In Conversation with TM Krishna

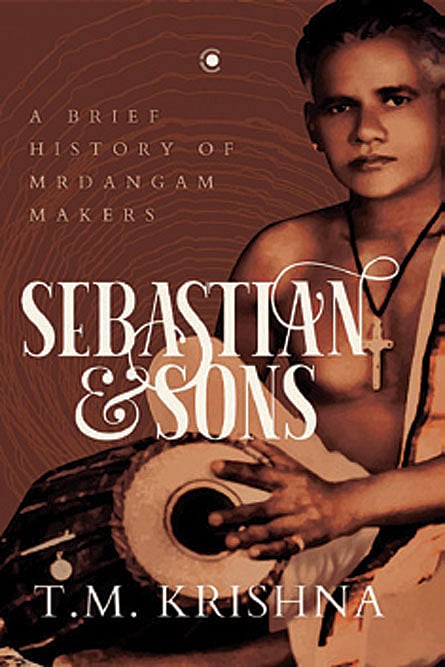

WHEN WE THINK OF rhythm, the beating heart of all music, we think of the proud visual aesthetic of a percussionist tapping in vigorous bursts on a pair of drums or a tabla player flexing his wrists and throwing back his head in artistic exuberance. We rarely think of the men who engineer and craft the instruments. TM Krishna’s new book, Sebastian and Sons: A Brief History of Mrdangam Makers, (Context; 376 pages; Rs 799) is about coaxing rhythm out of a log and animal hide, but it is about so much more. It is about the political economy of the mṛdangam, except that the relationship between the upper-caste artists and the Dalit craftsmen is not purely transactional. It is about a society that knocks down a few barriers, permitting pleasant exchanges between two very different communities, even as it erects a massive wall that cannot be scaled: the power of creation. Where does labour end and creative effort begin? How does a Brahmin mṛdangam artist in pursuit of the perfect sound distance himself from the maker who enables him to distil that sound from the hide of a cow slaughtered for the express purpose? With moving modesty, Krishna exposes the jagged iniquities of this interstitial world where Dalits and Brahmins must come together to make music.

What was it like to work on Sebastian & Sons?

This was new territory for me. I had never written anything like this in my life, where the story completely depends on what people tell you. You don’t know what you are going to get. It is not your story but theirs and your job is to try and understand it. I learnt how to do interviews, how to negotiate a question in a sensitive manner. Each voice was different. If a person said something sensitive, I was careful not to reveal their name. If I felt a quote was sensitive and the person needed to be protected, I did it—for both mṛdangam makers and artists. I grappled with the interviews—30 conversations of two hours each, 14 or 15 shorter ones—for almost eight months. I did not know how the story was going to come together. It is as much for me a discovery as anything else. Through it all, what I was sure about was that I wanted all the voices to be heard.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

What was the prime motivation for writing the book?

I was driven by my failing. When I wrote about caste in my first book, A Southern Music (2013), I spoke about communities but I had forgotten about the makers of instruments. They were never on my radar. That said something of me. That’s how it started. And I found their lives to be very interesting. Very rarely do you find people who belong to two ends of the spectrum of society having a relationship which is not just transactional, not just buying and selling. Here, there is an intimacy. The mṛdangam itself is such a mindboggling instrument and I wanted to know how they made it. A combination of all these things made me just start talking to people.

Considering the book is about the makers of mṛdangam and the unequal relationship between them and artists, it is surprising the latter agreed to speak to you.

I went to everybody and they knew the book is about mṛdangam makers and the history of making. They agreed to talk to me. I think everything has to be taken in the context of the story. The relationship is so complicated and interwoven. It’s not about good or bad, I think that’s where we are getting stuck today.

Thanks to this book, I am also looking at myself critically. I realised that someone who has been working at our home for the past 40 years, who has known me from when I was born, I call him ‘nee’. (As in Hindi, the informal second person pronoun in Tamil reflects age and rank; the deferential pronoun is ‘neenga’, ‘nee’ being the informal one, usually reserved for friends or for those younger or lower down the social ladder.) I never noticed it. Now I am making a conscious effort to call him ‘neenga’. We should think about these little things.

Did Kalakshetra’s decision to withdraw permission for your book launch at its premises in Chennai take you by surprise?

I am quite confused at the response. If you look at that excerpt, I think Mani Iyer comes across as a thinking human being. Here is a man who has a certain belief system and he also loves his mṛdangam (an instrument that must make use of cow skin). It’s an ethical struggle. Isn’t that beautiful? He engaged with it—he didn’t brush it under the carpet; let’s be clear about that. Doesn’t that make him an inspiration?

Definitely, the time period we are in today has a huge influence on the way people are reading things. Now why is that excerpt problematic? You are seeing it as an attack, while it is not. All these people are incredible artists and incredible people, and that’s never going to go away. The times are such that people are seeing red everywhere. And if it comes from a person who they believe is on a different side of the political thinking, they think the person is launching an attack. Twenty years ago, we may have disagreed, we may have argued, but this kneejerk anger and abuse was never there. We need all kinds of views. We cannot choose to only see one kind of history. There are multiple truths and we have to engage with them all.

Watching a video of you singing to a cheering audience in Delhi’s Shaheen Bagh, I was reminded that a few years ago, you would request audiences to stay quiet during your concerts and photographers to not use a flash. You have come a long way.

Engaging with worlds beyond my comfort has made me more real than ever before. There is no doubt about it. The other day I was thinking, something I thought of as noise a few years ago today sounds like music. How is it even possible? It is possible because you are listening not just to sound, you are listening to culture, your habituations of memory. If you can dissolve that, then there is a transition where it starts becoming music. I am thankful to the new people I have been introduced to, the new worlds that challenge me, put me in uncomfortable places. They have really made me feel, in a way, not burdened by who I am and made a huge impact on my music. I listen to my own music differently.

Have you dabbled in instrumental music?

I learnt the sitar for about four years. I supposedly played a concert when I was maybe 10. Now you give me a sitar and I won’t know what to do with it. I also learnt the mṛdangam briefly for about a year. But I was always fascinated by the instrument.

Isn’t the relationship between artist and maker similar to that between vocalist and instrumentalist?

In Carnatic music, the vocalist is like the lord controlling the whole damn thing. One musician even likes to call himself the captain of his ship. At every level, there is an aspiration for approval. The person who is giving the approval is in a position of power. I tried to do away with this hierarchy onstage. Now that you mention it, it is likely that looking at my relationship with instrumentalists brought me closer to looking at other hierarchies, subconsciously.

Has meeting Dalits in the Carnatic world and hearing their stories firsthand changed your understanding of caste structure?

I understand caste politics and the power plays associated with it, but intellectualising, especially coming from incredible privilege, only makes you think you understand. When people start telling you their stories, you realise who they are, and you see these little approvals they seek from the artists, and you see how complicated the dependencies between communities can be. It even makes you question notions of what love is and how affection can get muddled with power and economic need. In the case of mṛdangam makers, many craved that sharing of space, the intimacy of being able to have a chat or being able to play a prank on an upper-caste artist. This changed the nature of the relationship in their minds. Unless I had spoken to so many people, I would have never understood such nuances. As much as we know that society has so many crevasses and sliding doors, unless we start pushing the doors and going in between, we really cannot understand it.

In the book, you say that for families with social privilege, their forefathers’ achievements, however small, become a source of pride, while for a marginalised community, history is a burden. Do you mean to suggest that Dalits don’t pass on stories and memories?

Memories of culture and place are passed on but that is not necessarily true of memories of individuals. What was someone’s grandfather like—in the course of my interviews, I found these stories were much harder to come by. I feel that what happens sometimes is that because of the marginalisation, because of being in a position where you are irrelevant to the functioning of society, individuals are remembered only as a function of their utility, even within that family. My grandfather was a great mṛdangam maker. Great, but then what? For people of privilege it’s not just that. There is so much more we will pass on. I feel that many times these memories are lost.

Is your book is also about the line between manual labour and creative effort?

The problem of knowledge is for me a very important part of the book. I hope people read that carefully. The first time it struck me is when Rajagopal, a koothu artist, said to me, “Naan panradhu uzhaippu [What I do is labour].” I have never used that word for singing in my life. I would never call it ‘uzhaippu’. Why? It was like a slap on my face when he said that—now when something is seen as being more physical, it loses any intellectual gravity. As something is seen as less and less physical, it increases in intellectual value. This is a deep problem of knowledge creation.

Did the visit to the abattoir, where you take in the sights and smells and see firsthand how the mṛdangam membranes are made, encourage you to start eating meat?

A lot of people have written to me just to comment on that chapter. At the time, I was writing the book, I only ate fish. I was progressing. I have now progressed. I eat meat. The only thing I don’t eat is chicken. Don’t ask me why. It’s baggage.

Does the Dalit community need an upper caste writer to tell their stories?

The criticism from Dalits keeps me in check. I have learnt in the past three-four years where I need to take a step back from my engagement with Dalit politics. In this book, I was very conscious of my position when I wrote it, but not when I did the work, because it was such an important story. It didn’t stop me from doing research. In the case of mṛdangam makers, who is going to tell the story? The story can only be told by an insider from the music world. It’s a catch-22. Ideally it should be written by a maker or somebody close to the maker. And the person should be in the world of music.