The Wrong Girl

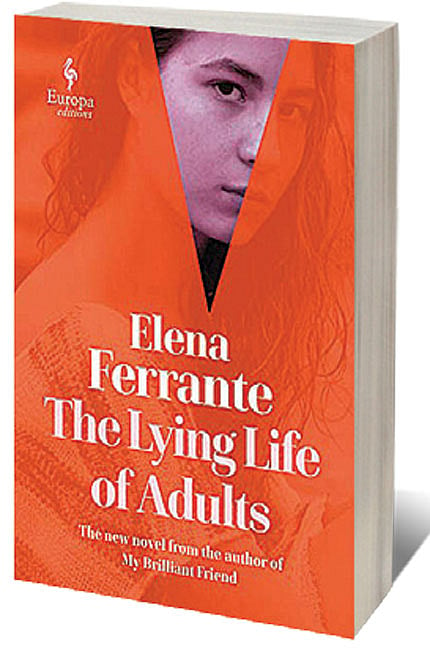

ELENA FERRANTE HAS a new novel—for those of us who fell under her spell a few years ago, nothing could light up our reading lives more or better, especially in these dark days of the insidious pandemic. The Lying Life of Adults is about 300 pages long, enough for a satisfactorily deep dive but without the dangers of the complete loss of orientation which overcame us when we read her Neapolitan quartet. Lying Life is also situated in Naples and also concerns a young girl growing up, struggling with herself and her family, looking for love and yearning for a larger world which will simultaneously liberate her and give her life meaning. This time, though, Ferrante’s canvas is smaller, the narrative arc of her characters is shorter and the reader does not exit the book drained of all the emotions they had used up in the course of devouring either the Neapolitan narrative or The Days of Abandonment. The reader can still breathe, can still rise from their reading position and believe that the world has not actually stopped rotating on its accustomed axis.

In Lying Life Giovanna is an only child whose parents are teachers and intellectuals. This close-knit nuclear family inhabits a genteel middle-class life in the upper, posh part of Naples, far from the teeming ghettos and the ‘industrial zone’ where lives are lived in precarious poverty and families are larger and more complex in their interactions. Giovanna’s parents are friends with another equally genteel couple who have two daughters, Angela and Ida. The older couples form a companionable unit of shared meals and animated conversations while their trio of daughters exist in a tight friendship of childhood secrets, tears and laughter. Giovanna and her father, Andrea, have the sweet relationship that fathers and only daughters can often develop, one that nurtures each and allows both to feel especially beloved. As much as she adores her father, Giovanna knows little of his family, though she does know that he had spent his childhood in those narrow alleys lined with decaying buildings and littered with broken people that lie at the bottom edge of the city.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

One day, Andrea says to his wife that his daughter is ugly and that she is developing ‘the face of Vittoria’. Giovanna overhears her father’s comment and is shattered. She knows that the remark is not only about her looks (as if that were not devastating enough for a 12-year-old girl) but is also about her nature, it is a judgement upon her soul. Vittoria is Andrea’s sister, the root of his estrangement from his family—a woman who is rarely mentioned by Andrea and his wife—but when she is, she is spoken of with bitterness and disdain. Giovanna decides that she must know more about her aunt whom she has only heard of as a physically and emotionally unpleasant woman, someone who is disruptive and corrupt in some profound way.

And so begins a Ferrante narrative that we recognise. Giovanna seeks out her aunt, she learns about the great love affair of Vittoria’s life which was with a married man, she plunges into the lanes that form the underbelly of Naples, she meets other members of her father’s family, she becomes friends with the children of her aunt’s lover, she learns why Vittoria hates Andrea. The revelations are many, they are hurtful and confusing, mainly because Vittoria is rough, crude, a bully. But she has a powerful honesty, a pull towards the truth about the world and about human relationships as she sees them. Is she truly ugly in body and soul, as her brother had said she was? It’s hard to tell. Vittoria is charismatic and compelling, bending the people around her to her will. Giovanna finds her alternately beautiful and repulsive and she sets out to decipher the enigma of this woman who life has, Vittoria claims, been blighted by her brother’s vicious and vengeful betrayal. Slowly, Giovanna stops hiding her relationship with her aunt and even though her parents are not pleased, they do not prevent her from exploring the new world that she has entered.

As Giovanna is drawn deeper and deeper into Vittoria’s shambolic life, a talismanic bracelet appears which will link the upper and lower parts of the city, generations of women across social class, friends, lovers and rivals. Lives will change, relationships will form, others will break, anger and jealousy will be unleashed, secrets will be revealed, love and sex will be confused, one for the other. As we stand and watch, we know that no one we encounter in this helter-skelter will ever be the same again.

Almost as a side story, Giovanna sees her mother flirting with her father’s best friend and soon, her parent’s placid, easy going marriage has broken up. Not, however, because of her mother but because her father has brought into the open his long-time relationship with his best friend’s wife. Giovanna finds that her own childhood companions, Angela and Ida, are now practically her step-siblings. She is angry with her mother and she begins to see the smug, bourgeois hypocrisies that have framed her parent’s lives, as Vittoria had promised she would.

The compelling thread through all of this is Giovanna’s determination to debase herself in all kinds of ways—she stops doing well at school, she changes her wardrobe and her make-up, she becomes sulky and withdrawn in her mother’s home, she seeks more and more daring sexual encounters with young men she doesn’t like. We are expected to understand this not as a consequence of her parent’s separation, but as the devastating effect of her father’s comment about her being ugly. Vittoria is always hovering, a malefic presence even when Giovanna decides to stop seeing her. But even as Giovanna’s self-hatred pushes her towards greater personal degradation, she begins to think about god and religion, drawn into that conundrum of human existence by a charismatic young preacher who is engaged to her new friend, Vittoria’s lover’s daughter.

The reader will find all the elements of a true-blue Ferrante novel in Lying Life. But something goes wrong. This novel is a pale shadow of what it could have been, or rather, a pale shadow of what we have come to expect from Ferrante. Other disappointed reviewers have laid the blame for the failure of Lying Life at the door of Giovanna’s relationship with her father, claiming that exploring what holds fathers and daughters together and what drives them apart have never been Ferrante’s forte. I disagree that the story is about Giovanna and her father. I think this novel is also about girls learning to see themselves in each other, of women knowing that a picture of themselves is complete only if it includes the women around them, both the women they love and those that they hate. Perhaps the problem with Lying Life is that we are too much in thrall of the Neapolitan quartet, perhaps Ferrante herself is still under that spell. Vittoria is a monstrous caricature of Lila, Andrea is a watered-down version of Nino, Giovanna herself is a twisted Lena. There is not much here that is new. That which is old and beautiful, what is familiar, what we recognise and thirst for, seems tired and worn.

It is a sad day when your favourite writer does not present you with yet another shining object to treasure, an object so special that it glows more brightly when you share it with others. But we are grown women now, we have more in common with Lila and Lenu in terms of experience and spirit than we do with young Giovanna. We know that even our most brilliant friend will have times when they seem to have dimmed. But it is we who have to keep the faith. It is we who must be patient as we wait for their light to return. We know that it will. For our friend is brilliant, after all.