Left with No Choice

A chilling account of the circumstances under which a Kashmiri Pandit family was forced out of the Valley, the terror that foreclosed all hope of returning, and the grim existence of those who sought shelter in a Jammu refugee camp. Excerpts from Rahul Pandita’s latest book, Our Moon Has Blood Clots

Rahul Pandita

Rahul Pandita

Rahul Pandita

Rahul Pandita

|

16 Jan, 2013

|

16 Jan, 2013

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/blood-clots-1.jpg)

A chilling account of the circumstances under which a Kashmiri Pandit family was forced out of the Valley. Excerpts from Our Moon Has Blood Clots

JANUARY 1990, KASHMIR VALLEY

19 January 1990 was a very cold day despite the sun’s weak attempts to emerge from behind dark clouds. In the afternoon, I played cricket with some boys from my neighbourhood. All of us wore thick sweaters and pherans. I would always remove my pheran and place it on the fence in the kitchen garden. After playing, I would wear it before entering the house to escape my mother’s wrath. She’d worry that I’d catch a cold. “The neighbours will think that I am incapable of taking care of my children,” she would say in exasperation.

We had an early dinner that evening and, since there was no electricity, we couldn’t watch television. Father heard the evening news bulletin on the radio as usual, and just as we were going to sleep, the electricity returned.

I am in a deep slumber. I can hear strange noises. Fear grips me. All is not well. Everything is going to change. I see shadows of men slithering along our compound wall. And then they jump inside. One by one. So many of them.

I woke up startled. But the zero-watt bulb was not on. The hundred-watt bulb was. Father was waking me up. “Something is happening,” he said. I could hear it—there were people out on the streets. They were talking loudly. Some major activity was underfoot. Were they setting our locality on fire?

So, it wasn’t entirely a dream, after all? Will they jump inside now?

Then a whistling sound could be heard. It was the sound of the mosque’s loudspeaker. We heard it every day in the wee hours of the morning just before the muezzin broke into the azaan. But normally the whistle was short-lived; that night, it refused to stop. That night, the muezzin didn’t call. That night, it felt like something sinister was going to happen.

The noise outside our house had died down. But in the mosque, we could hear people’s voices. They were arguing about something.

My uncle’s family came to our side of the house. “What is happening?” Uncle asked. “Something is happening,” Father said. “They are up to something.”

It was then that a long drawl tore through the murmurs, and with the same force, the loudspeaker began to hiss.

“Naara-e-taqbeer, Allah ho Akbar!”

I looked at my father; his face was contorted. He knew only too well what the slogan meant. I had heard it as well, in a stirring drama telecast a few years ago on Doordarshan, an adaptation of Bhisham Sahni’s Tamas, a novel based on the events of the 1947 Partition of India and Pakistan. It was the cry that a mob of Muslim rioters shouted as it descended upon Hindu settlements. It was a war cry.

Within a few minutes, battle cries flew at us from every direction. They rushed towards us like poison darts.

“Hum kya chaaaahte: Azadiiii!

Eiy zalimon, eiy kafiron, Kashmir humara chhod do”

(What do we want—Freedom!

O tyrants, O infidels, leave our Kashmir.)

Then the slogans ceased for a while. From another mosque came the sound of recorded songs eulogising the Mujahideen resistance to the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. The whole audio cassette played through, and then the slogans returned. We were still wondering what would happen next when a slogan we heard left us in no doubt. I remember Ma began to tremble like a leaf when we heard it.

“Assi gacchi panu’nuy Pakistan, batav rostuy, batenein saan.”

The crowd wanted to turn Kashmir into Pakistan, without the Pandit men, but with their women.

They’ll come and finish us. It is just a matter of minutes now, we think.

Ma rushed to the kitchen and returned with a long knife. It was her father’s. “If they come, I will kill her,” she looked at my sister. “And then I will kill myself. And you see what you two need to do.”

Father looked at her in disbelief. But he didn’t utter a word.

We are very scared. We do not know what to do. Where would we run away to? Would Ma have to kill herself? What about my sister?

My life flashed in front of me, like a silent film. I remembered my childhood with my sister. How I played with her and how she always liked to play ‘teacher-teacher’, making me learn the spellings of ‘difficult’ words.

B-E-A-U-T-I-F-U-L

T-O-R-T-O-I-S-E

F-E-B-R-U-A-R-Y

C-H-R-I-S-T-M-A-S

P-O-R-C-U-P-I-N-E

I remembered the red ribbon she wore; I remembered how she waited behind the closed gates of her school to catch a glimpse of Father’s shoes from beneath; I remembered how she threw a duster at one of her friends who tried to bully me; I remembered how I left her alone in the middle of a game of hopscotch because I saw Ravi’s mother entering the house with a parrot in a cage. Would Mother stab her? And herself? What would we do?

“The BSF will do something,” Uncle said. But nobody did anything. The slogan-mongering continued all night. We could see searchlights from somewhere making an arc over and over again. Was the BSF keeping a watch? Why were they not stopping this madness?

The slogans did not stop till the early hours of the morning. We remained awake the whole night. As the first rays of the sun broke, I dozed off for a while and when I woke up everyone was still there. Ma was still holding on to the knife.

The crowd took a break in the morning. I don’t think we had ever been as happy as we were when dawn broke that day. It gave us an elemental sense of hope, of security.

It was later that we realised that it was not only in our locality that this had happened. These incidents had occurred all over the Kashmir Valley at around the same time. It was well orchestrated. It was meant to frighten us into exile.

Shortly afterwards, we slipped away from home one morning and took refuge in my mother’s sister’s house. Her family lived near an Army cantonment, and it was safe there. Father spent the day listening to news bulletins. But state radio and television carried no news reports. It was only BBC Radio that gave the correct picture. From these news reports, it was clear that the situation in the Valley had spiralled beyond control.

After a week or so, Father grew restless and wanted to return home. So we left my sister behind, and the three of us returned late one afternoon.

The whole neighbourhood had moved out. The entire locality was deserted. The Razdans had left, so had the Bhans and Mattoos. It looked like a ghost street. Not a soul was to be seen anywhere. We slipped inside our house like robbers. We walked past the kitchen garden, frost-ridden and barren, and entered the house through a side door. Then Father made sure the main door was locked so if somebody were to check, he would think the house was vacant, like every other house in the locality.

Father instructed us not to switch on any lights and to keep the curtains drawn across the windows. He also urged us to speak in hushed tones. To feel a little more secure, Father had asked one of his staff members, Satish, to come and stay with us. Satish had married recently, and Father and I had attended his wedding in Budgam. Satish had made his family move to Jammu. His government job had been hard to come by and he was not sure if he would be able to keep it were he to move to Jammu, so he stayed behind.

We just sat there in a room upstairs and talked about the situation. Satish spoke about how Pandits were being killed all across the Valley.

Suddenly, we hear laughter outside. Then someone passes a remark and there is the sound of laughter again. Father goes to the window and after taking a deep breath lifts the corner of the curtain to look outside. I kneel on the ground near him and peep outside as well. Near the main gate below, there is a gang of boys. Some of them are smoking. I know most of them. They are boys from our neighbourhood—near and far—and I have played cricket with some of them. Their ringleader is a boy who lives nearby. “He is even trained in rocket launchers,” one of them says loudly, boasting about his cousin who is with a militant group now.

“Let’s distribute these houses,” one of them shouts. “Akram, which one do you want?” he asks.

“I would settle for this house any day,” he points to a house.

“Bastard,” shoots back another, “how you wish you could occupy this house with their daughter!”

There is a peal of laughter. They make obscene gestures with their fists and Akram pretends as if he is raping the girl and is now close to an orgasm. Since I am kneeling next to Father, from the corner of my left eye, I can see that his legs have begun to shake.

In the next few minutes, all of them have one house each. In between they discuss other girls. And then Akram asks the ringleader, “Hey Khoja, you haven’t specified your choice!”

The ringleader is wearing a pheran and there is a cricket bat in his hands. He is smoking. He savours the question for a moment. Everybody is looking at him now. The ringleader then turns and now he is facing our gate. He lifts his arm, and points his finger towards it. He lets it stay afloat in the air for a moment and then he says it.

“I will take this!”

The corner of the curtain drops from Father’s grip. He crumbles to the floor right there. He closes his eyes and is shaking. I think I hear someone from the gang shouting: “Good choice, baaya, good choice.”

Then it all blanks out. I can hear nothing more. There is a buzzing sound in my ear, as if my cochlea has burst. One of them must have then picked up a stone and thrown it at Razdan’s house.

The sound of glass breaking tears through the freezing air. Pigeons take flight. A pack of dogs begins to bark.

“Haya kyoho goy,” says one of them, “you have incurred losses upon Akram. Now he will have to replace this windowpane.”

“At least go inside and piss; like a dog you need to mark your territory.”

And then they leave. Their voices grow distant till they completely fade away. Silence prevails again except for the staccato barking of mongrels and the cooing of pigeons that are returning to the attic.

“It’s over,” Father said. “We cannot live here anymore.” Ma went to the storeroom and fetched a few candles that she always kept handy. In candlelight, she made turmeric rice. There was neither will nor appetite for an elaborate dinner. We ate silently, and quite early. I was so stressed that my stomach was in knots. Satish was feeling cold and Father told him to take one of his sweaters from our huge wooden wardrobe. I went with him. While he looked for the sweater, he nervously took a crumpled cigarette from his trouser pocket, lit it, and pulled so deep that the cigarette finished in three or four drags. After he left the room, I picked up the cigarette butt and lit it again till the filter burnt. I was nervous and thought a few puffs would calm me down.

Father told us we would have to leave early the next morning. That night we couldn’t sleep. We just lay beneath our quilts and Ma kept her torch beside her as usual. Father spoke to Satish in hushed tones. In the middle of the night, we heard a thud as if someone had jumped from the boundary wall into our compound. It turned out to be a false alarm—a pigeon had pushed a loose brick from the attic on to the ground.

Early in the morning, it had begun to snow. There was snow already on the roads and some of it had turned into slush. Father said he would first venture out and see if it was safe for us to leave. I held his hand and both of us came out onto the street. Father closed the gate very softly behind us. Suddenly, a bearded man wearing a thick jacket appeared on the other side of the street. His pockets were bulging. His eyes fell on us and Father fumbled. His grip on my hand tightened and we turned back. Father pretended as if he had forgotten something inside the house. We hurried in, with Father locking every door behind him.

After a while, we came out again. At the main gate, painted blue, Father saw a piece of paper that had been stuck onto it. It was a hit list. Written in Urdu, with ‘JKLF’ across the top, it warned Pandits to leave the Valley immediately. A list of about ten people followed—the list of people who the JKLF said would be killed.

I read some of the names. Some of them were of our neighbours. “We must tell Kaul sa’eb about it,” Father said. Together, we almost ran to his house.

“I hope nobody sees us,” Father muttered.

The previous evening, we had seen our neighbour,

Mr Kaul, at the bus stop. Father and he had got talking and Mr Kaul had said he was going to stay put.

“Pandita sa’eb, you don’t worry. The Army has come now, and it will all be over in a couple of months,” he had said.

At the Kaul residence, the first thing I noticed was that the evergreen shrubs that had not been tended for weeks now. The main gate was open and we entered. We found the main door locked.

“Maybe they are inside,” Father said. Very hesitantly, he called out Kaul sa’eb’s name. There was no response. The Kauls had left already. We hurriedly turned back. Satish and my mother were waiting. Ma had packed whatever she could. And we left immediately.

At the blue gate, Father stopped and turned back. He looked at the house. Looking back, there was a sense of finality in his gaze. There were tears in his eyes. Ma was calm. Satish stood next to me. Nobody uttered a word. Before we moved on, Father recited something that I remember well. The howling of a dog near one’s house was believed to be a bad omen. So if it happened, the occupants uttered: Yetti gach, yeti chhuy ghar divta (Leave from here, O misfortune, this house is guarded by the deity of the house).

JAMMU, 1990

They found the old man dead in his torn tent, with a pack of chilled milk pressed against his right cheek. It was our first June in exile, and the heat felt like a blow in the back of the head. His neighbour, who discovered his lifeless body in the refugee camp, recalled later that he had found his Stewart Warner radio on, playing an old Hindi film song:

Aadmi musafir hai / Aata hai, jaata hai

(Man is a traveller / He comes, he goes)

The departed was known to our family. His son and my father were friends. He was born in Kashmir Valley and had lived along the banks of the Jhelum River.

Triloki Nath was cremated quickly next to the listless waters of the canal in Jammu. Someone remarked that back home the drain next to the old man’s house was bigger than the canal. The women of the family were not permitted to wail in his memory. The landlord of the one-room dwelling where Triloki Nath’s son lived had been clear: he did not want any mourning noises inside his premises. He said it would bring him bad luck.

It was barely a room. Until a few months ago, it had been a cowshed. Now the floor had been cemented and its walls were painted with cheap blue distemper. The landlord had rented out the room on the condition that no more than four family members could stay there. More people would mean more water consumption. The old man was the fifth member of the family, and that was why he had been forced to live alone in the Muthi refugee camp, set up on the outskirts of Jammu City, on a piece of barren land infested with snakes and scorpions.

We had been forced to leave the land where our ancestors had lived for thousands of years. Most of us now sought refuge in the plains of Jammu, because of its proximity to home. I had just turned fourteen, and that June, I lived with my family in a small, damp room in a cheap hotel.

We went to the refugee camp sometimes to meet a friend or a relative. When I went there for the first time, I remember being confronted with the turgid smell of despair emanating from people waiting for their turns outside latrines, or taps. New families arrived constantly, and they waited at the periphery of the camp for tents to be allotted to them. I saw an old woman wearing her thick pheran in that intense heat, sitting on a bundle and crying. Her son sat nearby mumbling something to himself, a wet towel over his head.

One afternoon, I went to the camp to meet a friend. He hadn’t turned up at school that day, as his grandmother had fainted that morning from heat and exhaustion. They made her drink glucose water, and she was feeling better now. The two of us went to a corner and sat there on a parapet, talking about girls.

We perspired a lot, but in that corner we had a little privacy. Nobody could see us there except a cow that grazed on a patch of comatose grass, and near my feet there was an anthill where ants laboured hard, filling their larder with grains and the wings of a butterfly. Suddenly there was commotion, and my friend jumped down and said, “I think a relief van has come.” While he ran, and I ran after him, he told me that vans came nearly every day, distributing essential items to the camp residents: kerosene oil, biscuits, milk powder, rice, vegetables.

By the time we reached the entrance of the camp, a queue had already formed in front of a load carrier filled with tomatoes. I also stood at the end of it, behind my friend. Two men stood in front of the heap, and one of them gave away a few anaemic tomatoes to people in the queue. He kept saying, “Dheere dheere.” Slowly, slowly. Some people were returning with armfuls of tomatoes. My friend looked at a woman who held them to her breast and he winked at me. Meanwhile, some angry voices rose from the front. Tomatoes were running out, and many people were still waiting. They had begun to give only three tomatoes to each person. In a few minutes, it was reduced to one tomato per person. A man in the queue objected to two people from the same family queuing up. “I have ten mouths to feed,” said one. An old woman intervened. “Do we have to fight over a few tomatoes now?” she asked. After that, there was silence.

By the time our turn came, and it came in a matter of minutes, it was clear that not everyone would get tomatoes. One of the men distributing them procured a rusty knife. They began to cut the tomatoes into half and give them away. I thought I was hallucinating. Or maybe this was the effect of the hot loo wind that, inhabitants of this city maintained, could do your head in. I remembered our kitchen garden back home in Srinagar, and all the tomatoes I had wasted, plucking them before they could ripen and hitting them for sixes with my willow bat. And now in my hands, somebody had thrust half a tomato. Others in the queue accepted it as I had, and I saw them returning to their tents.

I looked at my friend. There was nothing to say.

We returned to our private spot and threw two half slices in front of a cow.

We were fourteen. I often think of that moment. Maybe if we had been grown-ups and responsible for our families, we too would have returned silently with those half tomatoes. At fourteen we knew we were refugees, but we had no idea what family meant. And I don’t think we realised then that we would never have a home again.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

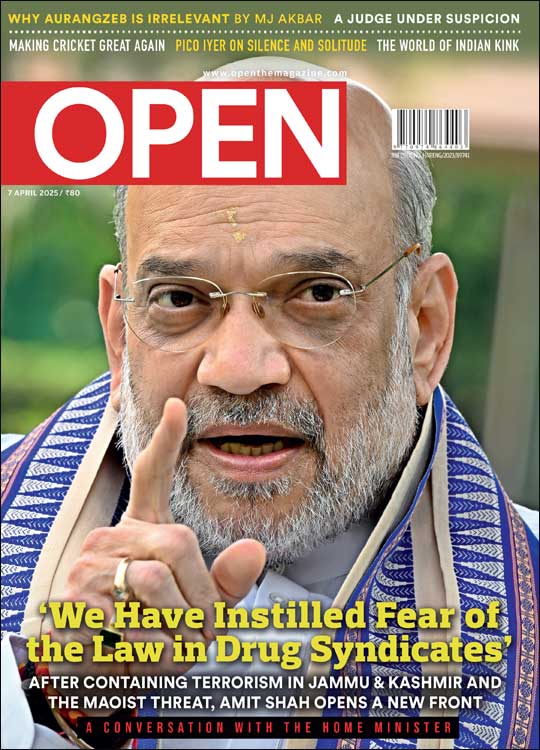

‘We Have Instilled Fear of the Law in Drug Syndicates,’ says Amit Shah

MOst Popular

4

/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Cover_Amit-Shah.jpg)

More Columns

Elon Musk attracts sharp attack over ‘swastika’ from Indians on social media Ullekh NP

Yunus and the case of a "land locked" imagination Siddharth Singh

Why CSK Fans Are Angry With ‘Thala’ Dhoni Short Post