Resizing Osama bin Laden

On the first death anniversary of the world’s most wanted man this century, it is time we asked whether his menace was blown completely out of proportion

Abhijnan Rej

Abhijnan Rej

Abhijnan Rej

|

27 Apr, 2012

Abhijnan Rej

|

27 Apr, 2012

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/osama1.jpg)

On the first death anniversary of the world’s most wanted man this century, it is time to ask if his menace was blown out of proportion

Early in the days and months after 9/11, a senior Norwegian diplomat Espen Eide, following his peacekeeping experiences in the Balkans, called Osama bin Laden a “conflict entrepreneur”. The New York Times ran long pieces on the organisational structure of Al-Qaida, depicting it as a well-managed modern multinational company with bin Laden as its CEO. President Bush evoked the Wild West with a ‘Wanted Dead or Alive’ slogan, unwittingly equating bin Laden with Jesse James. French philosophers being French philosophers spoke of Al-Qaida’s (and ergo bin Laden’s) actions as spectacular works of theatre whose aim was to ‘radicalise the world by sacrifice’. In the Indian state of West Bengal, a leading member of the (then ruling) Communist Party sympathised with the attack on the Pentagon; after all, he rationalised to disbelieving members of the press, wasn’t ‘Pentagone kaman dago’ (‘Take aim at the Pentagon’) one of the Communist Party’s early slogans? Badly printed Che-type T-shirts with bin Laden on it sold like hot kebabs in the not-so-tony neighbourhoods of Islamabad and Karachi which young men wore with pride, sipping on a local version of Coca-Cola. The good Reverend Jerry Falwell went above and beyond everyone else by indirectly claiming that bin Laden was actually doing God’s job by punishing America for allowing “alternative lifestyles”.

From Berlin to Bombay, from Georgetown to Jakarta, Osama bin Mohammed bin Awad bin Laden became whatever people wanted him to be, a bit like a certain class of high-priced ‘escorts’ one sees advertised in the ‘Personal’ columns of adult magazines.

Two wars later and one year ago, Osama bin Laden was executed by the US government in the most banal of circumstances in Abbottabad, Pakistan—cooped up in a house full with wives, children and, apparently, domestic intrigue. All it took was less than a handful of bullets from a HK416 rifle and virtually no real resistance to end the life of a man with an image much larger than the sum of his actual misdeeds. The real Slim Shady finally stood up, or more accurately, was laid to rest in the Arabian Sea. In fact, the lack of resistance on bin Laden’s part was so great that soon after the Abottabad operation on 2 May 2011, a section of the American administration first spoke of a “fierce gunfight” and then quietly went on to concede a few days later that it was, certainly by the standards of US Navy Seals, a rather tame affair.

The utter triviality of the operation, the lack of resistance from bin Laden’s side, and even its venue—more suited to landed Pakistani gentry than a terrorist mastermind with a $25 million bounty on his head—confirmed the proposition once and for all that for a larger part of the past decade, we have systematically overrated Osama bin Laden. The truth is that he was just another Salafi fanatic and self-styled emir-cum-saviour who just happened to ‘luck out’ through a chain of accidental encounters that inadvertently made him the poster boy of violent and suicidal Islamist radicalism. He was neither a James Bond style villain living in an air-conditioned cave-turned-bunker (as the then US Defense Secretary would have us believe), nor an Adolf Hitler mobilising and directly addressing millions of people together. He was not a ‘conflict entrepreneur’; as far as one can tell, money for him was always on a one-way street out. Neither was Al-Qaida a coherent centralised organisation like, say, the Baader-Meinhof gang of the 1970s. (One of the suspects interrogated in the aftermath of the 1998 bombing of American Embassies in Africa was unconsciously very accurate when he described Al-Qaida as a “formula system”, “a tactic not an entity” [1].) Even more telling, the Muslim world (in the throes of the Arab Spring) appeared markedly indifferent to the news of bin Laden’s execution, showing yet again that he was not what he implicitly claimed to be in his many poorly-made home videos: the voice of Muslims, humiliated and oppressed.

The question then is this: how did a shy and rather effete civil engineer from a wealthy Saudi family without any military or political training, albeit with extreme religious beliefs, end up being such an über-monster-figure that intelligence analysts and the average Joe alike were led to build such grand narratives around him? Why did we give him ‘an air-conditioned multi-layered bunker’ and imagine him to be the central controller of mostly imaginary sleeper-cells all around the world ready to activate weapons of mass destruction at his first call? Plainly put, what made us so damn afraid of him?

In the intervening decade, many seemingly convincing answers to these questions have been proposed. The one I am suggesting here is through the eyes of a specialist in complex systems theory. As this theory tells us, given a question about the evolution of an entity (humans, ant colonies, autonomous machines, you name it), the answer always starts with an analysis of the terrain in which the entity is embedded. In Osama bin Laden’s case, it was Afghanistan, which was already, post-Soviet invasion, a cat’s cradle of mujahideen groups competing (and often in-fighting) for the guns, ammunition and most importantly money flowing in from the Saudi government and later from the US. Each country had its own reasons for this oft-unaccounted-for largesse: Saudi Arabia was still smarting over the 1979 occupation of the Grand Mosque in Mecca by an extreme Wahhabi faction, and coupled with the Shia revolution in Iran that very year, keen to establish to the wider world that: (a) they were still in control of the majority Sunni Islam (the Grand Mosque incident aside), and, as a logical extension (b) it was they who were the vanguards of true Islam that would stand by oppressed Muslims all over the world [2]. The United States, largely pushed by a single enterprising and unlikely Congressman from Texas, Charlie ‘Good Time’ Wilson, saw Afghanistan a part of the Great Cold War Game, so much so that on paper the US government forbade the CIA or Special Operations forces to even set foot in Afghanistan lest it led to a wider US-Soviet conflagration.

Various accounts of the time point to a confused humdrum where large amounts of weaponry, foreign and domestic mujahideen fighters, curious hangers-on, freeloaders and intelligence specialists from Pakistan in charge of disbursing American money (often literally filling Pakistani military transport jets with $100 bills) to various anti-Soviet groups all operated at the edge of chaos. The only goal that was common to all of them was protecting their own personal interests as firmly as they could. This was the high-octane mess in which men like bin Laden, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, Ahmed Shah Massoud and Jalaluddin Haqqani found their professional foot and, more prosaically, a fertile ground for recruitment for their yet-to-be-specified missions. In all this, there were no obvious signs that made the reticent lanky Saudi, almost exclusively in charge back then of disbursing dollars and riyals to the fighters, their families and the injured, stand out in the crowd.

In fact, if I were to time-travel to the early 80s’ Afghanistan, I would have bet on fiery and feisty men like Jalaluddin Haqqani, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar or Ahmed Shah Massoud to be the eventual headaches, not Osama bin Laden. (The last was ditched by the US before he could ditch it, the second is an unpredictable opportunist, and the first is currently an unending full-blown migraine.) At his best, bin Laden was primus inter pares, the first among equals, as Jason Burke call him in his authoritative book Al-Qaeda. (Burke was most probably referring to bin Laden’s considerable skills as a fundraiser and not his war-fighting abilities.)

In a complex system, the terrain often exclusively determines the trajectory of the entity in question, and in bin Laden’s case, it was not any different—he eventually became who he became out of sheer luck and through a socio-physical phenomenon called ‘mode-locking’. Made very popular in the complex systems community by the economist Brian Arthur [3], mode-locking is, simply put, a phenomenon that starts by chance and because of its character keeps growing and growing, whereas a similar phenomenon with equal potential remains dormant simply because it wasn’t lucky the first time.

As a high-school student, I once had a summer job with an economist who was studying a seemingly frivolous problem, namely, why is it that a certain football club in the Norwegian league kept winning every session? (Norwegian sports monopoly laws seemed to have a problem with this.) Resisting my obvious “Well, they play better” answer, my mentor came up with a very interesting explanation. Suppose this club X won, say, completely by chance the first time. With the prize money, they’d buy better players for the next session, which would improve their odds of winning. With a bit of luck and ever better players, club X will be the best team in the league, and ergo, invincible. We would say, “Club X became mode-locked to winning.”

Arthur has used this principle, first observed in lasers and electronic circuits, to great success in economics, including explaining mysteries such as why we preferred VHS video cassettes to Betamax back when we actually used to use such things. I believe mode-locking was also what the complexity theorist Doyne Farmer had in mind when he explained bin Laden’s ‘successes’ as ‘pure luck’.

Put together in a simple package, Osama bin Laden became what he was not because he was a better fighter or commanded better weaponry or even a competent theologian like Sheikh Omar Rehman, but simply because he was mode-locked to success by a series of random events, each reinforcing the next.

First, Osama bin Laden was lucky to have Ayman al Zawahiri by his side. By all accounts, al Zawahiri came to bin Laden for his money, and in return, al Zawahiri—already a skilled saboteur and organiser implicated in the assassination of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat—led the Egyptian volunteers who gave bin Laden his early main muscle. (This is not to say that the relationship between al Zawahiri and bin Laden was not without mutual suspicion; at one point, as Lawrence Wright tells the story [4], faced with ‘the formidable task of infiltrating the American intelligence’, al Zawahiri’s man offered to rat bin Laden out, location maps of camps and all, to the FBI and members of the US military intelligence.)

Second, post-Cold War, American intelligence was either not equipped or disinclined to track seemingly harmless intrigues in the Middle East or North Africa that did not pertain to Israel and Palestine; their half-hearted attitude gave bin Laden the space and time to group and regroup without the penetrating gaze of US intelligence. (One of the strategic disasters around that time was the US decision to close down intelligence gathering activities in Afghanistan in 1991 [5])

Third, and this is a point that is often not noted as strongly as it should be, bin Laden got Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM), a man with a personal life and beliefs perpendicular to his own, to join his ‘company’, to use the surprisingly crude code of Al-Qaida [6]. Again in the random life of Osama bin Laden, it was KSM who sought him out after KSM’s nephew Ramzi Yousef had been implicated in the first bombing of New York’s World Trade Center in 1993, bin Laden’s first idée fixe. Back in Quetta, Pakistan and later in the Philippines, Yousef and KSM then planned a spectacular mid-air bombing of ten American passenger jets, bin Laden’s second idée fixe.

Jets and the World Trade Center—both ideas were of the uncle-nephew duo, not of bin Laden, and yet the combination of these two would be forever associated with him. (Such is the rate of misattribution in this game that after Yousef’s plot to assassinate Benazir Bhutto surfaced, she went around claiming that bin Laden was trying to kill her; indeed, in Pakistan today after Bhutto’s actual assassination, the ‘bin Laden hand’ is a prevalent school of thought particularly popular with the military.)

The hatred that KSM bore the US had dimensions that were personal—his stay in the US as a student of a C-college was marked by brief detentions due to unpaid bills and suchlike—as well as communal, such as America’s Israel policy. A formidable terrorist planner, it was he and not bin Laden who should be held as (and going by America’s 9/11 Commission Report is) the ‘principal architect’ of 9/11. KSM moved the money around South Asia and then on to the US [7], helped facilitate the travel of the 19 hijackers and co-chose the targets. As a matter of fact, reports indicate many vocal differences between bin Laden and KSM about the details and mode of execution, a far cry from bin Laden as ‘Herr Fuhrer’ whose decisions were the final word. Indeed, reading and re-reading various accounts of what actually transpired during that planning period, it might not be too inappropriate to describe bin Laden as a kind of elderly aunt whose blessings are sought before taking any major decision but not before setting something in motion.

Tactical and strategic abilities aside, even as a global theorist of radical Islamism, bin Laden was not a pioneer. It was, in fact, a Syrian-Spaniard with the nom de guerre Abu Mus’ab al Suri, who first outlined with some detail in 1991 a doctrine of ‘Global Islamic Resistance’ that would later become Al-Qaida’s blueprint of action [8], some five years before bin Laden’s famous fatwa, which, incidentally, seemed to have been authored by al Zawahiri. Over the years, bin Laden would go on to recycle al Suri’s writings at various occasions both private and public, vacillating between causes and often peppering it with bad poetry.

At the end, for bin Laden, the greatest piece of luck came in the form of Mohammed Atta, a highly disciplined and emotionally opaque architect from Egypt. With KSM at the tactical helm, Atta went on to become the operational leader of the greatest act of terror in history. It is also history’s great irony that what made Atta and others in Al-Qaida’s Hamburg cell so lucky as well was a German society that was, post-World War II, unusually careful about policing foreigners or keeping them under surveillance.

To make a full circle then and return to where we started, it was the material event, the death of almost 3,000 people, that defined Osama bin Laden, not the other way round. When the history of the 21st century is finally written, he will probably be remembered mostly as an epi-phenomenon and nothing more. Reading and re-reading Osama bin Laden’s life story, one is struck not as much by his deviousness but by the sheer luck the man seemed to have been bestowed. Chance encounters, tenuous connections, ‘loose associations’ and ‘just being there at the right place and at the right time’ are all that made a merely dangerous fanatic the most infamous figure of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

At each step of his story, there’s always a coin toss in bin Laden’s favour, much like Rosencrantz’s in Tom Stoppard’s play, and just like Guildenstern, we have always attributed his sheer good luck to everything but itself.

To understand how very lucky this man was, a counterfactual experiment is all that it takes: imagine al Zawahiri never meeting bin Laden; imagine bin Laden dismissing KSM out of hand (as he often did with many enthusiasts); and finally imagine Mohammed Atta—alienated in Hamburg—finding solace in music or women or cinema, rather than suicidal extremism.

Such are the mechanics of a mode-locked destiny.

For the next few days around the first death anniversary of Osama bin Laden on 2 May, round-the-clock news channels all over the world will, almost as an act of journalistic liturgy, run and rerun what we have seen a little too much of already—the burning towers, the half-destroyed aircraft in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, the smoke billowing out of the outer rim of the Pentagon, the rehashed clip of bin Laden firing a Kalashnikov into nowhere, and finally the picture of the White House Situation Room with President Obama in his shirtsleeves, anxiously awaiting a simple phrase: ‘Geronimo E.K.I.A.’ At the end, and after we have seen this all over again, the question that will remain with us is simply this: is this man’s life, so remarkably accidental and therefore so unremarkable, worth so much space in our collective consciousness?

Abhijnan Rej is a member of the faculty at Institute of Mathematics & Applications, Bhubaneswar, a contributing analyst at Wikistrat, Inc’s South Asia Desk, and a researcher with Hybrid Reality Institute

Footnotes:

1 Jason Burke, Al-Qaeda, IB Tauris/Penguin Books, 2003/2007, pg 7.

3 cf. Brian Arthur, Increasing Returns and Path Dependence in the Economy, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 1994: for nice applications to economic problems

4 Lawrence Wright The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda’s Road to 9/11, Penguin, 2006/2011, pg 204).

5 Robert Baer See No Evil: The True Story of a Ground Soldier in the CIA’s War on Terrorism, Crown/ Three Rivers Press, 2001/2003

6 Jason Burke Al-Qaeda, (IB Tauris/Penguin Books, 2003/2007), pg 7

7 cf. Shishir Gupta’s The Indian Mujahideen: The Enemy Within, Hachette India, 2011: for an account of how a part of the money used to fund 9/11 came from the ransom paid by a mid-level businessman from eastern India and how, through various intermediaries, ended up with KSM.

8 Brynjar Lia Architect of Global Jihad: The Life of al-Qaeda Strategist Abu Mus’ab al Suri, Hurst (2009),

pg 6

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

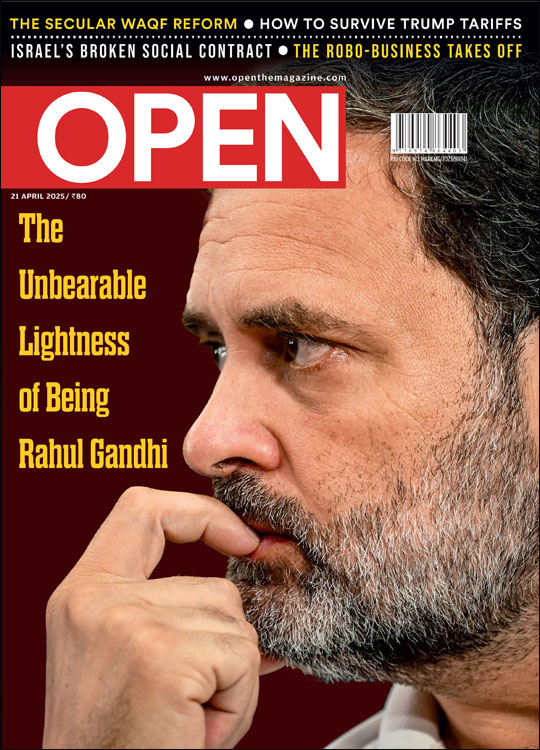

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Rahul Gandhi

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Cover-Congress.jpg)

More Columns

Ukraine silently encroaches on ‘friendly’ Moldova Ullekh NP

NFRA chief Ajay Pandey joins AIIB Rajeev Deshpande

The Revenge of Roughage V Shoba