The Young Gandhi

The daunting task before any historian is to rescue Gandhi from the unthinking admiration of posterity. Despite a slew of works that explore his ambivalence over the violence of caste, his experiments with sexuality and his authoritarian style of politics, the idea of Gandhi as a saint who strayed into politics dies hard. Added to this is the tendency to read his life backwards from his status as a mahatma: the years in England and South Africa are rendered as mere preludes to the making of this complex figure. There are several obvious facts that are forgotten in hagiographic tellings. First, that Gandhi, born in 1869, was, in terms of his conservatism in politics, a 19th rather than a 20th century figure. He had many of the political and cultural obsessions of a late Victorian liberal, not the least of which was a deep suspicion towards the unregulated entry of the masses into politics. Second, the popular perception of Gandhi as a Bania, with the attendant stereotypes of bargain and compromise, occludes his patrician origins in a family of chief ministers to princely states in Gujarat. If we keep these in mind, his preference for social order and hierarchy and his faith in the principles if not behaviour of the British Empire can be seen as integral to his politics.

Leela Gandhi's textured work on Gandhi's early life in London in the context of an anti-imperial sub-culture allowed us to understand what had appeared merely to be youthful and eccentric engagements with vegetarianism, animal rights and pacifism. His life in South Africa has been well served by a number of books, but two recent works by Joseph Lelyveld and Ramachandra Guha have taken this phase on as central to the making of Gandhi. And two more different books cannot have been written. Lelyveld, as a reporter for The New York Times, had written a classic work on South Africa under apartheid and was keenly concerned with questions of race and inequality. His biography of Gandhi's years in South Africa brought this lens to bear in revealing Gandhi's ambivalence towards race, which led to a curious politics that excluded Africans from his considerations as a force for change. Guha's account, which is relatively anodyne and consistent with the popular view of Gandhi as a mahatma, makes claims for Gandhi's radicalisation of South African politics in the early 20th century while circumventing the issue of race. Given the current political atmosphere in India where Ambedkar is being resurrected as a radical thinker of equality for modern India, Gandhi's insistence on a proper politics of social order is presented as reactionary. And South Africa, where he forged an Indian politics to the exclusion of Africans, appears to prefigure his later conservatism on matters of caste inequality.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Desai and Vahed address centrally the question whether Gandhi was a racist; an exigent question for contemporary South Africa where he has 'been reinvented as an icon of non-racialism'. They make a convincing argument that Gandhi's 'political imagination was limited to equality within Empire' and framed by the idea of imperial citizenship. The 1858 Proclamation of Queen Victoria after the 1857 uprising guaranteed all subjects of the Empire equal rights and guarantees against discrimination. This idea was what governed Gandhi's engagement with the British in South Africa—that as Indians and subjects of the Empire, they were entitled to rights of settlement, movement and property. However, a crucial component of this argument was the distinction that he made between Indians and Black African 'kaffirs' in contemporary parlance. Gandhian politics constantly resisted the attempts by the British 'to degrade us to the level of the raw kaffir whose occupation is hunting, and whose sole ambition is to collect a certain number of cattle to buy a wife with and then, to pass his life in indolence and nakedness'. There are many ways in which such opinions can be glossed over: Gandhi was a man of his time; this argument was made within a discourse of imperial citizenship, differentiating Indians from Africans, and so on. But there is no mistaking the common prejudice and stereotype that underlies Gandhi's prose as much as the desire to align his views with that of White rulers.

Gandhi's arguments against the creeping discrimination towards Indians as South Africa moved towards becoming a republic under Boer control were a last ditch stand summoning the idea of imperial citizenship and fair play. But by 1910, it was clear that a colour line had been drawn across the world, and White rule was not going to give in to assertions of equality by coloured people from Canada to Australia and certainly within the British Empire. Nevertheless, Gandhi continued to assert that the British Empire was 'not founded on material but on spiritual foundations' and that there was something 'subtle and fine' in the ideals of the British Constitution. All of this was maintained against the background of the construction of the new South African state built on the dispossession of Africans and the introduction of a migrant labour system that produced profits from mines. Gandhi had little to say on this continuing devastation of the African countryside and community life, and his participation as stretcher bearer in the Bambhatha Rebellion in which Zulus were savagely put down makes clear where his loyalty and politics lay. In response to the White League's agitation against Indian immigration, Gandhi rushed to reassure public sentiment that he believed that 'the white race in South Africa should be the predominating race'. And in an anticipation of his advice to Jews in Europe to practice passive resistance against Hitler, he stated that had Bambhatha 'simply taken up passive resistance… much bloodshed could have been avoided'.

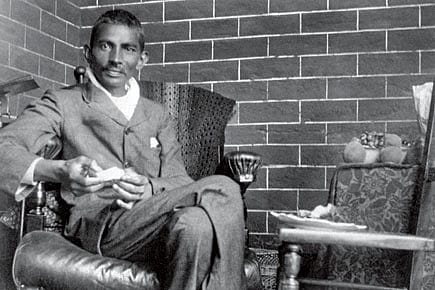

Vahed and Desai are meticulous and relentless in their piling up of evidence that Gandhi not only saw Africans through the civilising eyes of Europeans, but also that he saw himself as a loyal subject of the Empire till the point that he left South Africa. We must study the South African Gandhi as a distinct avatar. It is not without significance that when Gandhi travelled to England in 1909 to lobby against a bill that would deny Indians and Blacks political rights, he was dressed in 'the conventional dress of a pre-war English gentleman—a silk hat, well-cut morning coat, smart shoes and socks', a far cry from the 'half naked fakir' who was to become Churchill's bugbear. The fight was for the 'right of cultured Indians to enter the Transvaal in common with the Europeans'. The arguments that Gandhi was to make in Hind Swaraj about the glories of Indian civilisation alongside his rejection of the European one were part of the discourse of parity with Europeans and elevation above Africans.

The campaign and rebellions of 1913 which began in South Africa's coal mines were to extend beyond Gandhi's control (with his insisting as he would in India that strikers 'had no quarrel with mine owners') to its plantations, and iron, candle, soap and glue factories and cement and pottery works. Here too, we see a prefiguration of what would happen in India where 'Gandhian' Satyagrahas would exceed the conservatism of the leader and assume a radicalism of their own, which Gandhi would rush to disavow. The politics of imperial citizenship, the exclusive focus on Indians over Africans, and a continuing belief in British justice characterised his South African years. It helped establish Gandhi as the sole spokesman for Indians, but did little to alleviate the condition of the local population.

(Dilip Menon holds the Mellon Chair in Indian Studies, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg)