Walking the Shoreline

WHEN I SPEAK TO the naturalist Yuvan Aves, more than a month has passed since floods, once again, wreaked havoc over large swathes of Tamil Nadu. The office of the Palluyir Trust for Nature Education and Research, founded by him, was inundated with several feet of water, destroying lakhs worth of equipment in the process. With the help of donations, Aves has since moved his team three streets away into a new space on the first floor—an ark to hedge against future floods.

Situated on the coast in the path of the northeastern monsoon, the densely populated and over-built city of Chennai is particularly vulnerable in instances of extreme weather. The latest floods caused by heavy rains were reported to have affected over a crore people. Aves’ activism has long been anchored in efforts to spread awareness about and oppose industrial projects and resulting pollution in fragile landscapes around the city— most recently, gas leaks in the Ennore area that have taken place with impunity for the past forty years. As an educator, he organises nature-based walks and publishes specialised guides aimed at local schoolchildren. This equips them with language and knowledge of the local ecosystems in which they are stakeholders. Aves is fostering the kind of young and engaged citizenry that the urban spaces of India desperately need.

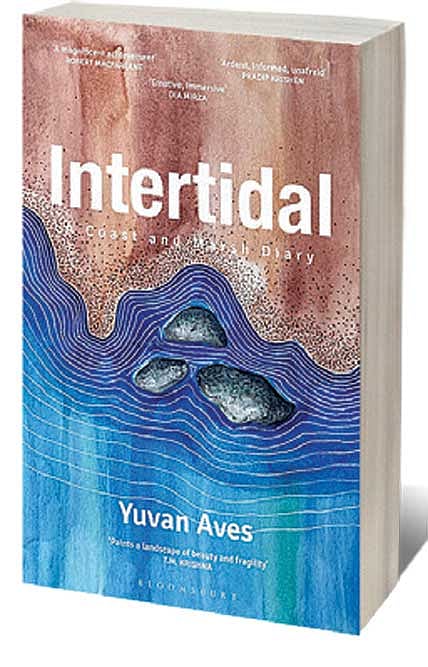

For years, I have followed Aves’ writing on the wilds of Chennai. Shared on his social media, his photographs and thoughts on local biodiversity, with a particular focus on the city’s shoreline, are a blend of information, political agitation, and philosophy. When speaking of carpenter bees, he brings to light their unusual choice to nest in intergenerational groups. For him, the openings in a termitary are portals, environmental activism is an extension of one’s spiritual self, and lichen are inherently radical organisms. Intertidal: A Coast and Marsh Diary (Bloomsbury; 286 pages; ₹699), his latest book, is part naturalist’s diary, part philosophical thesis on what constitutes a meaningful life.

It's the Pits!

13 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 58

The state of Indian cities

An intertidal zone—an area covered by water during high tide and exposed during low tide—is, by definition, an area of flux. This site of anxiety and discovery, impatience and imagination, is a place for observation and contemplation for Aves (and many others). Typically, such a zone supports a wealth of plant and animal life such as seaweed, barnacles, crabs, and anemones to name a few. Having spent time on the beach since he was a child, he gleans various lessons from the relationships between these species, the soundscape of a rich ecosystem, and stories the fishing community shares with him of an unpredictable sea and changing times. These intertidal habitats are rapidly shrinking due to intensive land reclamation.

The short, thoughtful essays that make up this text travel through various neighbourhoods and communities in Chennai, cataloguing both dwindling natural beauty and encroaching development, trash and environmental contamination. Aves draws heavily from conversations he’s had with local fishermen and others working on the city’s conservation efforts. His deep respect for various kinds of knowledge—emotional, sociological, and scientific—allows Intertidal to be far more than a series of beautiful observations, although there is no dearth of that in his writing. Similarly, the writings and theories of poets, philosophers and psychologists are used to interrogate and complicate our relationship with nature in a capitalist world. Consequently, the book leaves little room for the compartmentalisation that has become a key survival trait of our times. Though they are very different books, Intertidal often calls to mind Jenny Odell’s How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy (2019).

Aves is candid about the traumatic circumstances that had him turning to the natural world. He sees his relationship with the land as a result of reframing and redirecting the abuse he suffered. There are multiple site and weather-specific meditations in the text for a reader to attempt. “Listen keenly for a minute to the rain sound all around you…As you listen, imagine the rain in the clouds falling on the soil, on the hills, filling rivers, streams, ponds, lakes, and streams,” he writes as part of a rain-themed exercise. These simple meditations feel like ways to both pay attention to the world and to let go of it. Diverting attention towards our five senses is a powerful tool in self-regulation, and Aves recognises that one of the most effective ways to do that is by sitting in communion with the natural world.

He does not shy away from cataloguing ecological grief either. In one essay, he is “gripped with heartache at the absence of drawn-out groans and lamb-like bleating. Frog call during monsoon weather has become for me a spiritual necessity.” Who among us cannot think of a tree we no longer see, a fruit that no longer winds its way onto our tables, a flock of birds that ceased visiting the neighbourhood, or a sky whose blues are a memory? Is that feeling of loss not nearly universal? Aves’ words were a reminder of minor joys I had not even noticed I had lost.

Time and time again, he challenges the idea of the self as isolated from the whole, drawing examples and reasoning from both the natural world and theorists. He stresses the need for understanding generational suffering in displaced communities. He wishes to remind people that, “The mind is transgenerational rather than set in the skull of different individuals.” His friend and fellow activist Nityanand Jayaraman recently told him about Senjuramma—an ocean deity worshipped by the Irular people of North Chennai (a section of the city severely impacted by industry). One of the offerings the Irulars leave on the beach for the deity is the flower of the pandanus bush. It is believed these bushes will not be found by those looking for them—they can only be stumbled upon by chance. However, the shoreline in North Chennai is disappearing due to erosion. “When the embodiments of god in the local living landscape vanish, the roots to sacrality vanish,” he laments.

The places in Chennai he writes about have been experiencing industrial abuse since colonial times. He distinguishes the impact that has on a society versus an individualist mental health scenario. “I’m not watering that down,” he clarifies, “but it’s different. In these places, there’s a communal grief and resistance in the land, in the community, in the birds. There’s a weight and historicity to it.” In 2022 alone, 2.5 million Indians were displaced due to natural disasters — 96 per cent due to flooding. The psychological impact of such misfortune is sorely underreported and under-researched.

Intertidal is the culmination of two years of walking in his city, carefully observing, listening and asking questions. He strongly believes that a pedestrian society results in an engaged citizenry—pointing out that transformational actions like marching and sit-ins require direct engagement with public spaces. Walking, even when uncomfortable, “allows people to imagine forms of urban planning that aren’t visible till you experience public spaces and perforates what has been presented as possible to you. Until that happens, the old systems will prevail.”

As a teacher at Pathashaala, he tells me he often taught his students under an Indian Beech tree, showing them the lifecycle of creatures such as the Indian Sunbeam and the Death’s Head Hawkmoth. When the school administration decided to build a seating area where the tree stood, Aves and a few other teachers campaigned to save the tree. He began to take his students to the tree with increased frequency, having them create timeline journals and relationships webs, and track lifecycles. But the tree continued to grow, eventually cracking the cement in the new seating area. The administration was furious. When Aves arrived at the scene, having prepared his arguments for saving the tree on his way over, he found his students already congregated there, protecting the tree they had become so familiar with.

When I ask him how he navigates unfavourable results and frequent losses in the conservation space, he does not hesitate, “Alice Walker said, ‘Activism is my rent for living on the planet.’ That captures the ethic that I and a lot of others follow—living with agency and gratitude is a meaningful life. It’s important to approach activism whether campaigning, legal fighting, or writing with a sense of service and reciprocity. It’s not goal-driven in the way that a capitalist dream is. It’s an inner way of life.”

Intertidal also offers a commentary on language as site-specific and foundational to cultures. A rip-tide becomes a ghost arm yanking one by the ankles. The sea has periods where it is described as “lying idle”. There is a word for a charm that wards off devils responsible for bad weather. Most of the words Aves delves into are functional or descriptive—a vocabulary that encompasses the tides, habitats, and winds of the region. As a man well-versed in the moods of the sea points out to Aves, words can be life and death out on the ocean. Language is access, connection, and survival. Separating a people from their land separates them from the grounding and protective nature of specific language.

At its strongest, Yuvan’s writing reminds me of the work of Helen Macdonald and Kathleen Jamie. Where Jamie communes with nature at the edges of the world and Macdonald bonds with a specific raptor, Aves finds nature’s holy aspects within the quagmire of daily life. His language is careful and evocative, constantly moving between observation and questions. “For a wandering glider,” he writes, “home is ever the wind, weather and sky. Can that even slightly enter my comprehension?” I would recommend Intertidal and Aves’ writing to anyone who enjoyed Krupa Ge’s Rivers Remember. As partial as I am to the fragmentary style Intertidal favours, I wish the text had had a more cohesive narrative that helped tie in the anecdotes and ruminations into a story of Chennai’s water bodies as a whole.