Everything You Know about Tamil Films Is Probably Wrong

The Tamil film industry is an extraordinary place

Nandini Krishnan

Nandini Krishnan

Nandini Krishnan

|

08 Mar, 2013

Nandini Krishnan

|

08 Mar, 2013

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/tamcin-1.jpg)

The Tamil film industry is an extraordinary place

In the 1990s, the Tamil film industry saw the age of inexplicable heroes, each with a thinner moustache, redder eyes and softer paunch. Then, a young crop of male leads broke into the industry. Some of them would go on to become the biggest stars of the new generation. Among them were Ajith Kumar and Vijay, both of whom switched from romantic roles to action roles. It was a quasi-replay of the Kamal Haasan-Rajinikanth rivalry—their fans, too, would often clash with each other, till Ajith disbanded all his fan clubs in 2011.

Both were unlikely stars. The half-Sindhi Ajith, now 41, was born and raised in Andhra Pradesh. He got into modelling, and later films, to fund a career in motor racing. His debut was in Telugu, and initially, someone had to dub for him in Tamil. His Tamil still carries the tinge of an Anglicised accent. Many of his early films, mostly family dramas and love stories, were critically acclaimed, but few were box office hits. Ajith turned ‘action hero’ with AR Murugadoss’ Dheena in 2001. The nickname given to him by his fans, ‘Thala’ (literally, ‘head’) is from the film too. For Ajith, that marked the beginning of a series of critically panned but commercially successful films.

Of these, the biggest hit was Varalaru, the story of an effeminate dancer who rapes a woman to avenge the death of his mother, which was caused by a cardiac arrest that, in turn, resulted from the woman mocking his feminine bearing and dumping him at the altar. Now branded ‘Ultimate Star Ajith’, he appeared in a triple role—as the dancer and as his twin sons.

The climax of the film involves the dancer, now in a wheelchair, getting off the wheels to fight the antagonist, and the big revelation is that he feigned his crippling to atone for the rape.

Vijay made his entry as a scrawny, curly-haired youngster who spent half his films dancing with a group of extras. It made no sense for him to be either an action hero or a romantic hero. However, after a series of bewilderingly successful romantic films, Vijay switched to action. He clicked. Since the early 2000s, he’s churned out hit after mindless hit. The latest, Murugadoss’ Thuppakki, marries terror with the love story of an Army captain and a female boxer.

Having rejected her in an arranged marriage set-up, because he finds her too traditional with her long hair (which turns out to be a wig) and translucent sari (which she later discards for shorts and spaghetti top), he realises he made an error of judgment when he sees her at a college boxing tournament that merits police security; after taking a few hits on being distracted by his presence, she visualises him rejecting her, screams, “Aaaiiiiiiiii!” and knocks down her opponent. This is the trigger for a dream song called Antarctica. After asking whether she’s a penguin or a female dolphin, the lyrics move on to suggesting that radar technology must be used to track the captain’s heart and sonar to measure the depth of his love. Through the song, the boxer plays American football with a rugby ball and soccer kit, throws a javelin, and plays tennis, basketball and volleyball. Their love is cemented when she confesses that she’s smoked and still has a weakness for red wine.

Though there were protests against the film by Muslim groups, the film netted Rs 180 crore at the box office, according to the financial report released by Eros International for its quarter ending 31 December 2013. It will soon be remade in Hindi with Akshay Kumar in the lead. Vijay’s efforts have earned him the title ‘Ilaya Thalapathi’ (Young Commander) from his fans.

At some point in his career, he also acquired the habit of biting the collar of his shirt in a trademark gesture that begs lampooning.

It has been an interesting decade for Tamil cinema. Films are made on budgets that wouldn’t have been dreamt of in the industry earlier. The production cost of Raavanan was estimated at Rs 55 crore by IMDb (Internet Movie Database) and that of Thuppakki at Rs 65 crore. According to a 2012 report by Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu (Media and Entertainment in South India), Tamil films took Rs 1,030 crore in revenues in 2011-12. For big-budget films, Rs 2-2.5 crore is usually spent on publicity alone, and the visual effects budget could range from Rs 5 crore to Rs 10 crore. Deloitte attributes such spending to ‘corporates and big studios like Eros and Fox Star crowding the regional film industry’, drawn by the low-cost, high-margin factor. And in looking for avenues of revenue, their makers reach out to the North as well as international market. New heroes have emerged across genres—complete with epithets like ‘Ilaya Thalapathi’, ‘Thala’, ‘Ultimate Star’, ‘Chiyaan’ (Vikram), ‘Little Superstar’ (Silambarasan) and so on—even as the stars of the 80s and 90s kick on, battling villains and arthritis. And with a series of successful spoofs, Tamil cinema has finally learnt to laugh at itself.

In the league of Ajith and Vijay is the superhero, Surya, now 37, who starred in the Tamil originals of both Ghajini and Singham. He has worked with Murugadoss on the big grosser, 7 Aum Arivu (literally, ‘The Seventh Sense’), which co-starred Shruti Haasan. After false starts in the late 90s, his breakthrough came in Kaakha Kaakha in 2003. He also acted in Mani Ratnam’s Ayutha Ezhuthu (the Tamil version of Yuva), and is believed to be working on a sequel to Singham, but has never attempted to enter Bollywood.

Sharing space with Surya as a ‘mass hero’ who can also act is 46-year-old Vikram, who was seen most recently in both the Hindi and Tamil versions of David, after debuting in Bollywood with Mani Ratnam’s Raavan. The actor, who tried unsuccessfully to make a mark throughout the 90s, spent years dubbing for several actors whose Tamil was not fluent, including Ajith and Prabhu Deva, who is Kannadiga. He was catapulted to fame by the 1999 sleeper hit, Sethu, which tells the story of a college student (played by Vikram) who rides roughshod over everyone and eventually ends up in a mental asylum after getting into a fight that leaves him with brain damage. Vikram’s acting has been critically acclaimed in several films, but he’s made his share of entertainers, some as crazy as the notorious Kanthaswamy, whose central character is a vigilante superhero with a penchant for dressing in rooster costume.

However, the actor who has been most successful straddling both Hindi and Tamil cinema is Madhavan, now 41. Introduced by Mani Ratnam in Alaipayuthey, he went on to act in Gautham Menon’s Minnale and its Hindi remake, Rehna Hai Tere Dil Mein. Since then, and especially in the past four years, he has crossed frequently between Bombay and Madras. Madhavan may be the only actor who has debuted on Hindi television, moved to Tamil cinema, and then got into Hindi cinema.

Looking back at his early years, Madhavan is candid. “Initially, I jumped on the bandwagon of doing as many films as possible, so I ended up doing close to 30-odd films in the first five years, which was ridiculous. See, when I first joined the film industry, I wasn’t expecting to make a name for myself. When it happened, suddenly, there was this utter greed to push the luck I had earlier. Everything was going too well. Action films are always going to work. But then, I was very sure I wanted to get into the archives and survive for a couple of generations. And I was seeing that my expressions were the same, my attitude was the same, my body language didn’t change from film to film. So, that’s when I consciously stepped back and decided I couldn’t keep rushing through movie after movie. I needed to get out of my comfort zone and start doing the kind of films that I really wanted to do.”

And so, he went back to Mani Ratnam, for Ayutha Ezhuthu. Suddenly, the chic boy next door was playing a coarse, crude, wife-beating lorry driver Inba. “As far as my physical transformation was concerned, I thought it was complete. Mani didn’t say anything, but I got my hair cut really short, almost bald, I grew a moustache, and I worked out a lot, and built a body, not like an athlete, but like a street fighter. People like lorry drivers lead hard lives. They’re strong, but fairly unhealthy. They don’t have cuts and muscles, they have a body full of muscle and fat.” He feels he was only partially successful with the portrayal, though, and wishes he had focused more on the way the language was spoken. Though he is Tamil and has proven adept at picking up its slang, he grew up in Bihar, and Hindi comes more naturally to him. He says he is dying to do something like Inba’s role in Hindi now.

Meanwhile, he has also been trying to push offbeat films into the mainstream arena. One of his attempts was the 2007 film Evano Oruvan, a remake of the Marathi film Dombivli Fast by Nishikant Kamat. It tells the story of an idealistic bank employee who refuses to compromise his principles. A turning point in his career makes him an angry young man, out to set society right by employing whatever means he can, so that he is eventually branded a criminal whom the police want to get rid of through an ‘encounter’. Though the film did not do too well, Madhavan does not blame the audience for it. “I was naïve as a producer, and I didn’t release it properly. I just trusted what other people told me about releases. I think if it had got the release it should have, or if it had been released at a time like this, when we’re engaging with themes like corruption, it would have done very well.”

Since 2000, the industry has seen a spate of new directors quickly become brands. Selvaraghavan, brother of actor Dhanush (of Kolaveri fame), first came into the limelight for his Kaadhal Kondein, the story of a psychopath (Dhanush) obsessed with a woman. The climax of the film is literally a cliffhanger, where the woman has to choose between saving her boyfriend and her stalker from falling into a chasm. Selvaraghavan’s next film, 7G Rainbow Colony, the supposedly angst-ridden story of a man who letches at and eve teases a woman till she falls in love with him (because that’s how women’s brains work, according to old Tamil male wisdom), became an even bigger hit. Most of Selvaraghavan’s subsequent films have been successful at the box office. The hero is typically a flawed character who is loved by the heroine despite his flaws, which include kicking her when she’s pregnant. His last release Mayakkam Enna, which starred Dhanush as a frustrated wildlife photographer, had a long run at the box office. In the film, his big break comes when the Tamil magazine Kumudam, which is usually packed with film gossip, carries a cover photograph shot by him of an African elephant. It was probably the first time anyone had seen something apart from a plump woman flashing her navel on the magazine’s cover.

Another director who became extremely popular at that time is Gautham Vasudev Menon. Nearly all his films have been remade in Hindi. His debut, Minnale, was made into Rehna Hai Tere Dil Mein, his Kaakha Kaakha became Force, and his Vinnaithaandi Varuvaaya was remade as Ekk Deewana Tha. He has often cited Mani Ratnam as a major influence on his filmmaking, and while his action-thrillers and semi-autobiographical romances have not been nearly as complex as the films of his idol, most have done very well at the box office.

Actor-director Cheran, also a maker of semi-autobiographical films, is a three-time National Award winner: for Vetri Kodi Kattu (2000), Autograph (2004) and Thavamai Thavamirundhu (2005). The first is an upbeat and somewhat patriotic film, which traces the success stories of two impoverished men after they are duped by a middleman who promises them passage to Dubai. The second follows a man and the women in his life, all of whom he wants to invite to his wedding. This nostalgia-tinged growing-up story received standing ovations at some film festivals. Thavamai Thavamirundhu explores the relationship between a father and his two sons. Though Cheran is immensely popular in Tamil Nadu, he has kept to the Tamil and Telugu film industries. Among directors, the two most unlikely migrants from Tamil to Hindi were possibly Prabhu Deva and AR Murugadoss.

Prabhu Deva, who started his career as a choreographer, was first seen as one of the dancers in the song Raja Rajathi Rajan from Mani Ratnam’s Agni Natchathiram (1988). He had slightly more screen time in the film Gentleman (1993). The following year, he played the lead in Kaadhalan, dubbed in Hindi as Hum Se Hai Muqabla. He entered Bollywood through dance too, appearing in the song Kay Sera Sera with Madhuri Dixit in Pukar (2000). But since then, he has established himself as a director. In the Telugu and Tamil industries, he has made some of the biggest hits of the last decade. In Bollywood, he has directed Wanted, starring Salman Khan, and Rowdy Rathore, starring Akshay Kumar. His latest film, ABCD, which had a simultaneous release in Hindi and Tamil, has done well so far too.

AR Murugadoss’ Ramana, which stars actor-politician Vijayakanth, stunned audiences by killing the hero. Vijayakanth rarely dies—in fact, in the film Narasimha, when he is given the third-degree with electrodes, he calmly tells his interrogators, “Only an ordinary man gets a shock when he touches an electric current. But I’m Narasimha. If current touches me, the current gets a shock.” A transformer duly bursts when they press the electrodes to his brain. However, in Ramana, he is successfully hanged.

Murugadoss made Ghajini in Hindi without knowing a word of the language. The Tamil version of the film had raised many eyebrows for its close link to Memento. But both Murugadoss and Aamir Khan told the media at the time that the director had heard about the concept of Memento, written the script, seen the film and decided it was nothing like Ghajini, and had then gone on to shoot it. If you are befuddled by what they were saying, it means they did not plagiarise. When asked at a press conference about making a film in a language he did not know, Murugadoss said Aamir Khan had taken over the dialogue through a two-step translation process, from Tamil to English, and then English to Hindi. Murugadoss said, “I don’t know Hindi at all. From knowing the Tamil words, I had to find my way through the Hindi dialogues. Every time I was stuck on a word or line, I’d call up Aamir.”

However, attempts to move between the two industries had begun far earlier. Most had been unsuccessful. Kamal Haasan couldn’t make the crossover himself with Saagar and Ek Duuje ke Liye. Neither could the highly acclaimed Tamil director K Balachander. Remakes of Tamil films like Virasat (from Thevar Magan), with Anil Kapoor’s misguided casting, were disappointments.

But Nayagan and Roja were among many of Mani Ratnam’s films that did well as dubbed versions. Often, they lost their flavour in translation, especially in scenes where language becomes important. For instance, the poignancy in Roja draws from a village girl’s inability to communicate with anyone in the North, because she speaks neither English nor Hindi. The bonds she develops with the characters played by Nasser and Janakaraj hinge on their having a common language.

But, at the turn of the century, something interesting happened. Mani Ratnam made a Hindi film (Dil Se, starring Shah Rukh Khan and Manisha Koirala), which had only a dubbed release in Tamil. In 2000, Kamal Haasan made Hey Ram, which has dialogue in Tamil, Hindi, Bengali, English and Marathi, and then remade it in Hindi. He followed this with Aalavandhan/ Abhay in 2001.

Mani Ratnam too began to not just dub, but remake his films in Bollywood. In the case of Yuva/Ayutha Ezhuthu and Raavan/Raavanan, he used different casts for Hindi and Tamil versions.

It was through Kamal Haasan’s and Mani Ratnam’s films that Bollywood actors such as Shah Rukh Khan, Manisha Koirala, Raveena Tandon, Preity Zinta, Aishwarya Rai, Abhishek Bachchan and Rani Mukherji filtered into Southern cinema. Raveena Tandon would go on to make several films in the South, as would Aishwarya Rai. Kajol had already acted in Rajiv Menon’s Tamil film Minsaara Kanavu in 1997, with Arvind Swamy and Prabhu Deva.

When I interviewed Mani Ratnam in 2007, ahead of the release of Guru, I asked him if his sudden focus on Bollywood was an attempt to spread his banner to another market, or whether it had to do with Bollywood being more receptive to the budgets he now needed. He said that, for him, it’s the subject that decides the language, which was why Dil Se and Guru were Hindi films, and a movie like Kannathil Muthamittal (which looks at the fallout of the Eelam conflict) could only be a regional film. His films set in Bombay had revolved around Tamil families in the city.

“I was hesitant for a long time to do films in Hindi, because I’m still not very familiar with the language, I’m not so fluent, and I cannot follow every word,” he admitted, “I find it very frustrating to have a script in front of me that I can’t read. I have to depend on somebody to read it out for me, and for me to correct. So, I’m still hesitant. But once I did Dil Se, I knew that it could be done, it wasn’t as difficult as I thought it would be.”

At the time, he said it was unlikely he would ever shoot a film in two languages again. “Remaking is too elaborate an effort, you know. To do the same thing twice over, to get it right two times in a row, one after the other… it just takes too much of you, and if I’m going to put in that effort, I might as well make a new film. So Yuva was only a one-off attempt. The magic to me is to do a scene when you don’t know how to do the scene, when you’re still struggling to find a way to get it across correctly. And once you think you’ve got it, to recreate whatever you’ve done before, trying to think what [we’d done] that time that was right, is not the same as discovering it for the first time.” Ironically, his next film, after Guru, was Raavan/Raavanan.

While he has often said his films are not ‘message-bearers’ but ‘reflections’, Mani Ratnam was equally clear about working in the mainstream arena, and trying to reach as many people as he can. “I’m trying to make films which will reach the popular audience. And the more serious the film is, the more I think it should go to the people. To say ‘A film is too serious’ and so ‘We’ll talk only to the elite’ doesn’t make any sense at all to me. But I feel that within this, you can make sensible films. People like Guru Dutt have done that, and this is what I strive to do with each film.”

What has irked Mani Ratnam all through, though, are charges of plagiarism. Both he and Kamal Haasan have their critics who contrive Hollywood inspirations for their films. Mani Ratnam was accused by some factions of lifting scenes from Amores Perros for Ayutha Ezhuthu/ Yuva.

“I think it is unfortunate that we think we are not capable. It is really sad. We assume we aren’t capable of thinking for ourselves, and we always look for what it could have been copied from. It is very, very sad. For example, you know Chaiyya Chaiyya, right? Luckily for me, Dancer in the Dark came out two years later. Otherwise, I’d have been told that the train song sequence is inspired from that!” The idea of an item number featuring Malaika Arora being lifted from the slow, poignant I’ve Seen it All is hilarious, but Mani Ratnam has suffered even more absurd charges in his career. “You know, we’re still under the shadow of the White man. We don’t give ourselves enough credit or enough credibility. We want to dismiss ourselves.”

Mani Ratnam moved into unexplored territory again with his fable-like Kadal, which tells the survival stories of four characters through a narrative loaded with Christian symbolism. The film has mostly bewildered critics and angered distributors (after a poor showing at the box office). And it has polarised opinion—there are those who love it, and those who hate it, a not-so-rare phenomenon for a Mani Ratnam film.

Yet, few filmmakers have polarised opinion in the last decade the way Kamal Haasan has. He has made movies with huge budgets, veering towards bankruptcy at times. Several of his dream projects, including the much-hyped Marudhanayagam, were shelved. To fund these ventures, he acted in potboilers, most of which were tremendously fun comedies, in between. His box-office hits include Thenali, Pammal K. Sambandam, Panchathanthiram, and Vasool Raja MBBS. He also collaborated with Gautham Menon on the cop thriller Vettaiyaadu Vilaiyaadu in 2006, and starred in Unnaipol Oruvan, a remake of Neeraj Pandey’s A Wednesday.

Kamal Haasan’s big films during this time included Hey Ram, Aalavandhan/Abhay and Virumandi, followed some years later, of course, by Vishwaroopam. But, though he remade several of these movies, rather than dub, they were not as successful in Hindi as in Tamil. Some even did badly in Tamil. The films that had critics in raptures, most notably Hey Ram, had disappointing collections. He repaid distributors for Aalavandhan/Abhay. Most of these films were dogged by controversy. However, this was also the period that saw some of his biggest commercial successes, including Dasavatharam, which became the highest crossing Tamil film ever, at the time, with collections of over Rs 200 crore.

Vishwaroopam has given Kamal Haasan the most trouble, with its release stalled twice. First, theatre owners were unhappy about the film being available on the Direct-to-Home (DTH) platform a day before the theatrical release.

He agreed to postpone the DTH release. Days before the film was to hit theatres, a Muslim outfit in Tamil Nadu got the film banned for two weeks. There was an appeal, and the judge ruled against the ban a few days later. But the Tamil Nadu government intervened to have the ban extended.

As the media speculated over political vendetta, Kamal Haasan said in an interview to Mid-Day: “[The Tamil Nadu government] won’t rest easy until they finish off my film and destroy me financially.” He also said, “I am going to take the print of the Tamil version of Vishwaroop and burn it in front of the relevant government office. They are aborting my baby. I might as well give it a proper cremation.”

Finally, the film released on 7 February, with some scenes muted and others edited out. By this time, fans of Kamal Haasan had already crossed state borders and flocked to theatres in Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh to watch it. These states, too, had stopped screenings a few times, but did eventually show it without cuts.

Rahul Bose, who plays the antagonist in the film, says he was surprised by the fuss in Tamil Nadu. “According to all my friends in Madras, there was nothing offensive. I don’t understand Tamil Nadu politics, I don’t understand Tamil Nadu’s religious sensibilities, so I don’t know. But what I do know is that if a film has been passed, been given its CBFC rating, it should be the responsibility of the state to support the film, no matter what. It doesn’t happen—it doesn’t happen in Tamil Nadu, it doesn’t happen in Gujarat, it doesn’t happen in Maharashtra. This is not a new thing.”

Addressing a press conference after the row was settled, Kamal Haasan said such demands for film bans were becoming a trend that needed to be challenged by people at large. Incidentally, the same week, Hindu outfits protested against a film titled Aadhi Bhagavan, and Christian groups against Mani Ratnam’s Kadal.

Though Mani Ratnam wasn’t available for comment on this particular controversy, he spoke against censorship in his 2007 interview, saying he believed it was something the British had left behind. “It’s an unfortunate thing that we’re still carrying around, that we haven’t modified, that we haven’t upgraded, that we haven’t given enough thought and exercise to. I think it will be reviewed sooner or later. I think ideally filmmakers should be trusted with self-censorship… It is just another medium—it can do what a newspaper article can do, what a radio broadcast can do, what television can do; what a musician can do, what a painter can do, what an artist can do. The rest of them don’t have censors, only cinema does.”

Meanwhile, the big daddy of Tamil cinema, Rajinikanth, suddenly came alive to the North, which has been trying desperately to make sense of him as a ‘phenomenon’. His attempts to break into Bollywood in the 80s and 90s, with films like Asli Naqli, Hum and Aatank Hi Aatank had been unsuccessful. What got everyone’s attention was the success of Sivaji (for which he was rumoured to have been paid Rs 20 crore) and the even bigger success of Enthiran/ Robot (for which he was rumoured to have been paid Rs 45 crore). Chandramukhi, his 2005 comeback from a two-year hiatus following the flop of Baba, had been remade as Bhool Bhulaiyaa in Hindi, starring Akshay Kumar. That film was more faithful to the Malayalam original Manichitrathazhu than the customised-for-Rajini Chandramukhi. But now, all of India understood that no one else could be Rajinikanth. There was just him— with his rags-to-riches story and his unfathomable stardom.

For the first time in Tamil cinema, spoofs began to enter the market. Tamil films had always had ‘comedy tracks’, which could range from slapstick to social satire. But it was understood that some things were sacrosanct. You could not make fun of Rajinikanth, for instance. Or Mani Ratnam. Or Vijay and Ajith.

The first all-out spoof was the 2010 release Thamizh Padam. It spared nobody. The film opens in a dimly-lit hospital, straight out of Mani Ratnam’s Thalapathi. The most mundane lines are spoken in one-word utterances. The film also features a satirical version of Karuthamma, a National Award-winning film on female infanticide. This is followed by an elaborate gag in which a loud female gangster is all set to rape a well-groomed, petrified male virgin. From the Rube Goldbergian device used to kill one of the villains in Apoorva Sagodharargal/Appu Raja, to Vijay’s compulsive shirt-biting, to AR Rahman’s acceptance speech at the Academy Awards, to the Hutch dog and Vodafone’s ZooZoos, Thamizh Padam left no survivors. The films spoofed by it include Nayagan, Vettaiyaadu Vilaiyaadu, Kaadhalan, Virumandi, Anniyan, Ghajini, Kanthaswamy, Mouna Ragam, Baasha and Sivaji. A song in the film, Oh-maha-zeeya, was made up of nonsense words used in Tamil movie lyrics. The film ruffled many feathers, but had a long run at the box office.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

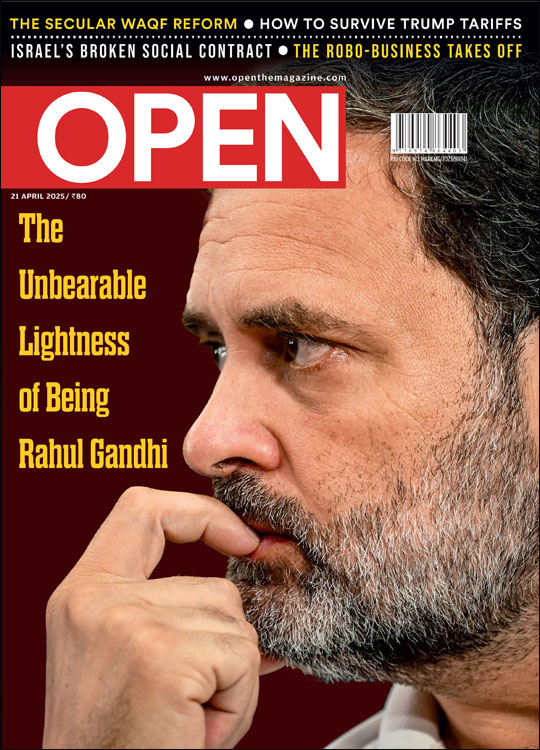

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Rahul Gandhi

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Cover-Congress.jpg)

More Columns

AI powered deep fakes pose major cyber threat Rajeev Deshpande

Mario Vargas Llosa, the colossus of the Latin American novel Ullekh NP

Speculative History Shaan Kashyap