When Worlds Meet

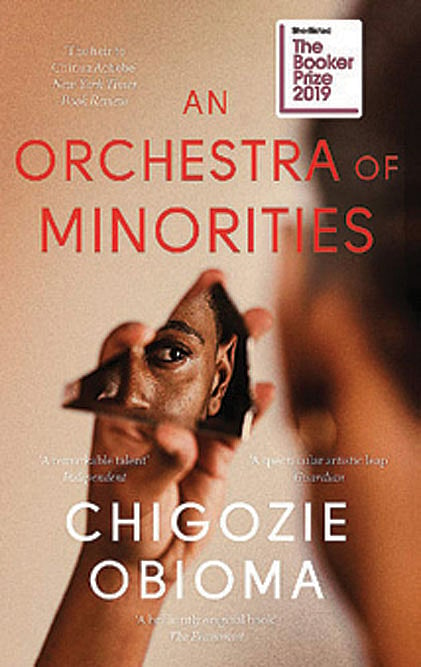

WHAT DOES SOMEONE’S life look like from both the inside and the outside, roiling contradictions, fleeting emotions and all? Just ask his chi. In Chigozie Obioma’s An Orchestra of Minorities, a chronicle of a tragedy is retold through the protagonist’s chi, or guardian spirit that inhabits every person according to the Igbo belief system.

When Obioma’s novel opens, a chi is keenly petitioning a group of other-worldly beings making a case for his host Chinonso, a young poultry farmer from Umuahia in south eastern Nigeria. Chinonso appears to have committed some dastardly act whose details are not fully clear, but his chi is narrating events and extenuating circumstances he hopes will excuse him.

Stretched over 500 pages and infused throughout with incantations, repetitions and circular segues, the narrative heaves under the weight of what it sets out to do.

This is Obioma’s second novel, and also his second to be shortlisted for The Booker Prize. Nigerian fiction is having a spirited literary moment, and Obioma has already been hailed as the heir to Chinua Achebe.

While it comes wrapped in the pageantry of Igbo folklore and cosmology, in essence Orchestra is a straightforward story: a man is separated from the woman he loves, and a series of unfortunate events befall him in his quest to regain her. Chinonso, a young chicken farmer is returning home one night when he sees a woman keeling over a bridge, looking like she wants to end her life. After talking her out of suicide, Chinonso returns to his routine, until a subsequent chance meeting with the woman, Ndali, metastasises into a full-blown romance. It’s an old story, with an old problem: Ndali is wealthy and educated, while Chinonso sells poultry for a living, putting the love-struck couple directly in the crosshairs of her family’s displeasure. The indignities sting. The impetus to surmount his station bubbles.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

What Chinonso ends up doing next will place him on an irreversible and eventually cataclysmic path to misfortune: he sells everything and enrols at a university abroad with the help of an old acquaintance. The hope is, he will return educated and polished, finally deserving of Ndali. The reality is, he will return, but changed and woebegone.

When he leaves for Cyprus, the Homeric journeying sequence kicks into play; there are even explicit references to the Odyssey, laying out clearly the novel’s epic template.

Throughout the first half, the imprint of the White Man’s world on Nigeria is noted everywhere, often elegiacally; whether in religion or language. But that encounter between worlds is taken up by several volumes when the Nigerian sets foot in white country, facing the many textures of racism; from simple taunts to more egregious assaults.

The innovative device of having the chi narrate the story allows a bird’s eye omniscience across space, time and the deeper workings of Chinonso’s mind. While a spirit can plant suggestive thoughts or anticipate outcomes, it can never determine its host’s decisions, leaving it as much a witness to the unfolding tragedy as us. There is an animating frisson between what we see, and what could have been, what we know now, and what our hero did not know then. How much of the tragedy was preventable, how much was predestined?

Obioma is fully in command of language, writing pretty and mellifluous sentences, and the shape of the tragedy has its own raw power. But eventually, nothing can rescue Orchestra from its own verbosity and ambition; the novel plods, extended for too long at 512 pages. Key dramatic points lose their potency in the digressions of the chi, whose narration often undermines rather than enables his host’s cause. This also serves to distance us from the protagonists, and ultimately the tragic hero, operating on a cocktail of rage and possessiveness, becomes impossible to root for.