is simply the most widely read Leftist writer in North India. Scholars, journalists and people opposed to rightwing politics are under the spell of this Delhi University professor, who was born and raised in Siwan, Bihar. A PhD from Patna University, he has also played a significant role in setting syllabii for students, especially in redesigning the academic programme of the Hindi department at Delhi University. Most leading Hindi journals carry his critical essays on politics, education, caste, communalism, violence, Dalit issues and human rights. An avowed secularist, he also writes in English and is known for his frequent interventions in day-to-day politics, and for being a tireless champion of minority rights. He is one of the most vocal critics of the Sangh Parivar in the Hindi belt. Apoorvanand is also biting in his comments on Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and has been very vocal in calling for Gujarat’s ‘mass murderers’ of 2002 to be brought to book.

Columnist Apoorvanand Jha, who mostly prefers to use his first name, is a scholar of Marxian aesthetics. He is a committed Leftist who holds sway over his readers with his incisive and sharp commentaries on the Indian right and corporate interests, besides his write- ups on Indian culture and society. He is simply the most widely read Leftist writer in North India. Scholars, journalists and people opposed to rightwing politics are under the spell of this Delhi University professor, who was born and raised in Siwan, Bihar. A PhD from Patna University, he has also played a significant role in setting syllabii for students, especially in redesigning the academic programme of the Hindi department at Delhi University. Most leading Hindi journals carry his critical essays on politics, education, caste, communalism, violence, Dalit issues and human rights. An avowed secularist, he also writes in English and is known for his frequent interventions in day-to-day politics, and for being a tireless champion of minority rights. He is one of the most vocal critics of the Sangh Parivar in the Hindi belt. Apoorvanand is also biting in his comments on Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and has been very vocal in calling for Gujarat’s ‘mass murderers’ of 2002 to be brought to book.

THE PAST IS NOT ANOTHER COUNTRY: Nayanjot Lahiri, Archaeologist and Cultural Historian, 55

Nayanjot Lahiri, a faculty member of Delhi University, is reckoned to be one of India’s most important contemporary archaeologists—a reason she was awarded the Infosys Prize for Humanities in 2013. Her research spans a spectrum beginning with ancient inscriptions in Assam to trade routes in India before 200 BC. Lahiri is also a historian of Indian archaeology. Her study of the Indus Valley Civilisation has helped us understand that period through aspects like trade and metals. She has edited a volume on its extinction, The Decline and Fall of the Indus Civilization, and also written a book on the civilisation’s discovery, Finding Forgotten Cities. A biography of Emperor Ashoka, due later this year, is eagerly awaited. Lahiri is also a cultural commentator, frequently voicing her opinion in the media on issues related to history and heritage.

Nayanjot Lahiri, a faculty member of Delhi University, is reckoned to be one of India’s most important contemporary archaeologists—a reason she was awarded the Infosys Prize for Humanities in 2013. Her research spans a spectrum beginning with ancient inscriptions in Assam to trade routes in India before 200 BC. Lahiri is also a historian of Indian archaeology. Her study of the Indus Valley Civilisation has helped us understand that period through aspects like trade and metals. She has edited a volume on its extinction, The Decline and Fall of the Indus Civilization, and also written a book on the civilisation’s discovery, Finding Forgotten Cities. A biography of Emperor Ashoka, due later this year, is eagerly awaited. Lahiri is also a cultural commentator, frequently voicing her opinion in the media on issues related to history and heritage.

THE VIGILANTE: Lawrence Liang, Free Speech Activist and Lawyer, 40

The thought police are everywhere these days, turning hyper- sensitivity into hate. Book-burning mobs run rampage, sacrificing a healthy and vibrant society to the degenerative disease of censor ship. Lawrence Liang, a copyright lawyer and co-founder of the Alternative Law Forum, refuses to be a bystander. Liang is a proponent of free speech, especially in the context of the internet and its marketplace of ideas. From sending a legal notice on behalf of aggrieved readers denied access to Wendy Doniger’s book, to making a case for thoughtful jurisprudence in an age when every phone user is a potential writer or publisher, Liang presents compelling arguments for liberal thought without the moral grandstanding of social glory-hounds. Even as India celebrates the fall of Section 66A, the censorship debate rages on, and we can expect Liang to weigh in at every turn.

The thought police are everywhere these days, turning hyper- sensitivity into hate. Book-burning mobs run rampage, sacrificing a healthy and vibrant society to the degenerative disease of censor ship. Lawrence Liang, a copyright lawyer and co-founder of the Alternative Law Forum, refuses to be a bystander. Liang is a proponent of free speech, especially in the context of the internet and its marketplace of ideas. From sending a legal notice on behalf of aggrieved readers denied access to Wendy Doniger’s book, to making a case for thoughtful jurisprudence in an age when every phone user is a potential writer or publisher, Liang presents compelling arguments for liberal thought without the moral grandstanding of social glory-hounds. Even as India celebrates the fall of Section 66A, the censorship debate rages on, and we can expect Liang to weigh in at every turn.

THE EVANGELIST: Mohandas Pai, Educationist and Philanthropist, 55

The former Infosys CFO now runs the largest non-governmental mid-day meal initiative in the country, the Akshaya Patra Foundation. A proud Konkani and Bangalorean, the chairman of Manipal Global Education, and a technology evangelist, Pai wears his heart on his sleeve both on Twitter, the stomping ground of the opinionated, and off it. A champion of civic issues, he has helped shape the debate on good governance with the Bangalore Political Action Committee, a forum he runs with Biocon’s Kiran Mazumdar Shaw. But perhaps what sets him apart is his audacity to take sides—he offered issue-based support to Modi ahead of the 2014 General Election, back when he was still a polarising figure—and stick his neck out of the corporate ivory tower despite being needled for blowing hard on unrelated issues.

The former Infosys CFO now runs the largest non-governmental mid-day meal initiative in the country, the Akshaya Patra Foundation. A proud Konkani and Bangalorean, the chairman of Manipal Global Education, and a technology evangelist, Pai wears his heart on his sleeve both on Twitter, the stomping ground of the opinionated, and off it. A champion of civic issues, he has helped shape the debate on good governance with the Bangalore Political Action Committee, a forum he runs with Biocon’s Kiran Mazumdar Shaw. But perhaps what sets him apart is his audacity to take sides—he offered issue-based support to Modi ahead of the 2014 General Election, back when he was still a polarising figure—and stick his neck out of the corporate ivory tower despite being needled for blowing hard on unrelated issues.

ALL HEART: Devi Shetty, Cardiologist, 61

Healthcare is going to remain one of the biggest concerns for the Indian state in the foreseeable future, and if not for people like Dr Devi Shetty, the ailing poor would be at the mercy of unreliable government health infrastructure. Shetty, who is chairman of Narayana Hrudayalaya, which comprises multi- speciality and super-speciality hospitals, has made healthcare affordable through economies of scale: the higher the volume of surgeries conducted, the lower the cost-per-operation becomes. A profile of him in The Wall Street Journal called Shetty the ‘Henry Ford of Heart Surgery’. His vision for Narayana Hrudayalaya becoming the lowest cost healthcare service provider in the world— without compromising on quality—is getting translated into reality. Starting from Bangalore, his hospitals have fanned across the country now.

Healthcare is going to remain one of the biggest concerns for the Indian state in the foreseeable future, and if not for people like Dr Devi Shetty, the ailing poor would be at the mercy of unreliable government health infrastructure. Shetty, who is chairman of Narayana Hrudayalaya, which comprises multi- speciality and super-speciality hospitals, has made healthcare affordable through economies of scale: the higher the volume of surgeries conducted, the lower the cost-per-operation becomes. A profile of him in The Wall Street Journal called Shetty the ‘Henry Ford of Heart Surgery’. His vision for Narayana Hrudayalaya becoming the lowest cost healthcare service provider in the world— without compromising on quality—is getting translated into reality. Starting from Bangalore, his hospitals have fanned across the country now.

THE MESSENGER: Piyush Pandey, Advertising Professional, 60

He massages his famed moustache while reeling out his favourite catchphrases as if he is on a testosterone overdrive. He was on overdrive last year, literally, sleeping very few hours and churning out slogans for the BJP, which went on to win the General Election. His most famous was the potent ‘Abki baar Modi sarkar’, a catchy line in Hindi which proved an instant hit. It went viral and the coherence of the overall BJP ad campaign perhaps foretold Narendra Modi’s decisive win. It was for the first time that Pandey had taken a plunge into political campaigning, because his employer, Ogilvy, once feared that politicians never pay. Pandey and his team came up with 125 artworks across TV, radio and print, every single night during the two months of the most high-wattage electoral campaign ever seen in India. With Modi’s win, Pandey also proved that he was adept at responding quickly—he launched a commercial, ‘Kamal par button dabao’ right after complaints arose that rivals were using Modi’s name to misinform illiterate voters that his symbol was the cycle, elephant or some such.

He massages his famed moustache while reeling out his favourite catchphrases as if he is on a testosterone overdrive. He was on overdrive last year, literally, sleeping very few hours and churning out slogans for the BJP, which went on to win the General Election. His most famous was the potent ‘Abki baar Modi sarkar’, a catchy line in Hindi which proved an instant hit. It went viral and the coherence of the overall BJP ad campaign perhaps foretold Narendra Modi’s decisive win. It was for the first time that Pandey had taken a plunge into political campaigning, because his employer, Ogilvy, once feared that politicians never pay. Pandey and his team came up with 125 artworks across TV, radio and print, every single night during the two months of the most high-wattage electoral campaign ever seen in India. With Modi’s win, Pandey also proved that he was adept at responding quickly—he launched a commercial, ‘Kamal par button dabao’ right after complaints arose that rivals were using Modi’s name to misinform illiterate voters that his symbol was the cycle, elephant or some such.

THE UPLIFTER: Chandra Bhan Prasad, Social Pyschologist, 45

If Ambedkar exhorted Dalits to move to urban India to escape the travails of caste, Chandra Bhan Prasad wants them to turn entrepreneurs and job-creators in a globalised world. He has chronicled the journeys of 21 such Dalits in a book that makes a strong case for economic change as a necessary condition for social and political empowerment. Prasad advances the argument that Dalits ought to succeed in manufacturing as Indian elites turn to the air-conditioned comfort of the service sector. An English education, he insists, is key to the democratisation of knowledge. He should know. A rare Dalit columnist writing in the mainstream media, Prasad has emerged as an important commentator with a rebellious streak as he steers clear of platitudes on the Dalit struggle, dismisses the idea that the politics of Mayawati or other Dalit leaders has empowered the oppressed, and advocates a modern outlook.

If Ambedkar exhorted Dalits to move to urban India to escape the travails of caste, Chandra Bhan Prasad wants them to turn entrepreneurs and job-creators in a globalised world. He has chronicled the journeys of 21 such Dalits in a book that makes a strong case for economic change as a necessary condition for social and political empowerment. Prasad advances the argument that Dalits ought to succeed in manufacturing as Indian elites turn to the air-conditioned comfort of the service sector. An English education, he insists, is key to the democratisation of knowledge. He should know. A rare Dalit columnist writing in the mainstream media, Prasad has emerged as an important commentator with a rebellious streak as he steers clear of platitudes on the Dalit struggle, dismisses the idea that the politics of Mayawati or other Dalit leaders has empowered the oppressed, and advocates a modern outlook.

POSTER GIRL OF THE WRETCHED: Arundhati Roy, Writer and Activist, 53

She may be a lapsed celebrity back home, ruing from the fringes the death of radical thought at the bloody tooth- and-claw of Capital. But a certain kind of Western audience has not wearied of her indignation since The God of Small Things. She has been hailed as the ‘goddess of rebellion’, a left-of-left outsider-insider expressing her pique at all that’s wrong with India. In a characteristic attack on corporate capitalism that went viral, she rails against ‘turning potential revolutionaries into salaried activists’ and rejects discourse ‘couched in the language of identity politics and human rights’. Roy, it must be said, knows how to drive a point home. That cannot be said, however, for the volley of allegations she levels at everyone from Gandhi to Mandela with the cyclic routine of Deepak Chopra releases, often eliciting little more than mockery.

She may be a lapsed celebrity back home, ruing from the fringes the death of radical thought at the bloody tooth- and-claw of Capital. But a certain kind of Western audience has not wearied of her indignation since The God of Small Things. She has been hailed as the ‘goddess of rebellion’, a left-of-left outsider-insider expressing her pique at all that’s wrong with India. In a characteristic attack on corporate capitalism that went viral, she rails against ‘turning potential revolutionaries into salaried activists’ and rejects discourse ‘couched in the language of identity politics and human rights’. Roy, it must be said, knows how to drive a point home. That cannot be said, however, for the volley of allegations she levels at everyone from Gandhi to Mandela with the cyclic routine of Deepak Chopra releases, often eliciting little more than mockery.

PULP PULPIT: Chetan Bhagat, Writer, 41

In intellectual circles, Chetan Bhagat has been relegated to the category of pulp fiction writers. But it is the peculiar nature of Indian society that Bhagat is actually counted as ‘an intellectual’ by a large number of people. Here is a man who writes racy formulaic novels using tropes that ring a bell with young people. A newspaper columnist, he is invited to appear on TV news channels for discussions that range from AAP to the state of Indian education. Movies based on his books are made by the best filmmakers of India with top superstars, and they rake in tens of crore. And he is now a judge on a reality TV dance show. Bhagat is impossible to ignore, and even those who have disdain for him admit as much. He might be ready with an opinion on everything, but it’s one that’s heard.

In intellectual circles, Chetan Bhagat has been relegated to the category of pulp fiction writers. But it is the peculiar nature of Indian society that Bhagat is actually counted as ‘an intellectual’ by a large number of people. Here is a man who writes racy formulaic novels using tropes that ring a bell with young people. A newspaper columnist, he is invited to appear on TV news channels for discussions that range from AAP to the state of Indian education. Movies based on his books are made by the best filmmakers of India with top superstars, and they rake in tens of crore. And he is now a judge on a reality TV dance show. Bhagat is impossible to ignore, and even those who have disdain for him admit as much. He might be ready with an opinion on everything, but it’s one that’s heard.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

‘We Have Instilled Fear of the Law in Drug Syndicates,’ says Amit Shah

MOst Popular

4

/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Cover_Amit-Shah.jpg)

More Columns

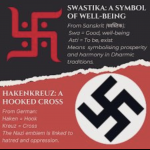

Elon Musk attracts sharp attack over ‘swastika’ from Indians on social media Ullekh NP

Yunus and the case of a "land locked" imagination Siddharth Singh

Why CSK Fans Are Angry With ‘Thala’ Dhoni Short Post