Triumph and the Tamil Brahmin

It has never been an easy equation between the two. But the splendid World Cup victory of Dhoni's men could well change that

The last drinks have been downed. Indian men around the world, naked from the waist up, with a cigarette in one hand and a beer in the other, have got themselves banned from bars; a morning has passed and the adrenaline rush is receding. This much remains: the Indian cricket team's victory in the 2011 World Cup will have tremendous bearing on the country's collective self-esteem. This linguistically disparate nation, forged in the context of colonialism, two wars and a shrinking world, has had trouble reconciling its enormous gifts with a history of under-achievement. The multi-ethnic Indian cricket team's fortunes have often fluctuated in parallel with the destiny of this country, and captain MS Dhoni's poise at the moment of triumph will validate our sense of self just as in 1983, when Kapil Dev's ragged bunch of cricketers unexpectedly helped articulate it.

This latest win, this refusal to bow to the fear of losing, resonates strongly with me as an Indian. But as a Tamil Brahmin—which, if you didn't know, comes with the excess baggage of negativity, cynicism and plain old sarcasm—I am baffled. Yesterday, as I stood contemplating the crowd's raucous celebrations out on the patio of a downtown Austin watering hole, I felt, dare I say, ecstatic. I had no put-downs. The possibility of defeat and heartbreak now defused, I even broke into a cheer or two.

That said, I'm not your average Tamil Brahmin. I didn't grow up in Tamil Nadu. I stand over six feet tall and with my features could pass off as a North Indian, although my Bambaiya-inflected Hindi would give me away. Further complicating matters, like most heretics, I have invested too much energy in trying to prove to my parents that the way they raised me was all wrong. The only son of a scientist growing up in a Bombay suburb, I was not permitted to ride my cycle outside our cul-de-sac, even as my mother, a high school teacher, attempted to undercut my father's authority by allowing me to cycle off on exploratory jaunts when I was not playing cricket (don't get me started on the politics).

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

My father—no MS Dhoni at the best of times—would express his displeasure every time he caught me excitedly attempting to chase a cricket ball rolling out of bounds onto the main road. He was quite scary to behold. Didn't I know there was so much to look out for: rash drivers, blind turns, rash drivers making blind turns? Why tempt fate?

There is much to say in praise of Tamil Brahmins, bless our souls, but why on earth do we typically react to the fear of loss by attempting to exert as much control as possible? Why did we love employing 'I told you so' as a defence mechanism after Azharuddin's men lost yet another game in the 1990s when, make no mistake, we were bleeding just as much as you were? Why am I so unadventurous in comparison with the stereotypical Punjabi—so what if Yuvraj Singh's family is of warrior class descent—or even a Maharashtrian like Sachin Tendulkar?

Sure, there are exceptions. You don't need to assure me that there are enough courageous Tamil Brahmins who have joined the Armed Forces. And to dispute my flattering, simplistic characterisation of North Indians, an exceedingly aggravating Lucknowi acquaintance superstitiously made bets against India in the last two matches, and just to be doubly sure, announced every ten minutes on Facebook during the semi-final against Pakistan that India would somehow contrive to lose from a decent position—as if getting his friends to loathe him were somehow central to India's chances of warding off defeat. But these cases don't invalidate my argument.

Without succumbing to self-loathing, I can say mine is a community of control freaks. I make that generalisation secure in the knowledge that this behaviour is as instilled as it is institutional. Quite absurdly, I was taught at home that nobody would be friends with me unless I did well in school. If the aim was to show me the consequences of academic failure, it flopped: I learned to crave the friendship of those who perceived me as inferior, to love those who did not love me back, to perpetually attach greater value to what was out of reach.

Incredibly, such emotional violence remains systemic in the community. The Tamil Brahmin idealises what he cannot have. Having coped with damage in their own lives, most parents and responsible adults arguably lack the imagination and patience needed to demonstrate love and nurture a child's emotional health. It is an academy that churns out young Tamils with low self-esteem, and—more dangerously—whose blind spots deny them the capacity to deconstruct their false sense of ego and heal all the damage.

We have no sense of knowing how to express our feelings; just as damagingly, we aren't consciously trained to build a verbally sophisticated argument. Emphasis is laid solely on 'step-by-step thinking', which is most applicable to subjects like mathematics and science, areas that were viewed as the only acceptable options for any intelligent Tamil boy at least until when my generation was growing up. Just in case we actually live up to the stereotype and are devils at calculus, we are routinely taught to underplay our achievements. And while we are at it, we learn to coldly mock Punjabis for their grossly cartoonish attention-seeking behaviour.

As a general rule, we Tamil Brahmins are nerdy, non-confrontational, and, when pushed to the wall, exceptionally passive-aggressive. None of this should be confused with an internalised humility: we want praise alright, but we want others to blow our trumpets. When we find people disinclined to do that, we mutter under our breaths that the world doesn't value our talents, and then go back to repeating the same mistakes.

After I arrived in America to get a PhD, for the first couple of years, I was constantly thrown off by the tendency of my American colleagues (of various ethnic and racial origins, and also socially ambitious Indian acquaintances who spoke a variety of languages) to make a big show of their enthusiasm. This they did by talking up their research interests as if they breathed, ingested and excreted academia. I, on the other hand, made no attempt to establish any rapport with professors or impress them in such ways, believing that my work ought to speak for itself.

Big mistake. My advisors thought I had lost interest in what I was doing. I quickly rectified this by assuring my professors breathlessly that I certainly enjoyed what I was doing, which, unlike the typically Tamil Brahmin, excruciatingly self-parodic aspect of my performance, was never a lie in the first place.

In spite of my proclivity for smug introspection and narcissistic existence (masked, if you observe, by a Spartan outlook), the Tamil Brahmin ought not to be analysed in isolation, along a single axis of identity. Therefore, applying a wider cultural lens, I find that I belong to an India that is at once familiar and foreign, an India whose identity is constantly shape-shifting between eager supplicant and economic heavyweight, an India that is at times unrecognisable to me from just five years ago.

I was in India this January. During a quick run to a fancy suburban Mumbai mall, I paid Rs 100 for a dosa and coffee, and the dollar price for clothes that weren't a patch on the stuff Indian companies export to the US. India's local culture still operates on the laissez faire principle of let-others-take-care-of-everything. Yet, things are changing: the threshold of tolerance for governmental corruption has been breached, the middle class has gained some weight, the needs and desires of this diverse population are growing.

We are learning to ask pertinent questions. The political ideology of cultural oneness has traditionally worked much better in India than in the US. In part, this is because differences in skin colour and facial features, which are less perceivable among Indian social groups, are a more obvious divisive factor in the case of America; and also in part because state ideology is rarely questioned in Indian classrooms. In the 'land of the free', radical anti-social tendencies are held as unacceptable; in India, the expression of individuality itself is derided as rebellious and viewed as an affront to the social order, even oneness. Cue revolution to overthrow the status quo, but instead Gramsci's conception of 'the organic intellectual' is subverted by the likes of Karunanidhi and Bal Thackeray, and the Indian public sphere remains captive to haphazard outbursts of emotion.

Now, emotional outbursts are not necessarily a bad thing—the Enlightenment's snobbish stress on reason over feeling has skewed both Western liberal and, by osmosis, Tamil Brahmin perceptions of sophistication—but so long as the poorly-educated continue to be manipulated by parochialists and intellectually dishonest leaders, the minority middle class (always obsessed with social ascent) will view intellect as the prime tool with which to distinguish itself. Any empathy vis-à-vis others will be replaced by an instinct for self-preservation. Stereotypes of apathy and political disengagement will be reinforced, social progress impeded. Why must it take the degree of cruelty exercised by a Mubarak or Gaddafi to provoke political change?

Elsewhere in the world, having grown up without the sense of entitlement that is so embedded in the Western heteronormative experience, the Tamil diaspora and Indian population at large are capable of adapting without complaint or controversy to any social circumstance. With a mix of pride and ruefulness, I say then, we are like rats: capable of surviving but not welcome at dinner. On account of reasons ranging from racism to the alienating experience of otherness, I am of the belief that try as we might, we will never truly fit into foreign cultures through performances of Whiteness. The act of the noble savage is not the one to adopt.

As India consolidates its global presence as a thought leader and gives up the old habit of fitting into whatever space is available, we risk falling into the trap of seeking solutions for problems like wealth disparity and caste wars in problematic Western models of wisdom and modernity. I certainly didn't connect, intellectually or emotionally, with Tennyson's immortals of whom I read in my class VI English poetry volume, and of whom it was said, 'Into the jaws of death/Into the mouth of hell/Rode the six hundred'. Suffice to say my experience was limited to riding safely, along the outer rim of the mouth of hell.

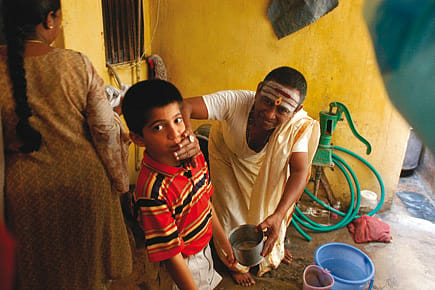

But pointing fingers is futile and ultimately misses the context. My father, a Tamil Brahmin if there ever was one, chose through no fault of his own to try and protect me at all cost from everything that could go wrong. I am grateful for everything that he has done for me, the life lessons that he taught me, even if some of these were inadvertent.

I have since learnt that the most effective way to transform my life is to perform small corrective actions that snowball into demonstrably-altered behaviour until it becomes second nature. It is imperative that subsequent generations of Tamils invent their own reality, one in which they are humble enough to learn from the experiences of others, yet confident enough—in the manner of this amazing cricket team—to tackle problems with self-belief. Perhaps some day in the near future, this Tamil Brahmin, inspired by Dhoni's sense of fearlessness, will let his child explore the world outside, get a feel for it—on a bicycle.