Tipu Sultan: The Zealot

I SEEMED TO BE reciting the names of God on almonds amidst which I had mixed ‘salgram’ stones, salgram being an object of worship by the unbelievers. My motive in doing so was that like their idols who were embracing Islam, the unbelievers also would enter the fold of Islam. On concluding my recitation, I stated that all the idols of the unbelievers had embraced Islam and I ordered the stones to be picked out and replaced by almonds. My interpretation is that by the grace of God, all unbelievers would embrace Islam and the country would pass into the hands of the Sarkar-i-Khudadad.

Thus had dreamt Tipu once, which he dutifully and proudly recorded in his dream register. But this was not a one-off exception to his innate desire to suppress the faiths of non-Muslims. The leitmotif of his rule and its bloodstained legacy are testimony to this. There are multiple opinions about this complex and controversial aspect of Tipu’s legacy. We must evaluate his actions both within and outside the borders of his kingdom to arrive at a semblance of a conclusion.

In the manifesto that Tipu Sultan brought out on 3 May 1786 as an article of faith for his Sarkar-e-Khudadad, he leaves no room for ambiguity:

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

It is our constant object and sincere intention, that those worthless and stiff-necked infidels, who have turned aside their heads from obedience to the true-believers, and openly raised the standards of infidelity, should be chastised by the hands of the faithful, or made either to acknowledge the true religion or to pay tribute, particularly at this time, when owing to the imbecility of the princes of Hind, that insolent race having conceived the futile opinion, that the true believers are become weak, mean and contemptible; and not satisfied even with this, but preparing for war, have over-run and laid waste the territories of the Moslems, and extended the hand of violence and injustice on the property and honour of the faithful.

From the letters, the books in his library and his own dream register entries and writings, it is amply clear that innately Tipu had immense antipathy for non-Muslims and considered it his bounden, religious duty to inflict a holy war (jihad) against them. The mode of undertaking this holy war and what it sought to achieve too has been well documented in the literature produced in his time. It is a different matter whether he could fully manifest what he deeply desired or whether the practical feasibilities and harsh realities made him compromise with this wish.

Within the kingdom of Mysore, like Haidar, Tipu too realized that his subjects who comprised a Hindu majority still had an unstinted reverence and soft corner for the Wodeyar family that his father had displaced. If he had indulged in any overt iconoclastic attempts within Mysore, he knew that the simmering anger among his subjects could well boil over into a full-scale rebellion—something that he could ill afford while being engaged in bloody battles with his many enemies and crushing revolts in other places. But his thoughts, his writing and his dreams do portray the innate animosity for those who did not subscribe to his faith and belief systems and how crushing them, even violently, was constantly on his mind. Among other things the following lines were engraved on the handle of his sword: ‘My victorious sabre is lightning for the destruction of the unbelievers. Haidar, the Lord of the Faith, is victorious for my advantage. And, moreover, he destroyed the wicked race who were unbelievers.’

The eternal search for the legitimacy of his rule and to not be perceived as a usurper of someone else’s throne remained a constant narrative in Tipu’s short, yet stormy reign. The declaration of his independence from the Mughal emperor, and his many emissaries to the rest of the world, especially the Islamic nations, to seek for himself the sanction to rule Mysore, are testimonies to this burning desire within him. To achieve this, he made deliberate efforts to try and obliterate the memory and influences of the erstwhile Hindu Maharajas of Mysore on the populace. For this purpose, as Lewis Rice states, ‘even the fine irrigation works, centuries old, of the Hindu Rajas were to be destroyed and reconstructed in his own name.’ Possibly, Tipu sought a more phased and gradual Islamization of the Mysore kingdom that was predominantly Hindu. Right from coining an Islamic name Sarkar-e-Khudadad for the kingdom itself, to introducing Persian in the court and to renaming existing cities and towns with Persian- and Islamic-sounding names, these can be seen as steps towards this direction. A blanket conversion of a kingdom as seeped in Hindu heritage as Mysore was an impossibility, as he came to realize.

The Annual Report of the Mysore Archaeological Department of 1935 states the following:

Close to the eastern or Bangalore gate stood formerly a Hindu temple with a prakara wall and a verandah running around. It was very probably a structure of the early eighteenth century and was not of great architectural importance. It is said to have been dedicated to Hanuman or Anjaneya. Near it, in the field, Tipu is said to have played in his younger days when his father was yet a rising young officer in the Mysore army. One day a Fakir told the boy that he would some day become very prosperous and directed him to convert the temple into a mosque when he became a great man. When he became king, Tipu compelled the Hindus to remove the image from the temple, filled up the ground floor and on the top of the temple got erected the Jumma Masjid, the hall of which has numerous foil arches and a Mihrab on the west in the form of a small room. On the walls of the hall are found stone inscriptions with quotations from the Quran, etc. One of them gives the date of its construction corresponding to 1787 A.D. The main points of interest in the mosque are its two great and beautiful minars which combine majesty with grace. Their shafts are ornamented with cornices and floral bands while near the top are narrow terraces with ornamental parapets. From there a visitor gets a panoramic view of the neighbourhood. At the crown of the minars are large masonry kalashas placed upon flowers and fully ornamented. Above are small metallic kalashas of the Hindu type.

In recent times, this has become a site of intense conflict and contestations with thousands of Hindu activists demanding permission to perform their prayers to Lord Hanuman inside the Jama Masjid Mosque in Srirangapatna.

Tipu is said to have demolished the temple of Varahaswami—the boar avatar of Sri Mahavishnu, in Srirangapatna. This was perhaps due to the disdain with which the animal is held in Islam. After the fall of Tipu and the shifting of the capital to Mysore, the Wodeyars reconsecrated it as the Shweta Varahaswami temple in the palace complex.

During his visit to Coimbatore during 29–30 October 1800, Francis Buchanan records:

I visited a celebrated temple at Peruru, which is two miles from Coimbatore. It is dedicated to Iswara, and called Mail [high] Chitumbra [Chidambaram], in order to distinguish it from another Chitumbra, that is near Pondicherry... the Brahmans in the time of Haidar had very large endowments in lands; but these were entirely reassumed by Tipu, who also plundered the temple of its gold and jewels. He was obliged, however to respect it more than many others in his dominions; as when he issued a general order for the destruction of all idolatrous buildings, he excepted only this, and the temples of Seringapatam and Melukote. This order was never enforced and a few of the temples were injured, except those which were demolished by the Sultan in person who delighted in this work of zeal... even in the reign of the Sultan an allowance was clandestinely given, so that the puja, or worship, never was entirely stopped, as happened in many less celebrated places.

TIPU WAS HIGHLY superstitious and relied on several forms of divination, including astrology and his own dreams, to make sense of the chaos around him and the constant challenges that life was throwing at him. Even on the last day of his life, he had summoned Brahmin priests and astrologers to conduct japam (chants) and pujas for him, as also to look minutely at his own horoscope for clues on what he should be doing. Melukote Araiyar Sri Rama Sharma narrates an interesting anecdote: ‘Given his predisposition towards superstition, it is widely believed that Tipu was told once by some wise man that he should leave three types of stones (meaning idols) in Mysore unmolested: “Yeddha Kallu (standing stone), Biddha Kallu (fallen stone), Gundu Kallu (round stone).” If he ever mistakenly attempted to desecrate these three, the end of his regime would usher in. The Yeddha Kallu here was the standing idol of Cheluvanarayanaswamy in Melukote, the Biddha Kallu was the supine idol of Ranganathaswamy in Srirangapatna, and the Gundu Kallu was the round Shivalinga of Srikantheshwara Swamy in Nanjanagud. Particularly, the astrologers and Brahmin priests seem to have induced this belief very strongly in Tipu’s mind, along with a kind of manic fear for the very word “Ranga” or “Ranganatha” in his mind. The Chamundeshwari idol too was attempted to be destroyed during Haidar’s time, but the priests got wind of this sinister plan. They hastily and cleverly concealed the original one and had a duplicate one installed, which bore the brunt of the attack. This mutilated idol is still housed in the Chamundeshwari temple in Mysore.’

The fear in his mind for the word ‘Ranga’ seems quite plausible when one sees the plethora of temples in southern Karnataka, all part of erstwhile royal Mysore state, bearing the name of ‘Ranga.’ Several of them are not even shrines of Ranganathaswamy, the lying image of Sri Mahavishnu on the serpent. For instance, in Magadi, a small hamlet near Bangalore, which was the home of the chieftain who built the city and its original mud fort, Kempegowda, there is a temple of ‘Magadi Ranga’ that is believed to have been constructed during Chola times. The principal deity here, however, is a standing Venkateshwara, and behind somewhere is tucked in a small, innocuous idol of a supine Ranganatha. This deity has been named as Beleyo Ranga or the growing Ranga, with the belief that this small idol will grow someday into a large one as we normally see in Ranganatha shrines. The local folklore and tales from the priest confirm that the temple itself was hastily renamed so that it could be saved from the wrath of Tipu or his marauding armies. There seems to have been a standing instruction not to molest any temple that had ‘Ranga’ in its name. We thus have several such temples: Kalyana ‘Ranga’ in Hemagiri (which too is actually the temple of Venkateshwara), Biligiri Ranga atop the B.R. Hills in Chamarajanagara (again a standing image of Ranganathaswamy), Guddada Hole ‘Ranga’ at Navile in Maddur (standing deity) and numerous others. So, it is quite likely that to save the deities and the temples, this innovative method was used by the Hindus of the time to quickly install a Ranganatha idol or rename their deity with a ‘Ranga’ suffix to ensure that they survived the sword of the Sultan.

The superstition instilled against the desecration of the three important shrines in Melukote, Srirangapatna and Nanjangud could also possibly explain why Tipu placated these with gifts, shawls, vessels and elephants.

After the Third Anglo-Mysore War and the manner in which there was largescale internal sabotage, Tipu gave up hope of being able to win over the trust of the Hindus. With his revenues coming down after the treaty signed in 1792, with half his dominions gone, he issued his new commercial regulations that called for a takeover of temple land grants. Temples in Mysore would have thereby lost their source of sustenance and daily worship after this state takeover of their grant lands. But to balance this out and placate the Hindu subjects, it is around this time that we find Tipu’s letters to the Shankaracharya of Sringeri. There does seem to have been a genuine reverence for the Shankaracharya both on the part of Haidar Ali and Tipu Sultan, as evidenced in the letters they had been writing to him. In the shameful episode of the destruction of the Sharada temple by the pindaries in the Maratha army, along with a genuine concern for the Swamiji, there also seems to be realpolitik kicking in where Tipu wanted to capitalize on the situation to score a major point over his bitter foes, the Marathas. That these grants and offers of help were also followed by requests to pray for his victory and long life also show how by then he had come fully under the control of astrologers and others in the wake of the uncertainties of war and the reverses he faced. It was quite ironic that around the time he had confiscated the land grants made to temples and Brahmins, he was also requesting the Shankaracharya to employ the very same community of Brahmins to perform incantations, penances and other rituals for his longevity.

The humiliating defeat in the Third Anglo–Mysore War seems to have been an inflection point in the reign of Tipu Sultan regarding his attitude towards the Hindus of his kingdom, whom he suspected increasingly of conspiring against him. Hence, reducing their participation in government, confiscating the lands and revenues of temples and Brahmins, and differential taxation systems seem to have gained momentum after this period.

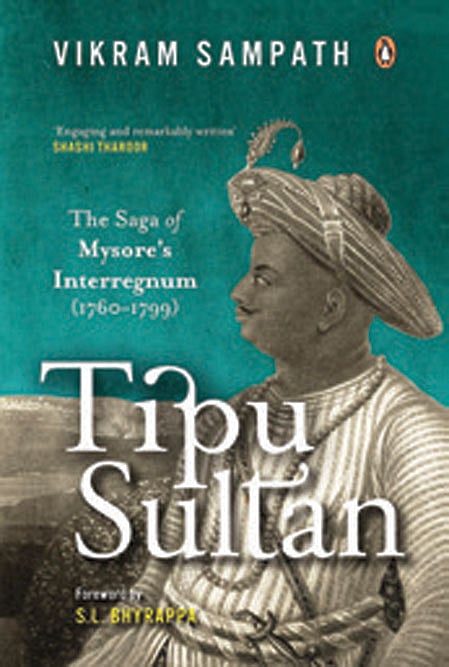

(This is an edited excerpt from Tipu Sultan: The Saga of Mysore’s Interregnum (1760-1799) by Vikram Sampath)