Woven In Time

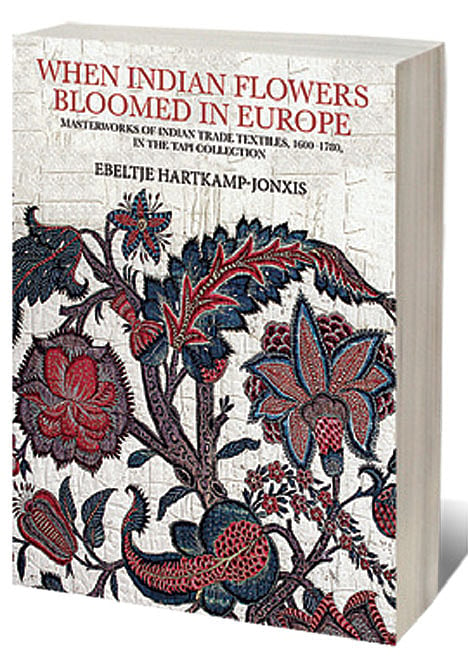

AT A TIME when any positive mention of the effects of European colonial expansion has been declared verboten, the catalogue under review re-ignites the splendour of Indian textiles along the “Spice Route”.

It foregrounds the Tree of Life in all its variegated forms as devised by the artisans working during the boom in exports of printed, painted and embroidered fabrics meant for the European market in the 17th and 18th centuries, most spectacularly from the Coromandel Coast. There are also exquisite pieces from Gujarat and the Deccan as may be expected with the Surat-based TAPI collection, named after the Tapi River, by Praful and Shilpa Shah, the curators of the collection.

They have taken a leaf, or more accurately several leaf forms, from the legendary Calico Museum of Textiles in Ahmedabad to create a moveable feast of the textile wealth of the country. Instead of confining the collection to a museum, the TAPI collection believes in showcasing links between these fragments of the past in select exhibitions and monographs.

The collection that was chosen specifically for viewing at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya in Mumbai focuses on those that were traded by the merchants of the Dutch trading company in 1602 who were hot on the slipstream of the East India Company. The European merchants catered to the demand for luxury items in food, fashion and interior decor following the opening of the sea route to the then fabled East.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

They picked up the cotton textiles from Gujarat and the Coromandel Coast as exchange for the spices from the Indonesian archipelago. As noted in the introduction, the Dutch took their textile cargoes further to West Africa, present day Ghana and the Guinea Coast, where they were highly prized and used for ceremonial occasions such as births, marriages and funerals. There is a double page devoted to the plaid, or checked cotton textiles popularly known as the Real Madras Handkerchief. The text alludes to how these came to be traded to the US and the Caribbean on the backs of ‘enslaved Africans’. Do we add that these achieved a certain post-colonial notoriety when they were knotted around the necks of American cowboys as ‘bandanas’ and even later as a product that gained traction in the 1970s as ‘Bleeding Madras’?

With superb scholarly inputs by Ebeltje Hartkamp-Jonis, the great triumph of the catalogue is to reproduce with extensive references to their provenance and subsequent display in museums around the world, the best samples of the painted and embroidered fabrics of that early era of expansion. It’s difficult not to describe them as ‘hybrid’ as Hartkamp-Jonis murmurs at one point with influences from Central Asia, China and Japan to cater to the European demand for the exotic. Yet they are also grounded in the Indian craftsman’s innate instinct for the use of local colours and abundant variety of animal and plant life forms. In a series of exhibitions entitled ‘Visvakarma-Master Weavers’, the years between 1980 and 1990 inaugurated a decade of extraordinary fellowship between bureaucrats, artists at several Weavers Service Centres, designers and visionary mentors by bringing together craftspersons and a new clientele.

The Tree of Life is a motif that finds a reference in Norse legends as Yggdrasil. Or as Kalpa Vriksha or wish-fulfilling tree in Indian mythology, or the Chinese Peach tree that produces a fruit every three thousand years giving immortality to the individual who chances upon it. Science also tells us that every organism has probably descended from one common ancestor, or source. It’s given us a word, phylogenetic, to explain how these divergences occur. The book is a celebration of this diversity that has survived in all its manifold expressions of Indian craftsmanship through the centuries.