Father, Son and the Double Helix

Suspicious couples and the booming cottage industry of peace-of-mind tests

Snigdha Poonam

Snigdha Poonam

Snigdha Poonam

Snigdha Poonam

|

21 Jan, 2015

|

21 Jan, 2015

/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/17528.fatherson1.jpg)

“I hope you’ve been told about the birds and the bees,” said KS Mehta, visibly concerned about my ability to grasp the complicated things sex can lead to. We were sitting in his DNA testing centre in south Delhi and I had asked him for backstories of the many paternity tests he had facilitated so far. We had already gone over the crucial matter of my age and marital status (“You’re not married, right? I can tell.”). What he dealt in were some very adult matters, he stressed, sliding a plate of biscuits in my direction. Looking over us from the wall behind Mehta, a heavy- set Sikh in his fifties who also heads the Computer Science department at Lovely University, Jalandhar, was a large watercolour painting of a horse in flight; EL James’ entire series of Fifty Shades stood out in the bottom row of his wall-length bookshelf on the left. His was also a very risky job, Mehta told me later in our conversation, often placing him in the middle of family confrontations verging on a bloodbath. “Just a few weeks ago, I had the families of a Muslim couple on either side going at each other in my office. The man had been nurturing the doubt that two of the couple’s five children were not his, and had dragged his wife to Delhi to resolve the matter through a DNA test. He had samples of all his five children tested against his own. The whole family rented a hotel near Jama Masjid and remained there until we gave them the results, which is when all hell broke out.” A steady majority of requests for paternity tests his clinic got was from couples living in joint families, where, Mehta elucidated, the uncertainty over a child’s parentage tends to be high. “There are so many men and women in a family. You can never tell a child’s parentage for sure.” More fights broke out in his office over positive results than over negative ones; the doubting men almost always reacted badly to being proven wrong. “Usually DNA results don’t turn out to be what you want them to be. Like with this Muslim guy, who, on finding out that he had fathered them all, first attacked me for having gotten the results wrong, and when I told him he could get the test done in any other DNA lab at my expense, went for his wife, berating her for having failed to convince him that the children were all his own.”

Since 2008, when Mehta set up Indian Biosciences, the Indian subsidiary of the American laboratory DNA Diagnostics Centre, one of the world’s largest providers of DNA tests, he claims to have seen it all. Over the time that he’s been in this business, a dozen private DNA testing labs have come up in major Indian cities with networks of collection centres all over the country. Regional newspapers report the cropping up of small-time paternity test clinics in less populous cities and towns as well, attributing the phenomenon to the repeated appearance of the practice on TV in popular Indian soap operas. Lending the idea further credence is last year’s Supreme Court ruling that prioritised paternity tests as a move in establishing infidelity during divorce proceedings. It went against the Judiciary’s long-held view that the genetic parentage of a child born of a legal union or within 40 weeks of a marriage’s dissolution stood above doubt. A news report from Gujarat in December put court-sanctioned paternity tests conducted in the state at an annual average of 250, most of them done to settle a matter of divorce or inheritance. The data studied by the state’s Directorate of Forensic Sciences showed that 98 per cent of the cases were to ‘confirm suspicions’. More men from rural areas than urban centres had requested courts to order paternity tests.

Nothing, however, has done more to mainstream the idea of paternity testing than the dramatic court case involving the senior Congress leader ND Tiwari and a 28-year-old man who claimed to be his biological son, Rohit Shekhar. In 2008, Shekhar approached the Delhi High Court claiming his right to be accepted as the son of Tiwari, who had had a long and well-known affair with his mother, Ujjwala Sharma, but wouldn’t accept her son as his own. In 2012, after an interminable legal tug of war, Tiwari was ordered by the Supreme Court to submit his DNA sample for a paternity test. It vindicated Shekhar and led to a gradual reunion of the whole family, ending in the marriage of Tiwari, 88 years of age, and Sharma, 62, in May 2014.

Easy DNA, a laboratory based in the town of Nagarcoil in Tamil Nadu, deals with 30 cases of paternity tests a month, said Rama Anandi, who works in its marketing division. Most requests for paternity tests at Easy DNA are spurred by “husbands having doubts on wives”. The DNA samples and results are generally sent across via mail and the payments made online. All a client has to do is buy a home test kit, take a saliva swab of the child’s mouth, and mail the samples to the nearest collection centre. The results are sent back in no more than two weeks. “This is a sensitive issue for a family, so we have to maintain 100 per cent confidentiality, that’s why things work out better through post,” says Anandi over the phone. The lab also gets requests from hospitals for ‘maternity tests’ to resolve the tricky cases of infants mixed up by hospital staff or caught up in a suspected ‘child swap’, where male children are stolen from hospitals by organised networks of child thieves and replaced by female infants.

“Sometimes it’s the mothers themselves, who, especially if they have already given birth to girls and are under pressure from their families, bribe the hospital staff to swap their female child with a male child,” discloses Dr N.K. Mehra, former Dean of Research at AIIMS. The trickiest case of a child swap he has dealt with was also one that became a primetime sensation. “In the late 80s, I came to India from the US at the request of the Delhi Police, who were facing incredible pressure to solve a child swap case in Safdarjung Hospital that was all over the media,” he says. Five couples had had babies in the hospital on the same day, four of them had died, and the only one alive, a girl child, was being turned down by the supposed mother, who claimed she remembered feeding a male baby before it was taken from her by the staff for a clean- up. “This was double trouble. Where was her child, then, and who did the baby girl belong to? The police brought up the remaining four couples and I took all their DNA samples. But meanwhile, the police was in a hurry to close the publicised case so they brought a male baby found at a railway crossing and gave it to the mother saying that must be her missing son. Before I could present the results of the paternity and maternity tests, the mother had accepted the boy as her own, even persuading me to believe that the newborn’s nose was just like her husband’s.” Dr Mehra, how ever, carried on with the investigations and what emerged at the end of it was bewildering. “We dug up the remains of the four dead children. It turned out that the lady’s son was amongst the dead, and the baby girl belonged to one of four couples who had gone back to their village and observed every ritual of mourning for the dead child. The woman who had lost the son decided to keep the baby from the railway track and raise it as her own.”

In the 1980s, Dr Mehra says, he worked on many cases of Thalassaemia, a genetically inherited blood disorder common in India, and every once in a while he would come upon cases where a child’s DNA didn’t match the father’s. “Then, as now, it was always a social reason at its root. The condition is passed down if both the parents are carriers, but only the woman is blamed by the family for giving birth to a child with a defect. What many women did, therefore, after giving birth to a child born with the condition, was to conceive their next child with a man other than the father, a non-carrier. We would become aware of this while genetically testing the family before treating any one of them. I would sometimes tell the women about the mismatched results, but they always requested me to keep it to myself.”

It’s only the paternity tests to be submitted to a court that need to process the mother’s sample, but sometimes even a common ‘peace of mind’ test can be impossible to resolve without bringing in the mother. Mehta faced one recently at Indian Biosciences. “I had a client who worked in the merchant navy and was away most of the time. While he was on a year-long work trip, his wife tells him she’s pregnant. The child is born by the time he’s back, but he has a doubt. He comes to us with the DNA samples, and it turns out that he is not the father. He makes his wife go through a maternity test, and we find out she’s not the mother either,” says Mehta, a twinkle in his eyes betraying a fondness of such mysteries. “I spoke to the lady, I spoke to her for a long time. Finally, she reveals that she had found that she couldn’t be a mother but feared the marriage would collapse because of this. So she asked her pregnant sister to give her the child to save her marriage. In the end, all was well as the man accepted the child and they’re living happily as a family now.”

Indeed the advent of instant-noodle- style paternity tests has been seen by some feminists globally as a setback to the balance of power between the sexes, as an ‘anti-feminist’ use of science. ‘A woman’s prerogative of knowing her child’s father was the trump card of sex. It accounted for the vice of jealousy in men; it made a mockery of the laws of inheritance; it made claims to omni potence absurd,’ argued the feminist Melanie McDonagh in The Times in 2010, shortly after a series of overly publicised cases in the UK of rich men seeking the stamp of a DNA testing lab before continuing to support the children they had until then believed to be their own. ‘Scientific certainty has produced clarity all right, and relieved any number of men of their moral obligations, but at God knows what cost in misery, recrimination and guilt,’ she wrote.

That isn’t, however, the only reasonable point of view on this ethically convoluted subject. Others have held up the new accessibility of paternity tests as an improvement on the time when a man could claim a child to be someone else’s and a woman had no way to validate her claim. And there are those who argue that instead of fighting over whether paternity tests are good or bad news for women, one should work towards a world where not having a father does not disadvantage a child in any way.

In India, most private clinics came up to cater to a market gap opened up by DNA testing becoming central to immigration and surrogacy, but their proprietors would tell you that the rise in casual sex and ubiquity of live-in relationships have created a new burst of demand. “There are girls who come to us after they have missed a period and they want to know whose child it is before deciding [whether] to go ahead with the pregnancy, so we end up doing a lot of pre-natal tests,” says Mehta, “They are becoming as common as post-natal paternity tests. It’s a big area. Earlier it was an invasive procedure involving the drawing of a little fluid from a woman’s womb, but now a test can be done by using the mother’s blood after eight weeks of pregnancy.”

The rate cards of private DNA testing centres are a minor study in the anxieties of a changing society. A personal ‘paternity Test with no maternal involvement’ would cost Rs 10,000, whereas a ‘legal Paternity Test with maternal involvement’ could set one back by Rs 40,000. Also on offer are services termed ‘sibling relationship test’, a common way to resolve inheritance feuds within large families, or an ‘infidelity test’. “In a recent ‘infidelity test’ we conducted at our clinic, a married woman who had been away in the US came back to find a strand of hair on the couple’s bed that didn’t seem to be hers, so she came to us with the hair, and it turned out that it indeed belonged to someone else,” says Mehta. “We ask people to bring us any telling sample they can find—underwear, a used condom…”

For Ritu Sohaney, proprietor of One Touch Solutions, a DNA testing centre in Hyderabad, the widening social embrace of the paternity test is another outcome of “the new metropolitan life”. “The rise of doubt in the mind of the husband is inevitable, and the ‘peace of mind test’ is the only way to settle it conclusively,” says Sohaney. Since she set up the Indian branch of the US-based laboratory five years ago, she claims to have dealt with hundreds of request from all over the country.

Indeed, DNA lab owners aren’t the only ones making money off this Indian paranoia about the rumoured collapse of sexual monogamy. Dozens of detective agencies are cropping up across Indian cities every day to investigate cases of ‘cheating partners’; and it’s possible to find a marriage counsellor with a simple internet search. “I deal with three or four clients every day, and many of the cases are about infidelity. I come across women who have seven-seven, eight-eight affairs at one time,” says Nisha Khanna, a Gurgaon-based marriage counsellor who deals only with the “NCR’s elite”. “I mostly counsel couples who have been married for 10-12 years and have reached a phase where they have started to question the meaning of the relationship.”

In Khanna’s experience, women tend to have less patience with working on a marriage than men. “In most of the cases where they are going for relationships outside marriage, men are forgiving of their wives. They decide to remain silent for the sake of the kids or society,” says Khanna, who seems to have judged the rich men and women on moral strength and found the latter wanting. Men and women are equally eager to put their partner through a lie detector test to settle the issue of loyalty, however, she reveals. “I have someone walk in every one in three days who wants to subject his or her partner to the test to establish sexual loyalty, the lie detector test being available in some forensic labs for Rs 15,000, but my advice to them is not to give in to the instinct.”

The business of casual paternity testing, argues Ms Khanna, is another way to encourage people to be suspicious all the time. “A partner may or may not be unfaithful, but going for a test to deal with your doubts will ruin the relationship forever.” And so continues the debate between scientific certainty and psychic insecurity.

(Snigdha Poonam is a freelance journalist based in Delhi)

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

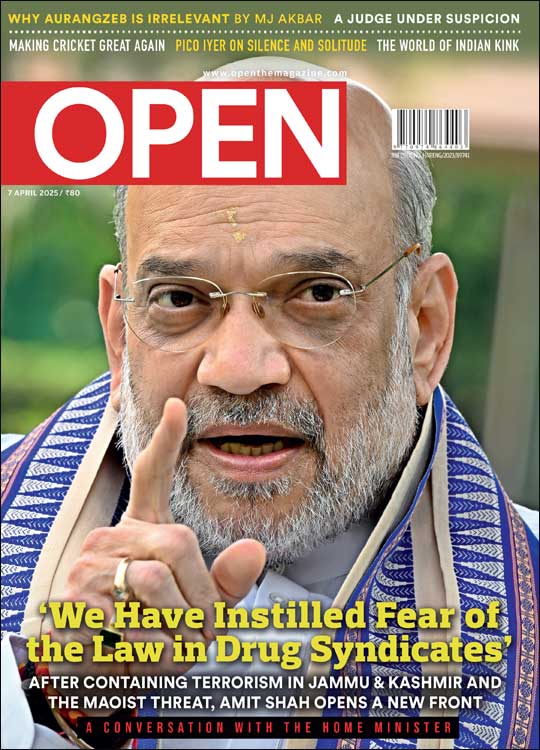

‘We Have Instilled Fear of the Law in Drug Syndicates,’ says Amit Shah

MOst Popular

4

/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Cover_Amit-Shah.jpg)

More Columns

Why CSK Fans Are Angry With ‘Thala’ Dhoni Short Post

What’s Wrong With Brazil? Sudeep Paul

A Freebie With Limitations Madhavankutty Pillai