Thresholds of Time and Space

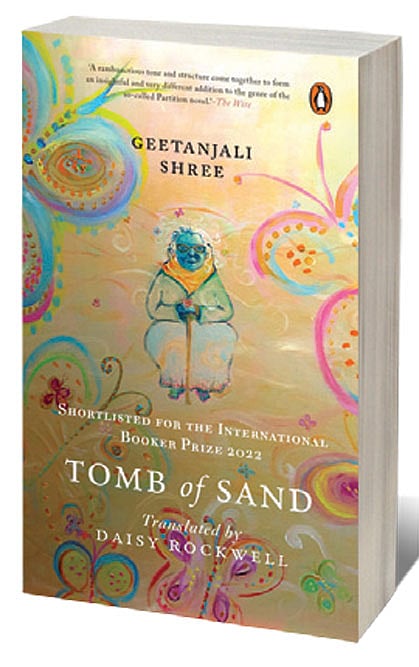

THERE IS JUSTIFIABLY much excitement in the Indian literary community about Geetanjali Shree’s Tomb of Sand being on the shortlist of the International Booker Prize, the first Hindi novel to ever be so. The award celebrates translations of world literatures into English and is a relatively recent offshoot of the Booker, the prestigious prize for works originally written in English. Most of Shree’s works (her novels and short stories in particular) have been translated into a host of languages, some as disparate as Serbian and Korean, and she is rich in awards and recognitions. Here, the translator for Shree’s substantial book (which comes in at about 700-plus pages) is Daisy Rockwell, no stranger to hefty Hindi fictions. This same translation has already won an English Pen Award when it was published last year by Tilted Axis Press and the Indian edition is described by its own blurb as a ‘Partition novel’ with the added attractions of being humorous and exploring the constructs of womanhood and feminism.

My reading of the book led me to a finely delineated and sharply observed story of a middle-class Delhi family—the son is a bureaucrat, his wife a somewhat oppressed daughter-in-law who loves her sons fully and well but is not quite as large-hearted about her husband. The daughter of the house is unconventional and bohemian, choosing to live away from the family and often at odds with her strait-laced brother and his long-suffering wife. But the jewel in the crown of this mostly ordinary family is Amma, the old lady who sinks into a paralysing depression after the death of her husband. Fortunately, Amma is roused from her private grief and persuaded to return to the world of people and things, its many wonders and seductions. It is her adventures and escapades that are the backbone of the novel which swirls through the quotidian as well as the unusual.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Amma disappears from her son’s house for an unspecified period of time and when she returns, she moves in with her daughter, bringing with her entirely new ways of living in the world and experiencing such vagaries and constants as sickness and health, joy and sorrow. Amma has a new best friend, a transgender woman named Rosie, who brings the chaos and cacophony of liminality with her into the hitherto steady, largely unremarkable lives of Amma’s family. Healing potions emerge from her sling bag, a small cottage industry of artefacts made from waste takes shape under her restless fingers and slowly but surely, magic begins to hover in the air.

Other novels by Shree also play with the magically real and the really magic, each verging on the other, each threatening to burst its bounds but not always doing so. Much of her work also situates itself around spaces with fluid boundaries. These limns are often thresholds of time and space, such as doors and windows, dreams and memories, the corporeal and the ethereal, narrative and commentary. Tomb of Sand brings Shree’s fascinations and techniques to the fore—historical persons wander in and out of its pages, there are meta-textual interludes including a pretty extensive one about the choices and processes of translation, there is a mysterious and shadowy third person narrator who appears every now and then and adds a subjective point of view to the story. Rosie seems to have a male doppelganger called Raza—might he be the male body that she has left behind in her transformation? A tiny red-breasted sparrow turns into a fairy and is consumed by what she loves best, a community of crows are briefly a Greek chorus bearing news that cannot be communicated, a younger son is born without the capacity to laugh, an astounding medical phenomenon in Amma’s body turns out to be merely an odd shaped cyst. Where does reality lie in this story, among these characters? Is truth seen or felt or realised? Shree leaves all of those decisions (if they must be made at all), entirely up to the reader.

The last section of the novel does take us to Pakistan and we find ourselves trapped in the horrors of Partition, as the blurb had promised. Amma leads her daughter on a dangerous journey fuelled by the past, a journey led by a fragmented memory that further splinters an already fractured narrative. However, many of the seemingly random threads of the story thus far are tied up, some oddities and mysteries are explained by the terrible tumult that the division of the sub-continent unleashed and the haunting title of the book finally reveals its full meaning. It is in these frenzied pages that Shree makes her most pointed critiques of society and nation, adding yet another dimension to the already layered text.

Rockwell is an able translator of these multiple layers and voices and positions contained within the story. She has clearly enjoyed this challenging project and mentions, in her Translator’s Note, that the novel is actually a love song to Hindi, full of word play and resonances. Shree herself speaks of her great pleasure in “dhwani”, a concept from Sanskrit literary aesthetics, which nurtures suggestion and encourages a wealth of allusion in both sound and sense. Rockwell also revels in these linguistic games and is frank about the impossibility of rendering them all into English with integrity. And I do like her final word of advice to readers who might find the English translation falling short, for these and perhaps other reasons. Rockwell says that they might be better off reading the novel in Hindi and adds the cheeky suggestion that they use the English translation as a trot. Touche, Ms Rockwell, touche!

Readers make extraordinary demands on translations, expecting levels of fidelity across languages and cultures that are impossible to achieve if the literary work is to remain readable and hold within it the wonders and pleasures of the original. In many ways, a translation is a new work (albeit a dependent one) that must both compel and thrill a new audience. No translator worth their salt would use that possibility of newness as a license for liberty with words, phrases, idioms and similes, for a translator’s first and inviolable contract is with the text itself. It is at this point of contact, this delicate membrane that vibrates between languages, that the translator can listen, can hear dhwani. It is our job to find the suggestions and allusions that make the new work resonate as fully as possible with its original. In music, resonance is when an object vibrates at the same rate as the sound waves from another object. In literature, we find dhwani when a translation’s vibration is synchronous with the language and culture of its original. Judges for the International Booker Prize should, ideally, have good ears, as musicians might. For while they read English translations from all over the world that have been published in the UK, their job, really, is to listen for resonance.